Sioni Nionod

Chapter 6

Two days later we returned to the hospital. Another X-ray showed that Yann’s fracture was knitting nicely, and his long cast was removed and replaced by a short one covering only the shin. It delighted him to be able to bend his knee and ankle again, but to avoid putting too much weight on the healing bone he had to remain on his crutches.

All this while, his place in the Owen family, already established, was being consolidated. To use an overworked phrase, he was a ray of sunshine, unsophisticated but cheerful. Between Griff’s death and Yann’s arrival our mood had varied from the introspective to the morose. Little laughter had been heard in the house. Now it was commonplace, and from all of us. In that sense Griff, who had been a fount of laughter, had indeed returned. My prophecy that Yann could be almost another brother to me was being amply fulfilled. So too was my prophecy that he could be almost another son to Mam and Tad. They readily acknowledged it. They doted on him, and they dreaded his departure as much as I did, and as much as Yann himself.

“The tragedy is,” Tad pointed out, “that we have no legal standing whatever. Andrev is your guardian, Yann, and he calls the tune. We have no say in the matter. We may be able to keep you until the Sionis leave, and if it weren’t for the war we might try to persuade him to let you stay for longer. But I very much doubt your gang will be back here next summer.”

Yann had already turned our lives around, and for the time being we had turned his around too. We all wished it could be on a permanent basis. Ridiculous tactics suggested themselves. If only, for instance, we could hide him out of sight, so that they would not be able to take him away … but that would be tantamount to kidnapping or abduction, and it was not on. He himself took a similarly pessimistic view. He was resigned to leaving.

“There’s no point in me arguing,” he said dolefully. “Or even asking. I know what the answer would be. My uncle doesn’t begin to understand.”

On top of that, Andrev still seemed to harbour undue suspicions about his nephew. Every time he saw us he would ask if the boy was behaving himself, if he had stepped an inch out of line, if we had any complaints at all. Every time we assured him, with perfect honesty, that we could not wish for a better guest. But we still feared that when Yann was fully mended he would be dragged back to the warehouse and the marketing of onions. We therefore mounted — I unashamedly admit it — a devious conspiracy. Tad and Mam took to inviting the whole gang of Sionis to our house for a party every two weeks or so. Food and beer and whisky were laid on, and a merry time was had. These occasions were admittedly fun, and were enjoyed by all. There was much talk and even singing, to the point where the neighbours complained. But their purpose was not so much fraternal charity as to keep Andrev sweet.

At these parties Yann stuck to orange squash. We Owens, while not regular drinkers, were by no means teetotal, and in Brittany, it appeared, children were habitually introduced to wine at a surprisingly young age. But Yann, as I might have guessed from various of his comments, abhorred alcohol. He had learnt, he said, from his father’s untimely death, and saw his uncle heading in a similar direction.

In mid-November his cast was finally removed and his crutches laid aside. Once he built up strength in the leg he would be as good as new, and he revelled in his freedom. But in place of the crutches Tad gave him a walking stick that was hardly necessary, and begged him to use it whenever there might be Sionis in sight. He also told Andrev as a doctor that too much exercise would impede the recovery of the leg, and as a Welshman that Yann’s progress in the language would be set back if his tuition were cut short. This was the first moment of truth. Both arguments were considerably stretching a point, but Andrev swallowed them. What helped our cause was the fact that by November, when the Santez Barba returned to Port with the final consignment of onions, the Sionis had run completely out of stock. Andrev, therefore, could not claim that the absence of one of his team had hindered his sales. He agreed to allow Yann to stay with us until the Sionis left.

So far so good. But winning a battle is not winning the war. When Tad and Mam gingerly raised the question of Yann remaining longer, Andrev gave a categorical no, exactly as Yann had foretold. Come January or February, the boy would be going, along with the rest. He had, Andrev said ominously, to face the music. We did not understand him, and Yann would not be drawn.

Despite Tad’s plea, Yann’s Welsh was already good. His progress had been a marvellous tribute to Francis’ teaching, and these days we rarely went to Pwllheli because, as Francis himself pointed out, Breton was no longer needed. There was still tweaking and polishing to be done, especially in enlarging his vocabulary, but we could perfectly well do it at home. We therefore spent our time locally.

