Shame and Consciences

25. Interlude in the wood

Morgan the house-man, and his minion who cleaned the boots and knives, were busy and out of sight in the pantry near the hall. Yet Jan was flushed and flurried as he ran down into the empty quad and dived into the closed fly which had just pulled up outside. He leant as far back as possible. The road broadened, the town came to an end. The driver drove on phlegmatically, barely wondering why one of the young gentlemen should be faring forth alone, in his cricket flannels too, and without any luggage either. He would be going to meet his friends at Molton, likely, and bring them back to see the cricket. So he thought, until a head stuck out behind him at Burston Corner, and he was told to pull up.

“Jump down a minute, will you? I want to speak to you.”

The fly stopped in one of the great dappled shadows that trembled across the wooded road, and a bucolic face peered in.

“See here, here’s nine bob for you. I’m sorry it isn’t ten, but I’ll make it up to a pound at the end of term.”

“I’m very much obliged to you, sir, I’m sure!”

“Wait a bit. That’s only on condition you keep your mouth shut. There may be a bit more when you’ve kept it shut till the holidays.”

“You’re not going to get me into any trouble, sir?”

“Not if you hold your tongue. We’re only going round by Bardney Wood instead of to Molton, and I shan’t keep you waiting there above half an hour. It’s — it’s only a bit of a lark!”

A sinful smile grew into the crab-apple face at the window.

“I been a-watching you over them palings at bottom end o’ ground all the morning, Mr Rutter, but I didn’t see it was you just now, not at first. Lord, how you did bowl ’em down! I’ll take an’ chance it for you, sir, jiggered if I don’t!”

The fly rolled to the left of Burston church, now buried belfry-deep in the foliage of its noble avenue. It threaded the road on which Chips had encountered Evan on their first Sunday walk — there was the stile where Jan had waited in the background, against the hedge. Strange to think of Evan’s attitude then and long afterwards, and of Jan’s errand now. But lots of things were strange if you were fool enough to stop to think about them. Once committed to a definite course of action, Jan was not that sort of fool. And this was almost his first opportunity of considering seriously what to say in the coming interview, how to begin, what line to take, what tone to adopt. He would have to play it partly by ear, which was annoying. It was disconcerting, too, because the very words had come to him together with his plan. In his mind he had made short work of the noxious Mulberry. But, on second thoughts, perhaps he should not make too short work of a scoundrel with tales to tell, money or no money.

The horse was walking up the last hill. There lay the wood in its hollow, in the heavy sunlight so smoky in tint that it seemed likely any moment to burst into flames like a damp bonfire. But Jan only thought of the monster in its depths, as he marched down through the lush meadows, his pocket jingling at every other stride.

Bardney Wood was so formidable a tangle of trees and undergrowth that Jan headed straight for the only gate in the fence. It led into a broad green ride, spattered with buttercups as thick as freckles on a country face. Jan went through and peered into the sombre depths of thicket on either hand, unplumbed by a ray of sun. He had hardly penetrated a yard to one side when he became the target of a million flies which buzzed aggressively, while last year’s leaves, dry even in that wet summer, rustled at every jingling step he took. His haphazard steps twisted and turned, following the line of least resistance, and were veering back towards the ride when the bulbous nose of Mulberry appeared under his very own.

It was making music worthy of its painful size, as he lay like a log on the broad of his back, in a small open space. His battered hat lay beside him, along with a stout green cudgel newly cut. Jan had half a mind to remove this ugly weapon, for the drunkard was a man of no light build. Neither did he lie like one particularly drunk, or even very sound asleep. The flies were not allowed to batten on his bloated face. Every now and then the snoring stopped as he shook them off, and presently a pair of bloodshot eyes rested on Jan’s legs.

“So you’ve come, have you?” grunted Mulberry, and the eyes ostentatiously closed again without troubling to climb to Jan’s face.

“I have,” he said with dry emphasis. It was either too dry or not emphatic enough.

“You’re late, then, hear that? Like your cheek to be late. Now you can wait for me.”

“Not another second!” cried Jan, all his premeditated plan forgotten. Mulberry sat up, blinking.

“I thought it was Mr Devereux!”

“I know you did.”

“Have you come instead of him?”

“Looks like it, doesn’t it?”

“I don’t know you! I won’t have anything to do with you,” exclaimed Mulberry, getting to his feet with grotesque difficulty.

“Well, you certainly won’t have anything more to do with Mr Devereux,” retorted Jan. “So I’m afraid you’ll have to put up with me,” he added in a much more conciliatory voice, remembering his second thoughts on the way.

“Why? What’s happened to him?” asked Mulberry suspiciously.

“Never you mind. He can’t come. That’s good enough. But I’ve come instead — to settle up with you.”

“You have, have you?”

“On the spot. Once for all.”

Jan slapped his pocket, which rang like a money-bag. The scoundrel looked impressed, but was still suspicious about Evan.

“He was to come here yesterday, and he never did.”

“It wasn’t his fault. That’s why I’ve come today.”

“I said I’d go in and report him to Mr Thrale, if he slipped me up twice.”

“‘Blab’ was your word, Mulberry.”

“Have you seen what I wrote?”

“I’ve got it in my pocket.”

Mulberry lurched a little nearer. Jan shook his head with a grin.

“It may come in useful, Mulberry, if you ever get drunk enough to do as you threaten.”

“Useful, may it?”

If the red eyes fixed on Jan had been capable of flashing, they would have done so now. But they merely watered. Till this moment man and boy had been almost as preoccupied with the flies as with each other, keeping the little brutes at bay, Mulberry with his battered hat, Jan with his handkerchief. But at this point the sot allowed the flies to cover his hideousness like a spotted veil. It was only for seconds, yet his expressionless stare had turned suddenly expressive. That could not be the flies. Nor was it what Jan thought it was.

“I’ve seen you before, young feller!”

“You’ve had chances enough of seeing me these four years.”

“I don’t mean at school. I don’t mean at school.” Mulberry was racking his muddled wits for whatever it might be that he did mean. Jan did not have to rack his own. Already he was back at the fair, that wet and fateful night in March — but he did not intend Mulberry to join him there again.

“It’s no good trying to change the subject, Mulberry! I’ve got your letter to Mr Devereux, and you’ll hear more about it if you go making trouble at the school. If you want trouble, Mulberry, you shall have all the trouble you want, and p’r’aps we’ll give the police a bit more to make ’em happy. See? But I came to square up with you, and the sooner we get it done the better for all of us.”

Jan was at home. Something he had contracted ages ago, something that he had brought with him into the world, something of his father, was breaking through the layer of the last four years and more. It had broken through before. It had helped him to fight his earliest battles. But it had never had free play in all the intervening terms, or in the holidays between terms. This was neither home nor school. This was a bite of life as Jan would have had to swallow it if his old life had never altered. And all at once it was not a nice young gentleman but a strapping lad from the stables with whom the local ogre had to reckon.

“Come on!” said Mulberry. “Let’s see the colour o’ yer coin, an’ done with it.”

Jan gave a grin of triumph, yet knew in his heart that the tussle was still to come. If he had brought a cap with him, instead of driving out bare-headed, he would have given the peak a tug. He plunged his hand into the jingling pocket and brought out a fistful of silver of all sizes, and one or two half-sovereigns. In doing so he shifted his position and trod — but left his foot firmly planted — on that ugly cudgel just as its owner stooped to pick it up and almost overbalanced in the attempt.

“Look out, mister! That’s my little stick. I’d forgotten it was there.”

“Had you? I hadn’t.” Jan kept one eye on his money and the other on his man. “You don’t want it now, do you?”

“Not partic’ly.”

“Then attend to me. There’s your money. Not so fast!”

His fist closed. Mulberry withdrew a dirty paw.

“I thought you said it was mine, mister?”

“It will be, in good time. Have a look at it first.”

“Lot o’ little silver, ain’t it?”

“One or two bits of gold as well.”

“It may be more than it looks. Better let me count it, mister.”

“It’s been counted. That’s the amount. You sign this, and it’s yours.”

With his other hand Jan had taken from another pocket an envelope, stamped and inscribed but not as for the post, and a stylograph pen. The stamp was in the middle of the envelope. Below was the date. Above was written, in Jan’s hand and in ink:

Received in final payment for everything supplied in Bardney Wood to end of June — £2 18s. 6d.

