Sioni Nionod

Chapter 5

War or no war, the next day saw us heading for Pwllheli. Tad was right. Petrol rationing had been announced and would soon be in force, and once more he was generous and offered to pay our train fares for an indefinite period. Pwllheli is only fourteen miles along the coast; but the Great Western station at Port is on the far side of town, well over half a mile from our house, and at the other end Francis Daniels lived three hundred yards from the station. Neither distance, however, daunted the energetic Yann, even on crutches. Stryd Kingshead, when we found it, proved to be narrow and ancient, and No. 20 proved to be narrow and ancient as well. The door was opened to us by a gnome of a man, bird-like in eye and movement, who looked older than his years. He welcomed us in Breton and in Welsh, and for a month thereafter virtually everything he said was in both languages.

We started off by addressing him in our normal respectful way, as is proper between youngsters and a much older adult — Mr Daniels from me, Aotrou from Yann — but he would have none of either. “Call me Francis,” he insisted. “Not Frañcez — I’ve been Francis long enough.” That Tad had taken the same line I did not find strange; but in this case, given the massive age difference, the concession was unexpected.

“If you speak Breton,” he told Yann as we sat down in the living room, “you are halfway to speaking Welsh. They are so similar.”

Francis proved a born teacher. His technique was to translate everything said in Breton, whether by Yann or himself, into Welsh, and to get Yann to repeat it. At first he kept the Welsh simple, and only gradually introduced complexities. It could have been boring in the extreme. But he made it fun. We often smiled or laughed. Not a word was said of grammatical rules, which were left to sort themselves out; and there were none of the woefully artificial phrases — I have not seen the pen of my aunt — so beloved by school textbooks. Protracted though it was by all the repetition, everything took the form of conversation on topics that would be familiar to Yann, or at least of interest to him.

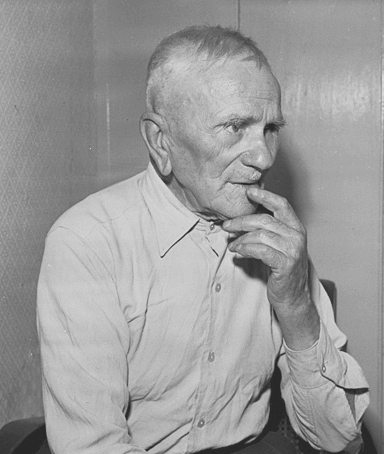

Francis began by telling us about himself, some of which we already knew from Emlyn. He had been brought to Port as a young boy and, with intervals of selling onions in the school holidays, had been educated here. He spoke briefly but with pride of teaching Breton to Lloyd George. Grown up, he had married, moved to Pwllheli, and had five children. He had served in the British army in the Great War. His wife now being dead and the children out of the nest, he lived alone. He had worked mostly as a labourer but was currently unemployed, and time therefore hung heavy on his hands. All of this, sentence by sentence, he said twice, in Breton and in Welsh, with Yann repeating the Welsh version.

If I had expected to sit on the sidelines and take no part, I was wrong. Francis then moved on to my background, asking questions in Breton before converting them to Welsh for Yann to repeat and for me to answer. If my reply was too complex, he would give Yann a simplified Breton version to understand and a simplified Welsh version to imitate. What I said about myself was, for the most part, straightforward enough although, because of our language difficulties hitherto, much of it was new to Yann. But when I revealed that I had had a twin brother, Francis instantly spotted something was amiss.

“Do you mind talking about it?” he asked, in Welsh only, his head on one side like a sparrow inspecting a crumb.

That demon, while already part-tamed, was still in residence. But I summoned up the courage and gave them the full details of how Griff had not come back from his swim, and how the family had coped, or failed to cope. At the most painful part Yann, who was beside me on the little sofa, put his hand on mine. Francis, who must have noticed, made no comment. He went on to ask about my friends. Oh dear, once again; but I had to be honest. Only Emlyn, I said, and now Yann. Again Francis noticed the awkwardness, and no doubt he also noticed the absence of any mention of a girlfriend. But once more he made no comment.