* * *

I was still discovering, even at this advanced stage, new facets of Yann’s character. For example, he recognised his debts. He knew how much he owed to Mam and Tad and, once he was physically a more or less going concern, he asked if there were any household jobs we could do for them. They put us on to repainting internal doors and skirting boards and banisters, and we spent companionable hours with sandpaper and paint brushes. Likewise at the hospital. Ostensibly, Yann had been patched up without charge, but I strongly suspected that Tad had reimbursed the hospital from his own pocket. I told Yann so, while warning him not to ask about it because Tad liked to keep his charity private. Yann therefore offered our services for odd jobs there. This mainly meant cleaning. The medical areas were always kept spotless, but rooms like the offices and stores were lower down the priority list and gave us many days on our knees with brush and dustpan and up stepladders with buckets of soapy water.

On one calm day we took a holiday and rowed the hundred yards to Ynys Lewis just off the harbour mouth, an artificial island created over the years by the dumpings of ships arriving in ballast. Having originated from almost anywhere around the globe, the material was of wondrous variety. Mixed with shingle that could have come from any beach were colourful stones: red sandstone that was certainly not local, shiny black obsidian that was certainly not British, and something green and igneous from who knew where. Growing on the island, too, were unfamiliar weeds and exotic shrubs, doubtless imported in the ballast as seeds. These facts would not be worth recording had they not inspired Yann to conjure up romantic scenarios of Porthmadog ships loading their cargoes at sun-kissed harbours in the Mediterranean or Caribbean, accompanied by wild native music and fuelled by plentiful wine. After all, to one who hailed from France — albeit neither French nor a drinker — the only proper fuel was wine, not rum or even beer. His visions were wildly implausible. But his tongue, very clearly, was in his cheek, and imagination was equally clearly in his soul.

I introduced him too to others of the poets who were my passion: not so much the older generations whose language can be difficult, but relatively modern ones: more of Eifion Wyn, of course, and Ceiriog, and John Morris-Jones, and Hedd Wyn, and that current local genius, T. H. Parry-Williams. To my unbounded delight, he took to them. Hitherto his only encounters with verse had been with his folk songs which I suspect, at the risk of sounding dismissive, are quite unsophisticated by comparison. But without any prompting he identified the alliteration and assonance and internal rhymes that feature so large in our poetry, and he appreciated them. On reading, for example, the painful war verse by Hedd Wyn that I quoted earlier, he instantly spotted the gwaedd and gwaed stabbing at each other from adjacent lines, and the hard letter g reverberating like gunfire a dozen times in a single stanza. I would sometimes catch him with book in hand, rolling words across his tongue; and on occasion, this sober young man confessed, he got drunk on them. Truly he had poetry in his soul, as well as romance.

Yann asked me about Hedd Wyn.

His real name, I told him, was Ellis Humphrey Evans, an ordinary young man from an ordinary farm at Trawsfynydd, whom Emlyn had known when he was minister there. In the Great War he was conscripted, much against his will, in place of his brother. Shortly before he was carted off to the front in 1917 he submitted an awdl for the forthcoming national eisteddfod. It won him the chair. But when the herald blew the trumpet and announced his name, nobody stepped up on stage. Three times the trumpet sounded, but in vain. Then the Archdruid revealed that Hedd Wyn had been killed in action at the age of thirty, and a black cloth was thrown over the chair. That occasion has ever since been known as the Eisteddfod of the Black Chair.

The peace-loving Yann sighed.

There also fell due, in the Assembly Room, the annual performance of Messiah by the Porthmadog Choral Society, whose quality is high. We all attended. Apart from snatches that I sometimes hummed, Yann had never heard anything from the classical repertoire, and his only experience of choral music beyond hymns in church was of Breton folk groups accompanied by fiddles, bombards and bagpipes. Messiah is, of course, in a wholly different league. It was sung in English, and before each number I whispered to him the opening words in Welsh so that, by converting them into Breton, he could locate himself in the Holy Writ that had surely been drummed into him in childhood; all the way through from Cysurwch, cysurwch fy mhobl — Comfort ye, comfort ye, my people — to Teilwng yw yr Oen — Worthy is the Lamb.

Emlyn was there too, just in front of us but in a sideways-facing seat, so that we were full in his view. His eye, I noticed, was often upon us, and it seemed to be wholly approving; and his glance was especially meaning when it came to Os yw Duw trosom, pwy a all fod i’n herbyn? If God be for us, who can be against us?

It was no great surprise, at this late stage of our journey together, to find that Handel knocked Yann sideways. The Hallelujah Chorus had him gripping my hand to the point of pain; and when the final Amen died away with its roll of drums and the audience rose to its feet in applause, he stayed in his seat, cheeks wet, head bowed, quivering like a leaf. No product, this, of his tuition. Like his response to poetry, it could only be innate. I felt tears on my own cheeks.

