Shame and Consciences

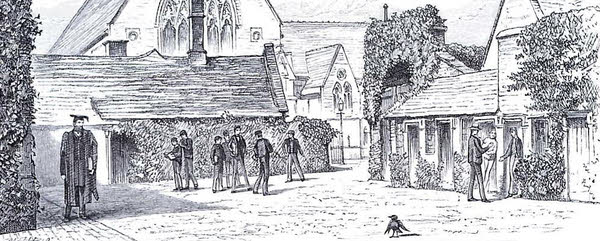

17. The fun of the fair

There were three days in the year when the market place was out of bounds, all but the pavement and the few shops around it. The rest was monopolised by the vans and booths of a travelling fair, which reached the town about the second week in March. The school took little notice of this crude and tawdry festival, but the relentless din of a steam merry-go-round filled the air, and made the night especially hideous in the town houses nearest the scene.

Nearest of all was Heriot’s house, and the worst sufferers were the four boys in the little top room with the dormer window over the street. Jan was still one of them, and Toby Bingley another. The loud-mouthed Joyce had left and the red-headed Crabtree had taken over another of the dormitories, and their tishes were now occupied by Chips and a new boy. But Jan’s was still the silent corner. Even to Chips he had little to say in front of the other two, for he was passing through another bad spell. As the merry-go-round battered him with raucous renderings of ‘Over the Garden Wall’ and ‘Lardy-dah,’ it was not his work, nor a split hand or a supposedly weak heart, that troubled him. It was the first round of the All Ages Mile that kept Jan from sleeping until the steam tunes stopped.

On the strength of his performance the year before, and because he had grown several inches since, he had been seriously fancied for a place in the Mile. Such expectations, combined with too much unwise advice, had made him sadly self-conscious and over-anxious, and his race had proved a fiasco. In the very first heat he had the bad luck to meet the ultimate winner, who the year before had been down with eye-rot. As advised, Jan dogged him instead of making the running as his flesh and blood implored. And, having no spurt, he was not only badly beaten but failed even to come in third. He was out of the Mile.

That was bad enough. Enemies of the Shockley type took care to make it worse by accusing him of conceit in anticipation of victory. Jan was depressed enough to take such slander for once to heart. Still more he felt the silence of many who had believed in him, and even the cheery sympathy of a few only aggravated his sense of failure. As for Chips and his well-meant efforts to keep the dormitory talk to any other topic, they were as maddening as the merry-go-round and its infernal ‘Lardy-dah.’ That bloody tune had accompanied his hopes and fears the night before, it had run in his head throughout the fatal race today, and now it laughed at his idiotic and unpardonable failure.

Jan was usually robust enough. But he had grown a crop of sensitivities almost worthy of Chips, except that Jan agonised over his own in grim silence. He was sixteen now, an age of surprises. It took him in more ways than one. It made him long to do startling things, and it made him do some foolish ones instead — hence his catastrophic performance in the Mile. It made him feel that he had done less than nothing so far, that he had made no mark in work or games, let alone with Evan. It made him feel that he was less than nobody, yet that there was more in him than anybody knew and he wanted them to know it. It made him feel that now he didn’t care a damn what happened to him, or what chaps thought about him, at a school he had been sent to against his will. If he was a failure, if he went on failing, well, at least it would score off those who had sent him here, and never gave him enough pocket money or wrote him an unnecessary line.

So Jan came back to where he had been when he had first arrived, but trailing all the grievances accumulated over a year and a half. By the third and last night of the fair he had the whole collection of them to brood on, a monstrous array which seemed all the more monstrous because he could not and would not speak of them to a soul. And here was that fool Chips chattering away as usual about anything and everything except the sports.

“I shall be jolly glad when this beastly old fair moves on,” Chips was saying after an interval of ‘Over the Garden Wall.’

“I don’t know that I shall,” said the new boy in Crabtree’s old corner. “It sounds rather jolly when you’re dropping off.”

Jan could have stripped every stitch off the little brute’s bed, and off the little brute himself. But the remark was very properly ignored.

“I suppose you know,” said Bingley, “that two fellows were once bunked for going to it?”

“Going to what?”

“The fair.”

“They must’ve been fools!” said Jan, opening his mouth at last.

“I thought you were asleep,” said the new boy, who had no sense.

“You keep your thoughts to yourself,” growled Jan, “or I’ll come and show you whether I am or not.”

“They were fools,” Bingley agreed, “but they were sportsmen too. They got out of one of the hill houses at night and came down in disguise, in bowlers and false beards. But they were spotted right enough, and had to go.”

“And serve them jolly well right,” said Jan cantankerously.

“I don’t call it such a crime, Tiger.”

“Who’s talking about crimes? You’ve got ’em on the brain, Toby.”

“I thought you said they deserved to be bunked.”

“So they did — for going and getting cobbed.”

“Oh, I see! You’d’ve looked every master in the face, I suppose, without being recognised?”

“I wouldn’t’ve made them look twice at me by sticking on a false beard,” snorted Jan, stung by the tone. Chips understood his mood too well to join in, but Bingley had been longer in the school than either of them and was not going to knuckle under.

“It’s a pity you weren’t here, Tiger,” he said, “to show them how to do it.”

“It’s a thing any fool could do if he tried. I’d back myself to get out of this house in five minutes.”

“Not you, old chap!” said Chips, misguidedly entering the discussion after all.

“I would. I’d do it tomorrow if the fair wasn’t going away.”

Bingley began to jeer. “I like that, when you jolly well know it’s going!”

“I’ll go tonight if you say much more, you fool!”

Jan’s bed-springs twanged as he sat bolt upright.

“You know you wouldn’t be such an idiot,” said Chips earnestly.

“Of course he does!” jeered Bingley. “Nobody knows it quite so well.”

There was a moment’s pause, filled by a blast of sound from the market place and then by the thud of bare feet on the floor.

“Surely you’re not going to let him dare you —“

“Not he. Don’t you worry!”

“Thank you, Toby,” said Jan in a strange voice, sliding into his trousers in the dark.

There was a jingle of curtain-rings and, in defiance of all the rules, Chips was out of his tish. He appeared dimly at the foot of Jan’s, and Bingley was already peering over the partition.

“Are you off your chump?” demanded Chips.

“Not he,” said Bingley again. “He’s only bunging us up!” He might have been an infant devil, but he was really only an incredulous, irritated and rather excited schoolboy.

“You’ll see directly,” muttered Jan, slipping his braces over his night-shirt.

“You’re bound to be caught, and bunked if you’re caught!” Chips was desperate now.

“And a good job too! I’ve had about enough of this place.” This was the Jan of their very first term together.

“And it’s raining like the very dickens!” That was the new boy, the little sinner, who seemed to take this enormity as a matter of course.

“So much the better. I’ll take a brolly. Less chance of being seen. You see if I don’t bring you all something from the fair.”

“It’s something he’s gone and got today,” whispered Bingley, to placate Chips. “It’s all a swizzle, you’ll see.”

“You look out of the window in about five minutes,” retorted Jan from the door, “and p’r’aps you’ll see!”

Out he stole, boots in hand, leaving Chips in muzzled consternation in the doorway.

The rain pelted on the skylight over the stairs, and Jan was glad. He foresaw the complication of wet clothes, but as a mere umbrella among umbrellas he stood a fair chance of not being seen. It was still only a chance, but that was half the fun. And fun it was, though a terrifying form of fun, though he was already feeling a bit unsound about the knees. But he had to go on with it. There was no question about that, and no looking back at the ridiculous taunts and impulses which had led to this mad adventure. Conversation had ceased in the first of the two dormitories below, but still murmured from the second. The lead-lined stairs struck, through his socks, a chill to his marrow. He began to think he really was a fool, but he would look a bigger one if he went back now. The flags of the corridor were colder than the stairs, and the slate table on which he sat to put on his boots was colder than the flags.

His first idea had been to get out into the quad, as he had got out on his very first morning, through the hall windows. But the rain spoilt that plan. The umbrellas were kept in the lower study passage, which was locked — how was he to break in? No, if he wanted an umbrella he must borrow Heriot’s. That was a paralysing alternative, but the only one. The hat-stand was in the entrance hall, just on the other side of the green baize door. Dear old Bob notoriously sat up till all hours, and his study led off the dining room which led off the hall, so there were probably two closed doors between Jan and him. It was a risk to be taken.

