Sioni Nionod

Chapter 4

We were almost at the end of August. The storm clouds were lowering ever darker. Civil Defence had been put on alert. War could now be averted only by a miracle. But life had to go on. Tad pointed out that in the event of hostilities, petrol would inevitably be rationed and, if Yann was to be introduced to our landscapes, it would be wise to introduce him soon. And so, for a week, I did. To save this account from degenerating into a mere travelogue, I will report less about our itinerary than about the highlights of what I learned of our guest. They were unexpected.

For the first stage we went by car to Beddgelert and Pen y Gwryd and down the Pass of Llanberis. The relatively lowland area that Yann had so far frequented, from Port north to Penygroes, is pleasant enough, but the mountains proper are altogether a different matter. Myself, I can never tire of them. For him, they were utterly outside his experience. The encyclopaedia had confirmed that, as he said, Brittany is not a mountainous land, its highest point being barely a third of the height of our Yr Wyddfa. But the Pass of Llanberis is flanked by vertiginous naked crags and its slopes are littered with cascades of boulders — car-size, lorry-size, even house-size — prised countless ages ago by glaciers or frosts from their parent rock.

“Roñfled,” was Yann’s wide-eyed comment. Not a word I recognised; but we had brought the Breton-French dictionary along, which supplied the surprising answer. Géants, giants.

At Llanberis, having eaten our sandwiches, we took to the mountain railway. Although Yann had seen trains at home, he had never travelled on them, and this one was certainly no introduction to speed, for the wicked gradient keeps it to little more than walking pace. At the summit of Yr Wyddfa we sat for an hour drinking in the view, a mighty sweep from the highest Cumbrian peaks by way of Snaefell on the Isle of Man to the Wicklow Hills in Ireland and the little Preselau in Pembrokeshire, all of them the best part of a hundred miles away or, as Yann understood it better, a hundred and sixty kilometres.

“Ec’honder,” he pronounced. Immensité, immensity, the dictionary translated when we returned to the car: a word, like roñfled, that I had hardly expected from his lips.

The following day, as a contrast, I drove him up Cwm Pennant where the hills are less wild and less stark, where the lane was narrow and deserted after the main roads of yesterday, and where the labour that fell to me was hard because the becrutched Yann could not be expected to open and shut the many gates. We lay beside the crystal waters of the stripling Afon Dwyfor, the flowery meadows loud with bees and bright with butterflies, the lower slopes dark with bracken, the higher ground purple with heather and patched silver with scree.

“Sioulded,” said Yann gazing, chin on hands. Tranquillité, tranquillity.

How appropriate. Cwm Pennant is the subject of a famous poem by Eifion Wyn, our home-grown bard from Port, whose lines are in the cultural stock of every true Welshman. It begins:

Yng nghesail y moelydd unig,

Cwm tecaf y cymoedd yw.

Lonely in the mountains’ armpit,

Valley loveliest of all vales.

And it ends:

Pam, Arglwydd, y gwnaethost Gwm Pennant mor dlws,

A bywyd hen fugail mor fyr?

Why, Lord, have you made Cwm Pennant so fair

And an old shepherd’s lifespan so short?

As we lay on the grass I began to turn the poem into French for Yann to convert into Breton. But soon I gave up. How can such things be conveyed through the filter of two dictionaries and no grammar? And how much poetry did he have in his soul? Barely literate in his own tongue, could he ever appreciate artistry in another? One day, maybe; but surely not yet. The thought gave me pause. Afraid that a touch of snobbery might be rearing its ugly head, I slapped myself mentally on the wrist.

