Their Finest Hour

A Scout’s duty is to be useful and to help others

— The Third Scout Law

When World War Two broke out, young Derrick Belfall, like thousands of Boy Scouts up and down the land, offered his services as a messenger for air raid wardens. One night at the height of the Blitz he was entrusted with an urgent message from his ARP post to the control room. Because the phone lines had been destroyed, he took it in person. As he made his painful way back amid the crump of falling bombs, he passed a house which had been hit by an incendiary. Collecting a stirrup pump, he single-handedly brought the fire under control. Next he entered a second burning house to rescue an injured baby. Then there was another message for the control room and, although it was long after the end of his shift, he volunteered to take it. As he returned, a bomb exploded close by. Picked up badly wounded from the street, he was carried to hospital where he was heard to mutter, “Messenger Belfall reporting. I’ve delivered my message.” Then he died. He was fourteen.

That story is true. So too, at least in outline, is every wartime deed by a Boy Scout that is recounted in these pages.

Throughout twelve nightmare months in 1940-41 Britain, backed only by its distant Commonwealth and Empire, stood alone against the German onslaught, until at last it was joined by the Soviet Union and China and finally by the United States. By delaying Hitler’s plans, it had won for the world a year of precious time. In the process the nation was bludgeoned almost to its knees; but, thanks to the RAF and the staying power of the people, it never quite succumbed. The cost, however, was huge. In Britain, in the course of the war, 67,093 civilians were killed and the infrastructure was battered sometimes out of recognition.

In this tale, the history is real, as is the setting — the East End of London, which bore the worst brunt of the air raids and for the longest period. A not dissimilar picture, if over shorter time-spans, could be drawn of many another city in Britain.

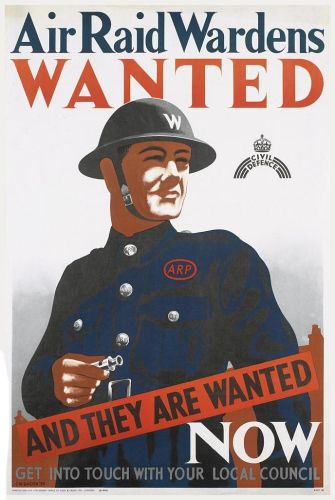

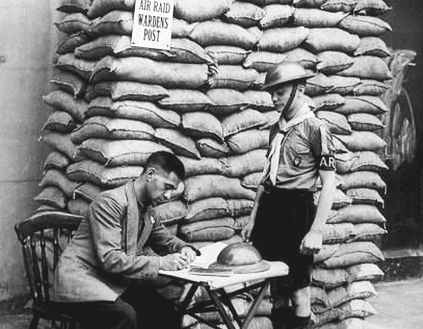

Alongside the people at large, the heroes of the Home Front were the Civil Defence Service — the Air Raid Precaution wardens, the fire watchers and fire fighters, the first aid parties and stretcher bearers and rescue corps, every man and every woman a volunteer. Helping them out, even in the thickest of the action, was a small army of Boy Scouts, of whom no fewer than 194, like Derrick Belfall, gave their lives.

Here, seventy years on and inspired by the VE Day commemorations of 2015, is a small tribute to what those Scouts did. Its backcloth is a tapestry of real-life scenes drawn from a wartime perspective, into whose fabric are embroidered my own fictional characters. The essence of it, never forget, is true. Archive images, moreover, can be so powerful that it seems almost a crime not to include a selection. I am indebted to Hilary, Pryderi, Ben, Jerry and Ken for their comments, and to Jonathan for standing beside me, if unrecognised, throughout the war.

4 July 2015

1. Lead-up

“This morning the British ambassador in Berlin handed the German government a final note, stating that unless we heard from them by 11 o’clock that they were prepared at once to withdraw their troops from Poland, a state of war would exist between us. I have to tell you now that no such undertaking has been received, and that consequently this country is at war with Germany.”

