Shame and Consciences

9. Public speaking

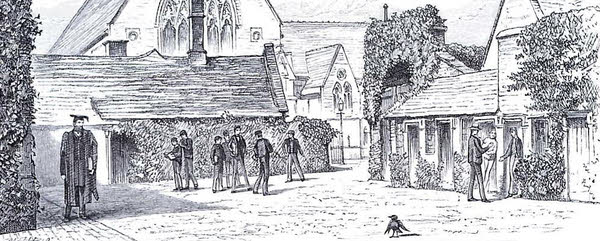

On the notice board in the colonnade was the announcement, which neither Chips nor Jan could understand, that Professor Abinger would pay his annual visit on the Monday and Tuesday of the following week. On the way up the hill to second school, they asked Rawlinson, the small fellow whom Haigh had started reviling on the first morning of term.

“Who’s Abinger?” was the reply. “You wait and see! You’ll love him, Tiger, as much as I do!”

“Why shall I?” Jan liked Rawlinson, and envied him his callous cheerfulness under oppression.

“Because he’ll get us off two days of old Haigh.”

“Don’t hustle!”

“I’m not hustling. I swear I’m not. Grand old boy, Abinger, besides being the biggest bug alive on elocution!”

“Who says so?”

“Jerry, for one. Anyway, he takes up two whole days, barring first school. That’s why Abinger’s a man to love.”

“But what does he do? Give us readings all the time?” asked Chips, one of whose weaknesses was the inane question.

“Give us readings? I like that!” Rawlinson hooted with laughter. “My good ass, it’s the other way about!”

“So we have to read to him?”

“Every mother’s son of us, in front of the whole school, and all the masters and the masters’ wives!”

“And what does he do?”

“Tears us to bits for not reading the way he likes.”

Chips went on asking questions. Jan was silent because he was more interested in the answers than he cared to show. It was an alarming prospect to a new boy with an accent which had already exposed him to some scorn. Yet his ear told him that he was by no means the only boy in the school whose vowels were broad. He was not unduly sensitive about it, and only too willing to improve. What he was more on his guard against was the outlandish word and the dialect phrase which still slipped unawares out of his mouth. But these could not affect his reading aloud . That thought calmed his fears, and he rejoiced with Rawlinson at the prospect of a break in the term’s work.

This joy was increased by the obvious exasperation of Haigh, who scarcely concealed his opinion of Professor Abinger. Many his covert sneers, and loud his laughter, as he hit on something for the Middle Remove to declaim piecemeal between them. Almost at random he chose a passage from Hans Andersen’s Fairy Tales which, to his disgust, was the standard text for this purpose. But while it was plain that he disapproved of both text and expert, he could hardly say so, and nobody was surprised when he ended with a more satisfying fling at Jan.

“Some of you fellows in Mr Heriot’s house may perhaps find time to rehearse Rutter in the few words that are likely to fall to his tender mercies. Otherwise we may trust him to disgrace us before everybody.”

Those who toadied to Haigh cast indignant glances at Jan, and one within reach dealt him a kick on the shin. Jan took it all with leaden front, for that was his only means of getting in the least bit even with Haigh. Nevertheless, on Sunday evening when, with special leave, one could sit in another’s study after lock-up, Chips and Jan had Hans Andersen open before them as they munched their way through a packet of biscuits bought with their Saturday allowance.

The elderly gentleman who opened his campaign next morning did not disappoint them. He had an admirable platform presence, an austere face, and a cascade of silvery hair. His opening remarks, in a voice like a silver bell, persuaded all his new hearers that Professor Abinger really was as distinguished as he looked. He was evidently the companion of even more distinguished men. He spoke of the statesmen and judges he had coached for the triumphs of their careers. He mentioned a certain cabinet minister as a particularly painstaking pupil. He recalled a recent experience in a ducal mansion, and let something slip involving an even more illustrious name. He seemed quite embarrassed by this indiscretion, and the Headmaster frowned into his watch, which he closed with a very loud snap.

“When I look about me in this schoolroom,” concluded Professor Abinger hastily, beaming upon the serried ranks, “and when I see the future generals and admirals, bishops and statesmen, eminent lawyers and physicians — men of mark in every sphere — even peers of the realm — who hear me now, whom I myself am about to hear in my turn — when I dip into your future far as human eye can see — then I realise afresh the very wide responsibility — the — the imperial importance — of these visits to this school!”

Mr Thrale cut short any applause or sly merriment by sternly summoning the Upper Fourth, who with much shambling of feet left their seats and trooped up to the platform. Jan had heard that forms were called in any order, and was thinking of the narrowness of his escape. He was also wondering if there was so much to fear after all from such a perfect gentleman, such a jolly old boy, when Evan Devereux passed him. And Evan’s ears were red to the tip — Evan, neat and dapper enough to stand up before the world — Evan, a gentleman if there was one in school!