All these new insights into Yann’s nature only made more bitter the prospect of our parting. And — God! — I loved him. What I had still not worked out, even after four months in his company, was in quite what sense I loved him. He was my potential sounding board, but never yet had I sounded him. There was that one area where he remained barricaded off from me, as I was from him. By now I was privately ready for a physical consummation. Yet I was not frantic for it, for it might prove only the icing on the cake of a friendship that was already rich. I dared not risk losing the whole cake by clumsy attempts to grab the icing. Or to put it another way, if I opened Pandora’s box, what evils might pop out? Call me cowardly or muddle-headed, and I would have to agree. But having never before been in a situation remotely like this, I simply did not know how to handle it.

But yet, but yet … a partnership of heaven might be within our grasp. Things ought to be in our favour. After all, If God be for us, who can be against us? Only Andrev, maybe. And, hand in hand with Andrev, time. Time was in short supply, as too was my courage. The reason for the impasse, I suspected, lay in Yann’s embarrassment over catholic priests and in the mysterious Pêr Kervella. All I could hope for was some safe and unobtrusive opportunity for a glimpse behind his barricade.

In the end it was between us that we broke the deadlock, or went some way towards breaking it. We were as usual in Yann’s room, and once again we were chatting in a desultory way about ancient Welsh churches. I was describing Llandanwg on the coast beyond Harlech, where the little building regularly gets buried by the shifting sand dunes, and we were looking at it on the map. Yann asked who Saint Tanwg was. I admitted I had no idea, nor about the Saint Enddwyn to whom the nearby Llanenddwyn is dedicated. But other local saints, Yann remarked, pointing to the place-names on the map, were easy. Llanfair — the church of Mair, which is Welsh for Mary. Llanbedr — the church of Pedr, which is Welsh for Peter …

The hoped-for opportunity had appeared, and I seized it. “What’s the Breton for Peter?” I asked casually. “Isn’t it Pêr?”

The ploy worked. Yann blushed, as he had done whenever that name had cropped up before, and for a while he sat silent.

“It’s time I told you,” he said at last. “Told you why I’m here.”

After a pause to put his thoughts in order, it came tumbling out.

Yann was a normal boy with normal behaviour. As a matter of course, he pleasured himself, anywhere that was safe, which meant away from the house and his killjoy uncle and aunt. But one day last year, when he thought he was hidden from public sight in a copse near Santec, he was caught in the act by the parish priest. The two had never got on. The priest used to rant from the pulpit about sins of the flesh which Yann could not see as sins; and when invited to become an altar boy, Yann had turned the offer down with no hesitation at all, which did not endear him. Now, in the copse, the priest made suggestions which caused him to run away without even buttoning up. The priest took his revenge by reporting Yann’s unbridled carnality to Andrev, who wielded his cane, and next Sunday Yann was publicly denounced from the pulpit as guilty of the sin of Onan; all right-minded parents, the priest thundered, should ensure their children had no contact with moral lepers such as this.

“He didn’t actually name me,” said Yann. “But he made it crystal clear who I was and what I’d done. And from that moment on, almost all the kids avoided me. They didn’t have any choice. In Brittany, parents’ word is law, much more than it is here. Fathers might smile behind their hands while remembering what they used to do when boys, and see no real sin in it — and that applies to most of the Sionis, though not to Andrev. But mothers and grandmothers and aunts … God! They rule the roost.”

Among the youngsters, though, there was one exception, a friend of Yann’s a year or so younger, a handsome boy named Pêr Kervella, who did not ostracise him. Instead he cultivated him, and they took to pleasuring themselves in each other’s company. Pêr was an altar boy and blatantly in the priest’s good books, and one day last July he suggested they might go further and experiment with active sex together. Yann, too naïve and trusting to smell a rat, eagerly agreed. They met in the usual copse and were both in a state of high excitement when Pêr suddenly called out ‘Father!’

The priest, who must have been lurking close at hand, instantly materialised. ‘Well done, Pêr,’ he said. He advanced on Yann to lay hands on him, and Yann fought back.

‘It’s all right, Yann,’ Pêr assured him. ‘Father won’t hurt you when he does it. He’ll be very gentle.’

This double dose of treachery and hypocrisy revolted Yann’s soul; and it clearly revolted him still, for his face closed down. He seemed incapable of continuing.

“What happened?” I prompted with deep concern. My arm had been round him for several minutes.

Yann came to life and almost smiled. “I stamped on the priest’s foot. I was wearing clogs. He wasn’t.”

It was a memory, very obviously, that gave him great pleasure.

