Their Finest Hour

2. Blitz

We were on the night shift, starting at nine o’clock, along with four other messengers and six wardens including the sector warden. They did the rounds to check on the blackout. At half past eleven came the dismal sound of the siren — Weary Willy, as we came to call it — and they did the rounds again, making sure as far as they could, which was not very far, that people were in the few public shelters. After weeks of alerts that led to nothing, the public knew the score, and many preferred to skulk in their own homes. If their blackout was in order, however, there was no easy way of telling whether they were at home or not.

The first bomb on Stepney — the first bomb on London — fell at half past midnight. It landed, it turned out later, in the Tower Hamlets Cemetery and did no harm except to those who were already past caring. Seconds later came more bangs, closer, then beside us, then beyond. A phone call from the fire watchers at the gas works reported a fire in Emmott Street which, if it spread, would threaten the works. Our organisation was put to the test. Mr Goldstein, the warden I was attached to, rushed to the scene, ordering me to phone the Control Centre for a fire engine and then to follow him by bike. I did so. Most of the other wardens and messengers were haring out to other incidents.

It was my baptism of fire. When I caught up with Mr Goldstein we found that a bomb in the street had ripped the front off a house which backed onto the gas works. Flames were flickering from a bedroom that was spilling furniture onto the debris piled below. A few men from the works, having discovered that the water main was fractured, were forlornly trying to tackle the blaze with buckets and a midget water bowser. Mr Goldstein scribbled on a form reporting the fracture and requesting rescue and first aid parties in case people were trapped. My job now was to take the report to our post and phone the details to the Control Centre.

As I pedalled away, more bombs fell. From the same plane making a return pass? One was too close for comfort. A sharp whistle, an almighty flash, an ear-splitting boom, a stinging hail of grit, and a shock wave that sent me flying. I was on the brink of blind panic. I could feel blood trickling on my cheek. But when I picked myself up, heart racing, my limbs still worked and my bike was intact. The bomb had landed in the middle of a crossroads. The only damage, apart no doubt from broken windows, seemed to be a smashed sewer, from which a stench was already arising. When you’re afraid, your nerves are on edge. Shying at the slightest sound, at every imagined movement, I rode on. At the post I found the phone was now dead. To the Town Hall, then, a mile away, nothing else for it. Back on my bike for the next lap, as fast as the darkness allowed. As I handed over my report form at the Control Centre, there beside me was Doug handing over his.

“All right, mate?”

“Just about. But Christ almighty!”

Surprising it may sound but, like Dad, we had never sworn before, not even mildly, not even when alone together. We were not that sort. But we started that night. As we left, I noticed that his shorts were wet around the crotch. Seeing me looking at his, he looked at mine. I had not realised that they were wet too. And there were grazes on my elbow and knee. With rueful smiles and a bump of shoulders, we went our urgent ways, reassured.

As I neared St Dunstan’s, heading for Emmott Street again, my rear tyre deflated. A puncture — probably broken glass. But drawing up at the post was an AFS fire engine demanding directions. Abandoning my bike, I stood on the running board beside the driver to guide him as we went, even remembering to warn him of the hole at the crossroads. The dim headlights picked out rats scurrying around the crater.

The fire had grown since I left. “Control told us the mains are kaput,” the firemen said. “Any idea, sonny, where the nearest water is?”

This was where my hard-won knowledge of our patch paid off.

“Close by. But you’ll need axes.”

The end of Emmott Street was blanked off by a sturdy wooden fence, which they hacked through. Immediately beyond was the towpath of the Regent’s Canal. As my warden and I helped them deploy their hose, I contrived to get generous splashes onto my shorts — why parade one’s weaknesses? Then we stood back to watch the men at work.

“You had to go all the way to the Town Hall?” Mr Goldstein asked. No doubt he was wondering why I had taken so long.

“Yes. Phone dead.”

“Well done, Charlie. Just after you left there were more bombs nearby. So I was afraid …”

I liked him already. He was fatherly. He must have been a good twenty-five years older than me. This was not only my own baptism of fire, I suddenly realised. It was his too; unless he had met bombs in the Great War.

“One of them was a bit close,” I admitted. “Blew me off my bike.”

“But you’re all right?” He peered at me by the light of the flames.

“Just grazes, here and here.” I pointed.

“There’s blood on your face too. But not much. And where’s your bike?”

“At the post. I left it there. Puncture.”

He sighed. “There’s a long way to go, Charlie. We’re only at the beginning. And if a bomb has our name on it, there’s nothing we can do about it.” I was grateful that he did not ask if I had been frightened.

With adequate water now and a decent jet, the fire was soon under control. The firemen were replaced by the rescue party who, after a search, decided there were no dead or injured to retrieve, and they promised to return in the morning to make the ruins safe. The first aiders were therefore not needed. By later standards, this had been the easiest of incidents.