Since every sentence was spoken at least three times in one language or the other, the whole process was long drawn out. When the time came to break for food, I raised the delicate question of payment. Thank you, he said, but he wanted none. But, I insisted, he was likely to spend hundreds of hours on us. No. He welcomed the challenge and was enjoying himself immensely. He was adamant that he would take no money. He was in receipt of a pension, by courtesy of the scheme introduced by Lloyd George as Chancellor of the Exchequer, which was means-tested. If his income rose, he would lose his pension. At the very least then, I said, we should buy him a good meal every day we were with him, and to that he did agree. We went to a café beside the harbour.

In the afternoon Francis moved on, not to Yann himself but to his homeland and the Sionis’ way of life. This I found fascinating, for I had been wondering about the whole practice of seasonal migration by considerable numbers of men. Because the full picture emerged piecemeal over a number of days, it is best summarised and rearranged into coherent form.

Brittany, I learnt, is a pleasant land. The climate, tempered by the Gulf Stream, is mild and the soil fertile. Centuries ago, one quite small region round Kastell Paol and the port of Rosko had come to specialise in growing a particular variety of onion, sweet to the taste, pink in colour from the seaweed used as manure, and capable of storage for an unusually long time before sprouting or rotting. But the market for these onions elsewhere in France, which preferred different varieties, was limited; and the Breton peasants who rented the smallholdings were desperately poor and were exploited by the merchants and the rich landowners.

In 1828 one such smallholder, Henri Olivier, at the age of only twenty, tried his luck with an independent venture intended to bypass the middlemen and their extortionate rake-off. With a few friends he hired a fishing boat, filled it with onions, and sailed from Rosko to Plymouth in Devon, a large town and very much closer than Paris. Within a week they had sold their cargo and returned with heavy pockets. Others followed, and the trade grew until Britain became the principal market for the Breton crop.

A century later, fifteen hundred onion sellers a year were crossing the Channel to ports all along the English coast, up into Scotland even as far as Shetland, and — of most concern to us — round Wales to Cardiff, Swansea, Haverfordwest, Aberystwyth, Porthmadog and Bangor. They picked up the language of their hosts: English with a Yorkshire or a Scottish accent, for example, or Welsh. And because so many of them were called Jean or Yann, they acquired the nickname of Johnnie: Johnnie Onions, or Sioni Nionod in Wales. The Breton version was adopted with pride by the Sionis themselves, who revelled in their collective title of Yanniged.

Every year companies were formed of small farmers and hired workers, to sell their own onions and those bought on credit from neighbours. Each company was under a patron or boss who found some cheap room in Britain as a base in which to live and to store the stock. Time was when boys as young as nine might be brought along, but the womenfolk normally stayed behind with their smaller children to look after the farms. While in Britain, the patron bought the food and doled out money for drink and sometimes for tobacco. The Sionis handed all their takings to him and, apart from subsistence, were not paid. Only on their return were the company accounts completed, outstanding debts honoured, and the remaining proceeds handed proportionately to the men.

The crop was planted in March and harvested in July. Each company hired a fishing smack to carry them and their onions across, traditionally leaving Rosko the day after the Pardoun Santez Barba, a local pilgrimage which fell on the third Monday of July. With luck the crossing might take only two days, but bad weather might prolong it to seven or ten or even more. After five or six months, their onions sold, the Sionis would return home, often on regular ferries from the south coast. None the less, there were disasters that hit them hard. In 1898 a ferry from Plymouth was wrecked off Guernsey and eighteen onion sellers were drowned. Worse still, in 1905 the St Hilda from Southampton ran aground off Saint Malo with the loss of 125 lives, seventy of them Sionis. Many of those still involved in the trade had lost grandfathers or great-uncles in this way, or even fathers or uncles.

For a century the Sionis operated essentially on foot, although they might take a train (if there was one) from their base to more distant areas, their onion strings hanging from poles whose weight rubbed their shoulders raw. Only in the 1920s did bicycles become the norm, greater in carrying capacity than poles and cheaper than the train. With bicycles, it also became usual to return home, as well as to arrive, by fishing boat.

Almost all of this information was new to me, and much of the history was new to Yann. Even Francis learnt. It being many years since he had been in Brittany, he was eager for more recent news. Thus the conversation would be interspersed with such comments as ‘You say they still haven’t got round to repairing the west breakwater at Rosko?’ or ‘So Remon Denez is still going! He must be ancient by now!’ All this provided endless topics to elaborate on.