“Sign across the stamp.”

The envelope fluttered in the drunkard’s fingers.

“Two pun’ eighteen — look here — this won’t do!” he cried less thickly than he had spoken yet. “What the devil d’you take me for? It’s close on five sovereigns that I’m owed. This is under three.”

“It’s all you’ll get, Mulberry, and it’s a damned sight more than you deserve for swindling and blackmailing. If you don’t take this you won’t get anything, except what you don’t reckon on!”

The man understood, but he was almost foaming at the mouth.

“I tell you it’s a dozen and a half this summer! Half a dozen bottles and a dozen —”

“I don’t care what it is. I know what there’s been, what you’ve charged for it, and what you’ve been paid already.” Jan thought it time for a bit of bluff. “This is all you’ll get. But you don’t touch a penny of it till you’ve signed the receipt.”

“Don’t I!” snarled Mulberry.

Without lowering his eyes or giving Jan time to lower his, he slapped the back of the upturned hand and sent the money flying in all directions. Neither looked where it fell. Mulberry was ready for a blow, but Jan never moved an eye, and scarcely a muscle.

“You’ll simply have to pick it all up again. But if you don’t sign this, Mulberry, I’m going to break every bone in your beastly body with your own infernal stick.”

Jan had spoken quietly, and it must have been his face that said still more, or his long and lissom body, or his cricketer’s wrists. Whatever the medium, the message was understood, and twitching hands were held out in submission. Jan put the pen in one, the prepared receipt in the other, and Mulberry turned a back bowed with defeat. Close behind him grew a stunted old oak, forked like a catapult, with ivy winding up the stems. Down sat Mulberry in the fork, with so little difficulty that Jan might have seen it was a favourite seat, and the whole open space, with its rustling carpet and its whispering roof, its acorns and its cigar ends, an old haunt of others besides Mulberry. But he kept a close an eye on his man. The receipt was being signed, on one corduroy knee, before Jan looked up to see the broad body of a third party enclosed in the same oak frame.

It was Mr Haigh, and redder than Mulberry himself. It was Haigh with a limp collar and a streaming face. So he had smelt a rat, he had kept a watch — so like him — and he had followed the fly on foot — like the old athlete that he was! Jan came tumbling back, not only into school life, but back with a thud into the Middle Remove and all its old miseries and animosities.

“I might have known what to expect!” he cried with futile passion. “It’s just your style, doing the spy!”

Haigh took much less notice of this insult than he took of a false quantity in a Latin verse. He turned his attention to Mulberry, who had scrambled to his feet. Leaning through the forked tree, Haigh held out his hand for the stamped envelope, was given it without a word, and read it as he came round into the open.

“This looks like your writing, Rutter?”

“It is mine.” Jan was still more angry than abashed.

“May I ask what it refers to?”

“You may ask what you please, Mr Haigh.”

“Come, Rutter! I might have put more awkward questions, I’d have thought. Still, as it won’t be for me to deal with you for being here instead of where you’re supposed to be, I won’t press inquiries into the nature of your dealings with this man.”

It was Mulberry’s cue. He dashed his battered hat to the ground with ominous relief.

“D’you want to know what he’s had off me? If he won’t tell you, I will!”

Jan’s heart sank as he met a leer of vindictive triumph. “Who’s going to believe your lies?” he cried out, in a horror that increased with every moment he had for thought.

“I’m not going to listen to him,” remarked Haigh unexpectedly. “Or to you either!” he snapped at Jan.

“Oh, ain’t you?” crowed Mulberry. “Well, you can shut your ears, and you needn’t believe anything but your own eyes. I’ll show you! I’ll show you!”

He dived into a bramble bush alongside the forked tree. His head disappeared in the dense green tangle. He almost lost his legs. Then a hand came out behind him, and flung something at their feet. It was an empty champagne bottle. Another followed, then another and another till the open space was strewn with them. Neither Haigh nor Jan said a word, but from the bush there came a gust of bawdy coarseness with every bottle, and last of all the man himself waving one around like an Indian club.

“A live ’un among the deaders!” he hooted rapturously. “Now I can drink your blessed healths before I go!”

Master and boy looked on like waxworks, without raising a hand to stop him or a finger to brush away a fly. Jan neither realised nor cared what was happening. It was the end of all things, for him or for Evan, if not for them both. Evan would hear of it — and then — and then! But would he hear? Would he necessarily hear? Jan glanced at Haigh, and saw something that he almost liked in him at last, something human after all these years — but only until Haigh noticed him looking and promptly fell upon the flies.

Mulberry meanwhile had knocked the neck off the unopened bottle with a dextrous blow from one of the empties. A fountain of foam leapt up like a plume of smoke. The expert blew it to the winds, and drank till the jagged bottle stood on end upon his upturned face. His blood ran scarlet with the overflowing wine, which had the curiously clarifying effect that liquor does on the chronic alcoholic. It made him sublimely sober for about a minute. He belched resoundingly. Then those dim red eyes fixed themselves on Jan’s set face, and burst into a flame of recognition.

“Now I remember! Now I remember! I told him I’d seen him —”

He pulled himself up short. He had nearly spoilt his own story. He looked Jan deliberately up and down, did the same to Haigh, and only then snatched up his ugly cudgel.

“You’d better be careful with that,” snapped Haigh with the face which had terrorised generations of young boys. “And the sooner you clear out altogether, let me tell you, the safer it’ll be for you!”

“No indecent haste,” replied Mulberry, leaning at ease upon his weapon. The wine even reached that treacherous tongue of his, reviving its humour and the smatterings of earlier days. “Festina whats-’er-name — meaning don’t you be in such a blooming hurry! That nice young man o’ yours and me, we’re old partic’lars, though you mightn’t think it. Don’t you run away with the idea that he’s emptied all them bottles by his little self! It wouldn’t be just. I’ve had my share. But he don’t like paying his, and that’s where the trouble is. Now we don’t keep company no more, and I’m going to tell you where that nice young man an’ me first took up with each other. Stric’ly ’tween ourselves.”

“I’ve no wish to hear,” cried Haigh. He looked exactly as Jan had seen him look before running some fellow out of his hall. “Are you going of your own accord —”

“Let him finish,” said Jan, with a grim impersonal interest. In any case it was all over with him now.

“Very kind o’ nice young man — always was nice young man!” said Mulberry. “Stric’ly ’tween shelves, it was in your market place, one blooming fair, when all good boys should ha’ been tucked up in bed an’ ’sleep. Nasty night, too! But that’s where I see ’im, havin’ barney about watch, I recollec’. That’s where we first got old partic’lars. Arcade Sambo, as we used say when I was at school. I seen better days, remember, an’ that nice young man’ll see worse, an’ serve him right for the way he’s tret his ol’ partic’lar, that took such care of him at the fair! Put that in your little pipes an’ smoke it at the school. Farewell, a long farewell! Gobleshyer ... Gobleshyer ...’

They heard his repeated blessings for some time after he was out of sight. It was not only distance that made them less and less distinct. The champagne was now his master — but it had been a good servant first.

“At any rate there was no truth in that, Rutter?” Haigh seemed almost to hope that there was none.

“It’s perfectly true, sir, that about the fair.”

“Yet you had the coolness to suggest that he was lying about the wine!”

“I don’t suggest anything now.”

Jan kicked an empty bottle out of the way. Haigh’s new tone had cut him as deep as in old odious days in form.

“Is that your money he’s left behind him?” Jan’s answer was to go down on his knees and begin carefully picking up the forgotten coins from the carpet of last year’s leaves. Haigh watched him under arched eyebrows, and once more the flies were allowed to settle on his limp collar and wet wry face. Then he moved a bottle or two with furtive foot, and kicked a coin or two into greater prominence, behind Jan’s bent back.

“When you’re quite ready, Rutter!” said Haigh at length.

26. Close of play

It is often remarked of people who go through life fretting over trifles and making scenes out of nothing at all, that in a real emergency their calmness is amazing. Yet, if one thinks about it, it is not really surprising. A crisis brings its own armour, but a man is naked to the insect bites of the passing moment, and he may have a tender skin. This was the trouble with Mr Haigh. He was a naturally irritable man, who over long years of chartered tyranny had ceased to control his temper, unless there was some special reason why he should. But fellows in his house used to say that in the worst type of row they could trust Haigh to sort the sinned against from the sinning and not to lose his head, though he might still smack theirs for whistling in his quad.