Back we went to the post. Mr Goldstein again thanked me for my help, and insisted on putting plasters on my very superficial hurts. Before long the others returned too. All the incidents in our sector had for the moment been dealt with. The WVS — the Women’s Voluntary Service — paid a welcome visit with their mobile canteen and dispensed tea and sandwiches. As the wardens filled in their forms, we messengers shared our experiences. Three others, like me, had had fires as well as structural damage; there must have been incendiaries among the high explosive bombs. One had had a UXB — an unexploded bomb — which was not our pigeon: all we did in such cases was cordon off the area and leave the rest to the military.

But Doug had drawn the short straw. His incident had been a direct hit, and moans were emerging from the rubble. He and his warden had helped the rescue party heave masonry and timbers away. Before too long they had the casualties out: an old man, dead, and an old woman, alive but with an arm half torn off. Doug’s fingers were raw from handling the rough debris, and on his shirt was blood.

“Not mine,” he said. “Hers. The ambulance man said she’d probably live. But …”

He was very obviously shaken, and I was worried for him. Luckily it was now the end of our shift, and the next lot of messengers arrived to relieve us. The sector warden, who was still only halfway through his stint, sent us off with thanks. Unhappy about leaving Doug alone, I walked him home, my arm tight around him. His body was trembling. He needed comfort and reassurance. If Brenda hurt herself, my standard treatment was a hug and a kiss, and usually it worked. For Doug, a squeeze, yes. After all, he had hugged me on the church tower. I wanted to kiss him too. But boys don’t kiss boys, do they? It did not occur to me to wonder why.

After a hundred yards came the sound of more bombs. Doug flinched, and we stopped.

“It’s all right,” I said, listening and watching the flashes. “They’re down Limehouse way. Nothing for us to worry about.”

We walked on.

“Fanks, mate,” said Doug suddenly, bumping my shoulder. “Better now.”

Good. The mere fact that he was talking Cockney showed he really was better. Fred had waited up, and with a brief explanation I handed Doug over. So back home, by way of the post to collect my unrideable bike. Mum, who was not on duty tonight, had also waited up, and greeted me with hugs and relief. A quick report, and I collapsed into bed. Dad would not be back until well after dawn.

When I got up, Dad was in bed, Mum was out, and I was off duty for the next two days. First I mended my tyre and, feeling that the problem was bound to happen again, bought a good supply of patches and cement. Then I went to Doug’s. He was once more his usual self.

“Sorry about last night, Charlie. And thanks for what you did.”

“Nothing to be sorry for. And you’d have done the same for me. Show me your fingers.”

Some were plastered, like my grazes.

“We need gloves,” I said. “And better shoes. But did you see that warden last night? He was wearing wellingtons and must’ve stood on something too hot. One boot had half-melted on his foot. And Scout uniforms aren’t right for this game. We need long trousers. Or boiler suits like some of the wardens wear.”

“Mmm. But we’re doing this because we’re Scouts, and we want people to know we’re Scouts.”

“Well, we’re sort of wearing two hats, aren’t we? Not just Scouts but ARP too. What about putting Scout badges on our boiler suits? Bit of both worlds.”

“Good idea. Reminds me, I must wash my uniform. Blood on the shirt, and the shorts stink of pee.”

This time we could laugh aloud about it. But Doug and Fred had to do their own laundry by hand, whereas my Mum’s pride and joy was an electric washing machine.

“Give them to me. Mum’ll throw them in with mine.”

When I got home, Dad was up and Mum was in, and the three of us talked.

“Well done, Charlie,” he said when I reached the end of my tale. “Very well done. Especially over Doug. Fourteen’s precious young to be introduced to that sort of thing. But you’ll be meeting it too, if this carries on. I think you’ll find you acclimatise quite quickly. I don’t mean become insensitive — I hope you won’t do that. It’ll just get easier to cope with injuries when you meet them. And with fear.”

I confessed that I had wet my pants. Dad chuckled.

“I’m not in the least surprised. Nothing to be ashamed of. You’ll soon get past that too.”

In which he was quite right. I never did wet them again. And Mum was happy to put Doug’s clothes in her machine.

Dad’s own night, by contrast, had been unremarkable: no bombs in his sector.

“But this is a brand-new turn,” he said, “even though we’d expected it. Some people think it was all an accident, that a rookie pilot heading for an airfield got lost and ditched his bombs at random. But there were two lots, weren’t there? Nearly three hours apart. One mistake’s possible. But two at pretty well the same point? I think they were deliberate.”

Churchill thought so too. That night the RAF was ordered to bomb Berlin, which Hitler did not like. But his retaliation was delayed. He gave us thirteen more days of strikes on the airfields alone, which proved to be the last of that round. He had failed to subdue our air force. Instead, he changed his whole strategy and threw every ounce of his might into trying to subdue our people.

* * *

On 7 September — Black Saturday, we came to call it — all hell was let loose. The Alert went just before five in the evening, the All Clear not until five next morning. Bombers by the hundred swarmed in over London. Their main target was the docks, which was where the results were the most spectacular. At the Surrey Docks just opposite us, two hundred acres of timber yards were set ablaze. The inferno took three hundred fire engines from as far afield as Bristol a week to tame, and twenty firemen died. At the West India Docks just below us, shattered warehouses spilled cascades of flaming paint and tea and rum, and streets ran with molten rubber. At Silvertown, a little further down the river, the Tate & Lyle refinery was hit and the Thames was like an ocean in hell, on fire from bank to bank with burning sugar. The River Lea was a lake of eerie blue flames from a gin distillery.