Francis asked Yann about his colleagues in the company, and Yann obliged with thumbnail sketches. Almost all were warm. One or two, like that of Andrev, were brief and restrained, in which case Francis took the hint and did not probe. But it gave him the opening for questions such as ‘Yves Morvan, now — is he a grandson of old Roparz Morvan from Doussen? Oh, his great-nephew. Yes, of course — his mother’s a Chapalain, isn’t she?’ Everyone in the onion region seemed know everyone else and to be related, much as applies in rural Wales. In Port, by contrast, little more than a century old, the population has converged from far afield, and I was only the third generation of our family to live in the town.

At one point, however, Francis quite inadvertently touched what was evidently a very painful spot. While asking about families in Santec he referred to someone called Pêr Kervella. Yann instantly blushed scarlet and dropped his head.

“Forget it,” said Francis at once. “Everyone has their sore points. Sorry I spoke.”

He moved on to some utterly different topic, and Yann recovered fast. Because this had all been in Breton, I had no idea at the time what the problem was. But as we were about to leave and Yann was in the toilet, Francis told me what had happened.

“The Pêr Kervella I mentioned is much my age. But I seem to remember hearing that he has a grandson who is also called Pêr, and who must be roughly Yann’s age. It sounds like dangerous territory, so be careful.”

I never did discover what Francis thought the relationship was between Yann and me. Perhaps he read more into it than was justified, though he showed no hint of disapproval. Nor of course did I have a clue why Pêr Kervella was dangerous territory. Had Yann done something to him of which he was ashamed, or the other way round? No telling; and no asking either.

* * *

The war, thus far, was proving a non-war. Virtually no military activity was reported. But after mid-September, when petrol rationing came into force, private motorists were allowed enough for only fifty miles a week, and because of shortage of coal and of customers, passenger services on the Ffestiniog Railway ceased to run. Our movements were more and more curtailed, but mercifully the Great Western was not affected and we still had access to Pwllheli. And in late September a fishing boat arrived, unmolested by any enemy, with the next instalment of onions, which was unloaded. She was the Santez Barba of Rosko, named after Barbara, the patron saint of the port.

That gave me the opportunity to ask Yann, via Francis, to describe his crossing in July. It had been rough and prolonged, and Yann shuddered as he recalled it. I asked too about working conditions here in Wales, and Yann pulled another face. Sun-kissed August days and friendly chitchat with housewives were one thing. But all too often, his colleagues had warned him, it was a case of out in all weathers, of freezing cold, and of little chance to dry sodden clothes. Though I suspect they were largely teasing, those tales of an evil climate were why he had been wearing his ridiculous long johns in high summer, as a precaution. And as for the wretched warehouse in Port and its monotonous diet … he knew, he said with his warmest smile, how well off he was with us.

So it went on, day after day except Saturdays and Sundays, week after week. We did not confine ourselves to Francis’ sitting room but, if the weather allowed, we would walk down to the Cob — for Pwllheli as well as Porthmadog has a Cob — and continue our talk as we looked out over the boats in the harbour. It became a routine but never a tedious one; and willy nilly, as a by-product, I picked up more than a smattering of Breton. Yann, as was the object of the exercise, expanded his Welsh vocabulary and his feel for the language until he was confident enough to venture away from Breton and into his own Welsh sentences. Mutations, which I gather are a pitfall to English learners, gave him no problem because Breton works similarly. At this stage Francis would correct him if necessary and get him to say it properly, or would supply a missing word. And so would I because, as Breton became a less essential part of the equation, I found myself playing an ever more active role. When alone we could now talk to each other directly, hesitantly at first and still with help from the dictionary, but with constantly improving fluency.

One day, when we had reached this point, Yann did, briefly and blushingly, resurrect the name of Pêr Kervella.

“I will tell you about him,” he said to me. “I want you to know. But not yet.”

More patience was called for, then.