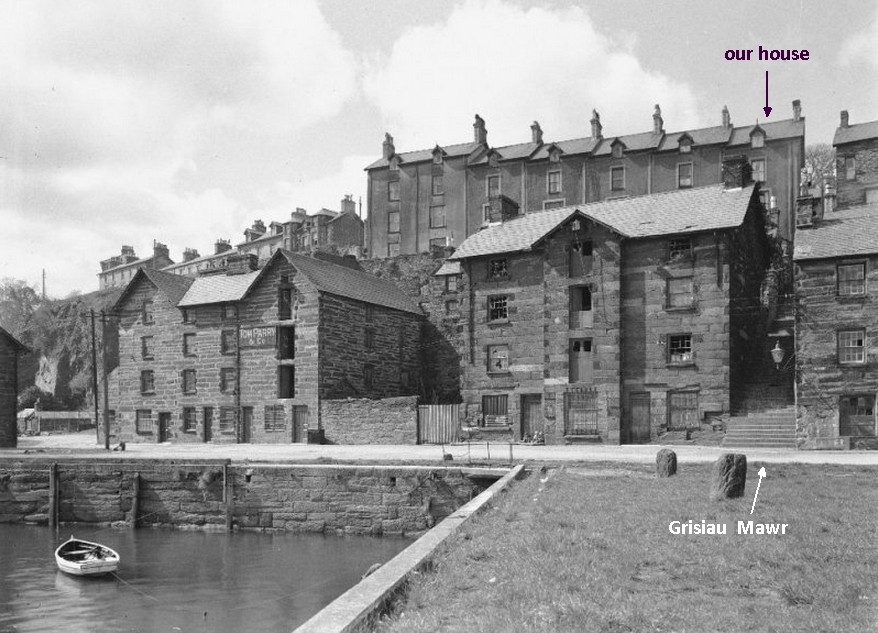

On Wednesday we sampled the Ffestiniog Railway. Yann had spent most of his waking life on his feet, and over-long immobility irked him. To reach the narrow-gauge station on the other side of the harbour, we could have walked the long way round or even driven in state, but he insisted on taking the direct route which involved the Grisiau Mawr. I was dubious, because they are steep and long — eighty-two steps, without benefit of handrails. A slip, and the fall could be nasty. But he was confident now on his crutches, and down the Grisiau we went, cautiously, with me below to catch him should he stumble. By taking breathers on the intermediate landings he coped very well.

The Ffestiniog Railway climbs up the flank of what some claim to be one of most beautiful valleys in the kingdom — although my vote would go rather to Cwm Pennant — and it is a mecca for tourists. But as on the Monday, high season though it was, rumours of war had sent the holidaymakers scurrying home. Passengers were few, and we were alone in the carriage. At one point the line plunges without warning into a half-mile tunnel. It was black as pitch, the noise was fiendish, and sulphurous smoke seeped in past the rattling windows. I felt Yann’s hand on my knee, as if he needed reassurance that I was still with him. When we emerged, he looked at me in awe.

“Ifern!” he said.

We had not laden ourselves today with the weighty dictionaries, but this time none was required. Any Welshman would understand his single word of commentary: Hell! Whether or not there was poetry in his soul, there was imagination; if, that is, there is any difference between the two. At Blaenau, however, as we waited among the grey slate tips for the train to take us down again, he had a practical question, and he had to put it in Breton. But the words were manageable.

“Penaos Emlyn deskas Brezhoneg?” he asked. How did Emlyn learn Breton?

A very interesting thought. It is surely much easier to learn a language from someone who speaks your own than from someone who does not. Had Emlyn learnt from a Welsh-speaking Breton — or a Breton-speaking Welshman — who might be able to teach me? True, Emlyn’s learning days were in all likelihood a long time ago. But it would be worth enquiring.

As luck would have it, the chance arose the moment we arrived back at Port. On crossing Pont Britannia at the head of the harbour, we bumped into Emlyn himself. He too was on his way home, and he walked with us past the slate sheds. Considerate as ever, he repeated in Breton to Yann everything he said in Welsh to me. He asked how we were getting on with the dictionaries, and I lamented the problems of multi-stage translation.

“So, Mr Williams,” I ended, “we were wondering who taught you Breton.”

“Oh, I see, I see. And you were wondering whether he could teach you too. Do you know, that sounds a very good idea. It was a Sioni, and I think he could. Yes. If you have a few minutes to spare, let me tell you about him. Why don’t we sit down?”