The three of us — three, not four, now that Brenda was gone — were listening to the Prime Minister’s broadcast. Dad was swearing under his breath. Mum had covered her eyes in despair. And my mind was torn. This news was exciting. For a thirteen-year-old it was bound to be exciting, and boys like excitement. Yet I understood something of what was happening in the big wide world and of what was at stake. For the past year Dad had talked of little else. Over and over again he had told us that war would be terrible, and now he was swearing. I knew what his swear-words meant — we might be a respectable family, but you can’t grow up in Stepney without meeting ripe language. What drove home the horror of the news was the fact that he was swearing at all. I had never heard him swear before.

The place was our sitting room. The date was 3 September 1939. The time was quarter past eleven in the morning. And at twenty past eleven the siren sounded its banshee wail. We had heard it before in practice. Was this the real thing already?

We were far from unprepared. Everybody knew that war was creeping inexorably closer. Dad had told us his childhood memories of the Great War and how bombs had fallen on London, at first chucked by hand out of Zeppelins but later — and much more efficiently — dropped from planes. But that was twenty-odd years ago. Since then, he pointed out, the technology of planes and bombs had raced ahead. Next time would be far worse. Newsreels of Barcelona and Guernica in the Spanish Civil War had shown us the hideous destruction that aerial attack could these days unleash upon the innocent.

The Government had preparations in hand. The previous September, when I was twelve, the whole population had been issued with gas masks, and kids were taught at school how to put them on. The boys of course, being boys, instantly discovered that by breathing out hard you could get them to utter wondrous farting noises and thereby drive the teachers to distraction. The trouble was that the things stank of rubber, the eye-piece steamed up, they looked ridiculous, and they were wretchedly uncomfortable to wear; still, as Dad pointed out, you never knew what the Germans might try, and better ridiculous and uncomfortable than dead.

Then Neville Chamberlain had returned from the Munich conference waving a piece of paper and proclaiming ‘peace for our time’. Many people, Dad among them, saw that as hollow. This agreement the Prime Minister was so proud of had given Germany the go-ahead to annexe the Sudetenland. Wasn’t that a mere prelude to further aggression?

And thus, long before we were actually at war, the war effort got under way. Scouting was deep in my bones, and as a member of the 11th Stepney (St Dunstan’s) Troop I began to play my little part. Scouting was also deep in the bones of Stepney. There were plenty of other troops in the borough, several of them attached to synagogues, as well as one of Sea Scouts. Ours met in the parish room adjoining St Dunstan’s church, a handy quarter mile from home. A handy quarter mile the other way was Roland House, which was not only the headquarters of all the East London Scouts but a base for scoutmasters and a hostel for visitors.

At this stage our contribution to the war effort was the sort of thing that Scouts are traditionally good at. We filled sandbags by the thousand. We made camouflage nets. We salvaged waste paper and bottles in prodigious quantities. We collected clothing for the refugees who were flocking in from Europe and for those who, should the worst come to the worst, might be bombed out of their homes. We set up Christmas parties for the poorer kids. We raised money by bob-a-job and jumble sales and fetes — one single troop in west London, I heard years later, generated enough during the war to pay for no fewer than eleven Spitfires.

Our scoutmaster was a wonderfully human character, almost universally referred to as Fred although to his face we Scouts had to call him Mr Bruford. A senior clerk at the London Docks, he was a close friend of my Dad’s. Both of them, though great fun, were serious-minded men, desperately worried about the way the world was heading and dedicated to doing what they could for the community and the country. His wife having died years before, Fred and his son Doug lived in a small flat near Roland House in Stepney Green. And if Fred was Dad’s best friend, Doug was mine.

Which brings us to us. My name is Charlie Johnson, and we lived in a little Georgian house on the south side of Arbour Square. Dad was a colleague of Fred’s at London Docks; but Mum had no job beyond helping as a volunteer at Dr Barnardo’s Home and looking after the rest of us, which meant Dad and me and Brenda who at that time was nine. We were very far from rich, but we were not poor. Indeed by Stepney standards we were rolling.

Doug and I were well aware of that. We could see it with our own eyes, for we knew our patch inside out. Our regular pastime — you might call it our hobby — was to bike around it from Tower Bridge to Limehouse Cut, from Wapping High Street to Mile End Road. Its geography had become as familiar to us as the back of our hands, down to the last short-cut alleyway and the smallest cul de sac.