Thus Haigh already had more sympathy with the serious offender whom he had caught red-handed than with little clods who ended pentameters with adjectives or showed a depraved disregard for the caesura. But for once he did not wear his heart upon his sleeve. His very shoulders, as Jan followed them, looked laden with inexorable fate. Steely composure is as terrible as wrath. It chilled Jan’s blood, but it also gave him time to make up his mind.

In the wood and in the ride Haigh did not even turn his head to see that he was being followed, but in the lower meadow he stopped and waited sombrely for Jan.

“There’s nothing to be said, Rutter, between you and me, except on one small point that doesn’t matter to anybody else. I gathered just now that you were not particularly surprised at being caught by me — that it’s what you’d have expected of me — playing the spy! Well, I have played it during the last hour; but I’d never have dreamt of playing it if your own rashness hadn’t forced me to.”

“I suppose you saw me get into the fly?”

“I couldn’t help seeing you. I’d called for this myself, and was bringing it to you for your — splitting head!”

Haigh had produced a medicine bottle sealed up in white paper. Jan could not resent his sneer.

“I’m sorry you had the trouble, sir. There was nothing the matter with my head.”

“And you can stand there —”

Haigh did not finish his sentence, except by flinging the medicine bottle to the ground in disgust, so that it broke even in the soft grass and its contents soaked the white paper. This was the old Adam, but only for a moment. Jan could almost have done with more of him.

“I know what you must think of me, sir,” he said. “I had to meet a blackmailer at his own time and place. But that’s no excuse for me.”

“I’m glad you don’t make it one. I was going on to tell you that I followed the fly, only naturally, as I think you’ll agree. But it wasn’t my fault you didn’t hear me in the wood before you saw me. I made noise enough, but you were so taken up with your — bosom friend!”

Jan did resent that, very much. But he had made up his mind not even to start the dangerous game of self-defence.

“He exaggerated that part of it,” was all that he said, dryly.

“So I should hope. It’s not my business to ask for explanations —”

“And I’ve none to give, sir.”

“It’s only for me to report the whole matter, Rutter, as of course I must at once.”

Jan looked alarmed.

“Do you mean before the match is over? Must the Eleven and all those Old Boys —”

“Hear all about it? Not necessarily, I should say, but it won’t be in my hands. The facts are usually kept quiet in — in the worst cases. But I shan’t have anything to say to that.”

“You would if it were a fellow in your house!” Jan could not help replying. “You’d take jolly good care to have as little known as possible — if you don’t mind my saying so!”

Haigh did mind. He was a man to mind the slightest criticism, and yet he took this from Jan without a word. The fact was that, much to his annoyance and embarrassment, he was beginning to respect the youth more in his downfall than at the height of his cricketing fame. He had grudged Rutter his great and unforeseen success at school, for Rutter had been as surly a young numbskull as ever impeded the work of the Middle Remove and the only one who had ever, ever scored off Mr Haigh. Yet now he recognised the manliness of his bearing in adversity — and such adversity, at such a stage in his career! There had been nothing abject about it. Now there was neither impertinence nor bravado, but rather an unexpected sensitiveness, a redeeming spirit. Yet it was an aggravated case, if ever there was one. A more deliberate and daring piece of trickery could not be imagined. And yet he found himself making jaunty remarks to Jan about the weather, and even laughing raucously about nothing, for the driver’s benefit as they came up to where the fly was waiting in the road.

Haigh of all masters, and Jan Rutter of all the boys who had ever been through his hands! That was the feeling that preyed upon the man, the weight he tried to get off his chest when they had dismissed the fly outside the town, and had walked in together as far as Heriot’s quad.

“Well, Rutter, there never was much love lost between us, was there? And yet — I don’t mind telling you — I wish any other man in the place had the job you’ve given me!”

The quad was still deserted, but Jan had scarcely reached his study when he heard a hurried step in the passage, and a small fag from another house appeared at his open door.

“Oh, please. Rutter, I was sent to fetch you if you’re well enough to bat.”

“Who sent you?”

“Goose.”

“How many of them are out?”

“Seven when I left.”

“How many runs?”

“Hundred and sixty just gone up.”

“It hadn’t! Who’s been getting them?”

“Devereux, mainly.”

The fag reported later that Rutter lit up at this, gave the most extraordinary laugh, and suddenly asked if Devereux was out.

“And when I told him he wasn’t,” said the fag, “he simply sent me flying out of his way, and by the time I got into the street he was almost out of sight at the other end!”

Certainly they were the only two members of the school to be seen about the town at half-past four that Saturday afternoon. Half the town itself seemed glued to the palings where Jan’s fly-man had been. And on the ground every available boy, every master except Haigh, and every single master’s lady, watched the game without a word about anything else. Even the tea-tent, that great and popular feature of the festival, was deserted.

Evan was still in with over 70 runs, Jan discovered, and playing the innings of his life, the innings of the season for the school. But another wicket must have fallen soon after the small fag fled for Jan, and Chilton who had gone in was not shaping with any great confidence. Evan, however, looked as though he had enough for two, from the one glimpse Jan had of his heated but collected face, and the one stroke he saw him make, before diving into the dressing-room to clap on his pads. To think that Evan was still in, and on the high road to a century provided somebody would hold up the other end! To think he should have chosen this very afternoon!

The Fates might have treated Jan much more harshly. They might not have given him time to put his pads on properly, they might not have allowed him to get his breath. When he had done both, and even had a wash and pulled his cap well down over his wet hair, they might have kept him waiting with his heart growing sick at the memory of the afternoon. Instead of any of this, they propped up Chilton for another 15 runs, and then sent Jan in with 33 to get and Evan not out 84.

But they might have spared him the tremendous cheering that greeted his resurrection from the sick-room to which — obviously — his heroic efforts of the morning had brought him. And Evan added a little irony of his own.

“Keep your end up,” he whispered, coming out to meet the captain a few yards from the pitch, “and I can get them. Swallow’s off the spot and the rest are pifflers. Keep up your end and leave the runs to me.”

It was the tone of a captain to his last hope. But that was lost on Jan. He could only stare at the cool but heated face, all eagerness and confidence, as though nothing whatever had been happening off the ground. And his stare did draw a change of look — a swift unspoken question — a tiny cloud that vanished at Jan’s reply.

“It’s all right,” said Jan. “You won’t be bothered any more.”

“Good man! Then only keep your end up, and we’ll have the fun of a lifetime between us!”

Jan nodded as he went to the crease. Really Evan had done him good. And in something else the Fates were kind. He did not have to take the next ball, and Evan took care to make a single off the last of the over, which gave Jan a good look at both bowlers before being called upon to play a ball.

But then it was A. G. Swallow whom he had to face and, despite Evan’s comment, that great cricketer looked as full of wisdom, wiles, and genial malice as an egg is full of meat. He took his rhythmical little ballroom amble of a run, threw his left shoulder down, heaved his right arm up, and nicked finger and thumb together as though the departing ball were a pinch of snuff. I. T. Rutter — one of the many left-hand bowlers who bat right-handed — watched its trajectory with terror tempered by a bowler’s knowledge of the kind of break put on. He thought it was never going to pitch, but when it did, well to the off, he scrambled in front of his wicket and played the thing somehow with bat and pads combined. A. G. Swallow awaited the ball’s return with a smile of settled sweetness, and E. P. Devereux frowned.

The next ball flew higher, with even more spin, but broke so much from leg as to beat everything except Stratten’s hands behind the stumps. Jan had not moved his feet. He had simply stood there and been shot at, yet already he was beginning to perspire. Two balls and two such escapes were enough to upset anybody’s nerve. He knew enough about batting to know what a bad bat he was, and the knowledge often made him worse still. He had just one point in his favour: as a bowler he could put himself in the bowler’s place and consider what he himself would try next, if he were bowling.