But was it? The image of Robert Heriot suddenly loomed up in Jan’s mind, of Heriot peaceably smoking his pipe in his inner sanctuary, of Heriot hearing a furtive footstep, of Heriot leaping out, beard bristling and spectacles flashing, to arrest the intruder. To be caught by Heriot of all men! The one master with whom the boldest boy never dared take a liberty, the one whose good opinion was best worth having and perhaps the hardest to win. Why had he not thought of Heriot before? To think of him now was to abandon the whole adventure in a panic. Better the scorn of fifty Bingleys for the rest of term than the wrath of one Heriot for a single minute.

Jan found himself creeping upstairs again. Through the door of the lower dormitory came the guttural voice of Shockley holding forth about something. It was Shockley who had said the hardest things about Jan’s running, in just that hateful voice. It was Shockley who would have the most and worst to say if he heard that his pet hate had made a chicken-hearted fool of himself. And then life would be even worse than it was now, school a rottener place, himself a greater nonentity than ever. That was unthinkable too. A minute ago there had been some excitement in life, for once he had felt somebody.

“I’m blowed if I do,” thought Jan, and crept down again to the green baize door. It opened without a sound. A light was burning in the entrance hall beyond. The dining room door was providentially shut. Here was Heriot’s umbrella, and it was wet. Over it hung a soft felt hat and an Irish tweed cape that was wet about the hem. So old Bob Heriot had been out and had come in again. It was still short of eleven. Unless tradition lied, he was safe in his study for another hour.

Cold feet gave way to almost drunken impudence. In a twinkling Jan put on Heriot’s coat and hat. It would give them something to talk about, whether he was caught or not. He would contribute to the annals of the school. The front door was still unlocked. Out in the rain, he opened the umbrella and held it low over his head. Thrusting a hand deep into a pocket, he encountered one of Heriot’s many pipes. Next instant the pipe was between his teeth, and from the opposite pavement of a dripping and deserted street he was flourishing the umbrella and pointing out the pipe to three white faces at a window in the shiny roof.

He would not have cared, at that moment, if he had known he was going to be caught the next. And nobody was there to catch him, not in the street. But, no further away than he could have thrown a fives ball, the glare of the market place lit up the stone front and archway of the Red Lion, and the blare of the steam merry-go-round thundered out as Jan marched under Heriot’s umbrella into the zone of light.

He wears a penny flower in his coat —

Lardy-dah —

And a penny paper collar round his throat —

Lardy-dah —

In his hand a penny stick,

In his tooth a penny pick,

And a penny in his pocket —

Lardy-dah, lardy-dah —

And a penny in his pocket —

Lardy-dah!

Jan had picked up the words from some fellow who used to sing such rubbish to a worse accompaniment on the hall piano, and they ran in his head with the outrageous tune. They reminded him that he had scarcely a penny in his own pocket, thanks to his generous people in Norfolk, and for once it was just as well. Otherwise he would certainly have taken a public ride, in Heriot’s distinctive and well-known garb, on one of ‘Collinson’s Royal Racing Thoroughbreds, the Greatest and Most Elaborate Machine Now Travelling.’

Last nights are popular nights, and the fair was crowded in spite of the rain. Round and round went the little wooden horses, carrying half the young blood of the little town. Jan tilted his umbrella to have a look at them. Their shouts were drowned by the din of the steam organ, but as they whirled past him their flushed faces were illuminated by a great flare-light. One purple complexion he recognised as the pace slackened. It was Mulberry, that scoundrel of evil memory, swaying in his stirrups and whacking his wooden mount as though they were in the straight.

The deafening blare sank to a dying whine, the flare-light sputtered audibly in the rain, and Jan jerked his umbrella forward as the dizzy riders dismounted. He turned his back on them, contemplating the cobbles under his nose and the lighted puddles that ringed them like meshes of liquid gold. He watched for the unsteady corduroys of Mulberry, and withdrew as they came near. But there was no sure escape short of leaving altogether, for the market place was little larger than a tennis court, half of it covered with the merry-go-round and another quarter with stalls and vans.

One of the stalls displayed a sign which seemed to attract little custom.

Rings Must Lie to Win

WATCH-LA!

2 Rings 1d.

all you ring you have

The watches lay in open cardboard boxes on a sloping board behind a table. There was a supply of wooden rings that just fitted round the boxes. Jan watched one oaf run through several coppers, his rings always lying between the boxes or on top of one. Jan felt it was a case for a spin, and he longed to have a try with that cunning left hand of his. But he only had twopence on him, and his first need was twopence-worth of evidence that he really had been to the fair. Yet what trophy could compare with one of those cheap watches in its cardboard box?

It so happened that Jan had a watch of his own worth everything on sale at this shoddy fair, but he would almost have bartered it for one of these, to show the top dormitory the kind of chap he was. He did not normally see himself in heroic terms, but he was in abnormal mood tonight, and the need to seem heroic lay behind this whole escapade. With a sudden determination, and a quick glance to make sure that Mulberry was not dogging him, he produced a penny.

“Two rings,” said the fur-hatted stallholder, handing them over. “An’ wot you rings you ’aves.”

The steam fiend broke out again with ‘Over the Garden Wall’ as Jan poised his first ring. A back-handed spin sent it well among the watches, and it went on spinning until it settled at an angle over one of the boxes.

“Rings must lie flat to win,” said the fellow in the fur cap, with a quick squint at Jan. “Try again, mister. You’d do better with less spin.”

Jan grinned dryly and decided to put on a bit more. He had heard his father driving hard bargains in the Saturday market at Middlesbrough. Old Rutter had known how to take care of himself across any stall or barrow, even when he was as unsteady on his legs as Mulberry. Jan felt equally in command as he poised his second ring. It skimmed gracefully away, circled one of the square boxes, and was spinning down like a nut on its bolt when the man in the fur cap whipped a finger between the ring and the sloping board.

“That’s a near one, mister!” he cried. “But it don’t lie flat.”

Nor did it. The ring had jammed obliquely on the box.

“It would’ve done if you’d left it alone!” shouted Jan above the steam fiend’s roar.

“That it wouldn’t! It’s a bit of bad luck, that’s wot it is. Never knew it to ’appen before, I didn’t. But it don’t lie straight, now do it?”

“It would’ve done,” replied Jan through his teeth. “And the watch is mine, so let’s have it.”

What precisely happened next, Jan was never sure, for his head swam. He knew he was sprawling across the table, he had seized the watch that he had fairly won, and the ruffian had seized his wrist. That horny grip remained like the memory of a handcuff. The thing developed into a tug-of-war in which Jan more than held his own. The watches in the boxes came sliding down the board and the fur cap followed them. Jan kept on pulling until a rap on his back went through him like a stab from a knife.

It was a policeman in streaming leggings, and others had arrived with him. Jan let go of his prize, recoiling from their gaze. Yet the policeman was not looking at him. He was pointing at the fur-capped rascal, and adding to Jan’s embarrassment.

“You give this young feller what he fairly won. I saw what you did. I’ve had my eye on you all night. You give him that watch, or you’ll hear more about it!”

Jan went suddenly cowardly. He tried to say he did not want it, but his tongue would not work. The lights of the fair were going round and round him. The policeman, the rogue, and three or four more, had been joined by Mulberry, who was staring and pointing and trying to say something which nobody understood. The policeman cuffed him and pushed him away, and Jan began to breathe. He felt the watch being put into his unwilling hand. He heard a good-humoured little cheer. He saw the policeman looking at him strangely, and wondered if a tip was expected. He could only stutter his thanks, and slink from the scene like the beaten dog he felt.

Luckily his legs were in better shape than his head, and they carried him in the opposite direction to his house. He had not gone far when his mind rapidly recovered tone. It recovered more tone than it had lost. He was not only safe so far, he realised, but successful beyond his wildest dreams. Not only had he been to the fair, but thanks to the policeman he had come away with a silver watch to show for the adventure. What would they have to say to that in the little dormitory? They would never be able to keep it to themselves. It would get all round the school and make him somebody after all. He would go down in history as the fellow who got out at a moment’s notice, and went to the fair in a master’s hat and coat, and won a prize at a watch-la, and brought it back in triumph to the dormitory, at Heriot’s of all houses in the school!