“Well, he howled and he hopped. And I ran. But I paid for it. He went straight to my uncle to complain that I’d been molesting one of his altar boys, and that I’d assaulted him. I tried to tell Andrev what had really happened, but didn’t have a chance of being believed. ‘Only sinful boys lie,’ he said. ‘Men of God do not.’ And he thrashed me again, so hard that I couldn’t sit down at Mass next day. But the priest repeated his lies from the pulpit. And on the Monday I was forced to walk on the pilgrimage. At least,” he added vindictively, “the priest was still limping too. And the day after that, Andrev and his company sailed for Port, and took me with them, at a moment’s notice, to learn the Sionis’ trade from scratch. In previous years I’d always stayed behind to help my aunt on the farm. But Andrev said it was better for everyone concerned if I was out of the way until the scandal died down.” Tears were on his cheeks.

“But will it really,” I asked, “have died down?”

“Of course it won’t. And the priest will still be after my blood. And that bastard Pêr will still be around. And the boys will still be forbidden to talk to me. But what can I do? I don’t just dislike Andrev, I’m afraid of him. After all, he’s my legal guardian. I can’t refuse to go back. And if you refused to give me up, he’d set the law on you.”

His tears were now streaming.

“But these last few months, life’s been worth living again. Betsan and Gwilym have been more kind than I knew parents could be. And you’ve been the best friend I’ve had, Owen, or ever will have. You’ve always respected me. I think you’ve been tempted, haven’t you? But you’ve never made any overtures at all. You’ve never once tried to take advantage of me like Pêr did. Thank you.”

And he broke completely down.

Oh God.

My heart bled. If once I thought I knew all the answers, I now knew not a single one. There was nothing I could do but hold him tight, still without making any overtures. Even if I felt like making them, which I did not, this was utterly the wrong moment. In hindsight, it would have been wrong all along, and I was thankful I hadn’t dared. We both had our wounds. By being almost another Griff, Yann had healed mine. By being a friend, I had healed his; but only temporarily. All I could assure him was that he had done nothing wrong.

“I don’t think I have, either,” he managed. “But you’re the first person to tell me so. What would they say in Wales?”

“I don’t know. It would vary. Some people here would certainly rant, like the catholic priest. But some would understand. I would, for a start. Griff would, if he’d still been around. Mam and Tad, I’m quite sure. And Emlyn. And pretty certainly Francis. You wouldn’t be on your own.”

“But I will be, back in Brittany. With only memories to support me.”

Behind us, out of sight, the sun was setting. Ahead, dark shower clouds were scudding across the mountains. And on them, superimposed in front of our eyes, appeared a perfect rainbow.

“Don’t despair, Yann,” I said. “Look! There’s hope. There’s always hope.”

* * *

Yann was resilient. He recovered fast, and Christmas was drawing near. Carols were heard in the streets as children begged for extra pennies. Decorated Christmas trees appeared in the front windows of the better-off; including ours, for although we had given up the custom when Griff and I left childhood behind, for Yann’s sake we revived it. And Yann, quite exceptionally, became secretive and even surreptitious. Normally we went everywhere together. But on two consecutive days he left the house by himself for short periods and apologetically forbade me to follow. I wondered why. He could hardly be shopping, for he was penniless. In the early days he had turned down the offer of pocket money, saying that because we kept him in everything he wanted, he had no need of it. In any event, wartime shortages had already caused many goods to disappear from the shelves of shops.

The answer emerged when we opened our presents on Christmas Day. My somewhat boring offering to Yann was half a dozen slim volumes of modern Welsh poetry. Mam and Tad’s, eminently practical for his return to his impoverished life at home, was a thick wad of French francs in notes that Tad had wheedled out of the bank. Yann seemed overwhelmed by both.

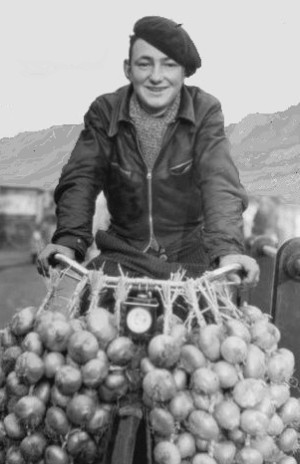

His gift to us was the reason behind his surreptitiousness: a framed photo of himself as a Sioni, inspired by Emlyn’s picture of Herri. From the warehouse, he now explained, he had temporarily retrieved his bicycle, and from Yves he had borrowed some strings of onions and enough money (“which,” he said, “I can give back now”) to pay for the photo. He had somehow persuaded the photographer to take it at the edge of the town, against a backdrop of timeless mountains rather than of tawdry High Street shops. It was a perfect memento, and it was our turn to be overwhelmed.