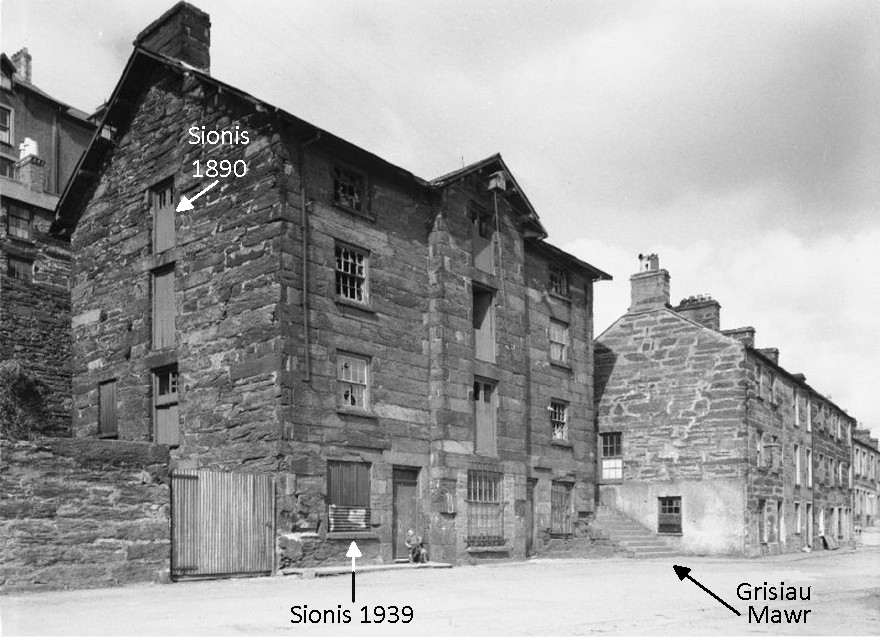

We had now reached Pencei, and we sat on the edge of the ramp where small boats are launched and hauled ashore. Directly ahead of us, fifty yards away, stood two warehouses. The one on the right was the Sionis’, with the Grisiau Mawr stepping down beside it and our house perched high above. When you grow up in a place, you take its buildings for granted, and I had never looked at this one with much care. Symmetrical with a central pedimented bay, it is built, like much of old Port, of monstrous stone blocks up to ten feet in length, and in the middle of the facade and on one gable end are hoists for lifting goods to loading doors on the upper floors. It is known locally as the Old Bank.

“Quite an impressive piece of architecture, isn’t it?” said Emlyn, gazing fondly.

“Why’s it called the Old Bank?” I asked. He was always a store of knowledge about the town’s past.

“Oh, because when it was built a hundred years ago the ground floor housed the Cassons’ Bank, which was the first bank that Port had. And when the Cassons moved out, Prichards the shipbrokers moved in, who did not bother to remove the bars on the windows. But the floors above were never much used for warehousing. At one time, for instance, a room on the top storey was occupied by an old navy man named William Griffith, who had a wooden leg and ran a school of navigation and seamanship. And in that single room he taught, and lived, and slept in a hammock slung from the rafters, and cooked; and it reeked perpetually of his only food, which was fried herring and onions.” He chuckled. “So I’ve been told — that was a century ago, long before my time.”

Yann said something, smiling. “Reminds me of old Rosko,” was how Emlyn translated him. “People like that. Places like that.”

“After he left,” Emlyn went on, “that room served for a time as Thomas Christian’s sail loft, and then the Sionis took it over for half of every year. That was the room on the top floor on the left, remember” — he pointed — “not the one on the ground floor where they are now. But it brings us on to the Sionis. I was a boy when first they came, about 1885 it must have been. In those days, you see, I lived down here on Cornhill where I had been born, and I made friends with some of the younger ones. Their Welsh was not good, and we suffered all the problems of language that you are encountering. But they let me join in when they kicked a ball around.”

He was already deep in his memories, but was still repeating everything in Breton.

“The Sioni I knew best at that stage was a boy named Henri Roignant, or Herri as they called him, who used to sell his onions up Ffestiniog way. He was not all that much older than me, and he was very kind. But I’m sorry to say he came to a sticky end. One night he went out to the pub with his colleagues and had nothing but whisky, and when they came back he was drunk and crying so loudly that he was heard by the neighbours in Harbour Terrace behind, just below your house. But eventually he calmed down and everyone went to sleep.

“Well, next morning he wasn’t in the room, and when they searched for him they found his body outside, impaled on the spikes of a gate in that coal yard between the two warehouses. Nobody had heard him go out, or knew how he had got there. I sneaked into the inquest, which was held in the News Room over there,” he nodded to the left, “though my mother was very cross about that when she found out. And the verdict was death by misadventure. There was no sign of foul play. The coroner guessed that during the night he had opened the loading door in the gable in order to relieve himself, and that being inebriated he had simply fallen out.”