He would probably tell Heriot before he left. Old Bob was just the man to laugh over such an escapade. Better still, he would laugh more heartily if one kept it till one came down as an Old Boy. Jan felt ridiculously brave again under old Bob’s umbrella, which he had dropped during the rumpus at the fair. That, of course, was why he had lost his head. But now he was bold as a lion, determined to do something at school after all, so that he could come down as an Old Boy to tell of this very adventure. Not that he was a boaster. But he was still in this abnormal mood which had only been interrupted by a minute of pure panic. The sodden pavement floated under his feet like air.

Jan never so much as heard the overtaking footsteps. A strong arm slid through his, and a voice that he heard every day addressed him in everyday tones.

“Do you mind my coming under your umbrella?”

18. Dark Horses

It was Dudley Relton, and his forearm felt like a steel girder. Yet his tone was too polite for that of a master addressing a boy, and there was nothing — no use of his surname — to tell Jan that he had been recognised. But he was far too startled to take advantage of that.

“Oh, sir!” he cried out as if in pain.

“I shouldn’t tell the whole town, if I were you. You’d better come in here and pull yourself together.”

He had put his latch-key into the side door of a shuttered shop. Over the shop were lighted windows which Jan suddenly connected with Relton’s rooms. He had been up there once or twice with extra work, and now he was made to lead the way. The sitting room was comfortably furnished, with a soft settee in front of a dying fire, and bookcases on either side of it. Jan came round from a nightmare vision of the certain outcome, which he had never fully realised until now, to find himself on the settee. He sat gazing at the muddy boots of Dudley Relton, who had poked the fire before standing up with his back to it.

“Of course you know what is practically bound to happen to you, Rutter. Still, in case there’s anything you’d like me to say in reporting the matter, I thought I’d give you the opportunity of speaking to me first. I don’t honestly suppose that it can make much difference. But you’re in my form, and I’m naturally sorry that you should have made such a fatal fool of yourself.”

The young man did indeed sound sorry. That was just like him. He had always been decent to Jan, and he was sorry because he knew that it was all over with a fellow who was caught getting out at night. Of course it was all over, so what was the good of saying anything? Jan kept an eye on those muddy boots, and answered never a word.

“I suppose you got out for the sake of getting out, and of saying you’d been to the fair? I don’t suppose there was anything worse behind it. But I’m afraid that’s quite bad enough, Rutter.”

And Relton heaved an unmistakable sigh. It had the effect of breaking down the silence which was Jan’s refuge in any trouble. He mumbled something about ‘a lark,’ and Relton took him up quite eagerly.

“I know that! I saw you at the fair — spotted you in a moment as I was passing — but I wasn’t going to make a scene for all the town to talk about. I can say what I saw you doing. But I’m afraid it won’t make much difference. It’s a final offence at any school, to go and get out at night.”

Jan thought he heard another sigh, but he had nothing more to say. He was comparing the two pairs of boots under his downcast eyes. His own were the cleaner, still with the boot-boy’s shine on them amid splashes of mud and blots of rain. They took him back to the little dormitory at the top of Heriot’s house.

“Why did you want to do it?” cried Relton with sudden exasperation. “Did you think it was going to make a hero of you in the eyes of the school?”

Jan hung his head lower still, as if confessing it.

“You! You who might really have been a bit of a hero, if only you’d waited till next term!”

Jan looked up at last. “Next term, sir?”

“Yes, next term, as a left-hand bowler! I saw you bowl last year, the only time you ever played on the Upper. It was too late then, but I meant to make something of you this season. You were my dark horse, Rutter. I had my eye on you for the Eleven, and you go and do a rotten thing, for which you’ll have to go as sure as you’re sitting there!”

So that was behind all those kind words and light penalties. The Eleven itself! Jan had not been so long at school without discovering that the most heroic of all distinctions was membership of the school Eleven. Once or twice he had dreamt of it as an ultimate possibility, but even Chips had regarded it as only a distant goal. And to think that it might have been next term, just when there was to be no next term at all!

“Don’t make it worse than it is, sir,” mumbled Jan as the firelight played on the two pairs of drying boots. Relton shifted impatiently on the hearthrug.

“I couldn’t. It’s as bad as bad can be. I’m only considering if it’s possible to make it the least bit better. If I could get you off with the biggest licking you’ve ever had in your life, I’d do so whether you liked it or not. But what can I do except speak to Mr Heriot? And what can he do except report it to the Headmaster? And do you think Mr Thrale’s the man to let a fellow off because he happens to be a bit of a left-hand bowler? I don’t, I tell you frankly. I’ll say and do all I can for you, Rutter, but it would be folly to pretend that it can make much difference.”

Jan never forgot that angry, reproachful, yet not unsympathetic look on a face which was not much less boyish than his own. He liked Dudley Relton more than ever, and felt that Dudley Relton had a sneaking fondness for him, quite apart from his promise as a bowler. But that only poured salt on the wound, smeared bitter irony on his inevitable fate. Here was a friend who would have made all the difference to his school life, fanning his little spark of talent into a famous flame. It was a tragedy, and of his own making.

They marched back together, once more under Heriot’s umbrella, to the house and to Heriot himself, with his flashing spectacles and annihilating rage. The merry-go-round was silent at last. In the emptying market place the work of dismantling the fair was beginning, even as the church clock struck twelve. Stalls were being cleared and half the lights were already out. But ground-floor lights were still on in Heriot’s, and the front door was still unlocked. Relton opened it softly, and shut it with equal care behind the quaking boy.

“You’d better take those things off and hang them up,” he whispered. So he had recognised Heriot’s clothes, but had thought that impertinence a detail compared with the major crime. Jan himself had forgotten it, but took the hint with trembling hands.

“Now slip up to the dormitory and hold your tongue. That’s essential. I’ll say what I can for you, but the less you talk the better.”

Jan understood that. He was the last person to confide in anybody if he could help it. But there were three fellows in the secret of his escapade, all three doubtless lying awake to hear of its outcome. It would be impossible not to talk to them. But he must use the fewest possible words. Jan groped his way to the lead-lined stairs. The lower dormitories were still, and in the utter silence he heard Heriot’s voice raised in startled greeting on his side of the house. Jan shivered as he sat down on a step to take off his boots. Was it any good taking them off? Would not the green baize door burst open and Heriot be upon him before the first lace was undone? But no Heriot appeared, and Jan crept up, dangling his boots.

The small dormitory was as still as the other two. Jan could not believe that his comrades had fallen asleep, as it were at their posts, and felt irritated. Then came simultaneous whispers from opposite corners.

“Is that you, Tiger?”

“You old caution! I wouldn’t have believed it of you.”

“You didn’t know him as well as I did.”

“I’m proud to know him now, though. Shake hands across the tish!”

“Thank goodness you’re back!”

“But how did you get back?”

“Same way as I got out,” muttered Jan at last. “Are you all three awake?”

“All but young Eaton. Eaton!”

No answer from the new boy’s corner.

“He’s a pretty cool hand” — from Bingley.

“But he’s taken his dying oath not to tell a soul” — from Chips.

“He won’t have to keep it long, then.” Jan was creeping into bed.

“Why not?”

“I’ve gone and got cobbed.”

“You haven’t!”

“Afraid so.”

“Oh, Tiger!”

“But you’re back, man!”

“I was seen first. I’m certain I was. It’s no use talking about it now. You’ll all know soon enough. I’ve been a fool. I deserve all I’m bound to get.”

“I was a worse fool!” gasped Bingley over the partition. “I dared you do what I wouldn’t have done myself for a hundred pounds. But I never thought you would, either. I thought you were only hustling. I swear I did, Tiger!”

Bingley was in real distress. Chips combined sore anxiety with a curiosity which Jan might have satisfied, had it not been for Relton’s parting advice. It crossed Jan’s mind that Relton, in giving that advice, might have been thinking of himself: he might not wish it known that he had taken Jan to his own rooms before hauling him back to Heriot’s. Jan would keep his mouth shut, in gratitude for the one redeeming feature of the whole miserable affair.