Perhaps the finest feature of Swallow’s slow bowling was the fast one that he could send down, when he liked, without perceptible change of action; but the other good bowler rightly guessed that this fast ball was coming now, was more than ready for it, let go early and with all his might, and happened to time it to perfection. It went off his bat like a tennis ball from a tight racket, flew high and square (though really intended for an on-drive), and came down on the pavilion roof with a heavenly crash.

The school made music too; but Evan looked disturbed, and it was a good thing there was not another ball in the over. Swallow did not like being hit. It was his only foible, but to hit him half by accident was to expose one’s wicket to all the knavish tricks that could possibly be concentrated in the next delivery.

Now, however, Evan had his turn again, and picked five more runs off three very moderate balls from Whitfield. The fourth did not defeat Jan, and Evan had Swallow’s next over. He played it like a professional, but ran rather a sharp single off the last ball, and proceeded to nurse the bowling as though his partner had not made 25 not out in his first innings and already hit a six in his second.

Jan did not resent this in the least. The height of his own ambition was simply to stay there until the runs were made. The next essential was for Evan to reach his century, which was necessary anyway if the runs were to be made, and at this rate he would not be long about it. To Jan his performance was a revelation of character and capacity. Surely it was not Evan Devereux batting at all, but a higher order of cricketer in Evan’s image, an altogether stronger soul in his skin. Even that skin looked different, so fiery red and yet so free from the sweat that welled from Jan’s pores.

So thought Jan at the other end. But all these thoughts were subconscious, crowded out by all manner of impressions and reminiscences. For out there on the pitch he had found himself in a rarefied atmosphere, seeing and doing things for the last time, and more vividly and with greater gusto than he had ever seen or done them before.

Though he had played upon it literally hundreds of times, never until to-day had he seen what a beautiful ground the Upper really was. On three sides a smiling land fell away from the very boundary, as though a hill-top had been sliced off to make the field. On those three sides you could see for miles, and they were miles of grazing country chequered with hedges, and of blue distance blotted with trees. But even as a cricket-field Jan felt that he had never before appreciated his dear Upper as he ought. It lay so high that at one end the batsman stood in position against the sky from the pads upwards, and the heavens were the screen behind the bowler’s arm.

This fresh view of a familiar scene was due more to exaltation than to the perfect weather, let alone to the sentimentality of a farewell appearance. Jan was much too excited to think of anything but the ball while the ball was in play. But between the overs the spectres of the early afternoon were at his elbow, and in one such pause he saw Haigh, not as a spectre but in the flesh, watching from the boundary.

It was Haigh freshly groomed, in a clean collar and a different suit, the sparse hair brushed flat on his pink temples, his mouth inexorably shut on the tidings it was soon to utter. Decent of Haigh to wait until the match was lost or won. But then Haigh resembled the Upper, for Jan was already liking everything around him better than he had ever done before. In front of the pavilion, in tall hat, frock-coat and white cravat, sat splendid little old Jerry himself, that flogging judge who was soon to assume the black cap at last, but still ignorant of the capital offence committed, still beaming with delight and pride in a glorious finish. Elsewhere a pair of familiar faces made themselves seen and heard — gaunt old Heriot, who in his innocence had bawled a bravo for the six, and beside him the gay young dog into which Oxford had already turned the austere Crabtree.

Jan wondered what those tense faces on the boundary were saying at this moment. He soon saw. Charles Cave was coming on to bowl instead of Swallow, and it was Jan who had to face him. But he was almost at home by this time, and all four balls found the middle of his bat. Then A. G. Swallow made an audacious move.

Of course he must know what he was doing, for he had led a first-class county in his day, and had never been the captain to take himself off without reason. No doubt he understood the value of a double change. But was it really wise to put on Swiller Wilman at the other end with lobs, when only 15 runs were wanted to win the match? Pavilion critics had their doubts about it. Old judges on the rugs had none at all, but gave Devereux a couple of overs for the winning hit. Only Evan himself betrayed any apprehension as he beckoned to Jan before the lobs began.

“Any idea how many I’ve got?” he asked below his breath. The second hundred had just gone up to loud applause.

“I can tell you to a run if you want to know.”

“I’m asking you.”

“You’ve made 94.”

“Rot!”

“You have. You’d made 84 when I came in. I’ve counted your runs since then.”

“I’d no idea it was nearly so many!”

“And I didn’t mean to tell you.”

That had been wise of Jan, but it was not so tactful to remind the batsman of every batsman’s anxiety on nearing the century. Evan’s face turned redder than before.

“Well, don’t you get out off Wilman,” he said.

“I’ll try not to. Let’s both follow the rule, eh?”

“What rule?”

“Dudley Relton’s for lobs: a single off every ball, never more and never less, and nothing whatever on the half-volley.”

“Oh, be blowed!” said Evan. “We’ve been going far too slow these last few overs as it is.”

Accordingly he hit the first lob just over mid-on’s head for three, and Jan got his single off the next, but off both of the next two balls Evan was very nearly out for 97 and the match lost by 10 runs.

On the second occasion even George Grimwood conceded that off a lob a fraction faster Mr Devereux would indeed have been stumped; as it was he had only just got back in time. This explanation was not endorsed by Mr Stratten, whose vain appeal had been echoed by half the field. That nice fellow was not looking nearly so nice as he crossed to the other end.

The next incident was a full-pitch to leg from Charles Cave and a four to Jan Rutter. That made 6 to tie and 7 to win, but Jan could hardly score off more than one more ball if Evan was to get his century. Jan thought of that as he played hard forward to the next ball but one, and felt it leap and heard it hiss through the covers, for even his old bat was driving as it had never done before. But a deep-field sprinter just saved the boundary, and Jan would not risk the more than possible third run.

The score now stood at 210. Five runs were wanted to win the match. And Evan Devereux, within three of every cricketer’s ambition, again faced the merry underarm bowler against whom he had shaped so precariously the over before last.

George Grimwood could be seen shifting from foot to foot as he jingled the pence in his palm. Another of those close shaves was not wanted this over, with the whole match hanging on it, and Mr Stratten still looking like that ...

A bit better, that was! A nice two for Mr Devereux to the unprotected off — no! — blessed if they aren’t running again! They must be daft — one of them’ll be out, one of ’em must be! No — a bad return — but Mr Cave has it now. He’s got a return like a young cannon, and here it comes!

No umpire will be able to give this in — there’s Mr Rutter a good two yards down the pitch, legging it for dear life — and here comes the ball like a bullet — he’s out if it doesn’t miss the wicket. But it does miss it, by a coat of varnish, and ricochets to the boundary for another four that win the match for the school and the ultimate honour of three figures for Evan Devereux.

Over the ground swarm the whole school, but Evan and Jan have been too quick for them and break through the first arrivals. And, after all, it is not Lord’s or the Oval. Nobody cares much who wins this match, it’s the magnificent finish that matters and will matter while the school exists.

The now dense mass before the pavilion parts in two, and the smiling Old Boys march through the lane, which does not close up again until Rutter has come out and given Devereux his colours in the time-honoured way, by taking the blue sash from his own waist and tying it round that of his friend.

Did somebody say that Devereux was blubbing from excitement? No, he was not. But nobody was watching Jan.

27. The extreme penalty

Foreheads were not wiped before the question arose, “What shall we do till lock-up?” For the Eleven the answer was simple: to talk it all over in that sanctum of swelldom, the back room at Maltby’s. Their latest member had a tremendous telegram to send to his people, but after that, to the team’s surprise, he did not join them. Neither did the Captain of Cricket, though for once in his captaincy he would have been really welcome.

Evan had retired to his house, not a bit as though the school belonged to him and with little of the habitual strut (now that he had something to strut about) in his unsteady gait. Jan had installed himself in Heriot’s, quite unnecessarily prepared to dodge Evan, or to protect himself with a third person if run to ground. The third person was naturally Chips, who had gone mad on the Upper and was now working off the fit in a parody of The Battle of Blenheim in place of an ordinary prose report of the most famous of all victories.

After an hour or so, though there was no sign of Evan and little likelihood of his appearing now, Jan was still dodging like an uneasy spirit in and out of Chips’s study. Once he remarked that there was an awful row in the lower passage, implying that Chips ought to go down and quell it. But Chips had never been a Crabtree in the house, and at present he was too deep in his rhyming dictionary to hear either the row or Jan.