The borough of Stepney lies immediately east of the City of London; indeed the Tower of London falls just inside its boundary. It is the heart of the East End. It is roughly oblong in shape, little more than two miles long and a mile wide, but its population before the war was nearly a quarter of a million. This meant it was densely packed, not only with houses but with many small garment workshops. Apart from the occasional churchyard and three docks — St Katherine’s, London and Regent’s Canal — there were virtually no open spaces at all. Away from a few little oases like our Arbour Square and Stepney Green, this was a realm of desperate poverty and downright slums. The east-west strip just north of the Thames, around Commercial Road and Cable Street, was the worst: a run-down area of seedy businesses, dark passages and dilapidated tenements, cheap lodgings and dubious pubs; of brothels and opium dens too, we heard, though they did not advertise themselves.

Not only did we know its geography, but we knew its people, or a typical slice of them. Neither of us was a true native. Our parents being respectable outsiders, by background we were a far cry from the local norm. While we had been born in Stepney, that hardly made us Cockneys. Yet we were bilingual, able to switch at the drop of a hat from the wishy-washy suburban accent we used at home to faultless Cockney picked up from school. And as we biked endlessly around we became quite well-known figures on the streets. We would be greeted as we passed with a ‘top o’ the morning’ or a ‘shalom’ or a simple ‘wotcher,’ for Stepney was an ethnic jumble. Less than half the people, probably, were real home-grown Cockneys. The rest were immigrants who, arriving at the docks, had got no further; or sailors who had jumped ship or been paid off; or those who had turned up hoping for work in the garment trade. Plenty were Jewish, nearly as many were Irish, quite a number Chinese. A few were Muslims or turbaned Sikhs or even black.

In the March of 1939, with the international prospect growing ever gloomier, Dad called a family conference. Everyone, he told us children, had a duty to their country. He said it not dramatically but as a simple fact. We knew it already, for the message had been fed to us almost with our mother’s milk. And if the war proved long-lasting, Dad said, he would sooner or later be called up to fight. His news now was that he was giving up his job at the Docks and volunteering, not as a soldier but as a full-time air raid warden. His hours would be longer than before — 72 hours a week — and his pay less, but he felt it his duty. Most wardens were part-time, but it was already clear, he said, that Stepney was going to be desperately short of them. Mum felt it her duty too, and was enrolling as a part-time warden, expected to work up to 48 hours a month.

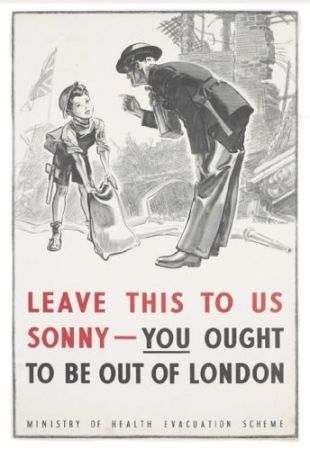

“That means, Brenda,” Dad went on, “that we won’t have nearly so much time to give to you. And if war does come, we’re going to be bombed. So the Government’s arranging to move all children of school age out of harm’s way, which we think is right. But there’s no telling where you’d be sent, only that you’d be housed with strangers who you might not like. But we’re lucky, because we’ve got Auntie Sybil in Oxfordshire. You do like her, don’t you? So we’ve asked if she’ll look after you, and she’s said yes. How do you feel about that?”

We knew Auntie Sybil fairly well. We had stayed with her for holidays. Brenda loved the countryside. But she loved us too, and her first question was, “How long for?”

“I’m afraid we’ve no idea, darling,” said Mum. “But no longer than it has to be. And we’ll come down and see you as often as we can.”

“All right,” said Brenda bravely. “But isn’t Charlie going?”

I was evidently not being banished willy-nilly as well. That was a relief. Auntie was Mum’s sister and was all right, up to a point. But unlike Mum and Dad who treated me as older than I really was, she seemed to think I was Brenda’s age, or even less.