Yann was following with interest and, it seemed, concern.

“Well,” Emlyn continued. “They buried him in the municipal cemetery. He was a catholic, of course, and Father Whelan from Tremadog conducted the service. But I went along, because I was terribly upset about the whole thing: the poor boy dying in so wretched a way, so unhappy, so young, so far from home … I was very fond of Herri, and I think he was of me.” He sighed. “This was in 1890, nearly fifty years ago, when I was fourteen. Herri was nineteen.”

Bells were ringing in my head. “There’s that poem by Eifion Wyn,” I put in. “Yr Alltud, The Exile. About a grave in the cemetery, the grave of a Breton boy. Was that Herri?”

“That’s right. It was.” Emlyn regarded me with approval. He was a fellow admirer of Eifion Wyn. “Show it to Yann, as soon as he’s able to appreciate it.”

Yann said something in Breton. “He says,” Emlyn translated, “as an exile of a sort himself, that he has fellow-feeling for poor Herri. And that there are plenty of Roignants still in Santec. It’s a big family. And even here in Port,” he returned to his reminiscing, “there were quite a number of Roignants around at that time. Another of them was accused of assaulting a colleague as they came back from Mass at Father Whelan’s chapel in Tremadog. He can hardly have been drunk, not on a Sunday; but he left the country before his case came to court. And there was yet another Roignant who was had up for purloining a waggon on the Ffestiniog Railway and riding down by gravity. His excuse was that he had missed the train and needed to get back to look after a sick colleague, and those were the days before they had bicycles. Whatever the rights and wrongs of it, he was still fined five shillings …

“But I’m sorry, I’m straying from the straight and narrow. Bear with me — we’re slowly coming to the point. After Herri died, I found myself wishing I could talk more easily with the Sionis; and there were two of them, father and son, who were rather different from the rest. The father was quite a pioneer. It was he who first introduced the Sionis to Aberystwyth, about 1875 I believe, and ten years later he introduced them to Port. He was different in that he settled here and acted as their local manager, although he often went back to Brittany. His name was originally Jakez Danielou, I suppose, but in Wales he called himself James Daniels.

“Well, he had a son, Frañcez or Francis, a couple of years older than me, who was born in Rosko. But when he was very young his father brought him here to Port, and he grew up completely bilingual. We were at school together — the County School, in fact — and I persuaded him to teach me Breton. Very well he did it too; and on my recommendation Mr Lloyd George himself, no less, went to him for lessons as well, although he soon became too busy to continue.” He glanced at Yann’s face, which was puzzled. “I think I need to explain who Mr Lloyd George is.”

He did so in Breton, without bothering with a Welsh version since I knew it already. David Lloyd George, he would be saying, was a towering figure: a local solicitor and friend of the common man who rose to be a reformist Chancellor of the Exchequer and the Prime Minister who arguably won the Great War for us. Although he lost power in 1922, he remained a thorn in the flesh of the Tories and of the rapidly-growing Labour Party. Now well on in years, he was still an MP, still returned home for political work and for holidays, and still remained, to everyone with a spark of liberalism in their soul, a hero.

“A Welshman!” exclaimed Yann, as translated by Emlyn. “Prime Minister of Britain! Could a Breton ever become President of France? No, never!”

“And so at last,” Emlyn resumed his tale, “I could talk properly to the Sionis, and that was when I acquired those dictionaries. But then I went off to theological college in Bala, and once ordained I was sent to Trawsfynydd, and in the Great War I served as an army chaplain, and then I spent a while at Nefyn. It was only ten years ago that I was finally posted back here to Port. But by then I had lost touch. There was a whole new generation of Sionis whom I did not know, and my Breton was rusty. James Daniels had long since come to a sad end. He had been living by himself in Cefnrodyn just behind Lombard Street here, in a mere hovel, with no furniture, not even a bed, and one morning he was found dead with only rats for company. Another victim, I’m afraid, of the bottle.”

“Lots of the Sionis,” said Yann austerely when this was translated, “still drink too much.”

“All too true.”

“Like my uncle,” Yann added.

“But by then,” Emlyn picked up his thread, “Francis had already left his father and left Port. He had married a girl from Tywyn and moved to Pwllheli, where he lives still. We meet from time to time. And he is the man you want.