All this we saw, if we had any time to look, only from afar, for we were a good half mile away, although we could not miss the throat-catching reek of the smoke. We were preoccupied with our own woes. Stepney had about a hundred and fifty bombs that night, nearly twenty of them in our own sector around St Dunstan’s. Great gaps were torn among the houses, dense clouds of mortar dust filled the air, roads were choked with debris. First aid parties helped on the spot, stretcher parties and ambulances carried casualties to hospital, plain vans took the dead to morgues and on, as fast as possible, to communal graves. Of individual funerals, when the pace was as hot as this, there was not a chance.

If I had already had my baptism of fire, this night was my baptism of blood, real blood. A bomb had demolished a house in White Horse Road, not a hundred yards from St Dunstan’s. It was a scene that over the coming months became all too familiar: a shapeless jumble of bricks and mortar and, at all angles, timbers from the roof and floors. There was no fire, but inside the jumble someone was screaming. If you’re wounded or in shock, you scream. Of course you do, especially if you’re young. These screams sounded young. And if someone is screaming like that, they’re in desperate need of help.

I was with Mr Goldstein again, and we were alone. Our only light was our torches, which were not strong. The noise was coming from deep under the jumble, which stood maybe ten feet high. It was blood-curdling. Something had to be done, and fast. The mess would take an age to clear from above. But a jumble of rubble is not solid. It is riddled with voids, and as I looked I saw a chance.

“I’m going to try wriggling in there, sir.” I pointed to a crevice underneath a timber. I was far from fully grown yet, and Mr Goldstein was quite large and none too young.

He looked at me, weighing me up. “All right, Charlie,” he said. “But first nip back to the post. Phone Control Centre for rescue and first aid. And bring a rope from the tool chest. I’m not letting you in there without some means of getting you out.”

Luckily the phone was working tonight. Back at the scene, Mr Goldstein was shouting encouragement to the victim, and the screams were turning to whimpers. He tied an end of the rope to each of my ankles, and I crawled in, pulling myself forwards with my elbows, inches at a time. The crevice was very low. When I was about half my length inside, my torch showed an obstruction ahead. A chunk of bricks still cemented together. Torch down, tug the chunk with both hands, work it loose, manoeuvre it back past my belly.

“Got it,” said Mr Goldstein.

Pick up torch, wriggle further in. Same sort of thing again, pushing the bricks back with my feet now. And again. Until, at a guess, my head was ten feet in. I was beginning to think uncomfortably of all those tons poised precariously above. But the whimpers had given way to disjointed grunts. They were close now. A few more bricks and I was there.

My torch lit up a girl, roughly Brenda’s age, head towards me, face up, eyes closed. She was not pinned down by the rubble. What looked like a door was keeping it off her. Good. Not so good was a great gash in her neck, which was sodden with blood. Not so good either was a smell. Not the pervading smell of fire from the docks, but gas. Not poison gas, but a seepage of town gas. Was that why she was barely grunting? I had to get my hands under her arms and pull her out. But what about her poor head? Slide the tin hat off my own and onto hers as some protection. And I only had two hands, so the pulling must be done blind. Torch off, into the pocket of my boiler suit, under the Boy Scout badge. Hands, by touch now, in her armpits.

“Got her!” I called, hoping I could be heard. I was feeling queasy. “Coming out.”

Into reverse gear. But wriggling backwards is different from wriggling forwards. You need to use your knees, and there was no room to bend them. And with a load in tow … I had not foreseen this. But Mr Goldstein had.

“I’m pulling you out,” he shouted.

Firmer grip on my girl’s armpits. Ropes biting into my ankles, joints almost wrenched apart. Dragged back like a string of wagons behind a railway engine, scraping my delicate parts on the rough floor of my tunnel. A crack and a rumble as debris settled — where we had been, thank God, not where we were going. Almost clear, rising to my knees, banging my head on the tunnel portal. New voices and brighter lights. Rescue and first aid had come. My girl’s neck, what with the blood, seemed detached from her body. A final heave and she was out, her nightie in ribbons.

“Take her,” I said. “I’m going to be sick.”

I was. So too was my girl. She couldn’t be that far gone. Her parents were probably still inside there, probably dead. The rescue party would have their work cut out.

“Well done, Charlie,” said Mr Goldstein, giving me my helmet back as the stretcher party bore her away. The chinstrap was wet. With her vomit, or her blood? “That was very brave. Back to the post with you, and rest. That’s an order.”

I obeyed, but did not go in. The post was never left unmanned, and I was not up to talking. After the claustrophobic tunnel I needed space. I squatted outside in the acrid smoke and hazy glare from the docks, wishing my girl had been evacuated to safety. After a minute someone ran out of the murk and into the post, where I heard him phoning the Control Centre. It was Doug, and my drooping heart lifted. As he came out I called to him.