The Upper Fourth huddled together on the platform, each with a fat blue volume of Andersen open at the fatal place. A nod from Mr Thrale, and the captain of the form took a step forward, threw out his chest, and plunged into one of the tales with a couple of sentences that made the rafters ring. The professor stood smiling his approval, and Mr Thrale nodded to the next boy. The successful performer sidled to the back, to be replaced by one in too great a hurry to get it over. “A myrtle stood in a pot in the window,” he had rattled off when the Headmaster exclaimed “Three o’clock!” and the performer melted away like a wraith.

“That’s the worst he does to you,” whispered Chips, who had made his usual inquiries. “It only means coming in at three for another shot.”

Meanwhile the professor was pointing out the second boy’s mistake. The first of first principles was that a distinct pause must follow the subject of any sentence. He had been preaching that doctrine here for so many years that he had hoped he need not preach it again; but perhaps he had not met his young friend before? His young friend had to confess with burning cheeks that they had indeed met before. When the point had been duly laboured, the next lad cleared the obstacle with an audaciously long pause after ‘myrtle.’

It was an obstacle at which many fell. But there were interludes which entertained the audience if not the performer. Stammerers were made to beat time and release a syllable at each beat. One timid child was conducted by the professor to the far end of the huge room and made to call out, “Can you hear me?” until the Headmaster signalled that he could. There was even a mirthful minute supplied by Devereux, of all people, who had looked self-conscious the whole time. When his turn came, Jan holding his breath for him, his reading was no worse than nervous until he came to the word ‘exhilarated.’ He said ‘exhilyarated.’ The professor asked him to say it again, his paternal smile changing into a sly and malevolent grin which filled Jan with revulsion. Evan said ‘ex-hill-yarated,’ making a mountain of the hill, and a stern voice cried “Three o’clock!” The unlucky Evan looked so wretched and crestfallen, and yet so attractive, that the professor was seen to plead on his behalf. But a still sterner voice repeated “Three o’clock!”

By the time the Upper Fourth returned to their place, Devereux was himself again and even came back smiling and with a jaunty walk, as some criminals foot it from the dock. But Jan could not catch his eyes, though his own were full of a sympathy which he longed to show but only succeeded in betraying to Chips.

“I might have known you were hustling,” Jan said to Rawlinson as they got out nearly an hour later than from ordinary second school. “I say, though, I do hate that old brute — don’t you?”

“What! When he’s coached a cabinet minister and been staying with the same old dukes and dukesses?”

“If he ever did,” said Jan, his mind poisoned by the treatment meted out to Evan. “It’s easy enough for him to stand up there scoring off chaps. I’d like to score off him!”

“Well, you wouldn’t be the first. He was properly scored off once, by a chap called Bewick in the Upper Sixth, who’d heard that bit about the cabinet minister and all the rest so often that he knew it by heart, and used to settle down to sleep as soon as old Abinger got going. So one time Jerry catches him nodding and says, ‘Bewick, be good enough to repeat the substance of Professor Abinger’s last remarks.’ So Bewick stands up, blinking, not having heard a blooming word, and begins: ‘The other day, when I had the privilege of being the honoured guest of his grace the Duke of —’ ‘Three o’clock!’ says Jerry, and they say Bewick was jolly near bunked. It was before my time, worse luck! I wish I’d heard it, don’t you? I say, we were lucky to escape this morning, weren’t we?”

By now, four of the lower forms had been polished off, and three more followed in third school, but the Middle Remove was not among them. There remained only second school on the second day — a half-holiday — and Chips had heard that much of the morning would be devoted to a sixth form competition for the Abinger Medal. He had also heard that not all the forms were always called upon, and that they stood a good chance of being missed out. But no sooner did the proceedings resume on a pink and frosty morning than the bolt fell for the Middle Remove.

The big school room seemed abnormally big as Jan looked shyly down from the platform. It seemed to hold four thousand boys, not four hundred. It felt as cold as an empty church. The Headmaster’s fingers, poising his joiner’s pencil over a school list, looked blue, and his breath was visible against his sombre gown. But Professor Abinger in black spats and mittens was brisker and more incisive that yesterday. His paternal smile broke more abruptly into the malevolent grin, his flowing mane looked merely hoary, and his silvery voice had the staccato ring of steel.

He was almost living up to Haigh’s opinion of him. The passage which Haigh had chosen was from a story called ‘The Mermaid,’ and the very first reader had to say ‘colossal mussel shells,’ perhaps a better test of sobriety than of elocution. But Abinger had him repeat it until a drunken man could have done better and the whole school was in a roar. At the back of the little knot on the platform, Jan set his teeth. He knew what he would do rather than make them laugh like that. But no one else made them laugh like that, though Buggins was asked if he had been born within sound of Bow Bells and, when he denied it, his rich accent raised a titter. Gradually the little knot melted. Jan read over and over to himself the sentences that seemed certain to fall to him. He was still doing so when Chips left his side and lurched to the centre of the platform. The poor fellow had had a bad night with his bronchial troubles, which had the same effect on his speech as a more common ailment.