On New Year’s Eve we threw another party. It went well; until, that is, Andrev told us that his sales leading up to Christmas had continued at an unexpectedly high level. Customers, sensing that the Sionis would not be back next year, had been making hay while the sun still shone. Down to the very last of his stock, he had sent a telegram to Rosko asking for the boat to come and fetch them. As soon as it arrived, in perhaps a week’s time, they would load their bikes on board and go. He warned Yann to be ready. The evening, for us, was ruined by the news.

A few days later food rationing was introduced, at first only for bacon, butter and sugar but with the threat of more to come. We went to the Town Hall to collect our ration books, and Yann went with us. Because he was leaving so soon, he hardly needed a book, and we were not sure if he qualified for one. But if he did get one, he pointed out, he could bequeath it to us. He had no identity card such as had now been issued to all British subjects; but he did have his registration card, signed by the police on his arrival, which served as his work permit. On presenting it, he was given a ration book with no questions asked. The rest of the Sionis, when he told them, went to the Town Hall on the same mission.

For the last time we travelled to Pwllheli, to bid farewell to Francis, and for the last time we called at the manse, for Yann to bid farewell to Emlyn. Both were wholly sympathetic, but as powerless as us to stave off Yann’s departure. On each occasion he left in tears.

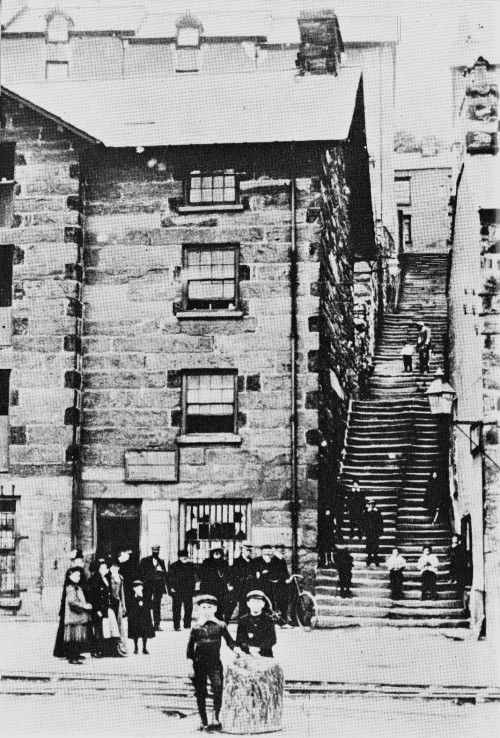

All too soon came the depressing afternoon when from our eyrie we saw the Santez Barba creep into the harbour below and moor at the quay outside the warehouse. Before long Andrev came panting up the Grisiau Mawr to tell us that they were loading the bicycles and would leave first thing next day. The pilot, he said, foretold that the weather was going to worsen, and the skipper therefore insisted on wasting no time. They would be sailing on the morning tide, and Yann must be there with his possessions by eight o’clock sharp. Andrev thanked us for our help. He knew, he said, how attached we were to our guest and, as a gift which he seemed fondly to think might soften the blow, he presented us with his last three remaining strings of onions.

He was followed, in dribs and drabs, by the rest of the Sionis, to bid their own farewell and to thank us politely for our hospitality. All of them handed over their new ration books. For the time being, although the legality of it was dubious because the things were supposed to be non-transferrable, we could draw rations for nine, on top of our own three.

When they had gone, Tad declared that he would donate the books and onions to the hospital; but that did nothing to raise our spirits. Yann packed his sack, bursting now with pass-me-ons and such goodies as the shortages allowed. We spent the final evening trying to be cheerful, insisting that before long this madness would be over and we would meet up again. But we failed miserably, and we all knew it. By that time, however far or near it might lie, who knew how the world might have changed. Yann was indeed a ship that passed in the night. Tomorrow he would be gone, and darkness and silence would return. The short-term profit from my investment had been incalculable, and had justified the whole venture. But now we were face to face with the long-term loss and all the pain that went with it. Tad had been proved right again, but never once did he say ‘I told you so.’ After all, he and Mam had profited too, and the pain lay just as heavily on them.

The pain must lie even heavier on Yann, returning to a community whose leaders regarded him as an untouchable leper. Here, we Owens had each other. There, he had nobody. How would he fare all by himself, bowed down by his burden? Had he made too free with a girl, it would no doubt have been passed over with a shrug, just as it would in Port. To make too free with a boy was a different matter, but much more so there than here. No, there were no answers.

Time would be short in the morning, and we agreed to say our proper goodbyes that night. Mam and Tad went first, alone with Yann, and I do not know what passed between them.