“Charlie!” he cried. “How’re you doing?” He flashed his torch. “You’ve torn your nice new boiler suit already!” I knew my Doug. He was better. Tonight he was pushing away his fear and revulsion. “Look, can you lend us a hand? We’ve a mountain of rubble to shift.”

For a while I shifted rubble before sheepishly catching up with Mr Goldstein. He was forgiving, and told me to go home because it was way past the end of my shift. But I couldn’t, not with the mayhem around us, not with so much to be done. I told him so, and he did not insist. So I stayed with him, at one incident following another, until the All Clear. After an hour or two more I ceased to think of anything at all.

Across London, 430 were killed that night and 1,600 badly hurt. Next morning Winston Churchill paid us a visit to see for himself. I was in bed by then and dead to the world, but they say his face was grim.

I was barely awake when Doug appeared. Mum had sent him up. As he sat on the bed we filled each other in. Our tales were similar — fires, debris, casualties, win some, lose some. He was like me today: not light-hearted, not despairing, just angry at what Hitler was doing to us.

“I’m going back tonight,” he said. “I know we aren’t on shift. But I’ve got to. Dad agrees.”

“I’m going too. If I’m allowed.” We bumped shoulders.

I found Dad in the bathroom, shaving. “I’m not happy about that, Charlie,” he said when I told him. “You don’t have to.”

“I don’t have to. But I’ve got to. There’s a difference. I can’t sit back while they kill us. Doug’s going, and Fred’s not stopping him. And if you were me, you’d go, wouldn’t you?”

Dad was not one to tell fibs. “Well, yes,” he said. “You’re right. I would.”

So we went. Mr Goldstein was in the post. “Charlie! Doug! You aren’t supposed to be here today!”

He was a part-timer too. “Nor are you,” I retorted. We laughed and got to work. Never did I call him ‘sir’ again.

* * *

From 5 September to 3 November we had sixty consecutive nights of air raids, sixty nights in relentless succession. Over the rest of November, on only three nights did bad weather leave us in peace.

We forgot what it was like not to be weary. Daylight raids, which were more easily countered by the RAF, became a thing of the past. At first there seemed to be at least some specific targets such as the docks, or when Buckingham Palace was hit for the first of many times — it was well known that the King and Queen refused to run away. But then the bombs became wholly indiscriminate. One demolished a school near the Royal Docks which was used as a rest centre for those whose homes had gone. The official death toll was 73. Rumour said it was really 450. There were many more incendiaries, and bombs became nastier. Parachute mines exploded in the air whose blast, not being cushioned by buildings or the ground, ruptured eardrums and lungs or destroyed a whole street at one go. Delayed-action bombs went off long after you assumed they were safe. Colleagues were killed, wardens and messengers, and it became a tradition to attend their funerals, even if they were communal ones, in numbers as large as duty allowed.

* * *

Weeks and months passed, one night merging in the memory into another. I could not attempt a list in date order, and even if I could it would be impossible to read. Nominal part-timers became full-timers. A routine evolved, and we learnt as we went. What was very noticeable was that we became a team. To begin with there was an almost military command structure. Wardens were the officers and messengers were the men. Wardens were charged with a wide range of responsibilities — too many — and messengers with few. It was inevitable that, given the right people, the difference was evened out. If wardens or messengers could not take it — and there were quite a few — they vanished from the scene. But in the best cases we came to know each other and to work together.

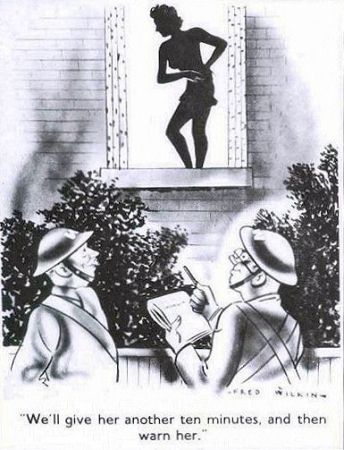

We also came to know the people of our sector and their habits: that Mr and Mrs Maniakowski at No 20, for example, always stayed at home when the siren went and hid under the stairs; that the Chou family at No 22 invariably went to the shelter; that while Mrs Jewel at No 24 went to the shelter, Mr Jewel sought solace in the bar of the George and Dragon. So if No 20 was hit, we searched the wreckage and had a good idea of where the Maniakowskis might be, alive or dead. If No 22 or No 24 were bombed we did not waste time on searching; our job, preferably before the All Clear, was to track down the Chou family or Mrs Jewel in the shelter and break the sad news that they no longer had a home. That was painful, especially because the Chou family’s English was not marvellous. If the George and Dragon took a direct hit, our job was to find Mrs Jewel and break the even more awful news to her. The trouble was that ‘our job’ often meant ‘my personal job’. For a fourteen-year-old, that was the ultimate in difficulty. I would rather confront mangled corpses who were beyond the reach of grief.