“I have two suggestions to make. It would hardly be fair if you turned up unannounced on his doorstep. So shall I write him a letter, accompanied of course by a warm recommendation, and ask if he would teach you? When I hear back I will let you know. And should he be willing, Owen, it would be a kindly gesture if you had a word in your father’s ear about some remuneration. Francis, I’m sure, would not ask for any, but the last I heard he is out of work and would no doubt appreciate it. All right?

“And my second suggestion is this. Welsh is your language at home, and Yann already has a smattering. Would it not therefore be more useful all round if Francis, rather than teaching Owen Breton, taught Yann Welsh? He is equally capable of it.”

Every word of that made sense, and we agreed readily and gratefully.

“Good. I shall see to it.” Emlyn consulted his watch. “But I must get back for my tea, or my housekeeper will be reprimanding me. Good night!”

Off he went along Lombard Street, and we went home too. But on the way we looked at the southern gable end of the warehouse. There on the top floor were the loading doors from which young Herri had tumbled to his doom. A fall of a good twenty-five feet, and with spikes to land on …

The door to the Sionis’ present room being open, Yann poked a cautious nose inside — cautious, I thought, in case Andrev was around. But the rest of the company had not yet returned, and only Yves Morvan, the botteur who made the onions up into strings, was in residence. Because his job kept him in the base, he also served as the cook. But he was allowed little scope, for the authorised menu was basic. My nose told me that tonight’s meal, once again, was boiled bacon and onions. Only rarely, Yves said sadly in quite good Welsh, did Andrev release the money for a treat such as steak or rabbit. But for my benefit he demonstrated his other skills by tying about thirty onions by their tails to a core of reeds. He might make hundreds of such strings a day. It looked simple enough, if repetitive. Could Yann, I asked, do the same job? Oh no, said Yves, shocked. It took years to acquire the expertise. That came as a relief. I had feared that before long Andrev might reclaim his nephew for a warehouse-based chore.

The Grisiau Mawr proved easier for Yann uphill than down, and back at home, over a meal that was a great deal better than bacon and onions, I relayed to Tad and Mam the gist of Emlyn’s suggestions. They were happy to cough up a moderate fee for Yann’s tuition. Thank goodness once again for my parents, this time for their generosity and for being reasonably well-heeled. Had we been, like so many people, on the breadline, none of this would have been possible. Everything, in fact, was falling miraculously into place: their affection for Yann almost as a second son, his confidence in himself, his evident ease in the household, and his relationship with me. That I had found my companion I had no doubt. I thought I had found my adviser, once communication was established. Whether I had found my physical partner I had no idea, because a soul-mate, surely, is by no means necessarily a bed-mate too, any more than Griff had been. But that side of things, at that stage, did not rank nearly so high. Only time would tell.

On the last day of August, as a change from the mountains, we wandered by car far down the Llŷn peninsula. We were content, today, not to attempt much talk. For me, for the time being, Yann’s mere presence was reward enough, and I think he felt the same. There in the placid farmlands the woes of the world always seem remote, and we found a special — a final? — taste of peace. When we stopped at our furthest point, somewhere not far from Llandegwning, the windows wide open against the heat, we listened against a background of bleating sheep to one little bird twittering busily to another.

“Glabouser!” said Yann smiling, head on one side.

The word meant nothing to me. I thought he was naming the species, just as Griff would instantly have done. When I shook my head, he turned to the Breton-French dictionary. Cancanier, it said. That too was beyond me, and it had to wait until we returned home to the French-English dictionary. The answer was not the mundane blue tit or sparrow or finch I had expected, but something much more imaginative. It was tittle-tattle or gossip.

On the first of September we took to the sea, hiring a dinghy from the harbour and heading south and west along the coast. I went in some trepidation, for since Griff’s death I had never once ventured onto or into the sea. At first I rowed alone, but once we had rounded Trwyn Cae Iago and the headwind increased, Yann joined in and proved a lusty oarsman. His cast was no impediment, and every boy at Santec, I gathered, was adept not only in the onion fields but in small boats. Beyond Borth y Gêst he was exclaiming in delight at the rocks and coves that so resembled his own; but he was too tactful, I suspected, to resurrect the question of bathing. Yet my trepidation was dispelled. Not even Garreg Goch held any terror for me now. It was no longer haunted by a ghost. Griff, or an approximation to Griff, was in the boat beside me.