“Well, that’s the next question,” said Dad. “Charlie, you’re on the borderline. You’re nearly thirteen, and in a year you’ll be leaving school. If schools are evacuated, as they very well may be, there won’t be any here for you to go to. So there are two options. One is to go with Brenda, though we’re reluctant to burden Sybil with another visitor. The other is to stay with us and make yourself useful. There’ll be plenty of work here for responsible youngsters, taking some of the load off the adults — the sort of thing that Scouts are trained to do. Messengers will be needed, for example, to run errands for wardens or the firemen. It could be hard work. It could even be dangerous. But it would be a vital contribution. The choice is yours. Think very carefully about it.”

“I don’t need to think, Dad. I’ll stay. I’ll chew it over with Doug. But I’ll definitely stay.”

I saw approval on Dad’s face, and worried pleasure on Mum’s.

As soon as possible I chewed it over with Doug. He was the same age as me to within a fortnight. We had been best friends as far back as we could remember. We thought alike. We were the sons of our parents — well-principled, dare I say it, as boys go, and reasonably well-informed — if in some departments we were still woefully innocent. Fred had given Doug much the same choice as Dad had given me, and as expected his answer was the same. He would also stay. We bumped shoulders, which was our sign of solidarity.

Just as families were facing up to reorganisation, so too were the Scouts. Fred began to move our troop away from passive collecting for the war effort to a more active role; to set us, as he said, on a war footing. Most of the younger members were resigned to being evacuated, but most of the older ones were staying put. Of these, some were not allowed by their parents to take on potentially dangerous jobs. Fine, Fred told them. We’re a team. Don’t feel inferior if you aren’t in the front line. Work behind the scenes is just as vital.

As another contribution to the war effort, these Scouts started a garden on a piece of waste ground. As head gardener a boy was appointed who claimed some knowledge of the art, and he deployed his forces. They borrowed tools from parents. They planted and tended. Their labour was hard, but often in the evening you might see a minuscule pair of Cubs weeding, or a larger Scout wielding a fork. After some months their efforts looked like paying off. Sadly, this being Stepney, opportunists had been watching and waiting, and the burgeoning cabbages and potatoes vanished overnight.

For those of us who did have parental approval, Fred suggested we consider enlisting as part-time volunteers with one of the branches of Civil Defence such as the AFS — the Auxiliary Fire Service — or the ARP — Air Raid Precautions. So Doug and I presented ourselves at the Council Offices and offered our services as ARP messengers.

“Have you got bikes?” asked the clerk.

“Yes.”

“Good. You’d get an allowance for wear and tear, and free batteries for the lamps. How old are you?”

“Thirteen,” which by now we were.

“Oh. The minimum age is supposed to be sixteen. Do you have any special qualifications?”

“Well, Scout badges. Fireman, first aid, cycling, pathfinder.”

“Ah, just what we want! Right, boys, you’re in, even if you’re officially too young. We’re that short.”

“Why,” I asked Dad when I got home, “are they so short of wardens and messengers? I’d have thought people would jump at it.”

“It’s complicated, Charlie.” He sat back from his form-filling to consider. “This is the East End, remember. People in Stepney aren’t as regimented and cooperative as they are in most other places. There’s a long history of unrest here. Thirty years ago there was the famous Siege of Sidney Street when some anarchists holed up in a house and murdered several policemen, and were only put down by the military. And do you remember the Battle of Cable Street in ’36 when Oswald Mosley and his blackshirts tried to parade through the borough? They were confronted by hordes of opponents organised by the dockers and Communists and Jews, all shouting ‘They shall not pass!’ It’s claimed there were a hundred thousand of them, and the poor police got caught in the middle. But the fascists didn’t pass.”

I did remember that. Back then I had been ten. Total chaos, and a lot of injuries.