There were realms, of course, where the wardens had all the standing. One was gas. It was feared, before the war, that the Germans would throw poison gas at us. At first, the public was supposed by law to carry a gas mask at all times (though the box usually fell to pieces in a week) and the warden could book you if you did not. Wardens also had to keep an eye on the gas detectors, which relied on a yellowish green paint that changed to red in the presence of mustard gas. It was slapped on boards mounted on poles like large bird tables, or on the tops of pillar boxes, or even on dustbin lids fixed to the walls of houses. In the event of a gas attack, the warden was to go round shaking a large wooden rattle as a warning. There were decontamination teams too, although nobody ever explained to us just how they were meant to decontaminate. I had grave doubts whether all this would work in practice, but mercifully it was never put to the test. As time went on, therefore, fewer and fewer people carried masks, and before long the whole business was quietly forgotten, to nobody’s disappointment.

Blackout was a different matter. It was strictly enforced. While the warden’s rap on the door followed by a bellowed ‘Put that light out!’ might earn him the nickname of Little Hitler, persistent offenders could be prosecuted, and were. Messengers did not have the authority for that. For them — the other side of the coin — was the difficulty of riding around in the dark. With no street lights and a hooded bike lamp, it gave an eerie feeling of detachment and disorientation, compounded by the noise of bombs and guns. I was often thrown by unnoticed debris on the road. I suffered frequent punctures from broken glass or nails in timbers. Once I rode into a crater unawares and buckled my front wheel, which disabled me for a week until I found a replacement, for bike spares were as scarce as everything else.

The overall upshot was this. Although the duties of us messengers were notionally only to carry messages and tackle small fires, the hurly burly of a raid threw up umpteen jobs that somebody had to do, and the harassed wardens and rescue parties simply could not do them all. When hard-pressed, wardens might request help from other sectors, even from outside the borough. But if whole districts were being plastered, the chances were there was no spare help available. Therefore messengers, if they were trusted, were allowed or even encouraged to muscle in, just as I had been by Mr Goldstein that dreadful night in White Horse Road. When screams were coming from under a great heap of rubble, nobody — let alone you — asked if you were old enough or qualified enough to help. You just helped, as far as you could. When the injured were extracted, the first aiders got to work; but if there were no first aiders around, you did your best yourself, whoever you were, however young you might be. Thus we messengers found ourselves involved willy-nilly in rescue and firefighting and first aid. We had started, mentally, as boys. Soon, very soon, we became men.

* * *

Our worst weakness in Stepney was the provision of shelters which, despite heavy pressure from the Government and from the Communists, did not seem to be of the least interest to Morry Davis our Controller. During the attacks on the airfields, people were urged to use them, but understandably many did not. It was only when the bombs began to fall on us that the demand rocketed. A few trenches had been dug in the few open spaces but, being often a foot deep in water, were hardly popular. Some jerry-built brick and concrete public shelters had also been thrown up. Anderson shelters, basic affairs of corrugated iron sunk into the ground and covered in earth, were surprisingly effective because they flexed in a blast. But not many were installed for the simple reason that not many houses in Stepney had gardens to put them in.

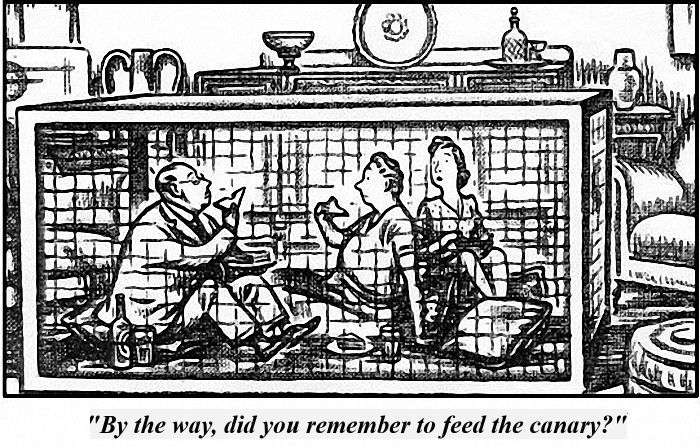

At first the most heavily used public shelter, and the most shocking disgrace, was the vast vaulted railway warehouse on Lambeth Street off Commercial Road. Known as the Tilbury, part of it was approved by the Council as a shelter for 1,600. The rest of it was not. Yet the public commandeered the whole thing. On occasion it housed 16,000. Many tried to sleep on blankets laid, in lieu of mattresses, on beds of the manure deposited by the horses that did the shunting. The chemical toilets supplied by the Council were totally inadequate even for 1,600. With 16,000, conditions were beyond description. Small surprise that before long the public — at the instigation, it is said, of Phil Piratin and the Communists — invaded the underground stations.