Miserable it was, and, now that it had so unexpectedly opened his eyes, utterly humiliating. He had boasted that he didn’t care if he were expelled. That was not altogether a boyish idle boast. He had meant it, more rather than less. His whole school life had seemed a failure, and his old hatred of it had been revived. Bingley’s provocation had merely been a spark on existing tinder. Because he had seen no prospect of creditable notoriety, discreditable notoriety had appealed to his aching young ambition. The fact that he had ambitions at all might have shown him that school meant more to him than to the many who, like Bingley, complacently accepted a humdrum lot. But Jan was not naturally introspective and, like other healthy young minds forced into introspection, he misunderstood himself in many ways. The escapade had seemed glorious, the prospect of expulsion fine. But now that the prospect had become reality, he saw how inglorious it all was. He saw, too late, the real glory that might have been his, at the school he had pretended to despise.

But that had been a pose. He had never despised it in his heart. He knew that now. He had begun by hating it as a wild creature hates captivity. He had loathed it as a place where an awkward manner and a marked accent exposed one to ridicule. But even in the days of hatred and of loathing, when his chief satisfaction had been to damp the ardour of an enthusiast like old Chips, Jan had been conscious of a sneaking veneration for the machine into which he had been thrust. The ruling impulse of his heart had been to do as well as other fellows, to show them that he was as good as they were, even if he lacked their manners and their speech. He knew that now.

He could trace it back to his first arrival, to the football which was stopped, to the paper-chase which he had run in spite of them, and then to last year’s Mile and the cricket which was also stopped. How much had been against him! Yet how little had he suspected his own strongest point! Only to think that he might have bowled for the school this coming season! Relton should have kept that to himself. He had talked about making things better, but had only made them worse to bear. He need not have said that. It was enough to drive a fellow mad, with the thought of all he was losing through his criminal folly.

Individuals filled the stage of Jan’s cruel visions. Evan Devereux in the limelight: what would he have said if Jan had got into the Eleven? Might it not have brought them together again? Evan had got into the lowest Upper team, having been in the highest Lower one the term before Jan came, and Jan had been left out of even the lowest team on the Middle Ground, which Evan had skipped altogether. It would have been a case of the hare and the tortoise, but in the end they might both have been in the Eleven together, and then they could scarcely have failed to be friends. So simply and so yearningly did Jan think of the fellow with whom he now seldom exchanged as much as a nod. But he was nevertheless the one to whom Jan owed more than the whole school put together, for had he not kept something right loyally to himself?

Then there was old Haigh. He would have seen there was something after all in a fellow who could not write Latin verses, something in even a sulky fellow. And Jan no longer sulked as he used to; he was getting out of that. And yet he had done this thing, and would have to go ...

Then there was Shockley and all that lot, the rotten element in the house. If he had really got into the Eleven, it would have made all the difference in the world between Jan and them. They never touched him now, but their words were worse than blows, and far more difficult to return. But if Jan had got into the Eleven ...

And there was Chips. He had robbed his prophet of the vindication of a lifetime. For Jan to have made the Eleven would have been a greater victory to that unselfish soul than making the Middle himself. And Relton spoke as if he really would have had a chance, but for this thing that he had done!

He lay in his bed and groaned aloud, and found himself listening for an answering movement from one of the others. He could have opened out to them now, to any one of them, but they were all evidently fast asleep. The church clock had struck two some time ago, and Jan was still poignantly awake. He had not lain awake like this since his very first night in the school, and in this same tish. And now it was his last!

Tomorrow night he would be back in the rectory attic where he was less at home than here, and back under the blackest cloud of his boyhood. That was saying something. Term-time was still preferable to the holidays, except when he went to stay with Chips and see some of the sights of London. And now it was his last night of his last term, unless a miracle saved him ...

And now it was his last morning, and Jan felt another creature, because he had slept like a top after all, and the wild adventure of the night was no longer the sharp reality which had kept him awake so long. It was more like a dream which might or might not have happened. If it had happened, why were Chips and Bingley washing and dressing without a word about it? Jan forgot about young Eaton in the fourth tish, but at the back of his muddled mind he knew well enough that it was no dream, even before his muddied boots gave him the final proof. Yet he rushed downstairs as the last bell was ringing, flew along the street without a bite of dog-rock or a drop of milk, and hurled himself through the schoolroom door as the polly of the week was about to shut it in his face. As though it still mattered whether he was late or not!

He thought of that while he recovered his breath during the psalms. Throughout the prayers he could only think of the awful voice reading them, and whether it would pronounce his doom before the whole school, and whether it would not be more awful in private. Jan watched the pale old face, laden with another day’s stock of stern care. And he wondered whether his beggarly case would add a flash to those austere eyes, or a passing furrow to that formidable brow.

Jan could not see Heriot’s face, but his shoulders looked relentless, and from the pose of his head it was certain that his beard was sticking out. There was no catching Heriot’s eye after prayers, and even young Relton, at first school, looked as though nothing had happened overnight. He took his form in Greek history with that rather perfunctory air which marked all his work in school. But so far from ignoring Jan, or showing him any special consideration, Relton was down on him twice for inattention, and the second time he ordered him to stay behind the rest. Jan did so, and was not called up until the last of the others had left.

“I didn’t keep you back for inattention,” explained young Relton calmly. “I could hardly expect you to attend this morning. I kept you back to tell you of my conversation with Mr Heriot last night.”

“Thank you, sir.”

“I began by sounding him out on the punishment for getting out at night — even on the pretext of a lark — in which I was prepared to corroborate your statement as far as possible.”

Dudley Relton was already falling into the schoolmaster’s trick of literary language, and here was at least one word of which Jan did not know the meaning. But he said “thank you” again. Relton gathered his books together with some care before continuing.

“It’s perfectly plain from what he says that the one and only punishment is — the sack!”

Jan said nothing. Neither did he wince. He was prepared for the blow, and from Dudley Relton he could take it like a man.

“That being so, Rutter,” continued Relton, stepping down from his desk, “I said nothing about last night.”

This was far harder to hear unmoved.

“You said nothing about it?” Jan even forgot to say “sir.”

“Please don’t raise your voice, Rutter.”

“But — sir! Do you mean you never told Mr Heriot at all?”

“I do. I went in to tell him, but I soon saw it meant the end of you. So I said nothing about you after all. You’ll kindly return the compliment, Rutter, or it will mean the end of me!”

It was Jan who first broke into a smothered jumble of thanks, expostulations, and solemn vows. There were only three fellows who knew he had got out, but even they did not know that he had actually encountered any master, and they never would. His gratitude was less coherent, but his anxiety on Mr Relton’s behalf was so great that even that unconventional master had to laugh.

“We’re in each other’s hands, Rutter, and perhaps my motives were not so pure as you think. Remember that you’re my dark horse. Run like a good ’un, and you’ll soon be even with me. But never run amuck again as you did last night!”

“I never will, sir. That I’ll swear.”

“I don’t only mean to that extent. I saw a pipe in your mouth before the row. You weren’t actually smoking, but I fancy you do.”

“I have done, sir,” said Jan, without going into detail.

“Well, give it up. If you want to do something for me, don’t go smoking again while you’re here. It’s bad for your eye and worse for your hand, and a bowler has need of both. Run straight as a die, Rutter, and let’s hope you’ll bowl as straight as you run!”

19. Fame and fortune

There was really only one bowler in that year’s Eleven, and Chips Carpenter was his prophet. There were others who took turns at the other end, who even captured a few wickets between them; but ‘the mainstay of our attack was Rutter,’ as the Magazine found more than one occasion to remark. The Magazine displayed a marked belief in the new bowler, from his very first appearance with his lowly black school cap pulled down behind his prominent ears. Its rather too pointed phrases were widely attributed to the new editor, who was none other than Crabtree, now a polly and captain of Heriot’s house. The fact was, however, that Crabtree employed Chips as cricket correspondent, though he had to edit him severely, especially in those remarks which found disfavour in other houses.