“He’s come back,” I sniffled, my arm on Yann’s shoulder. “You’re another Griff.”

It took a fair while before he fully understood. Then he said, very simply, “Mat. Me on balc’h.” Good. I’m proud to be.

When we got home we heard that Germany had invaded Poland. Children, the news said, were being evacuated from London. Across the country, blackout regulations were coming into immediate effect. No great problem there: this had long been prepared for, and we had curtains waiting to be put up. But the nation was now teetering on the brink.

On the second of September we ventured a mere three miles from home, to the lonely little church of Ynyscynhaiarn, islanded in a half-drained swamp. This, until the Victorians built a new church to serve the new town of Port, had been the remote and utterly inconvenient focus of the large rural parish; but now, sidelined, it was languishing. It had been founded way back in the Dark Ages, aeons before nonconformist sects were thought of, by a certain Saint Cynhaiarn. Exactly who and when he was I do not know, and I fancy nobody does. But like the Welsh, I learned, the Bretons too have countless churches dedicated to ancient Celtic saints of whom the rest of the world has never heard. Some of theirs are the same as ours, but Cynhaiarn was a stranger even to Yann.

The reason for our visit, however, was not ecclesiastical history. I wanted to show him the churchyard and the gravestones. There is a memorial, for example, to Jack Black, the name given to a boy from darkest Africa who was brought here two hundred years ago when Gêst, as our patch is called, was the most isolated of backwaters. A black face had surely never been seen in these parts before, and to the natives he must have looked as fearsomely outlandish as a Martian would to us today. So too in reverse. To him, our ways and our language must have been a massive barrier. He was none the less accepted. He learnt Welsh, he married a local girl, and they had, it is said, seven children. All of that I tried, via the dictionaries, to get across.

Language was still a massive barrier between the two of us as well. But, I had been asking myself, might music prove a link in which words did not matter? My principal goal, therefore, in bringing Yann to Ynyscynhaiarn was a gravestone inscribed with a carving of a harp and the name of David Owen, who had died in 1749 aged 29.

The faithful dictionaries were as usual with us. David Owen was a great harpist, I wrote in French for Yann to look up. A humble man. But he wrote two enduringly famous tunes.

There was Codiad yr Ehedydd, the Rising of the Lark, a melody said to have come to him on being woken by a lark after sleeping by the roadside on his way home from a late night at the pub. And there was Dafydd y Garreg Wen, David of the White Rock, which he composed on his death bed and asked to be played at his funeral. I hummed them both, and Yann listened with head on one side.

Wales is a land of music, I wrote by way of explanation; and to drive the message home I launched into the opening lines of our national anthem:

“Mae hen wlad fy nhadau yn annwyl i mi,

Gwlad beirdd a chantorion,

enwogion o fri.”

The old land of my fathers is dear to me,

Land of poets and singers,

famed and renowned.

After a few notes, to my astonishment, Yann joined in. His words were Breton, but his tune was the same. How wonderful! As every Welshman knows, our anthem was written almost a century ago, the tune by James James of Pontypridd — another young harpist — and the words by his father Evan. Brittany, therefore, must have borrowed the melody from Wales. Beaming at each other in triumph, we continued to the end.

Brittany land of music also, Yann then wrote in French, and he sang me a plaintive Breton song. It was good, as was his voice. I replied with Suo gan; and thus, perched companionably side by side on a box tomb, we alternated Breton and Welsh airs and hymns until it was time to go. Not another soul had been near the churchyard all day; visitors are few and far between. But our harmony was closer than ever.

Elated, we drove home. Clinkings from the kitchen suggested that Mam was preparing tea. Yann stumped down the stairs and flung open the door, his tenor at full blast with our joint national anthem.

“Ni Breizhiz a galon karomp hon gwir vro,” he sang. Bretons at heart, we love our true land.

I joined in with the Welsh words in what I like to call my baritone. Mam, still stirring her saucepan, took up the soprano line. Tad, who had been pottering in the garden, was drawn in and contributed his bass, conducting with a trowel. Three Welsh and a Breton sang their hearts out. On a yet higher level of elation, we ended with a round of mutual applause. And when Mam enfolded Yann in a hug, it was his turn to dissolve into tears.