There were two problems here. One was that, to begin with, the Government disapproved, arguing that hordes of people on the platforms would impede the flow of trains, and tried physically to keep them out. The second was that many so-called underground stations, like our Whitechapel and Stepney Green on the District Line, were in fact barely below the surface and offered no real protection. This was driven home when a bomb hit Bank station in the City and killed over a hundred who had assumed they were safe. The first problem was solved when the Government gave way and authorised the use of underground stations, the second when it made the Central Line available. This had been largely constructed before the war but not yet completed, and it really was deep. True, the nearest Central Line stations to us, at Bethnal Green and Mile End, were inconveniently far north. But people were willing to walk fair distances in search of safety.

The underground, though hardly the height of luxury, was the best so far. Each station had an overnight supervisor. It had chemical toilets; but too few, and they overflowed. It often had a resident nurse. It usually had a few Scouts — ‘non-combatant Scouts’ they were rather unfairly called, meaning those not attached to the AFS or ARP — who would lead sing-songs to raise spirits: ‘Green grow the rushes O’ was their theme tune. They would also help with any little problem. Once, for example, I was accompanying my warden on his rounds when we looked in on a station platform. A mother, surrounded by a clutch of six kids and in floods of tears, begged him to be allowed to go up to collect a seventh whom she had carelessly left behind.

“Sorry, missis. No.”

“I’ll go fer yer, mum,” I offered. I happily talked Cockney to Cockneys. “Lend me yer key. Where d’yer live?”

She told me, and up I went. I found the toddler and brought it down, buttoned inside my boiler suit and bawling indignantly. Great was the mother’s gratitude.

Matters improved further when the Government, fed up with his obstructive behaviour, sacked Morry Davis as Controller and replaced him with the Town Clerk, who proved little better. He resigned after a month, and was replaced in turn by the Town Clerk of Islington, who was the sort of man we should have had all along. A bit later Morry Davis was convicted of fraud over a tube ticket, and that, thank goodness, was the end of him in politics.

Better still, towards the end of the Blitz, was the new Morrison shelter, a sturdy steel frame with sides of steel mesh, designed for indoor use. It could double as a ping-pong table or, covered with a cloth, as a dining table. Because it saved you having to leave the house in an alert it was very popular. It came as a kit, but having two hundred parts it was a fiddle to assemble; so ‘non-combatant’ Scouts offered their services and honed their assembly time down to twenty minutes per shelter.

* * *

High explosives apart, our greatest enemy was fire. Incendiary bombs were dropped on us by, overall, the million. They were tubes about fifteen inches long, filled with magnesium or phosphorus which ignited on impact and for a minute burned with a spitting greenish-white light before really flaring up. You had to be careful because they might contain an explosive charge designed to injure anyone trying to put them out. Outdoors, provided you caught them early enough, they were quite easy to deal with. Dump sandbags on top, such as were kept stacked at street corners, and it would kill them. Indoors, incendiaries were far more pernicious. If they broke through the slates and lodged in the roof timbers, they were hard to spot and hard to get at until it was too late and the whole thing was ablaze. And they arrived in showers of hundreds at a time. Early on I lost count of the number I had extinguished, or tried to.

For full-blown fires, Stepney had a small professional brigade, now much augmented by the volunteer AFS. If I had to single out one branch of Civil Defence for special praise, it would be the firemen. Their job was the most dangerous of all. They needed not only skill and courage, but strength and stamina. The pressure at the nozzle of the hose was so high that it was a brute to control, and if you let it go it could whizz backwards like a demented serpent and injure or even kill your colleagues. That was why there were normally two men on a nozzle. But we had been taught how to do it, and sometimes we had to. I was once at a big fire in a warehouse which three pumps were barely containing. A fireman was overcome by smoke and had to be pulled out, and I took over. There was nobody else to do it. After half an hour I was not only soaked but even more exhausted than usual. On another occasion a flying ember lodged in the gap between my shoe and my sock, to the detriment of both and, for a few days, of my foot.

* * *

Hospitals were often overwhelmed. At the end of October the big London Hospital on Whitechapel Road was hit by a bomb. This extra blow, on top of its already heavy burden, drove it to request temporary unskilled labour from Civil Defence. My sector warden asked me to go. If I could hardly call my time there a holiday, it was a change. I helped unload stretchers from ambulances and undressed patients enough for doctors to assess them. The sight, all too often, was not pleasant. I was acclimatised by now to blood, and plenty of it; but deeply gashed heads and part-severed limbs still had the power to shock. I carted amputated body parts to the incinerator. I delivered messages summoning the next of kin of serious casualties. When the siren went, I carried newborn babies in wicker baskets down to the shelter while the mothers dived under their beds.

Once there was a patient with a rare blood group who needed a transfusion. Stocks of blood being low, a call went out for anyone who was O-negative, which is compatible with every other type but is rather unusual. I was O-negative. I knew because Mum had told me so, and I remembered because I was somehow proud of being unusual. So there and then they took my blood, and made a note in case they needed more in the future. And there were other Scouts who had been at the London since the outbreak of war and were already so trusted that they worked in the operating theatres on doling out dressings or on sterilising instruments. One had become an expert at developing X-ray films. Another made corpses ready for post-mortem. The Scouts’ motto, you will hardly need reminding, is ‘Be prepared’. I had always regarded it with respect, but a slightly amused respect. Now I could see that it meant exactly what it said.