This progress meant that Yann’s tuition was extended to virtually all our waking hours. Mam and Tad played their invaluable part as well, now that Yann could join in properly flowing conversations over and after meals. He elaborated, for example, on his life in Brittany: an endless seasonal round of ploughing the onion fields, planting, weeding, gathering seaweed, piling it to rot and spreading it as fertiliser, harvesting the onions, dealing likewise with the garlic and artichokes and cauliflowers which they also grew but did not market in Britain, looking after the horse, mending the cart …

“And going to Mass every Sunday?” asked Mam.

Yann lowered his eyes. “Of course,” he said. “Regular as clockwork.”

On this topic too, it seemed to me, he was uncomfortable, and he moved quickly on. Discipline for youngsters was strict, he said, and prospects for them few. Their life was tied to the land and to selling its fruits. There were no opportunities to break out and venture into new realms. What, Tad asked, did he hope to do when he was a free agent? Yann shrugged helplessly. The same, indefinitely.

This growing freedom of communication did not mean that Francis’ role was over. There were still plenty of occasions when Yann knew what he wanted to say in Breton but did not have Welsh enough to voice it, and the dictionaries were too cumbrous to constantly bother with. We continued to go to Pwllheli.

* * *

In mid-October, when Yann’s Welsh was already promisingly competent, his mind went back to what Emlyn had told us about earlier generations of Sionis. He asked Francis about his father James. A lovable man, was the candid answer, but an exasperating one, increasingly alcoholic and increasingly difficult to live with. Francis, as soon as he became engaged, had moved out and set up house in Pwllheli. His new wife was expecting their firstborn and suffering a difficult pregnancy when James’ death caught them at an awkward moment. Francis confessed he had not been able to give as much attention to the funeral as he should, and he felt guilty about it. He could not even tell us exactly where in the municipal cemetery his father was buried, because he simply could not remember. No, he said, there was no gravestone. Gravestones cost money which he did not have. And yes, he recalled poor young Herri Roignant and his untimely end; but whether Herri had a gravestone, he had no idea.

Every Sunday, as he shook our hands after the service, Emlyn would enquire how the lessons were going, and every Sunday Yann reported with enthusiasm, at first in Breton but increasingly in Welsh. He relayed our conversation about James Daniels who had no tombstone. Did Emlyn’s friend Herri, he asked, have one? No, was the reply. As Francis had said, tombstones cost more than the Sionis could afford. If Emlyn had had any money himself, he would have offered to help out, but he was then a penniless boy. His only reminders of Herri now were what he cherished in his mind — he patted his silver head — and Eifion Wyn’s poem.

“And,” he added after a visible hesitation, “a photograph. Would you like to see?”

Of course we would; and when we presented ourselves at the manse he was ready with it.

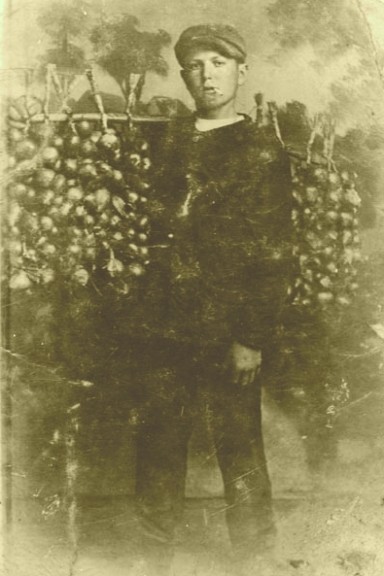

“In those days,” he said, “some of the Sionis, and especially the younger ones, would have their picture taken in a studio, posed against a painted backdrop. They would send copies home as postcards to report that all was well. Herri gave this to me shortly before he died.”

The print was faded and rather creased. It showed a lad with his onion-pole on his shoulder, the usual peaked cap and, even at that date, even at that young age, a fag in his mouth. The face did not seem, to my taste, to be particularly attractive, but then I could not see behind it as Emlyn had done. I found myself wondering if Emlyn and Herri had been more than friends. But of course I could not ask, nor even did I feel like raising the question with Yann.

“Well, I’m glad we’re not lumbered with those poles these days,” said Yann as he handed the photo back after a long inspection. “But tombstone or not, I’d like to visit his grave. Can you tell us how to find it?”