Then my turn came. We hugged tight, both of us sobbing, both without words. We had said it all already, and there was nothing left to say. Nothing in words. But at last our bodies spoke. I felt his arousal pressing against me, and he felt mine. When we pulled apart to search each other’s startled face, I found that the final barriers had at long last fallen. I knew exactly what he was thinking, just as I had known what my twin was thinking. Yann was indeed Griff returned, undiluted and without qualification. And he could equally read my thoughts.

They were the same. We did love one another, in every sense. To consummate that love would be eminently right. It should have happened long since. A month ago, it would have worked. Even a week ago. But not on our last night, not in our last few hours when we were exhausted by mental upheaval. Our final breakthrough had come too late. For Yann, it had been a matter of more than once bitten, several times shy. On my part, I had been over-cautious, over-chary of putting a foot wrong. Between us, all our opportunities had been missed. We still said nothing in words, but we both knew it. Which only added to the turmoil and the grief.

In a mournful mope we disentangled and went to bed, where I lay restless, doomed to solitude, my tears wetting the pillow. Outside, a wintry storm was howling, its icy breath burdened with the same sleet and the same heartache as the poet laments.

Cwsg ni ddaw i'm hamrant heno,

Dagrau ddaw ynghynt.

Wrth fy ffenestr yn gwynfannus

Yr ochneidia'r gwynt.

Codi'i lais yn awr, ac wylo,

Beichio wylo mae;

Ar y gwydr yr hyrddia'i ddagrau

Yn ei wylltaf wae.

Pam y deui, wynt, i wylo

At fy ffenestr i?

Dywed im, a gollaist tithau

Un a'th garai di?

Sooner tears than sleep this midnight

Come into my eyes.

On my window the complaining

Tempest groans and sighs.

Grows the tumult of its weeping,

Sobbing to and fro —

On the glass the tears come hurtling

Of some wildest woe.

Why, O wind against my window,

Come you grief to prove?

Can it be your heart’s gone grieving

For its own lost love?

As I now understood from first-hand experience, John Morris-Jones had known precisely what he was writing about.

Next morning, in the feeble half-light of the January dawn, we left the house to see Yann off. He was very quiet. He carried his sack slung kitbag-fashion on his shoulder, and was rigged out like an arctic voyager in long johns, double trousers and triple sweaters. But our hearts were as bitter as the weather. The wind was still blasting chill from the north east, the midwinter snows were far down the mountains, and the frost had been sharp. From our front door we turned to descend the Grisiau Mawr.

Overnight the sleet had congealed into black ice, and I did not notice. At the first step my feet went from under me. I remember the fall as if in a slow-motion film, the bounces from step to unyielding step, the fruitless flailing of arms and legs, the crack as a bone broke. After twenty-eight bounces I came to rest on the first short landing.

The agony was indescribable. “Cach!” I bawled. It did not make a ha’porth of difference that Mam and Tad were there. “O cach, cach, cach!”

The others were round me on their knees, expert hands searching out my hurts, more expert by far than mine in searching out Yann’s all those months ago. Through waves of pain there penetrated jumbled snatches of speech.

“Left femur broken,” Tad was saying. “Half way down. Thank goodness it’s not at the ball.”

“O cach!” That must have been me again.

Impatient Breton shouts were wafting up from the foot of the steps, no doubt telling Yann to hurry because he was late.

“Just a minute!” he yelled back down.

“O cach!”

“Language! Language!” some toffee-nosed passer-by reproved from the street above.

“Bear up, Owen. We’ll soon have you in the hospital.”

“Yann! Hast! Hast!”

“Go and get a wheelchair, Gwilym.”

“Risky with a broken femur, Betsan. A trolley will be better.”

Tad went. Yann had vanished. Mam and I were alone. She sat beside me, cuddling, anxious to keep me warm, while angry voices billowed up from below.

“Oh, the silly boy!” she clucked. “He’s left his sack behind.”

She rummaged in it and found sweaters that she draped around me while I shivered and swore. Eventually there was a rattling and Tad reappeared with a hospital trolley, which he parked against our front wall. Down he came and deftly hoisted me onto his shoulders in a fireman’s carry. Up the icy steps, very gingerly, to the street where he laid me out on the trolley and covered me with blankets. The pain was still intense. To it was added the burden of bleak desolation. We had not even said our final brief farewell.

They got behind the trolley and pushed. This time Tad had miscalculated. Its small wheels being designed for a smooth floor rather than a rough back street, the journey was bumpy and my leg screamed. The gradient being steep, their labour was hard. For both reasons, our progress was slow.

On the seaward side of Lôn Garth, after the houses end, the road runs along the cliff edge and looks straight down to the harbour below. And there was the Santez Barba already easing away from the quay, her sail filling, the skipper standing at the wheel, the pilot beside him, the Sionis lining the side. I could at least wave my goodbye.