Lock-up at last. The little block of ivy-mantled studies became a factory of proses and verses, all Latin except the Greek iambics of those high up in the school, and all to be signed by Heriot after prayers that night or first thing in the morning, to show that the Sabbath had not been profaned by secular work.

Nine o’clock. Prayers approached, and yet Jan still sat unmolested in his disorderly study, and yet the heavens had not fallen with the wrath of Heriot or of anybody else. Could it be that for the second time Jan was to be let off by the soft-heartedness of a master who knew enough to hang him? Hardly! Hardly from Haigh, of all men! Yet he had been awfully decent about it all. It was a revelation to Jan that after all there was so much common decency in his oldest enemy ...

Now he would soon know. There was the old harsh bell, rung by Morgan outside the hall, across the quad.

Prayers.

Jan had scarcely expected to go in to prayers again, and as he went he remembered his first impressions of them at the beginning of his first term. He remembered the small boy standing sentinel in the flagged passage leading to the green-baize door, and all the fellows armed with hymn-books and chatting merrily in their places. That small boy was a big fellow in the Sixth Form now, and the chat was more animated but less merry than it had seemed to Jan then. Something was in the air. Could it have leaked out before the sword descended? No. It must be something else. Everybody was eager to tell him about it, as he repeated ancient history by coming in almost last.

“Have you heard about Devereux?”

“Have you heard, Rutter?”

“Haven’t you heard?”

His heart missed a beat.

“No. What?”

“He’s down with measles!”

“That all!” exclaimed Jan, as his heart recovered.

If his own downfall had been in vain!

“It’s bad enough,” said the big fellow who had stood sentinel four years ago. “They say he must have had it on him when he was in, and the whole thing may make him jolly ill.”

“Who says so?”

“Morgan. He’s just heard it.”

Poverty of detail was eked out by fertile speculation. Jan was hardly listening. How would this new catastrophe affect himself? Evan was as strong as a horse, and had his magnificent century to look back upon from his pillow. That was enough to see anybody through anything. And now there was no question of his coming forward and owning up, for who was going to carry a school scandal into the Sanatorium, even if the school ever heard the story?

And yet somehow Jan felt as though a loophole had been stopped at the back of his brain, and on investigating he was ashamed to discover what the loophole had been. Evan would have found out, and would never have let him bear the brunt. In the end Evan’s honesty would have saved them both, because nothing paid like honesty with dear old Thrale. That was what Jan saw, now that seeing it could only make him feel a beast. It was almost a relief to realise that Evan would still be ruined if the truth leaked out through other lips. Which sealed his own closer than before.

The Heriots were very late in coming in. Why was that? But at last the sentinel hissed “Hush!” and sister and brother entered in the usual silence.

Miss Heriot took her place at the piano under the shelf bearing the now solitary cup of which Jan might almost be described as the solitary winner; at any rate the present house eleven consisted, like the historic Harrow eleven, of Rutter ‘and ten others.’ The ten others — the thirty others — then present could not have guessed a tenth or a thirtieth part of what was in their bowler’s mind that night.

The Heriots always chose a good hymn. Tonight it was No 477 Ancient and Modern, rather a favourite of Jan’s. He found himself braying out the tune from the Sixth Form table, while Chips lorded it like every captain of the house with his back to the empty grate, fondly imagining that he was singing bass. Neither of them did much credit to the most musical school in England, and now only one of them could go about saying that he had ever been there. Then the words that Jan was singing sank in.

The day thou gavest, Lord, is ended,

The darkness falls at thy behest ...

The darkness was falling, and he fell silent. Unless ... But there was no telling from Heriot’s voice as he read the prayers. It was the same unaffected voice which had appealed to Jan on his very first night in hall. The prayers were the same, a selection used only in that house. Jan now knew them all off by heart, but listened with no less care in order to remember them at the ends of the earth.

“O Lord, who knowest our peculiar temptations here, help us to struggle against them. Save us from being ashamed of our duty. Save us from the base and degrading fear of one another ...”

Well, he had stood up sufficiently, he hoped, to the other old members of the Eleven, and without too much fear. As for his duty, he had tried to meet the obligation of friendship, hadn’t he? Even if it had brought him to grief ...

“Grant that we may always remember that our bodies are the temple of the living God, and that we may not pollute them by evil thoughts or evil words or evil deeds ...”

Well, foul language had never been his habit, though he had said words, sometimes, which some might have seen as evil. As for evil thoughts and evil deeds, he knew what they meant in the context, and to them he had to plead ... well ...

“Give us grace never to approve in others what our consciences tell us is wrong, but to reprove it either by word or by silence. Let us never ourselves act the part of tempter to others, never place a stumbling-block in our brother’s way, or offend any of our companions ...”

Well, he had never played the tempter or placed stumbling-blocks, whatever else he had done. As for reproof, he had never been so particular as old Chips who in his early days had gone to the foolhardy length of reproof by word, and who even now was rising from his knees as though he had been really praying. But Jan knew he had not been, any more than had Jan himself, who had only been thinking his own thoughts, though kneeling there without doubt for the last time.

And yet another doubt ran through him as Heriot took his usual stand in front of the grate, and some of the fellows made a dash for milk and dog-rocks at the bottom of the long table, but more clustered round the fireplace to hear Heriot and Jan discuss the match. They actually did discuss it for a minute or two, but Heriot, despite his intentions, was dry as tinder. When he suddenly announced that he would sign all verses in the morning, but would like to speak to Rutter for a minute, Jan followed him through into the private side with a stabbing conviction that it all was over.

“I’ve heard Mr Haigh’s story,” said Heriot very coldly in his study. “Do you wish me to hear yours?”

“No, sir.”

Jan did not wince at Heriot’s tone, but Heriot did at his. The one was to be expected, the other almost brazen in its unblushing readiness.

“You have nothing whatever to say for yourself, after all these years, after —”

Heriot pulled himself up with a jerk of the grizzled head and a fierce flash of the glasses.

“But from all I hear I’m not surprised,” he added with bitter significance. “I find I’ve been mistaken in you all along.”

Yet Jan did not see the significance at the time, and the bitterness only allowed him to seem indifferent.

“There’s nothing to say, sir. I was shamming right enough, and I suppose Mr Haigh has told you why.”

“He has indeed! The matter has also been reported to the Headmaster, and he wishes to see you at once. I need hardly warn you what to expect.”

“No, sir. I expect to go.”

“Evidently you won’t be sorry, so I shan’t waste any sympathy on you. But I must say I think you might have thought of the house!”

Jan had not thought of it that way, and sympathised. He did not spot an unworthy but most human element in Heriot’s outlook. The house would not be ruined for life. But Jan, in his determination to put a stiff lip on every phase of his downfall and never to betray himself by breaking down, had over-acted like most unskilled players. He had already created an impression of coarse bravado on a mind ready to stretch any possible point in his favour.

But there was no time to think about Bob Heriot now, when truly terrible retribution awaited him from the redoubtable old Jerry. About a hundred yards of the soft summer night, and he would stand in that awful presence for the last time. It was all very well for Jan still to call him ‘old Jerry’ in his heart, and to ask himself what there was to fear so acutely from a man of nearly seventy who could not eat him. His heart quaked none the less, and he dared to dawdle on the way, recalling his past relations with the great little old man. There was the time he was nearly flogged after the Abinger affair. Well, Jerry might have been far more severe than he had been. There was the aftermath of the haunted house. There was that early occasion when Jan was told that another time he would not sit down so comfortably, and Chips’s story about his friend Olympus. Such grim humour appealed to Jan. But it was a humour that became terrible whenever Jerry held the whole school responsible for some individual crime. He would show that they were all dogs and curs together, lash them with his tongue, and dismiss them with ‘Dogs, to your kennels!’ And go they would, feeling beaten mongrels every one, never laughing at the odd old man, never even reviling him, often loving but always fearing him.

Jan now feared him the more, because he had recently been learning to love Mr Thrale. Though still only in the Lower Sixth, as Captain of Cricket he had come in for various ex-officio honours in the shape of breakfasts and audiences formal and informal. On all these occasions Jan had been embarrassed and yet braced, puzzled by parables but enlightened in flashes, stimulated in soul but awed from skin to core. And now the awe was undiluted, crude, and overwhelming. He felt that every word from that trenchant tongue would leave a scar for life, and the scorn in those old eyes haunt him to his grave.