Old Crabtree, who had suddenly grown into a young man, made by far the best captain the house ever had in Jan’s time. But he was a terrible martinet. You had to shut yourself up in your study to breathe the mildest expletive, and it cost you sixpence to throw the smallest stone in the quad. Crabtree was not precisely popular, but he was respected for his scornful courage and his caustic tongue. He ruled by dint of personality unaided by athletic prowess, and during his four terms of authority there can have been few better houses than Heriot’s in any school. Shockley likened it to a nunnery without the nuns, and left in disgust for reasons best known to himself. Buggins and the portly Eyre grew into harmless and even useful members of the community. And the fluent and versatile Chips learnt a lesson or two for the rest of his literary life.

“I wish you’d use people’s names, instead of saying ‘the latter’ and ‘the former’,” said Crabtree, coming into Chips’s study with a proof. “And look here! I’m blowed if I have ‘The Promise of May’ dragged in just because we happen to have lost a match in June! And we won’t butter Rutter more than twice in four lines, if you don’t mind, Chips.”

But Crabtree was not cricketer enough to distinguish the quality of the butter from its quantity, and some sad samples escaped detection. ‘Rutter took out his bat for a steadily-played five,’ for instance, and ‘the third ball — a beauty — bowled Rutter for a well-earned eight.’ They were certainly Jan’s largest scores for the team, for he was no batsman, but even on firmer ground the biased historian went much too far. ‘Better bowling than Rutter’s would be hard to imagine. Many of his deliveries were simply unplayable.’ Jan really had taken six wickets, but at considerable cost. And this report concluded: ‘At the end of the first day’s play I. T. Rutter received his First XI colours which, needless to say, were thoroughly well merited.’

Jan’s best performance, however, was against the Old Boys on Founder’s Day. Repton and Haileybury Schools it was good to meet and better to defeat. But the Old Boys’ Match was the most popular feature of the chief festival of the school year. It inspired the rising generation with a glimpse of famous forerunners, and gave the forerunners the chance to judge their successors. This year the Old Boys came down in force. There was Boots Ommaney who, despite being a Cambridge don, had played for England at both ends of the earth. There was A. G. Swallow, for some seasons the best bowler and still the finest all-round player the school had ever turned out. There was the ever-cheerful Swiller Wilman, younger and less exalted, who nevertheless compiled an almost annual century in the match. In all there were six former Captains of the Eleven and four old university Blues. But Jan had seven of their wickets in the first innings — five of them clean bowled — on a wicket a shade less than fast.

“Well done again!” said Dudley Relton in the pavilion. “Don’t be disappointed if you don’t do so well next innings, or even next year. But on that wicket you might run through the best side in England — for the first time of asking.”

“It’s the break that does it,” replied Jan modestly, “and I don’t even know how I put it on.”

“Most left handers bowl leg-breaks. Batsmen expect it. You bowl off-breaks, which are unexpected. But they’re easier to play, once they’re ready for them. If only you had ’em both, there’d be no holding you. You’re coming to the Conversazione, of course.”

“I don’t think so, sir.” Jan was blushing furiously.

“But you’ve got your colours, and all the team came last year. It’s school songs from the choir, and ices and things for all hands, you know.”

“I know, sir.”

“Then why aren’t you coming?”

Jan looked left and right to make sure that nobody could hear. “I haven’t got a dress suit,” he whispered bitterly. “That’s why, sir!”

“What infernal luck! We’re much the same build, though, aren’t we? Would you let me see if I can fix you up, Jan?”

Had it been possible to strengthen the existing bond between man and boy, those words would have done so. But it was the last of those words that meant most to Jan, for it was the first time that Relton had called him by his Christian name. The Eleven traditionally went by theirs among their peers, but as yet the Eleven had not exactly treated Jan as one of themselves. He was younger than any of them, and lower in the school than most. In moments of excitement there was still a marked breadth to his vowels; and when he pulled his new white cap tight over his head, making his ears stick out more than ever and parting his back hair horizontally to the skin, there was sometimes a wink or a grin behind his back. That this little habit was often the prelude to a wicket was noticed not only by the fielding side, but by many of the spectators on the rugs.

‘Don’t hustle,’ you would hear some fellow say. ‘The Tiger’s got his cap pulled down, and I want to watch.’

Chips had never had so much material for his poetising (‘The bowler came down like a wolf on the fold’) and Jan, on whom he tried it all out, listened as usual with tolerance and amusement.

“Cricket’s your religion, isn’t it, Chips?” he remarked one day. ”And these are your hymns.”

Chips was much struck. “That’s a ripping idea, Tiger! There’s any amount of raw material there!”

He seized a bit of paper and scribbled. “What about this?

Abide with me; fast fall the wickets and

The time has come to make a final stand.

When other batsmen fail and hope’s all gone,

Tail-end left-hander, save the follow-on!

Well, it could do with a bit of polishing, but you see the possibilities.”

Jan had winced both at the words and at Chips’s attempt at singing. “Hmm. Crabtree’d never accept things like that — he’d smell blasphemy. I don’t think you could use hymns.”

Chips was a little dashed. “I suppose not. All right, not hymns, then. Still, you’re right. Cricket is a sacred subject, and sacred subjects need sacred poems.”

That was a halcyon term for Jan, and to crown it all he was still in Dudley Relton’s form. There he was treated with cynical indulgence, for Relton’s job was to uphold the cricketing tradition, and he would not have upset his best bowler even if there had been no other tie between them. That other tie was never mentioned, but thinking of it sweetened the bowler’s triumph.

Heriot, moreover, was delighted to see a colleague giving Jan the encouragement which delicate circumstances prevented him from giving himself. There was no jealousy or narrowness in Robert Heriot. He was a staunch champion of Relton, whose methods and temperament scarcely commended themselves to hardened masters like Haigh. But then Heriot himself was having a very good term. His house was in order under the incomparable Crabtree, and Rutter was not its only member in the Eleven. Stratten already had his colours for wicket-keeping, and Jellicoe looked certain of his as a batsman. The three provided a bit of the best of everything for the house eleven, which was already carrying all before it in the All Ages competition. Haigh had not spoken to Heriot for two whole days after his own house went down before ‘the most obstinate blockhead that ever cumbered my hall.’

Jan enjoyed that match, like all his triumphs, but it was not his nature to show it. Chips made up for him. He not only penned his sacred poems singing Jan’s praises in print, but talked about him by the hour, so much so during the match in question that Haigh told him straight that he was ‘behaving like a private-school cad.’ Heriot, on the other hand, had never thought so highly of Chips, for he knew what he would have given to be a practical player instead of a mere enthusiast. And Heriot liked Jan no less for sticking to his first friend. He wished he could overhear their Sunday evening chats, which still took place in the immaculate museum of Chips’s study, the only one of the two fit to sit in. Jan was still indifferent to his surroundings. His walls were still innocent of pictures, grease-spots had multiplied on Shockley’s green tablecloth, and the papers on the floor were now transparent with blots of oil from his bat.

“I hope you’re keeping the scores of all your matches,” said Chips one night. “You ought to stick ’em in a book. If you won’t, I’ll do it for you.”

“What’s the good?”

“Good? Well, for one thing, it’ll be jolly interesting for your kids some day.”

Chips had not smiled, but Jan grinned from ear to ear. He was feeling indolent and content.

“Steady on! It’s just like you to look a hundred years ahead.” He did not add that he was unlikely to have kids.

“Well, but surely your people would take an interest in them?”

“My people!”

Chips knew it was a sore subject. “But surely they’re jolly proud of your being in the Eleven?”

“My uncle might be. But he’s in India.”

“And I suppose the old people don’t know what it means?”

“They might. I haven’t told them.”

Chips could hardly believe his ears. But he could not comment on that revelation, so he shifted back to where he had started.

“You’ll bowl for the Gentlemen before you’ve done. And then you’ll be sorry you haven’t got the first chapter in black and white. You should see the book A. G. Swallow keeps! I saw it once when he visited my private school. He’s even got his leave to be in the Eleven, signed by Jerry. If I were you I’d have yours in a frame!”

Nobody could obtain his Eleven or Fifteen colours without a permit signed by house-master and form master and finally endorsed by Mr Thrale himself, whose signature was seldom added without a cordial word of congratulation.

“I believe I have got that, somewhere or other.”

Chips eventually found it among the Greek and Latin litter on the floor.