“At this end of the cemetery,” was Emlyn’s answer, “close to the top corner. But it is difficult to describe exactly. Go to the Town Hall and ask there. They keep a register and a plan. And Owen, do you think that, with Yann’s progress in Welsh, the time is ripe to introduce him to Eifion Wyn’s poem?”

Next day, then, on the way to the station, we called at the Town Hall and were given Herri’s plot number, and for good measure James Daniels’ as well. We located them on the plan, and to help pinpoint them we noted the names of the occupants of adjoining graves. We told Francis about it, and that we were planning a pilgrimage on our way home. It made him thoughtful. He excused himself for a few minutes and came back with a sealed envelope that he asked us to place on his father’s grave.

Catching an earlier train than usual back from Pwllheli, for the evenings were drawing in, we walked out of Port for half a mile along Ffordd Penamser. The sun was already hiding behind the great lump of Moel y Gêst, leaves were falling from the trees, and the bracken was turning russet. The municipal cemetery was created fifty years ago as a more convenient and spacious alternative to the overcrowded old parish churchyard, and Herri must be one of its oldest inhabitants, as Griff is one of its more recent. Overhung by waste tips from the abandoned granite quarry that scars the mountain, it has none of the open skies and aura of ancient rural peace that make Ynyscynhaiarn so special. But even in the drab browns of autumn it is not unpleasant.

I had not told Yann that Griff was buried here, and when I led the familiar way to his grave and stood before the slate headstone with its simple inscription, he gasped and his hand — much less calloused these days — reached for mine. My normal reaction on this spot was floods of tears. Today there was deep sorrow, yes, mingled with memories and gratitude, but also a feeling of closure. I felt that I was introducing Yann to my twin, not as a replacement or a substitute, but as a new friend and companion of whom I was quite sure he would approve. We said not a word. But through Yann’s grasp flowed the usual current of strength. Arms, in our body language, meant togetherness. Hand contact meant sympathy and support.

Next, the Daniels grave, an unmarked and barely visible mound. By reference to its neighbours, we found it without difficulty, except that Yann’s crutches kept sinking into the soft turf. We laid Francis’ envelope on the grass and weighted it down with a stone from the path. What it contained, we never knew, and it was not our business to ask. Yann stood silently. Earlier in our acquaintance I might have thought he was saying a prayer, but not now. Perhaps he was merely reflecting on alcoholism. This was something else that distinguished him from Griff. I had known, virtually always, what Griff was thinking. What Yann was thinking, I rarely knew. But there was still time for that to change.

Herri’s grave was equally easily located, another unmarked little mound. Now that we knew which it was, though, Eifion Wyn lifted it out of anonymity. I had brought our copy of Caniadau’r Allt, the volume of his poems that includes Yr Alltud, which means The Exile. I read it out loud. The quite simple language ought to cause Yann little difficulty.

Mae beddrod bychan, unig,

Yn erw fud fy nhref;

A llanc o Llydaw bell a gwsg

O dan ei laswellt ef.

Ni thaenir blodau arno

Ond gan y ddraenen wen;

Ac ni bu mam na mun erioed

Yn wylo uwch ei ben.

Wrth gofio’r llanc penfelyn,

Daw dŵr i’m llygaid i —

Wrth gofio’r llanc, a chofio’r llong

Aeth hebddo dros y lli.

A yw ei gwsg mor felys

A phe’n ei henfro’i hun?

Ai ynte mud freuddwydio mae

Am serch ei fam a’i fun?

Un peth a wn, pe gwyddai

Fod calon Ffrainc yn ddwy,

A bod y gelyn yn ei thir,

Na hunai ddim yn hwy.

Small is the grave and lonely

in the quiet acre of my town;

a lad from far-off Brittany asleep

beneath his sward of green.

No flowers are strewn upon it

but by the hawthorn tree;

never have mother or sweetheart

shed tears over its head.

Remembering the fair-haired lad,

water comes to my eyes —

Remembering the lad, and the ship

going without him over the sea.

Is his sleep as sweet

as if he were at home?

Or is he dreaming dumbly

of mother’s and sweetheart’s love?

One thing I know: if he knew

that the heart of France is split

and the foe is in his land,

he would no longer sleep.