After a week I returned to ARP duties and to Doug, whose comradeship I had missed. With me I took two notes from a bigwig at the hospital addressed to my sector warden and to Fred as my scoutmaster. Because they were sealed, I could not read them. But Fred, by way of Doug, showed me his. Charlie Johnson, it said, had proved himself ‘most worthy of the great organisation of which he is a member’. That pleased me, and it pleased Fred.

* * *

For months I hardly saw Fred. We were still very much Scouts and proud of it, but as part-time messengers in theory but full-time ones in practice — and full time often meant a twelve-hour day — we simply could not attend troop meetings. In any event the parish room at St Dunstan’s had been requisitioned as a rest centre and the troop exiled to a cramped hut in the garden of Roland House. But Fred supported us all the way. If he saw little of me, he of course saw more of Doug, and was constantly sending words of encouragement. There were headlines in the papers, for instance, about a Scout who had been killed across the river in Bermondsey while rescuing a fellow messenger. He was being given a posthumous Bronze Cross, which is the Scouts’ highest award for valour.

“Quite right too,” Doug reported Fred as saying. “Though he’s far from the only one to die, and far from the only one to deserve a Bronze Cross.”

As it happened, at least three Stepney Scouts, though not from our troop, received awards that were almost as prestigious. One earned a Gilt Cross for saving a girl in a blaze. One fire watcher, who lost a leg and an eye when buried by a wall blown down in a raid, was given the Cornwell Badge for fortitude, and another a Silver Cross for gallantry in rescuing him.

* * *

After our frenetic life for the last three months, December 1940 was slightly easier, with a raid on average only every other day. And Sunday 29 December was a relatively peaceful night. For us in Stepney, that is. From the noise and the glare it was very obviously our neighbour the City of London that was being hammered. Between six in the evening and the early hours, as we pieced it together afterwards, no fewer than 24,000 HE bombs and 100,000 incendiaries were dropped, nearly all on the Square Mile. Fifteen hundred fires were started which inexorably merged into fewer big ones. Unnumbered water mains were broken. The usual practice when that happened was to draw water instead from the Thames, if it was close enough. But this raid coincided with an exceptionally low tide, and the hoses became clogged with mud. The timing, people deduced, had been deliberate. Thus the services were stretched to their limits and beyond. Fourteen firemen died that night, and 250 more were injured. A larger area was laid waste than in the Great Fire of 1666.

In the centre of the City stood St Paul’s Cathedral, the iconic symbol of London, almost the symbol of Britain. Hitler, it seemed, was intent on destroying it. Churchill, when told, ordered that it be saved at all costs. We were merely distant witnesses; but when the All Clear finally sounded we climbed St Dunstan’s tower, terrified of what we might see, or not see. The western sky was a solid blaze of orange, part-obscured by billowing clouds of black. But when the breeze blew the clouds clear, there, two miles away, was the dome of St Paul’s, intact and rising triumphant out of the inferno. Our sighs of relief were not wholly justified. What was hidden from us was the acres of desolation surrounding it.

Next day, the papers reported, President Roosevelt broadcast to the United States, expressing his shock and his sympathy for what we were suffering. He half-pledged practical support. But it was a year before it came.

* * *

Raid after raid. As dawn broke each day, people poked bleary heads up from their shelters like surfacing moles, to see what the night had left them and what it had taken away. They grumbled, and who would not? But it was remarkable how they bore their losses. With whatever was left to them, life went on. Buses still ran, even during air raids if the driver was willing, for it was at his discretion. The washing still had to be done. The milkman still did his rounds. The mail was collected and delivered, so long as there was still an address to deliver it to. We shall never surrender, was Churchill’s constant theme. And the people agreed.

* * *

By the New Year, Japan had joined the Axis. So had Hungary and Slovakia and Romania. There was heavy to-and-fro fighting in North Africa. These tidings largely passed us by. Even when news arrived that our revered founder Baden-Powell had died in retirement in Kenya, the Scouts hardly noticed. All through the rest of that winter and the spring we had enough on our plates at home.

Our fifteenth birthdays came and went almost unremarked. We were still too busy and too tired for such frivolities. On 10 May, two nights after my birthday, I was asked to report to a different sector where there was a temporary shortage of messengers. It was St George’s, which was Dad’s. I had not worked with him before. The sky being clear and the moon full — what we called a bomber’s moon — we expected a lively night, and we got it. At first the action was well to the west of us, and as I accompanied Dad on his rounds we looked in at the crypt of the church, which was a popular shelter.

“That’s one of our regulars,” he said softly with a jerk of his head. “Quite a character. Have a word with him.”

There was not much down here apart from the rows of blanketed humanity lying on the stone floor or at best on mattresses, but there were three monstrous great stone coffins. Two, with monstrous great stone lids, were presumably still inhabited by their original owners. But one had no lid, and it was occupied by a chirpy old boy who was very much alive and following us with his eyes.

“Wotcher, lad,” he said. “Seen yer around, ain’t I? On yer bike?”