“Well, one result was that Phil Piratin was elected to the Council, the first Communist councillor we’ve had. And one of our troubles here … look keep this to yourself, though you can tell Doug because Fred knows it as well as I do … one of our troubles is the in-fighting on the Council between Labour and Communists. Most of the councillors are corrupt and out to line their own nests. All of them are inefficient. Take Morry Davis, who’s the local Labour leader. He’s a positive dictator. If he doesn’t like what the Government tells him to do, he doesn’t do it, or he drags his heels for as long as he can. And that’s what’s happening now. Civil Defence is the responsibility of individual boroughs, and every other London borough has appointed its Town Clerk as ARP Controller. That’s fine: Town Clerks are professionals and likely to be efficient. But here in Stepney the mighty Morry Davis, who’s only an amateur politician, has got himself appointed Controller, and finding wardens is low down his personal list of priorities.” He sighed. “Local politics are a minefield, Charlie. Steer clear of them. That’s my advice.

“And the final factor is that East Enders are fiercely independent types. During the depression they got utterly fed up with the Government for doing so little to help them. In return, they’re not exactly jumping to help the Government now. They aren’t bad people, but they’re reluctant to sign forms that commit them to anything. So they’re not offering themselves as wardens. Or not nearly enough.”

As the summer wore on, we new messengers were issued with ARP armbands and black tin hats with an M painted on, and in addition to Scout activities we were given some basic Civil Defence training. We were taught about first aid and about stirrup pumps, most of which we already knew from our Scout badges. We were taught the much more difficult skill of handling a full-blown fireman’s hose. We were taught something about poison gases and gas detectors.

Then school finished. For me, I thought, it was over for good.

On 9 August there was a trial blackout, and any householder who allowed a glimmer of light to escape was blasted by the wardens. Vehicles had to have their headlights hooded. If there were no moon or stars, it really was dark. You tripped over kerbs. You bumped into people and apologised to them. You bumped into lamp posts and apologised to them too. The risk increased of being knocked down by a car. The Government’s advice was to wear light-coloured clothes and leave your white shirt tails hanging out. For the same reason all spare Scouts were put to painting white stripes on kerbs and lamp posts and the like, and to helping householders who were having trouble with their blackout curtains. For protection, eight thousand Anderson shelters were delivered to the borough, but the Council did not see fit to advertise them and the take-up was small. Adequate shelters were something it took us a long time to acquire.

Come an air raid, rescue would be coordinated from the ARP Control Centre which was set up in St George’s Town Hall in Cable Street, the grand building where Council meetings were held.

“Why not at the Council Offices?” I asked Dad.

“Think.”

I thought, and the penny dropped. The offices were on Wapping Island at London Docks.

“Oh, I see. The only way to get to them is over those two bridges.”

“That’s right. Which might be hit by a bomb. And one of those bridges is of wood.”

Searchlights and ack-ack guns were installed in the few open spaces — including Arbour Square almost outside our windows — and lorry-mounted winches were parked in the wider streets for launching barrage balloons, or blimps as we called them. On 24 August all Civil Defence workers were put on alert. The time was drawing near. We still hoped for the best, but hope was fading fast. Mum took Brenda by train to Auntie Sybil in Oxfordshire and, with tears but not too many, left her there.

On 1 September Germany invaded Poland. That was the final straw. The blackout began, enforced by law, and so did evacuation of the children. In many cases whole schools went, lock stock and barrel, complete with teachers. The Scouts who were staying behind helped the police to marshal them onto buses and trains: endless phalanxes of youngsters, each with their gas mask case around their neck and a large label tied to their clothes as if they were a piece of luggage. They were heading for umpteen supposedly safe destinations around the realm, but none of them knew where: not the parents, nor usually the teachers, and certainly not the children. If many shed bitter tears, some were in high excitement — weren’t they going on holiday? One little boy was spotted carrying a bucket and spade — didn’t holiday mean the seaside?

Over three days, not far short of a million kids were moved out, and the organisation at the London end was impeccable. It was otherwise, we heard, at the reception end. But at least Brenda was in good hands.

And so, on the morning of 3 September, came the tired voice of the Prime Minister on the wireless, telling us that what we had dreaded was now a reality. The siren’s alert which followed proved to be not only a false alarm but a severe anticlimax. The Government issued a stream of directives — rationing petrol, for instance, issuing everyone with identity cards, and authorising a general call-up without yet putting it into effect. A little naval activity was reported. But otherwise the Prime Minister twiddled his thumbs and waited for something to happen. Apart from the restrictions, it did not feel like a war. The Bore War, people punningly called it, or the Funny War; which I suppose is why it came to be known more officially as the Phoney War.