“What a chap you are! I’m going to keep this for you until one or other of us leaves, Tiger. You’re — well, I can’t say you’re not fit to be in the Eleven, but I’m blowed if you deserve to own a precious document like this!”

Yet there was another document which Jan already had under lock and key, except when he took it out to read once more. Chips never saw or heard of this one, but he would have recognised the writing at a glance, and Jan knew what sort of glance it would have been. This was what it said:

The Lodge

1st June

Dear old Jan,

I can never tell you how I rejoice at your tremendous success. Heaps of congratulations! I’m proud of you, so will they all be at home. School is awful for dividing old friends unless you’re in the same house or form. You know that’s all it is or ever was! Will you forgive me and come for a walk after second chapel on Sunday?

Always your old friend,

Evan

Chips knew nothing until the Sunday, when he said he supposed Jan was coming out after second chapel as usual, and Jan replied very off-hand that he was awfully sorry, he was engaged. “One of the Eleven, I suppose?” said Chips, not in the least inclined to grudge him to them. Then Jan told the truth aggressively, and Chips made a tactless comment, and Jan told him he could get somebody else to sit in his study that night. It was the first break in an arrangement which had lasted since their first term.

In the event, Jan enjoyed the afternoon walk and talk more than any since the affair of the haunted house a year before. It was just as well that Chips had been left out. He would not have found Evan Devereux improved; indeed he saw quite enough of him in school to be convinced of that already. They never fraternised in the least, and it is in his intimate moments that a boy is at his worst or best.

Evan was immediately as intimate with Jan as though they had been at different schools for the past year. Outside the chapel he took Jan’s arm, at which Jan rejoiced, and off they went like old bosoms. Evan seemed a good deal more than a year older. His voice had settled into a rich tenor and his reddish hair was crisper and perhaps less red. But he was still short for his age, and acquiring the cock-sparrow strut of some short men. His conversation strutted deliciously. It would have made Chips grind his teeth. Of course it was cricket conversation, but Evan soon turned it to his own cricket, and Jan followed him in all humility. Evan had been a bit of a batsman all his life. The stable lad, who in the old days had usually been able to bowl him out at will, had always wished that he could bat as well. He said so now, and Evan, who was going to get into the third eleven with luck, was full of sympathy with the best bowler in the school.

“It must be beastly always going in last. I expect you’re jolly glad when you don’t get a ball. But at least you don’t have to walk back alone!”

“I’m always afraid I may have to go in when a few runs are wanted to win the match, and a good bat well set at the other end. That’s the only thing I should mind.”

“You remember the Pinchington ground?” asked Evan abruptly, as though he had not been listening.

“I do that!” cried Jan, and Evan looked round at him. Jan remembered how he had longed, when as small boys they played village cricket there, to be in flannels like Master Evan instead of his Sunday shirt and trousers. Evan was thinking that the school bowler had spoken exactly like the stable lad.

They reminisced about past cricket for a while, and then moved to present cricket. But Jan, who always preferred doing a thing to talking about it, and who wanted to know a lot of things that he did not like to ask, tried to change the subject. He tried the horses, and was sorry and embarrassed to hear that the stables had been reduced. He tried the Miss Christies. But cricket was the only talk that Evan would sustain. As they wandered back towards the thin church spire with the golden cock atop, looking rather like an inverted exclamation mark on a sheet of pale blue paper, it was made clear to Jan that he was not to regard himself as the only cricketer. But he had no desire to do so, and he could not have been heartier in his agreement.

“You’ll get your colours next year, Evan, and then we’ll be in the same game every day of our lives!”

“I have my hopes, I must say. But it’s not so easy to get in as a bat.”

“No. You may get a trial and not come off, but a bowler’s bound to if he’s any good. Anyhow, you’re in a jolly strong house, and that’s always a help.”

“We ought to be in the final this year,” said Evan thoughtfully.

“And so ought we.”

They were both right, and the last match of the term on the Upper, on the last Saturday, was the decisive one between their two houses. A few days beforehand Evan told Jan that his people were coming down to see it. Jan could not conceal his nervousness at that prospect. But it left him more determined than ever that Heriot’s should have the cup. He had some new flannels specially made at the last moment, and had his hair cut the day before the match. As he took the ball and pulled his cap down further than ever, it gashed his back hair the more conspicuously to the scalp.

In the event, his bowling was on form. True, variety was lacking, and a first-class batsman would have taken its measure in about an over. But there were scarcely the makings of one in the Lodge team, and great was the fall of that house. Heriot’s won a low-scoring match by an innings in the course of an afternoon. Jan had fifteen wickets in all, including Evan’s twice over. The first time, when he was caught in the slips, Evan’s nought might be counted as hard luck. But in the second innings it was a complex moment for Jan when Evan strutted in with the air of a saviour of situations. Jan did not want him to fail again, and yet he did because Evan’s people were looking on. He felt mean and yet exalted as he led off with a trimmer, and the leg bail hit Stratten in the face.

“I’m awfully sorry!” he stammered tactlessly, but Evan passed him flaming, without a sign of having heard.

Mr Devereux, however, could afford to treat the whole affair differently. He was a florid and fine-looking man with a light grey bowler, a flower in his coat, and all the boisterous self-confidence proper to a successful ironmaster. He was far from grudging Jan his success. On the contrary, he seemed only too ready to transfer his paternal pride to his old coachman’s son, and was sorely tempted to boast of him as such. Some saving sense of fitness, assisted by a quiet hint from Heriot, sealed his itching lips. But in talking to Jan by himself Mr Devereux naturally saw no need for restraint.

“I remember when you used to bowl to my son in front of your father’s — ah — in front of those cottages of mine — with a solid india-rubber ball! We never thought of all this then, did we? But I congratulate you, my lad, and very glad I am to have the opportunity.”

“Thank you very much, sir,” said Jan, in a grateful glow from head to heel.

“I’ll tell them all about you down there. And some day you must come and stay with us, as a guest, you know, and play a match or two for Evan and his friends at Pinchington. You’ll be one too many for the village lads. Quite a hero, you’ll find yourself!”

Jan was not sure what to say to that, and could only be grateful again when Mr Devereux slipped a sovereign into his hand. It was the first whole sovereign that he had been given in all his life.

But whatever Jan’s gratitude to Devereux senior, his bitterness over Devereux junior had been reviving ever since their walk together. Evan turned his charm on and off as he chose, now fanning the flames, now damping them down; aware, surely, that he was playing with the flames of friendship, but unaware that they were flames of something more. And ever since that walk, when his place had been usurped by Evan, Chips had been quite unusually aloof and distant. Jan found himself even more sorry about that than about Evan’s blowing hot and cold. The evening of the day after the All Ages final he went, as he always had done until things turned sour, to sit in Chips’s study as if nothing had happened, and silly old Chips nearly wept with delight. But nothing was said about the few weeks of sourness.

20. The eve of office

Thenceforward Jan’s career was that of the cricketer who made no indelible mark as anything else. Like other people, he had his ordinary life to lead. Like them, he had to rush out every day to early school. In form, he had to work harder than most to keep afloat. ‘Solid work in the bullies,’ as the Magazine put it, eventually landed him in the Fifteen. But there was less glory there than in the Eleven, for the school was still playing its own age-old brand of football — although there was already talk of adopting the Rugby rules — and apart from the Old Boys’ Match no outside fixtures were possible. And Jan was placed more than once in the Mile and the Steeplechase without winning either. None of these were his strong points, though he took them seriously at the time. They kept him fit during the winter, but it was not they that made his name. Some of his bowling analyses, on the other hand, were as unforgettable as the date of the Norman Conquest, and were instantly and equally imprinted on every mind in the school. So too was the image of him on the Upper, with his Eleven cap pulled down over his eyes and a grim twinkle under the peak.

His second year in the Eleven was nearly — not quite — as successful as his first. He took even more Haileybury and Repton wickets, but experienced batsmen in other teams sometimes made almost light of that clockwork off-break of his. The cheery Swiller Wilman (who owed his nickname to his notorious teetotalism) again compiled his usual century for the Old Boys. It was a hotter summer, and the wickets a trifle faster than those after Jan’s own heart. Still, he had a fine season and a marvellously happy one. He was now somebody in the Eleven, not a mere upstart bowler of no previous standing, not a fish out of water. Bruce, the new captain, was a good fellow who not only always gave Jan the choice of ends and an absolute say in the placing of his field, but took his best bowler’s advice on all sorts of points. Jan found himself in a position of high authority without the cares of office, and the day came when he appreciated the distinction.