“Wotcher, grandpa! Yus, that’s me. You all right here?”

“In the pink, ta.”

“You look pretty snug.”

“Bit chilly, mind. But could be a sight worse. And every morning when I comes up, what me mates always says is, ‘Well, if it ain’t old Sid! Back from the dead again?’”

He cackled, and I laughed with him. He must have trotted out his little joke umpteen times before, and would trot it out indefinitely to any willing ear. As long as he was spared.

“Sleep well, then.”

“Gorblessyer, sonny.”

We moved on to another shelter. But a new wave of bombers was coming in, and Stepney was their target. Soon after we left it, St George’s Church took a direct hit and caught fire. So did many another building. Our work was cut out in trying to cope. You have to pretend you are in control even if you are not, and that night there was much pretence. When the All Clear came at dawn, Dad was on the phone. I waited for him to finish. Then we staggered home together, each as shattered as the other. But as always he had been picking up information on his grapevine. Fourteen hospitals throughout London, he told me, had been clobbered, twenty-five fire and ambulance stations put out of action, half of the phone circuits broken, six hundred water mains fractured, and eight thousand streets blocked. Westminster Abbey and the Tower of London had been damaged and the chamber of the House of Commons destroyed.

“People are nearly at the end of their tether, Charlie. Two more raids like that, and I reckon London will go under.”

Only one more raid like that, and I reckoned I would go under. What had saved me from going under long before, I think, was the comradeship of the ARP and above all the closeness of us four, Mum and Dad and Doug and me, all working towards the same goal. That was where I found the much-needed comfort of physical contact — the hug from Mum, the shoulder-clap from Dad, the shoulder-bump from Doug — little things, but the all-important gestures of affection and support that keep you going in times of stress. Yet there comes a point, however deep the comradeship and however warm the comforting, when you know it would be an almighty relief to throw in the towel.

“Are you regretting,” Dad asked, “that you didn’t go to Sybil’s with Brenda?”

“No way! Even if the worst happens, we’ve done our best. It’s been worth it.”

That was no more than the truth. It had been worth it, both for me and for others. However weary, I had proved myself to myself. I had indeed been afraid, many a time. Never again pant-wettingly frightened, but often enough heart-stoppingly frightened. I had learned how to deal with fear and revulsion. And as far as others were concerned, which was what mattered more, I knew I had done my little bit in helping the vast and motley conglomeration that was London to survive the onslaught. But to survive for how long?

Dad clapped my shoulder, and we went to bed.

In the evening I dragged myself back on duty, trying to prepare myself for the worst. The AFS had tamed the flames at St George’s. But the church had been gutted. Although the rescue services had extracted a number of living from the crypt, my chirpy old boy in his coffin had not been spared.

There were enough messengers today, though, at the St George’s post, so I returned to St Dunstan’s and to Doug. The mere sight of him seemed a glimpse of sanity amid the madness. The previous night had been wild for him as well. Charrington’s brewery and numerous houses had been hit, with considerable loss of life. A school, a cinema and three pubs had been burnt out, but at that hour, luckily, all had been empty. Stepney Green station had been badly damaged by bombs, but by now, luckily again, nobody was using such barely-underground places as shelters.

Now it was yet another night to face. All the way through it, battling our built-up fatigue, we waited on tenterhooks for whatever nastiness the Germans might throw at us as the coup de grâce. We waited and waited. But there were no sirens, no planes, no bombs. Nothing.

Once dawn broke and it was clear that no raid was coming, our sector warden let us go. Doug was lolling where he sat, helmet drunkenly askew, fast asleep. He could hardly be woken. I was in little better shape myself. Bed beckoned us both, and the sooner the better. I phoned the St George’s post to tell Dad where I was going. As on that first night which seemed a whole lifetime ago, I walked Doug home to his flat. He was still three quarters asleep. We were too far gone to think of bumping shoulders. I managed to undress him down to his underwear, eased him into his single bed, squeezed in beside and, with an arm flung over him, went out like a light. When, late in the afternoon, Fred looked in with mugs of tea, we had not moved an inch. He made no comment at all.

That ghastly raid of the night of 10-11 May proved to be the last major one of the Blitz. A fortnight later, after nine months of hell, all but token bombing was over. The reason, it turned out, was that Hitler had for the moment given up trying to subdue us. Instead he was diverting the Luftwaffe to the invasion of Russia. At long last we could sit back and lick our many wounds.

Odious traitor though he was, Lord Haw-Haw had been right. He was no stranger to our parts, for before the war he had stood for election as a Fascist — unsuccessfully, thank God — and played a bloody part in the Battle of Cable Street. Having scarpered to Germany to avoid arrest here, he had forecast in one of his early broadcasts for the Nazis, ‘Hardest of all, the Luftwaffe will smash Stepney. I know the East End! Those dirty Jews and Cockneys will run like rabbits into their holes.’ Highly offensive that might be, but in one respect it was correct. Stepney by now had indeed been smashed. A third of all its houses, Dad said, had been destroyed.