ARP training continued, though without the earlier sense of urgency. Wardens and messengers went on duty, but beyond honing their preparations they had little to do. The ARP was organised into sectors. Doug and I were not allocated to Dad’s sector, which was centred on St George’s by the Town Hall. Ours, under the less than grand title of ARP Post D1, was centred on St Dunstan’s, where a heavily-sandbagged building had been put up in the recreation ground beside the churchyard. We messengers, in theory, worked two six-hour shifts a week, alternating between day and night. Many of us were Scouts from our own troop, some even younger than us, and there were a few girls too. For much of our unproductive time we talked, or read comics, or, like the Prime Minister, simply twiddled our thumbs.

By Christmas, with all this inactivity, most of the evacuees had trickled back home, although Brenda was kept in Oxfordshire. Mum and Dad had been to see her more than once. She was happy, and they felt we were in a waiting game which might end at any moment. In January my school reopened and reluctantly I returned to it. Restrictions, however, continued. Bacon and butter and sugar were put on the ration, followed by more and more foodstuffs. Everyone was issued with ration books.

It was only in April 1940 that the Phoney War came to a tentative end, and in May to an abrupt one. First Germany overran Denmark and Norway. Then, two days after I turned fourteen, it invaded the Netherlands and Belgium and France. On the very same day Chamberlain, having lost the nation’s confidence, resigned and was replaced as Prime Minister by Winston Churchill; and a very good thing too. The British Expeditionary Force, which for months had been in place along the northern frontier of France without having to fire a shot, was outflanked by the Germans, deserted by the Belgians, and rolled back to the Channel. A fair part of its manpower, but none of its equipment, was evacuated from Dunkirk in an emergency rescue, a miracle wrapped in a disaster, which will surely never be forgotten.

Fred, who always liked to keep us up to date, invited a couple of Stepney Sea Scouts to tell us their experiences of that event. Their troop had its own 45-foot boat on the Thames which, like hundreds of other small ships, was summoned to Dunkirk, manned by no more than the scoutmaster and these two boys and a naval rating. For several days, under heavy German fire, they ferried soldiers from the beach to destroyers offshore, and they were lucky to return unscathed. We were envious, in a way; but their first-hand account of the dangers, and of the injuries of those they rescued, and of the sheer horror of conflict, set butterflies at work in our stomachs.

If that sort of thing came my way, as it very well might, how would I react? I simply did not know. Never had I been truly afraid. Never had I had to confront a real emergency. Nor had Doug. The make-believe blood behind our Scouts’ first aid badges was a useful introduction, but we realised now that it was a pale shadow of the reality. We could only wait and see, and it looked as if there would not be long to wait.

Churchill, meanwhile, was thundering defiance.

“We shall go on to the end. We shall fight in France, we shall fight on the seas and oceans, we shall fight with growing confidence and growing strength in the air, we shall defend our island, whatever the cost may be. We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender.”

The story went the rounds, whether true or not, that afterwards he added in private, “And we shall fight with the butt ends of broken beer bottles, because that’s bloody well all we've got.”

Bad moved to worse. Italy joined the Axis. The Nazis completed their occupation of northern and western France, leaving the rest in the hands of the Vichy government which was under their thumb. Britain now stood alone. Hitler would inevitably turn next on us. Invasion seemed imminent. Dad had a serious word with me.

“Charlie, you know how close the Germans are now?”

“Well, they’re in France.”

“Yes, but how close in miles?”

I shook my head. Geography, apart from the geography of Stepney, was not my strongest point. He took out the atlas.

“We’re in London, here. They’re in Calais, there. That’s about eighty miles. If we were in Dover, here, they’d be twenty miles away. From Calais you can see the white cliffs of Dover, easily. The only barrier now is the Channel. So the danger’s much worse than it was. Do you still want to stay?”