Stretton and Jellicoe were in the team for their second and last year, and the All Ages cup remained undisturbed on the baize shelf in Heriot’s hall. Crabtree, moreover, was still the captain of a house in which his word was martial law. But he too was leaving. All the bigwigs were, except Jan himself. After the holidays Heriot had to face a younger house than for some years past, with a colourless polly in command till Christmas, and only old Chips to succeed him.

Chips was now a polly himself, being actually in the Upper Sixth, and he now edited the precious Magazine to which he had so long contributed. This gave him his own standing in the school, and he had long outgrown — or been lured out of — the priggishness of his earlier days. Not only that; his old enthusiasm was often missing too. It had been his weak patch of boyhood, which he had struck later than most. He was an ardent wicket-keeper who had incurred a flogging in his saintlier days by cutting a detention to keep wicket on the Lower, and he was still on the Lower, though he thought he ought to have been in one of the Middle teams. In the winter months, with his new Lillywhite usually concealed about his person, he used to dream of runs from his own unhandy bat. But he knew in his heart that his only place in the game was as student and trumpeter of glories beyond his grasp. He was frank about it in his lament for the examinations he had failed properly to revise for.

But ’tis no use lamenting. What is done

You couldn’t undo if you tried.

Oh, if only they’d set us some Wisden,

Or Lillywhite’s Guide!

Many fellows liked old Chips nowadays and even took a charitable view of his writings, but few would have picked him out as a born leader of men.

Meanwhile Evan Devereux had been elected Captain of Games, a most important officer in the Easter term, the games in question being nothing of the kind except in an Olympic sense, but just the ordinary athletic sports. The Captain of Games arranged the heats, fixed the times, acted as starter, and exercised an overall control that just suited Evan. He proved himself a born master of ceremonies, with a jealous eye for detail, but a little apt to fuss and strut. He dressed well, and had a pointed way of taking off his hat to the masters’ ladies. There were those, of course, who crudely described his mannerisms as mere roll; but on the whole it would have been hard to find a keener or more capable Captain of Games.

The office was usually held by a member of the Eleven or the Fifteen. Evan was in neither, though on the edge of both. On the other hand, he was a polly and high in the Upper Sixth, having lost neither his flair for acquiring knowledge nor his inveterate horror of incurring rebuke. It is at first sight a little odd that such a blameless boy should ever have made the bosom friend he did. Sandham was a big fellow low down in the school and in another house, but a handsome daredevil of strong but questionable character, whom it suited to have a leading polly for his friend.

One hesitates to add, in case it is thought that this accounted for Evan’s side of the friendship, that Sandham was the younger son of a rather prominent peer. He was not the only fellow whose parentage was marked in the school list by the curious prefix of ‘Mr.’ But the others were nobodies, and Evan did not make up to them. Yet in the aristocracy of sport he could bow as low as the next boy, and Sandham was an athlete of the first water — in the Fifteen and the Eleven, and winner of the Steeplechase, Hurdles, Hundred Yards, Quarter Mile and Wide Jump. He became Athletic Champion by a large margin, and wore his halo with a rakish indifference which lent colour to the report that ‘Mr’ Sandham had already been bunked from Eton before old Thrale gave him another chance.

“He’s a marvellous athlete, whatever else he is,” said Chips to Jan on the last Sunday of the Easter term.

“I’m blowed if I know what else he is,” replied Jan. “But I wouldn’t see quite so much of him if I were Evan.”

“If you were Evan, you’d jolly well see all you could of anybody at the top of the tree!”

“Look, Chips, dry up! Evan’s pretty near the top himself.”

“Are you going to stick him in the Eleven?”

“If he’s good enough, and I hope he will be.”

“Of course it’s expected of you.”

“Who expects it?”

“Sandham for one. And Devereux himself for another. Look how they stopped to make up to you when they overtook us just now!”

Two faults which Chips still retained were touchiness and jealousy, especially where Jan was concerned. As for Jan, if he had been on brink of Evan’s friendship last summer, Sandham had usurped his place; but Jan still could — still had to — rise to Evan’s defence.

“I don’t know what you mean. Evan’s a friend of mine, and of course I’ve seen a lot of Sandham. They only asked if I was going to get any practice in the holidays.”

“They took good care to let you know they were going to have some. So Evan’s going to stay with Sandham’s people, is he?”

“So Sandham said.”

“And they’re going to have a professional down from Lord’s!”

“Well, they might be worse employed.”

“So they might. But I’d rather like to know what they’re up to this very minute.”

They were on one of the undulating country roads that radiated from the little town like tentacles — the Binchester road, as it happened, a mile past Castle Hill — and were strolling lazily between the jewelled hedgerows of early April. They had now caught a fresh sight of Evan and Sandham on the skyline, climbing a gate into the fields that led down to Bardney Wood.

Jan stopped. “I votes we go some other way. I don’t like spying on chaps, even if it’s only a case of a cigarette.” That was not wholly true, for he had had no qualms about watching those boys at Castle Hill eighteen months before. But this was an entirely different matter.

So another way they went, their conversation killed stone dead as both thought back to those events at Castle Hill. Two boys in a wood then — two of Evan’s bosoms. Two boys heading for a wood now — Evan and his current bosom. Jan’s mind recoiled from the similarities. As if his mind were on bosoms too, Chips suddenly ran his arm through Jan’s, and for once Jan allowed it to stay there.

“Isn’t it beastly to be so near the end of our time, Tiger?” Chips was determined to move to a new subject. “Only one more term!”

“It is a bit,” agreed Jan lukewarmly, as he pulled himself together. “I know you feel it, but I sometimes think I’d have done better to leave a year ago.”

Chips looked round at him as they walked.

“And you Captain of Cricket!”

“That’s why,” said Jan in the grim old way.

“But, my dear chap, it’s by far the biggest honour you can possibly have!”

“I know all that, Chipsy. But there’s a good deal more in it than honour and glory. There’s any amount to do. You’re responsible for all sorts of things. Bruce used to tell me last year. It isn’t only writing out the order, nor yet changing your bowling and altering the field.”

“No. You’ve first got to catch your Eleven.”

“And not only that, but all the other teams on the Upper, and captains for both the other grounds. You’re responsible for the lot, and you’ve got to make up your mind you can’t please everybody.”

Chips said nothing. He would have loved the unexalted post of Captain of the Middle, but he had no claim to that, and evidently Jan had no intention of favouring his friends.

“One ought to know every fellow in the school by sight,” he was saying. “But I don’t know half as many as I did. Do you remember how you were always finding out fellows’ names, Chips, our first year or so? You didn’t rest till you could put a name to everybody above us in the school. But these days neither of us take much stock of the crowd below.”

“I find the house takes me all my time, and you must feel the same about the Eleven, only much more so. By Jove, I’d give all I’m ever likely to have on earth to change places with you!”

“And I’m not sure I wouldn’t change places with you. Somehow things always look different when you really get anywhere,” sighed Jan, discovering an eternal truth for himself.

“But to captain the Eleven!”

“To make a good captain. That’s the thing.”

“But you will, Jan. Look at your bowling.”

“It’s not everything. You’ve got to drive your team. It’s no good only putting your own shoulder to the wheel. And they may be a difficult team to drive.”

“Sandham may. And if Devereux —“

“Sandham’s not the only one,” interrupted Jan, who was not talking gloomily, but only frankly as he felt. “There’s Goose and Ibbotson — who are in already — and Chilton who’s bound to get in. A regular gang of them, and I’m not in the gang, and never was.”

“But you’re in another class, Jan!” argued Chips, forgetting himself entirely in the affectionate concern for a friend which was his finest point. “You’re one of the very best bowlers there ever was in the school.”

“I may have been. I’m not now. But I might be again if I could get that leg-break.”

“You shall practice it every day on our lawn when you come to us these holidays.”

“Thanks, old chap. Everybody says it’s what I want. That uncle of mine said so the very first match we played together, when he was home again last year.”