“Ho tigarez,” he said, wiping his eyes. Sorry, that presumably meant. “Ken laouen,” he added. So happy.

How revealing, and how sad, that a dose of family togetherness should move him so deeply. Then it struck me. It was years since I had been so happy myself.

The third of September, however, which was Sunday, brought us to earth with a bump. We went as usual to Capel y Garth, and we took Yann with us. He was impressed by the building’s tall and ornate facade and puzzled by the simplicity inside, with its serried ranks of mahogany pews and large gallery, but of course no altar and no embellishments whatever.

“Which saint?” he whispered.

None, I tried to explain. Nonconformist chapels do not have dedications as Catholic or Anglican churches do. If anything they labour under gloomy biblical names like Ebenezer or Horeb. Methodists feel no need to bother with saints at all.

“Oh.”

While we were singing a hymn, someone came in, went up to the sêt fawr, and spoke into Emlyn’s ear. The hymn over, Emlyn relayed to the congregation the tidings, dreaded but not unexpected, that we were at war, and he offered up an extempore prayer. After the service it took much longer than usual for people to disperse, for they hung around in gloomy knots as they discussed the news. But Emlyn, once we reached him in the queue, did not forget more workaday matters. As he shook our hands, he told us that he had heard back from Francis Daniels, who would be glad to see us and suggested we call on Tuesday morning. He lived, Emlyn said, at No. 20 Stryd Kingshead, Pwllheli.

The family spent the rest of the day in dreary contemplation of the future. Here, tucked away in the north-western corner of Wales, we were safe from immediate conflict. Yet if the Germans were to invade, who knew how far they might reach? And next year I would be eighteen and liable for call-up. Large question marks now hung over my plans for university and a literary career, not to mention over Yann’s prospects as well. Mam and Tad refrained from talking about us two in particular. It was not hard to guess what was in their minds, for their memories stretched back to the Great War and its slaughter of the nation’s youth. The anguished verse came to me by Hedd Wyn, that pacifist shepherd-bard turned reluctant soldier, whose inspired journeys into poetry had been tragically cut short in the mayhem of Passchendaele:

Mae’r hen delynau genid gynt

Ynghrog ar gangau’r helyg draw,

A gwaedd y bechgyn lond y gwynt,

A’u gwaed yn gymysg efo’r glaw.

The harps to which we sang are hung

From yonder willow boughs again,

The wind is shrill with shrieks of young

Whose blood is blended with the rain.

But the lines were too painful to utter aloud.

Next morning, as I lay waking up, it occurred to me that today the schools were going back. For the first time in twelve years I would not be going too. Nor, now, was there any question of my finding a job. For the coming few months I already had a full-time one, infinitely more attractive than anything I could have expected. Flinging back the blanket, I went down to the now-regular daily ritual of helping my patient have his bath. As usual he was in bed, but instead of getting out as usual he stayed put, blushing. No difficulty in guessing why. These things happen to all of us. He was happy to be seen naked, but not to be seen excited; and in his shoes I would still feel the same. To give him time, I went to the window, my back turned. He was not wholly Griff after all, I concluded. Almost, but not quite, or not yet. Griff and I had never hidden anything at all from one another. But with Griff there had been no suggestion of sexual interest. Now, potentially, there was. For the first tme, I felt stirrings.

The bed creaked as he swung himself out of it. “Ho tigarez,” he muttered. “Trugarez.” Sorry. Thanks.

“Never mind,” I said, turning round. “It happens.”

“Ya.”

We carried on with the usual routine. A few days earlier, without any question or debate, he had started to pee in my presence, and I had followed suit. Other barriers too might yet fall. It was still early days. As I dried his buttocks I noticed that the marks had faded away.

“Dim cleisiau rŵan,” I muttered to myself. No weals now.

Yann must have understood, for he blushed but made no comment. Yes, it was still early days.

The fine weather had decisively broken, rain was sheeting down, and there was nothing to lure us from the house. I dug out the family photo album and, side by side, we leafed through it. It began with Tad’s father who, until she — and he — succumbed to a South Atlantic gale, had captained a schooner. These little ships, with a crew of a bare half dozen men and boys, had quartered the globe, carrying slate from Porthmadog to Germany or even Australia, and from there had chased cargoes wherever they offered — salted cod from Newfoundland to Gibraltar, phosphates from Venezuela to Glasgow, olive oil from Greece to Goole — until after a year or two they felt the call of home and sidled back in ballast. Thus there were ancient pictures of Port buzzing with trade, and there were faded photos of Taid and his crew and his ship at Hamburg, at Valparaiso, at Harbour Grace.