Subconsciously he was thinking of the judge and executioner in his gown of office, on his carved judgement seat, as the day’s crop of petty offenders faced him after twelve. In his library Jan had seldom before set foot, and never with the seeing eye that he brought tonight. The smallness and simplicity of it struck him through all his tremors. It was not much larger than the large studies at Heriot’s. Only a gangway of floor surrounded a great desk in a litter after Jan’s own heart. Garden smells came through an open window, and with them a maze of midges to dance round the one lamp set amid the litter. And in the light of that lamp, a pale face framed in silvery hair, wide eyes filled with heart-broken disgust, and a mouth that might have been closed for ever.

At last it came to life, and Jan heard a brief and dispassionate recital of all that Haigh had heard and seen in the fatal hour when pretended illness kept Jan from the match. Again he was asked if he had anything to challenge or to add, and again Jan had no answer and could only shake a bowed head humbly. Jerry was far less fierce than he had expected, but a hundred times more terrible in his pale grief and scorn. It was impossible even to remember that Jan was not the vile thing he was made out to be.

“If there is one form of treachery worse than another,” said Mr Thrale, “it is treachery in high places. The office that you have occupied, Rutter, is rightly or wrongly a high one in this school; but you have dragged it in the dust, and our honour stands above our cricket. On the eve of our school matches, when we had a right to look to you to keep our flag flying, you have betrayed your trust and forfeited your post and your existence here. Even if it were the end of cricket in this school, I would not keep you another day.”

Jan looked up suddenly.

“Am I to go on a Sunday, sir?”

The thought of returning to the Norfolk rectory in dire disgrace had suddenly taken frightening shape. On a Sunday it would be too awful, with the somnolent household in a state of either complacent indolence or sanctified fuss, assimilating sirloin or starting for church, depending on when he arrived.

But Mr Thrale was considerate. “You will remain till Monday. Meanwhile you are to consider yourself a prisoner on parole, and mix no more in the society for which you have shown yourself unfit. So far as this school goes you are condemned to death for lying, betrayal and mock-manly meanness. Murder will out, Rutter, but you are not condemned for any undiscovered crime of the past. Yet if it is true that you ever got out of your house at night —”

Jan could not meet the awful look as Mr Thrale made a dramatic pause. But he filled it by mumbling that it was quite true, he had got out once, over two years ago.

“Once is enough to deprive you of the previous good character that might otherwise have been taken into consideration. I do not say it could have saved you. But nothing can save the traitor guilty of repeated acts of treason. A certain consideration you will receive at Mr Heriot’s hands, by his special request, until you go on Monday morning. And that, Rutter, is all I have to say to you as Headmaster of this school.”

It is in this way that the convicted murderer is handed over to the High Sheriff for execution. But just as other judges soften the dreadful language of the law with more human words of their own, so did Mr Thrale talk to Jan as man to man. He asked him what he was going to do, and begged him not to see his whole life as necessarily ruined. The greater the fall, the greater the merit of rising again — almost the greater the sport! Let him take life as a game, bowl out the devil that was in him, and pull his own soul out of hell. He enlarged on the lust of drink, bluntly but with gentle understanding, as a snare set for just and unjust alike, a curse most accursed in its destruction of the moral fibre. Jan, listening humbly, felt as if his own body and soul had been already undermined. He thought he saw tears in the old man’s eyes. He knew he had them in his own. The harangue, begun between man and man, ended almost as father to son, with a handshake and “God guide you!” There was even the offer of a letter which, while not glozing over the worst, would say what could still be said and might be useful if Jan were man enough to show it in Australia.

But meanwhile he had been expelled from school, expelled in his last term, while Captain of Cricket, on the crest of his one triumph as captain. And on his way back to his house Jan stopped in the starlit street, and astonished himself.

As he suddenly remembered the actual facts of the case, he laughed aloud.

28. Lucifer

Heriot himself showed Jan to his room, the spare bedroom on the private side, where he was to remain until he went. All his belongings had been brought from his dormitory, and some few already from his study. The bed was made and turned down, and there was an adjoining dressing-room at his disposal, with the gas lit and hot water brought up by some unenlightened maid. This led Heriot to explain, very gruffly, the special consideration to which Mr Thrale had referred.

“The whole thing’s a secret from the house so far, and of course the servants know nothing about it. They probably think you’re suspected of measles, not strongly enough for the Sanatorium but too strongly for the sick-room on the boys’ side. I shall allow that impression to prevail until — as long as you remain.”

“Thank you, sir.”

“I remember better days, Rutter. We’d seen a good many together before you came to anything like this.” His glasses flashed. “Yet all the time —”

He stopped himself as before, turned on his heel and shut a window which he had just opened. This time Jan guessed what it was that Heriot could not trust himself to mention. He was glad to be bidden an abrupt good-night, and left alone at last.

Alone in the condemned cell, or rather a luxurious suite of cells. The luxury was an irony not lost on Jan. He was as alive to every detail of his surroundings as he had been towards the end of the match. And the grim humour of the situation, which had only come home to him since his interview with the Headmaster, was still a relief after the solemnity of that ordeal. He must never again forget that he was guiltless. That made all the difference in the world. Could he have thought of condemned cells if he deserved to be in one, or of the portmanteau he found in the dressing-room, lying ready to be packed, as the open coffin of his school life?

And yet it was, it was!

The night was long and wakeful, disturbed by ominous memories. They began when he emptied his pockets before undressing and missed the small gold watch which had been his mother’s when she ran away from home. This was the first night in all his schooldays that he had been without it. Again he remembered wondering if the boys would laugh at him for having a lady’s watch; but they were marvellously decent about some things, and not one of them had ever commented. The little gold watch had timed him through all these years, and now, the first occasion he had left it behind, he had come to grief. It was only in the studies, but it would never bring his luck back now.

Then there was that pocketful of small silver and stray gold. Two pounds eighteen and sixpence, he ought to make it; and he did. The amount was not the only thing about the money that he recalled. He took an envelope from the stationery case, swept all the coins in and stuck it up with care. He even wrote the amount outside before dropping the jingling packet into a drawer in the dressing-table. He then got into bed in the superfine sheets dedicated to guests — his own sheets would not have stretched across this great mattress — and these reminded every inch of him where he was, every hour of the night.

He heard them all struck by the old blue church clock. It was the first time he had heard it like this since he had moved out of the little front dormitory, his first year in the Eleven. It was strange to be sleeping over the street again, listening to all its old noises ... listening ... listening again ... listening always to the old harsh bell.

That was the worst noise of all. He must have been asleep, in spite of everything, and only really woke up standing on the soft, spacious, unfamiliar floor. The spare bedroom was full of summer sunshine. The fine weather had come to stay. They would get a fast wicket over at Repton next weekend, and Goose would have to win the toss. Goose!

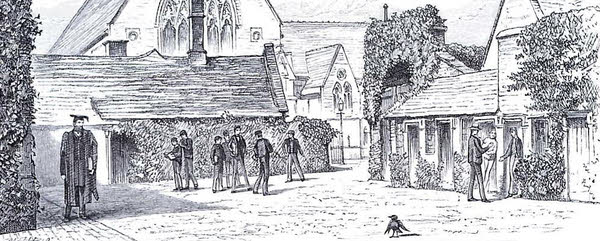

Meanwhile it was only Sunday. Jan knew the habits of his house on Sunday morning, and now was his chance of the bath. Bathrooms were not plentiful in those days. There was only one between both sides of the house, not counting the shower off the lavatory which was now out of bounds. The bathroom was in bounds, just, and Jan got to it first, bolted both doors and looked out into the quad while the bath was filling.