“Stop!” I begged my parents. “Please stop!”

They obeyed. But as I scanned the row of Sionis I could not see him. I would have recognised him from three times as far away, but he was not on deck. He must have been sent below, in disgrace. My desolation redoubled, and I shut my eyes to contain the tears. Mam and Tad resumed their laborious pushing.

Suddenly the speed increased, and I opened my eyes.

“Yann!” I shrieked.

There he was, pushing with them, and their faces were wreathed in astonished delight.

“I’m not going,” he panted. “It’s more than I could bear. I told them. My uncle was very angry. But he couldn’t take me by force, not under the nose of the harbourmaster. And all the other Sionis were telling him to leave me alone. And the skipper said he was sailing at once, whether I was on board or not. So Andrev had no choice, short of staying behind himself.”

He let rip a whoop of defiant triumph.

“Anyway, Lloyd George told me to stay. And I’m needed here, and I need to be here, and not just until Owen’s mended. Will you have me?”

He gave us a beaming smile.

“Of course we’ll have you.” I contrived a chuckle through my agony. “And we’ll spend the rest of our lives remembering how the ship went without you over the sea. Wrth gofio’r llong aeth hebddo dros y lli.”

“There are differences, though,” he said. “That Sioni was asleep. This one isn’t. That Sioni was expected to love France enough to fight for it. This one doesn’t. He loves Wales. And he loves someone worth fighting for.”

Waves of gratitude and relief were surging over me, like the tide washing across the beach and sweeping away piles of unwelcome debris. Against all expectation, my bold investment had paid off. Yann was not after all a ship that passed in the night. Nor, Good Samaritan as he was by nature, had he passed by on the other side. But the images were becoming confused; as was my head.

A final glimpse of the harbour showed the Santez Barba, her sail now taut in the stiff north-easter, well out in the channel. Then we were there. Rough street beneath my wheels gave way to smooth floor. My hand clasped tight in Yann’s, the hospital swallowed us up.

Thus history repeated itself, if the other way round and with variations. Broken femurs are trickier than broken tibias, and the X-ray showed that my fracture was not as simple as Yann’s. Tad and Mam therefore knocked me totally out. I doubt they explored my pubic hair and anus, but I do not wish to know and have not asked. When I came round Yann was still grasping my hand; and when I was finished with, safely encased in plaster, dosed to the eyeballs with painkillers, and bundled in blankets, he installed me in a wheelchair and trundled me down the still arctic street. The wind, as fierce as before, was laden once more with stinging showers of sleet that was turning into hail. Pity the poor Sionis on their little ship.

Yann supported me into the house. Having so decisively cut himself off from his uncle, he seemed to have grown in authority. It was he who was now in command, as I had been in the aftermath of his own accident. My arm round his neck, more conscious than ever of his vitality, I hopped precariously to the kitchen. There, though the hail was rattling on the window, it was warm. He sat me down and, like an onion shedding its skins, peeled off his outer layers of clothes. Tea being the cure for all ills, he put the kettle on, and over a cuppa I could raise a whole string of questions there had been no chance to ask before. My head was still confused, and I could hardly believe what I thought had happened.

“You said you love someone,” I pointed out, starting with the most important question. “Who?”

“You, of course, silly. Who else? Ever since we first met. More and more. But I didn’t dare say so.”

“But you talked about fighting.”

“Yes. Not fighting to get you. Fighting on your behalf.”

“And what about Mam and Tad? What’ll they say?”

“No problem there. I asked them while you were asleep. And Betsan said, ‘Yann dear, it’s obvious you belong to each other. Why has it taken you so long to find out? He’s yours, provided you don’t steal him totally from us.’

“Oh God, they’re pearls among parents!”

“Oh God, they are. And what on earth were you on about? About Lloyd George telling you to stay?”

“Ah, yes, that! Well, I didn’t want to go, as you know, any more than you wanted me to. But there was no point in trying to argue with Andrev. It was only at Afon Wen that it even crossed my mind to defy him. You went to the Gents, remember? And I was on the platform reciting Yr Alltud to myself, when this old man got off the train and heard me.

“‘Great stuff, isn’t it?’ he said. ‘But how do you know it, lad?’

“‘I learnt it from my cariad,’ I said, ‘and we’ve just been to Chwilog to see Eifion Wyn’s grave.’

“‘Well done!’ he cried. ‘But where are you from? Your Welsh is good, but I can tell you’re not a Welshman.’

“‘I’m a Breton, like Yr Alltud.’