Yann listened. He asked for the meanings of a few words. Then, “That last bit,” he said. “The heart of France is split. I understand the words. But what are they about?”

“It was written in 1915. During the Great War.”

“Ah. I see. But I don’t agree. Read it again.”

I did so. And a third time.

“I feel like Herri,” Yann said. “He is my friend. You know what I mean.”

Yes, I did. Had he had the word, he might have said he identified with him.

“Eifion Wyn expected him to love France,” Yann went on. “But I doubt he did, any more than I do. I like the rest of the poem, though. Very much.” He sighed deeply. “Did anyone grieve for Herri, apart from Emlyn? Does anyone in Brittany remember him now? If I go back …” — maybe that was only an imperfection in his Welsh, for he corrected himself — “when I go back, I will ask one of the Roignants. Tell me about Eifion Wyn.”

I showed him the frontispiece of the book, a studio portrait of a rather unprepossessing and severe-looking character with pince-nez, a walrus moustache, and a ridiculously large mortar board. It was clearly taken at the ceremony when the university gave him an honorary degree. We both smiled at it.

“Eifion Wyn was his bardic name,” I said. “His real name was Eliseus Williams, and he was born almost opposite us, three doors down on the other side of Lôn Garth. He died a dozen years ago, though his widow’s still alive. I never spoke to him, of course. I was too young. But I remember Tad pointing him out. His poetry … well, his job must have been a very boring one — he was clerk to a slate company — and what inspired him was his love of the outdoors. And his poems were wildly popular, and still are. They won him crowns and chairs at eisteddfodau, but he was always too shy to go up on stage to accept them.”

“What a man!” said Yann. “Is he buried in this cemetery too? I would like to see his grave.”

“No. He’s tucked up at Chwilog, ten miles west of here. Under a memorial made of great stones they brought down from Cwm Pennant. Tad was there when it was dedicated, and he said it was unveiled by Lloyd George himself — by a former prime minister, of all people. That shows how highly Eifion Wyn was thought of.”

“Would a former president of France do the same at the grave of a Breton poet? Never, never. Can we go to Chwilog?”

“Why not? It’s almost on the way to Pwllheli. Easy enough.”

“Good.”

Hard by Herri’s grave, the hawthorn tree was still there, wind-blown and gnarled. Now, with autumn fast turning into winter, it had of course no flowers, but from it Yann picked a cluster of deep red berries which he placed carefully on the grassy mound. He picked another to lay in front of Griff’s headstone, and a third for James Daniels’ grave. We walked home in silence.

We did not go to Chwilog on the way to Pwllheli; but on the following Saturday we made it an expedition in its own right. You have to change at Afon Wen, which is two stops short of Pwllheli, to the Caernarfon line, and Chwilog is the next station up. We found the cemetery, and in the middle of it Eifion Wyn’s stumpy obelisk set on a hefty base of granite. We bent a metaphorical knee before it. There were no flowers or even berries to hand, but by way of further homage Yann recited Yr Alltud, which he now had by heart, and I recited Cwm Pennant. But we were shivering in a wintry drizzle blown on a wintry breeze and did not linger, preferring to cower in the station waiting room for the next train back to Afon Wen. There at the junction it stays for a few minutes, awaiting the connecting train from Port, before it returns north once more to Caernarfon. We had a further half hour to kill before catching our own connection to Port.

Chilled to the bone, I went in search of the Gents. Yann, stronger-bladdered, stayed on the platform, repeating Yr Alltud for the umpteenth time, as the train from Port to Pwllheli pulled in and a couple of passengers got off. When I emerged, this train had already left and the Caernarfon train was just leaving. I watched it go. As usual, it was almost empty. I saw only two passengers, one of whom — good heavens above! — was utterly unmistakable.

“Yann! Yann!” I cried over the dwindling chuffs of the engine. “Did you see him? He changed here. He must have been staying with relatives in Criccieth. He must be on his way to catch the Irish Mail for London.”

“Who?”

“That old man.” I pointed to the disappearing train. “Black coat and hat. Moustache. Mane of silver hair. It was Lloyd George!”

“Good God!”

All the rest of the way home, Yann was very pensive. Over tea he asked Tad about Lloyd George and the unveiling of Eifion Wyn’s memorial.