Those cursed memories! Here was another, of his very first sight of the quad, his very first morning in the school ... Well, he had lived to be cock of that walk, and on those fives courts he was leaving no one better. But how pleasant it all looked in the cool morning sun! There is a peculiar quality about Sunday sunshine, a restfulness at once real and imaginary. It was very real to Jan as he took leave of the quiet study windows, the empty garden seats shaded by the laburnum with its shrivelled blossoms, the little acacia, and the plane-tree which had been blown down once and ever since held in leash by a chain. Closer at hand, hardly out of reach, the dormitory windows stood wide open, but nobody got up in dormitory till the last five minutes on a Sunday morning. So Jan gloated unobserved on the scene of so much that had happened to the house and to him — of Sprawson’s open pranks and Shockley’s wary brutalities. It was down there that Mulberry first showed his fatal nose and Jan was christened Tiger, and it was there they lit up a slide with tollies at the end of his first winter term. Now it was the end of all terms, and in a night the old quad had changed into a place of the past.

It was better in the cells at the front of the house. It might have been quite bearable there, but for the bells. But on a Sunday the cracked bell rung by Morgan in the quad was nothing to the bells you heard on the other side of the house, if you came to listen to them as Jan did. There was evidently an early celebration in the parish church as well as in chapel, but that was the only time the rival bells rang a duet of sedate discords. All the rest of the day they followed each other in proper sequence.

The chapel bells led off with their incorrigibly merry measure. It was worse to hear the accompanying tramp of boys in twos and threes, in Sunday tails or Eton jackets, looking heartlessly content with life, taking off praepostorial hats or touching common school caps to gowned and hooded masters; for Jan was obliged to peep through the blind, not deliberately to make things worse, but for the sake of a moment’s distraction. That was all he got. There were heaps of fellows now to whom he could not put a name, for mere mortal boys do not excite the curiosity of gods, but once or twice poor Lucifer espied some still unfallen angel in the ribbon of shade across the street. One was Ibbotson of the Eleven — a god with clay feet if ever there was one — but there he went, looking the god all over, to the happy jingle of those callous bells. Ibbotson would come down as an Old Boy and never think twice of what he had really been. Why should he? Jan, at all events, was not his judge. Yet he would be one of Jan’s.

The church bells came as a relief, richer in tone, poorer in association, with townspeople on the pavement and not a sound in the house. Jan fell to and packed. All his clothes had been brought in now and his study possessions would be sent after him. So Mr Heriot had looked in to say, and at the same time to extract a promise that Jan would not again set foot on the boys’ side of the house. He wondered if the bath had been judged a step too far in that direction, and what it was feared that he might do when all their backs were turned. But he gave his word without complaining.

Never had condemned man less cause for complaint. Excellent meals were brought to the spare room. There was the usual sound fare for dinner, including the inevitable cold apple pie with cloves in it, and a long glass of beer to which (in those unregenerate days) Jan’s exalted place in the house entitled him. Morgan, at any rate, could not know what he was there for. Jan was wondering whether it was enough to make him sleepy after his wretched night, and so kill an hour of this yet more wretched day, when the door burst open without preliminary knock, and Chips stood wheezing on the other side of the bed.

His shoulders heaved and his face was intense and agonised. It was plain at a glance that old Chips knew something.

“Oh, Jan!” he cried. “What did you do it for?”

“That’s my business. Who sent you here?”

“I got leave from Heriot.”

“Very good of you, I’m sure!”

“That wasn’t why I came,” said Chips, stung by this reception. He shut the door behind him and walked round the bed with the extremely determined air of one in whom determination was not a habit.

“Well, why did you come?” inquired Jan, though he was beginning to guess.

“You did a thing I couldn’t have believed you’d do!”

“Many things, it seems.”

“I’m only thinking of one. The others don’t concern me. You went into my study and — and broke into the house money-box!”

“I left you something worth five times as much, and I owned what I’d done in black and white.”

“I know that. Here’s your watch and your I.O.U. I found them after chapel this morning.”

Jan took his treasure eagerly, laid it on the dressing-table, and produced his packet of coins from one of the drawers.

“And here’s your money. You’d better count it, but you won’t find a sixpence missing.”

Chips stared at him.

“But what on earth did you borrow it for?”

“That’s my business,” said Jan in the same tone as before, though Chips had changed his.

“I don’t know how you knew I had all this money. It isn’t usual late in the term like this, when all the subs have been banked long ago.”

Jan said nothing.

“This is my business, you know,” persisted Chips.

“Oh, is it? Then I don’t mind telling you I heard you filling your precious coffers yesterday after dinner.”

It was Chips’s own term for the money-box in which as captain of the house he placed the various house subscriptions as he received them. He looked distressed.

“I was afraid you must have heard me.”

“Then why did you ask?”

“I hoped you hadn’t.”

“What difference does it make?”

“You heard me with the money, and yet you couldn’t come and ask me to lend it to you.”

“I’d like to have seen you lend it!”

“This money was for something special, Jan.”

“I thought it was.”

“Half the house had just been giving me back their allowances, but some had got more from home, on purpose.”

“Yet you pretend you’d have let me touch it!”

Chips took this taunt without heat, yet with a treacherous lip.

“I would, Jan, every penny of it.”

“Why should you?”

“Because it was yours already! It was something we were all going to give you because of — because of — those cups we got through you — and — and — everything else you’ve done for the house, Jan!”

An emotional dog, this Chips. He still had the sense to see that emotion was out of place, and the self-control not to show it too much. But he could not help pushing the envelope back towards Jan, as much as to say that it was still his, that he must really take it with the good wishes he now needed more than ever. Not a word of the kind from his lips, yet every syllable in his eyes and movements. Jan, all the wind taken out of his sails, could only shake his head, wheel round, and stand looking down into the street.

29. Chips and Jan

Anybody entering the room just then would have smelt bad blood between the fellow looking out of the window and the fellow sitting on the edge of the bed. Jan’s whole attitude was one of injury, and Chips looked guilty of a grave offence against the laws of friendship. Even when Jan turned round it was with the glare which is the first skin over an Englishman’s wound. Only a hoarseness betrayed that the wound was self-inflicted and that the balm the visitor had brought was actually salt.

“I suppose you know what’s happened, Chips?”

“I don’t know much.”

“Not that I’m — going?”

“That’s about all.”

“Isn’t it enough, Chips?”

“No. I want to know why.”

“If Heriot told you so much —”

“He didn’t till I pressed him.”

“Why should you have pressed him, Chips? What had you heard?”

“Only something they were saying in the Sixth Form room. There’s nothing really got about yet.”

“You might tell me what they’re saying! I — I don’t want to be made out worse than I am.”

That was not quite the case. He wanted to know whether there was any movement, or even any strong feeling, in his favour; but it was a sudden want, and he could not bring himself to clothe it in words. It was his embryonic hope of a reprieve, a passing but irresistible whim with no reason behind it.

“They say there was nothing the matter with you yesterday afternoon.”

“No more there was. I was shamming.”

Chips felt something of Heriot’s revulsion.

“They say you went off — to — meet somebody.”

“How did they get hold of that, I should like to know?”

Of course the masters had been talking. Why shouldn’t they? But then why had Heriot pretended that nobody was to know just yet? Why had Haigh talked about the worst cases being kept quiet? Jan’s rising resentment was calmed when Chips said he believed it had come through a fly-man, at which Jan admitted that it was perfectly true.

“They say you drove out to Bardney Wood.”

“So I did.”

“It was madness!”

Jan shrugged his powerful shoulders.

“I took my risks, and I was bowled out, that’s all.”

Chips looked at him. The cynically glib admissions had been grating on him. Now they were reviving the incredulity with which he had first heard of Jan’s suicidal escapade. This shameless front was not a bit like Jan, whatever he had done, and Chips, who knew him best, was the first to perceive it.

“I wish I knew why you’d done it!” he exclaimed craftily.

“What do they say about that?”

Chips was embarrassed, because the answer reflected his own first wild suspicions.

“Well, there was some talk about — well, about a bit of a — well, romance.”

Jan’s grin made him look quite himself.

“Nicely put, Chips! But you can contradict that on the best authority.”

Chips did not allow his relief to show.

“Now it’s got about that it’s a drinking row.”

“That’s more like it.”

“It’s what most fellows believe,” said Chips, with questionable tact.

“Oh, is it? Think I look the part, do they?”

“Not look, Jan —”

“What then?”

Chips did not like going on, but had to now.

“Well, some fellows seem to think that — except yesterday, of course — your bowling —”

“Has suffered from it, eh? Go on, Chips! I like this. I like it awfully!”

And this time Jan laughed outright, but did not look himself.