“‘Oh! But don’t you have to go back to Brittany now, and fight?’ He looked at my crutches. ‘If you’re fit enough, that is.’

“‘Yes,’ I said. ‘I’m being forced to, and I’ll soon be fit. But I don’t want to go. This is where my heart is. This is where my cariad lives. This is now my gwlad, my own land. I’d readily fight for it, even if the heart of France is split.’

“‘In that case,’ he said, ‘there’s a simple answer. Don’t go. Stick your toes in. Stay here and fight for us instead. Fight for what your heart dictates. Fight for your cariad and your gwlad. Oh, but there’s the guard blowing his whistle,’ he said. ‘I mustn’t miss my train. Lwc dda, llanc o Llydaw bell!’

“And he hopped into his carriage. And you came back and told me who he was.”

Dear God! What an encounter between a world-class statesman and an onion boy! I would have given anything to witness it. Yann had described me as his cariad, his beloved. Lloyd George himself had wished good luck to this lad from far-off Brittany. And that meeting had set Yann on the first step of his path to rebellion. At root, it was all thanks to Herri, wasn’t it? Had we not made our pilgrimage to his grave and read Eifion Wyn over it, we would never have made our pilgrimage to Chwilog, nor been on the platform at Afon Wen.

“And after that?” I asked.

“I kept on thinking. But I still couldn’t find the courage. Even after last night, when I knew for sure you wanted me. Even when we left the house this morning I was still dithering. What made up my mind was your broken thigh. The moment that happened I knew you didn’t just want me, you needed me. That’s why I left my sack at the top of the Grisiau. I was coming back for it. Coming back for you.”

My head was feeling like a cloud-shrouded mountain. His arms were round me, and once more my desire was making itself visible.

“Not yet, Owen,” he said. “Not quite yet. Wait till you’re less llygatgam. We’ve waited long enough. A bit longer won’t hurt us.”

Irrelevantly, in my befogged state, I wondered where he had come across the Welsh for cross-eyed, and shed a few more tears of joy.

Later, when I was a little less cross-eyed, Yann pointed out that my bedroom on the top floor involved an extra and unnecessary flight of stairs, which would not be good on crutches. Did he suggest that we swap rooms? Oh no. He intended to stay put and move my bed down to his own room. When my parents came home and Yann asked for a hand with shifting it, Tad had a better idea. They took out Yann’s single bed and replaced it with the double bed from the guest room. Over the outcome of that, I will draw a discreet veil.

We half-expected a lawyer’s letter from Brittany, but none came. Yann’s uncle seemed to have washed his hands of him, just as his mother had done. An easy way, perhaps, out of the scandal at home; but their loss was our gain. The line we took, irregular though Yann’s legal status here might be, was that possession is nine tenths of the law. And, following the precedent of all those thousands of Jewish children who escaped from Hitler’s clutches and, though without parents or passports or visas, had been welcomed warmly into Britain … why not a solitary Breton boy for good measure?

Meanwhile the non-war dragged on. A broken femur takes longer to mend than a tibia, and even under Yann’s tender care my recovery was slow, but by May’s end full mobility had returned. At the same time the non-war turned into full-blown war, and the last cross-channel ferry ceased to ply as the Germans invaded France and swarmed into Brittany. Of what is happening there, we have heard no word since. But one thing is sure. So long as this war lasts, there is no way that Yann can go back.

Not that he wants to. “I am a Welshman now,” he says, “and my home is here.”

No university for me, not in these circumstances. What the future holds instead, who can tell? We only know that we will face it hand in hand. But the past year has answered, beyond all argument, the question of which way my inclination lies. Mam and Tad know it full well, and rejoice in our togetherness. Emlyn, while he knows it too, says nothing out loud. But we Welsh have a proverb, as familiar to him as it is to me, on exactly the same lines as ‘If God be for us.’ A lwyddo Duw ni ludd dyn, it goes: whom God prospers, man cannot obstruct. He just watches us with a kindly eye. A Calvinistic Methodist minister, I suspect, is constitutionally incapable of winking. But I am convinced that if he could, he would.

* * *

Author’s wry postscript

Recently I myself fell and broke my thigh. The circumstances, which I will not go into, were hardly the same as with our heroes, even though the accident happened a bare half mile from the very spot where Yann came to grief. But, believe me, I did not stage it deliberately in order to learn at first hand about the pain and the subsequent healing. Nor did I use it as material for the relevant sections of this tale, for the very good reason that they had already been written. My mishap, rather, showed the fictional episodes to be so true to life that, astonishingly, not a word of them needed to be changed.

Was it precognition? Or poetic justice? Or pride before a fall?