Yann was full of questions, most of which had to be put through the dictionaries. From Rosko, a town much more venerable than upstart Port, he knew how a maritime community works; or rather, in the case of poor declining Port, how it once had worked. His wider geographical knowledge, however, was tenuous. But as we explored my little atlas inherited from school, he grasped something of the immensity of the world; not just of the little local immensity of Welsh landscapes, but of the vast global immensity. His eyes shone.

There were homely pictures of Tad as a cheeky boy, as a serious medical student, as a responsible doctor. There were light-hearted pictures from Tad and Mam’s courtship and wedding. There were nostalgic and more recent pictures of young Griff and me, one of which — of two stark naked infants — curiously embarrassed me and drove Yann to peals of laughter. But from the last two years there were no pictures at all. Yann again put his hand on mine.

That one album saw us through the entire day. I only wished I could see what Yann had looked like in his formative years.

In the evening the four of us went down to Pencei in search of Andrev. We found him at the door of the Blue Anchor. Were his plans, we asked, still the same now that the crunch had come? Yes, he said, they were. The French vice-consul for North Wales had called on him in person with the order that all Frenchmen of military age were to return home at once. But Andrev was defiant. He would not change his plans.

Even, we asked, in the face of direct orders from France?

“France?” he said, and spat. Then, remembering that we were foreigners who might not understand, he condescended to explain.

There was a strong movement in Brittany for independence: not just for federation but for outright separation, inspired in the first place by the Irish revolution of twenty years before. Germany had hoped to keep Britain and France out of the war, and now that that policy had failed it would try to break the unity of France. It was already fostering the Parti National Breton, which was the spearhead of the separatist movement, and had supplied it with arms. The PNB therefore viewed the Germans with some favour, while at the same time taking a stance of strict neutrality. It was calling on Bretons not to fight for France, or for Germany either. That was why he and his company, as supporters of the PNB, would disobey the vice-consul and continue to sell their onions.

He spat again, and disappeared into the pub. “Uncle drinks too much,” repeated Yann.

But it left us thinking. We could understand. We could even, in a way, sympathise. Wales was in a similar position, yet a different one. The ruling philosophy here, with the strong support of the nonconformist churches, was liberalism, and because the English oppression of Wales was now much less than the French oppression of Brittany, nationalism had made little headway. There was indeed a separatist party, Plaid Cymru, but it was populated largely by intellectuals and language fanatics. It too urged Welshmen not to fight for England, but with only marginal success. In our constituency at the last election, when the Liberals had as usual defeated Labour, Plaid’s vote was microscopic. For myself, if — when? — I was called on to fight for Britain, I would. In Wales we had two quarrels on our hands, but our distaste for Germany far outweighed our distaste for England.

Back at home, I asked Yann, via the dictionary, what he thought about it all. He pulled a long face. He did not like Germany. He did not like the PNB which, from what he said, sounded a nasty organisation whose aims verged on the fascist. He did not even like his uncle. But he liked France less than any of them. He did not want to fight for France because it oppressed his people. Indeed, he did not like fighting at all. True, if he were Welsh, he would fight for Britain, just as I would, because here we did things better. But he was not Welsh, and before long he would inexorably be dragged back to Brittany.

We were sitting, as normal, in Yann’s room, the blackout in place. On a whim I switched off the light and took the curtain down. Outside it was almost dark. The sky was leaden. Every house was blacked out. All the street lamps were off. The wind made a mournful moan in the elecricity wires. Sullen wavelets surged across the harbour. The far-off mountains loomed murky and ominous. At least Yann was not leaving at once; but January or February suddenly felt much closer than they had. I put a comradely arm across his shoulder; something, these days, I found myself doing more and more, as much as he did to me. For neither of us was it a possessive or a seductive arm. It was a companionable arm, an arm of togetherness.

The darkness rapidly became complete. In all the hundred-odd years since it began, had Porthmadog ever been so dark? Probably not. Somewhere a light came on, provoked a distant bellow from a warden, and went out. It seemed symptomatic.