The butterflies were fluttering again. I eyed the map. The length of Kent and the Straits of Dover, eighty miles, not very far at all. But I knew how I had to answer. Mum and Dad would never abandon me, so how could I abandon them?

“I still want to stay.”

“Good lad.”

But a new exodus from London began. This time it was nothing like so large, only about a hundred thousand kids. Not enough left from my school for it to close down again, and I stayed there until July, when I really did leave it for good.

In the reverse direction, others came in; out of the frying pan, one might think, into the fire. With the fall of France, large numbers of children were evacuated from the Channel Islands which, being militarily indefensible, were the only part of British soil ever to be occupied by the Nazis. A month or so later another influx — they called themselves the Rock Scorpions — arrived from Gibraltar. Some of both groups were billeted in the borough as a further addition to the ethnic mix, and the 11th Stepney Troop gained a few recruits whose English might be shaky at best.

Twenty miles of sea were now the only geographical barrier left. But one active line of defence remained. Invasion might seem imminent, but the Germans could not launch it as long as their ships and barges were vulnerable to the RAF. First, they had to wrest command of the air. Churchill’s message minced no words.

“The Battle of Britain is about to begin,” he told the House of Commons. “Upon this battle depends the survival of Christian civilisation. Upon it depends our own British life, and the long continuity of our institutions and our Empire. The whole fury and might of the enemy must very soon be turned on us. Hitler knows that he will have to break us in this island or lose the war. If we can stand up to him, all Europe may be freed and the life of the world may move forward into broad, sunlit uplands.

“But if we fail, then the whole world, including the United States, including all that we have known and cared for, will sink into the abyss of a new dark age made more sinister, and perhaps more protracted, by the lights of perverted science. Let us therefore brace ourselves to our duties, and so bear ourselves, that if the British Empire and its Commonwealth last for a thousand years, men will still say, ‘This was their finest hour.’”

The Luftwaffe spent an initial month softening us up with attacks on our merchant shipping in the Channel. Then it switched to day and night bombing of land-based military targets in the south of England — the aircraft factories and especially the airfields — which caused frequent air raid alerts in London. We went on duty and waited again. Day after day the RAF fought back. It was make or break, and everyone was as well aware of it as Churchill himself. If Hitler could destroy our air force, nothing would stand in the way of seaborne invasion. Day after day those on the ground, powerless to help, watched the dramas unfolding high in the sky beyond the blimps: dogfights between fighters, little victories as ack-ack guns or fighters accounted for bombers, little disasters as British planes came down in flames.

Doug and I, one day when our duties allowed, climbed the tower of St Dunstan’s for a grandstand view, cheering and groaning as if at a football match, enthralled and appalled. The occasional piece of shrapnel from an ack-ack shell fell nearby. That was what our helmets were for, to protect us. And we were here to try, in our own microscopic way, to protect our people. It was our people who were being killed up there, our people who were being killed on the ships and the airfields. They had not wanted this war. None of us had, least of all the Scouts. The scouting movement is one of peace.

A parachute floated down to land in a nearby street. In a trice two policemen were on the scene and frogmarching the airman away. A German airman. Had he wanted this war? Was he merely acting under orders? Or was he being patriotic? A funny thing, patriotism. If he had his, we had ours, poles apart. And we had another loyalty too, Doug and I.

While he was a little smaller than me, we were similar in every other way, in build and face and thinking. Sometimes we were taken for brothers, which indeed, in a manner of speaking, we were: brothers in arms. We leant on each other. His friendship — his comradeship — had buoyed me for years. Now it buoyed me more. Standing there on top of the tower, amid the bark of guns and the distant crump of bombs, we looked at each other in solemn communion. We saw that, as usual, we were thinking the same. Somehow we recognised, even at the time, that this was one of those defining milestones along our journey.

“Doug, we’re here together at the beginning. We stay together until the end, right?”

He did not bump shoulders as normally he would. Instead he replied with a hug, which he had never done before.

“And after the end too,” he said. “I hope.”

A few days later the inevitable happened. Attacks on military targets turned into attacks on civilians. On the night of 24 August 1940 came the first bombs to fall on residential areas, and they fell on Stepney.

Our personal war had begun.