“Well, he ought to know.”

The conversation turned into a highly technical discussion in which puny Chips, who would never get into any eleven, held his own and more. The strange fact was that he still knew more about cricket than the captain of the school team. At heart, indeed, he was the more complete cricketer of the two, for Jan was just a natural left-hand bowler, only too well aware of his limitations, and in some danger of losing his gift by laboriously cultivating a quite different knack which was not his by nature.

If only Jan himself could bowl better than ever, or even up to his first year’s form, then he would carry the whole side to victory on his shoulders. If only he could overcome his current problem. The trouble had begun about the time of the last Old Boys’ Match, when Jan had heard more than enough of that damned break which he did not have. Egged on by Captain Ambrose in the summer holidays, he had tried it with some success in village cricket, and had thought about it all the winter. Now it was uppermost in his mind. Was he going to make the ball break both ways this season? It mattered more than the constitution of the Eleven, more than the personal relations of its members, more than Evan’s inclusion in it. Possibly it mattered more than his own muddled view, that hotchpotch of yearning and jealousy, of Evan himself.

21. Out of form

There was one great loss which the school and Jan had suffered since the previous summer. Tempted by the prospect of a free hand, unfettered by tradition, and really very lucky in his selection for the post, Dudley Relton had accepted the headmastership of a Church of England grammar school in Victoria. Already he was out there, already no doubt at work on the raw material of future Australian teams, while Jan was left sighing for the masterful support which the last two captains had rather resented. Relton was replaced not by another of his rare kind, but by the experienced captain of a purely professional county team, a fine player and a steady man, but not an inspired teacher of the game. To coach anybody in anything, it is obviously better to know a little and to be able to impart it, than to know everything except how to transmit your knowledge. George Grimwood had plenty of patience, but flew too high for his young beginners, and he naturally encouraged Jan to persevere with his leg-breaks.

Not a day of that term went by but the Captain of Cricket sighed for Dudley Relton, with his confident advice and his uncanny knowledge of the game. This was especially true in the early part of May, when trial matches had to be arranged without the support of a single outsider who knew anything about anybody’s previous form. Jan found that he knew really very little about the new men himself, and Grimwood’s idea of a trial match was that it was ‘matterless’ who played for the Eleven and who for the Best. The new captain no doubt took his duties too seriously from the first, but he had hoped for more help from the new professional. At the same time he was under a cross-fire of suggestions from the other fellows already in the team, of whom there were four. Five old hands make a fine backbone to any school eleven, but Jan wished there were only one or two offering him advice.

Old Goose, who as Captain of Football thoroughly lived up to his surname in the eyes of the masters but not at all in public opinion, would have filled half the vacancies from his own house. His friend Ibbotson, a steady bat but a most unsteady youth, had other axes to grind. Tom Buckley, a dull fellow, invariably agreed with the last view put forward. But what annoyed Jan most was the way in which, from the very first day of term, Sandham ran Evan as his candidate, pressing his claims as though other people were bent on disregarding them.

“I saw Evan play before you did, Sandham,” said Jan, bluntly, “and there’s nobody keener than me to see him come off.”

“But you didn’t see him play in the holidays. The two bowlers we had down from Lord’s thought no end of him. I don’t think you know what a fine bat Evan is.”

“Well, I’m only too ready to learn. He’s got the term before him, like all the rest of us.”

“Yes, but he’s the sort to put in early, Rutter, you take my word for it. He has more nerves in his little finger than you and I in our whole bodies.”

“I do know him,” said Jan, rather tickled at having Evan of all people explained to him.

“Then you must know that he’s not the fellow to do himself justice till he gets his colours.”

“Well, I can’t give him them till he does, can I?”

“I don’t know. You might if you’d seen him playing those professionals. And then you’re a friend of his, aren’t you, Rutter?”

“Well, I can’t give him his colours for that!“

“Nobody said you could. But you might give him a chance.”

“I might, even without you telling me, Sandham!”

And they parted company with mutual displeasure. Jan resented the suggestion that he was not going to give his own friend a fair chance, even more than the strong hint that he ought to do his friend a favour. Sandham, who had expected a rough dog like Rutter to be flattered by his advice, went about warning the others that they had for captain a Jack-in-office who wouldn’t listen to a word from any of them. There were whisperings behind Jan’s back, there were unfriendly looks, until the captain felt less a part of the Eleven that he had ever felt before.

Nevertheless Evan played in the first two matches, made 5, 0 and 1, and was not given a place against the M.C.C. Jan perhaps unwisely sent him a note of very real regret, which Evan acknowledged with a sneer when they met on the Upper.

Jan had even said in his note, in a purple patch of deplorable imprudence, that on his present form he knew he ought not to be playing himself, but that as captain he supposed it was his duty to do his best. He could not very well kick himself out, but if he could he would have given Evan his place that day.

Indeed, he had not proved worth his place in either of the first two matches. Scores were not expected of him, though he no longer went in absolutely last, but his bowling had given away any number of runs while accounting for hardly any wickets at all. Jan had lost his bowling. That was the simple truth of it. In trying to cultivate a ball which nature had never intended him to bowl, he had squandered his natural gifts of length and spin. His hand had lost its innate cunning. It is a phase in the development of every artist, but it had come upon Jan at a most unfortunate stage of his career. Moreover it had coincided with that gust of unpopularity which in itself was enough to chill the ardour of a more enthusiastic cricketer.

Jan had never professed a real enthusiasm for the game. He had been a match-winning bowler who had thoroughly enjoyed winning matches, especially when they looked as bad as lost. He could never have nursed a hopeless passion for cricket as futile old Chips did. But he still had the knack of meeting his troubles with a glow rather than a shiver, and against the M.C.C. he bowled like a lonely demon. It was a performance not to be named in the same breath as his former glories, but he did get wickets, and all of them with the old off-break. The new leg-break betrayed itself by an unconscious change of action, pitched anywhere, and went for four nearly every time. Nevertheless, in the obstinacy of that glowing heart of his, Jan still bowled the new ball once or twice an over. And the school were beaten by the M.C.C.

But there was, that term, one continual excuse for a bowler of this type. The weather was wretched, and the easy wet wicket seldom dried into a really difficult one. When it did, it was not the wicket on which Jan was most dangerous, and Chips, in almost the last of his sacred poems penned for the Magazine, could only wish —

Break, break, break,

On a dead slow pitch, O ball!

And I would that the field would butter

The catch that’s the end of all!

And the beastly balls come in —

But the trouble was that Jan’s came in so slowly on the juicy wickets that a strong back-player had leisure to put them where he liked.

Some matches were abandoned without a ball being bowled, but towards Founder’s Day there was some improvement, and to add insult to injury there had been several fine Sundays before that. On one of these, the last of a few dry days in early June, Chips and Jan did what they rarely did now, and went for a walk together. They took the same road on which Devereux and Sandham had overhauled them before the Easter holidays, but this time they went further, and leant against the fence as they looked down across a couple of great sloping meadows to Bardney Wood, packed into the valley with more fields rising beyond.

The nearest meadow was bright emerald after so much rain. The next one had already a glint of gold in the middle distance. The fields that rose beyond, over a mile away behind the dense dark wood, were neither green nor yellow but smoky blue. Yet it was the wood itself that drew their attention. It might have been a patch of dark green lichen on the venerable roof of England, and the further fields its mossy slates.

“It looks about as good a jungle as they make,” said Chips. “I should go down and practise finding my way across it, if I was thinking of going out to Australia.”

Chips looked round as he spoke, but Jan seemed not to notice the bitterness and even despair in his voice.

“It’d take you all your time. It’s more like a bit of overgrown coconut matting than anything else.”

Chips welcomed the vigorous image as a rare departure from Jan’s listlessness, but it dodged the subject he was trying to raise. He was deeply distressed by his friend’s plans for his future. The Reverend Canon Ambrose was supremely indifferent about them. Jan’s own dream of following in the footsteps of his military uncle had proved impracticable. There had long been talk of his going to Australia, to another uncle who had settled out there and ran sheep by the hundred thousand. Jan liked the letters he had read and the photographs he had seen, and felt certain he would fall on his feet, and Dudley Relton, when consulted, had written back to say that Australia was the very place for such as Jan.