“It’s not what I say, Jan! I wouldn’t hear of it.”

“Very kind of you, I’m sure. But I shouldn’t wonder if you thought it all the same.”

“I don’t, I tell you!”

“I wouldn’t blame you if you did. How things fit in! Any other circumstantial evidence against me?”

Chips hesitated again.

“Out with it, man. I may as well know.”

“Well, some say — but only some — that’s why you’ve been going about so much by yourself.”

“To go off on the spree alone?”

Chips nodded. “You see, you often refused to go out even with me,” he said reproachfully, not as though he believed the worst himself, but as an excuse for those who did.

Jan could only stare. His unsociability had been due to his unpopularity with his Eleven, his estrangement from Evan, and his delicacy about falling back on Chips. And even Chips could not see that for himself, but saw if anything with the other idiots! This was too much for Jan. It made him look more embittered than was wise if he was still to be taken as the only villain of the piece. But for the moment he was forgetting to act.

“Solitary drinking!” he exclaimed. “Bad case, isn’t it?”

“It isn’t a case at all.” Chips was looking him full in the face. “I don’t believe a word of the whole thing! Even if it’s true that you went out to Bardney to meet Mulberry —”

“Who says that?”

“Oh, it’s one of the things that’s got about. But I can jolly well see that if you did go to meet him it wasn’t on your own account!”

Confound old Chips! He could fairly see into a fellow’s skull, and make a fellow look as big a fool as he felt!

“Of course you know more about it than I do!” sneered Jan desperately. “But do you suppose I’d do a thing like that for anybody but myself?”

“I believe you’d do a jolly sight more — for Evan Devereux!”

Jan made no reply beyond an unconvincing little laugh. In his surprise at so shrewd a thrust, he was incapable of plain denial. And it showed.

“The whole thing was for Devereux!” exploded Chips with sudden conviction. “What about him and Sandham out at Bardney the other Sunday, when old Mulberry beckoned to us by mistake? Obviously he mistook us for them. I thought so at the time, but you wouldn’t have it, just because it was Devereux! What about his coming to you yesterday morning, in such a stew about something? Oh, I didn’t listen, but anybody could spot that something was up. What a fool I was not to see the whole thing from the first! Why, of course you’d never have touched that money for yourself, let alone left behind the thing I know you value more than anything else you’ve got!”

Still Jan said nothing, even when challenged outright to deny it if he could. He only stood still and looked mysterious, while he racked his brain for something to explain his look, to explain everything else that Chips had interpreted so accurately. He felt in a great rage with Chips, and yet somehow in nothing like such a rage as he had been in before. It had taken old Chips to see that he was not such a blackguard as he had made himself out. That was something to remember in the silly fool’s favour. He was the only one, when all was said and done, to believe the best of a fellow in spite of everything, even in spite of the fellow himself.

Condemned men cannot afford to send their only friends to blazes. But Chips soon got himself sent there of his own accord.

“Why should you do all this for Evan Devereux?” he demanded.

“All what, Chips? I never said I’d done anything.”

“Oh, all right, you haven’t! But what’s he ever done for you?”

“Plenty.”

“Name something — anything — he’s ever done except when you were in a position to do more for him!”

And then Jan did tell him where to go. But Chips only laughed in his face, with the spendthrift courage of a fellow who did not normally show enough of it, though he had it all the same when his blood was up. Now he was in as great a passion as Jan.

“You start cursing me because you haven’t any answer. Curse away, come to blows if you like. You shan’t get rid of me till I’ve said what I’ve got to say, not if I have to hang on to this bed and bring the place down round our ears!”

“Don’t be a fool, Chips,” said Jan, seeing that he needed self-control for two. “You know you’ve always had a down on Evan.”

“Well, perhaps I have. Doesn’t he deserve it? What did he ever do for you your first term — though he’d known you at home?”

“That was no reason why he should do anything. What could he do? We were in different houses and different forms. Besides, I was higher up in the school, as it happened, as well as a bit older.”

“That’s nothing. Still, I rather agree with you, though he was here first, remember. But what about your second term or my third? He overtook us each in turn, but did he ever go out of his way to say a civil word to either of us, though he’d known us both before?”

“Yes, he did.”

“Yes, he did! When you’d made a bit of a name for yourself over the Mile he was out for a walk with you in a minute. That’s the fellow all over, and has been all the time. I remember how it was when you got into the Eleven, if you don’t!”

But Jan did remember, and it made him think. Like most boys who are good at games, he had acquired great fairness of mind. He thought Chips was unfair to Evan. And yet he wanted to be fair to Chips, who did not know of his debt to Evan, who did not know the size of it, who did not know how Evan had been his paragon and more. All Chips knew was that the paragon was flawed. That made him jealous, though Jan was not the one to tell him so, and it made him touchy. Jan soothed the touchiness with a tact made sensitive by his own troubles.

“The fact is, Chips, you’re such a good old chap yourself that you want everybody else to be the same as you. You wouldn’t hurt a fellow’s feelings, so you can’t forgive the chaps who do it without thinking. Not one in a hundred makes as much of things as you do, or takes things so to heart. But that’s because you’re what you are, Chips. You oughtn’t to be down on everybody who doesn’t happen to be built as straight and true.”

“Don’t be too sure that I’m either!” exclaimed Chips, flinching unaccountably.

“You’re about the straightest chap in the whole school, Chips. Everybody knows that.”

“Then I’ve a good mind to set everybody right!” cried Chips wildly, worked up to more than he had dreamed of saying. “I can’t see you bunked for nothing, when others including me have done all sorts of things to deserve it. Yes, Jan, including me! You think I’ve been so straight! So I was in the beginning. So I am now, if you like. But I’ve not been all the time. No, don’t stop me, I won’t be stopped. But that’s about all I’ve got to say. I’ve always wanted you to know. You’re the only fellow in the place I care much for, who cares much for me, though not so much —”

“Yes I do, Chips, yes I do! I never thought so much of you as I do this minute. But whatever you did ... don’t you make yourself out worse than you ever were, even to me!”

“I don’t want to ... It didn’t go on long, and it’s all over long since ... But I shall get the praepostor’s medal when I leave — unless I’m man enough to refuse it — and you’ve been bunked for standing by a fellow who never would have stood by you!”

“That’s where you’re wrong, Chips,” said Jan gently.

“No, I’m not. It’s the other way about.”

“You don’t know how Evan’s stood by me all these years.”

Chips fell strangely silent — very strangely for him, especially just then. It was a silence that made him ashamed and yet exultant.

“Do you know, Chips?”

“It depends what you think he’s done.”

“I’ll tell you,” said Jan with sudden resolution, and a lift of his head as though the peak of a cap had been pulled down too far. “I had a secret when I came here, and Evan knew it but nobody else. It was a big secret — about my people and me too — and if it had come out then I’d have bolted like a rabbit. I know now that it wouldn’t have mattered as much as I thought it would then. Things about your people, or anything that ever happened anywhere else, don’t hurt or help much in a place like this. It’s what you can do and how you take things that matters here. But I didn’t know that then, and I don’t suppose Evan did either. Yet he kept a quiet tongue in his head about everything he did know. And that’s what I owe him — all it meant to me then, and does still in a way — his holding his tongue like that!”

Still Chips held his own tongue. Jan was now the prey of doubts. He had thought that a plain statement of his debt would clear the air. He had not thought that the first person he confided it to would hear it in such stony silence. Suddenly aghast, he had to ask the most crucial of questions.

“Chips ... Chips ... Did he ever tell you?”

“The very first time I saw him, our very first term!”

“Not — not about my father and — the stables — and all that?”

“Everything!”

Jan threw himself back four years.

“Yet when I sounded you at the time —”

“I told you the lie of my life! I couldn’t help myself. But this is the truth!”

Jan took it with composure, the enviable composure which had only deserted him when Evan was being slandered. It was half a minute before he made a sound, still standing there with his back to the bedroom window, and then the sound was very like a chuckle.

“Well, at any rate he can’t have told many!”

“I don’t suppose he did.” If there was doubt in Chips’s tone, Jan did not notice it at the time.

“Then he picked the right one, Chipsy, and I still owe him almost as much as I do you.”

“You owe old Heriot more than either of us.”

“Heriot! Why? Does he know?”