“The bleached bodes of bed,” he began valiantly, and was still making a conscientious pause after the subject of the sentence when a hand fell on his shoulder.

“Have you a cold?” inquired the professor with his most sympathetic smile.

“Yes, sir,” said Chips, too shy to give his complaint its proper name.

“Then stand aside, and blow your nose,” said the professor, grinning like a fatherly fiend, “while the next boy reads.”

Jan was the next boy, and the last. He strode forward too indignant on Chips’s account to think of himself, and cut straight into the laugh at Chips’s expense. Nothing could have given him such a moral fillip at the last moment. He cried out his bit aggressively, at the top of his voice, but forgot none of the rules laid down, and felt he had come through with flying colours. He saw no smile on the sea of faces before him. Not a word came from the Headmaster on his right. Yet he was not given his dismissal, and was about to begin another sentence when Professor Abinger took the book from Jan’s hand.

“I think you should hear yourself as others hear you. Have the goodness to listen.” And he read: “The bleached bawnes of men who had perished at sea and soonk belaw peeped forth from the arms of soome, w’ile oothers clootched rooders and sea chests or the skeleeton of soome land aneemal; and most horreeble of all, a little mermaird whom they had caught and sooffercairted. There!” cried the professor, holding up his hand to quell the laughter. “What do you think of that?”

Jan stood dumbfounded with shame and rage, a graceless figure with untidy hair and a wreck of a tie and one bootlace trailing, a figure made to look even meaner than it was by the spruce and handsome old man beside him.

“What dost tha’ think o’ yon?” pursued the professor, dropping into dialect with heavy humour.

“It’s not what I said,” muttered Jan, so low that the only professor could hear.

“Not what you said, eh? We’ll take you through it. How do you pronounce ‘bones’?”

No answer, but a tightened jaw, shoulders pulled back, and a good inch more in height.

“B, O, N, E, S!” crooned the professor, showing all his teeth.

But Jan had turned into a human mule. The silence had suddenly grown profound.

“Well, we’ll try something else,” said the professor, consulting the text somewhat unsteadily. “Let us hear you say the word ‘sunk.’ S, U, N, K — sunk. Now, if you please, no more folly. You are wasting all our time.”

Jan had forgotten that, and it gave him a spasm of satisfaction. Otherwise he was by now as aware of his folly as anybody else present. But it was too late to think of it now. His head was burning, his temples throbbed, and he could not have spoken if he had tried. It would have taken a better man than Abinger to make him try, and the better man sat by without a word, pale and stern.

“I can do nothing with this boy,” said Abinger, turning to him with a tremor in his thin voice. “I must leave him to you, Mr Thrale.”

“Twelve o’clock!” said the Headmaster with ominous emphasis and, as he stabbed the school list with his joiner’s pencil, the Middle Remove returned down the gangway to their place. Jan went with them as if walking in his sleep, and Chips followed him with tears very near the surface. But as one sees furthest before rain, so Chips saw a good deal as he walked back blinking for his life. And one of the things he saw was Evan Devereux and the fellow next to him doubled up with laughter.

When Abinger’s campaign had ended with the award of a medal to the polly who had done least violence to a leading article in the day’s Times, the Headmaster stayed talking to the professor while the school filed out form by form. Three delinquents besides Jan went to the Upper Sixth classroom, where Mr Thrale habitually sat in judgement on the culprits of the day, to await their trial and execution. A crowd of the smaller fry pressed their noses to the diamond panes of the windows overlooking the school yard; the most notorious criminal case would hardly have attracted more to the public gallery of a law-court. One of the other malefactors showed Jan the slip of paper which described his crime: ‘Hornton thinks pepoiēkasi is a dative plural. I think he deserves a good flogging.’ Jan was just reading the master’s signature below when in sailed the judge and executioner in his cap and gown.

The boy who deserved the good flogging stepped forward and delivered his damning document. Mr Thrale examined it, exclaimed “So do I!”, and took his cane out of his desk. The criminal knelt down, the executioner gathered his gown out of the way, and eight slashing cuts fetched the dust from a taut pair of trousers and sent their wearer waddling stiffly from the room.

“Wasn’t padded,” whispered one of those left to Jan, who put an obvious question with a look, which was duly answered with a wink.

Meanwhile a youth in spectacles was being interrogated, and was replying promptly and earnestly, without lowering his glasses from the flogging judge’s face.

“You may go,” said Mr Thrale at last. “Your honesty has saved you. Trevor next. I’ve heard about you, Trevor. Kneel down, shirker!”

The wily Trevor knelt with apparent reluctance, writhed convincingly through the eight strokes which made half the noise of the other eight, and serenely went his way with another wink at Jan.

Jan had long since discovered that, out of his pulpit, the Headmaster was short and sharp of speech, rough and ready of humour, with a trick of talking down to fellows in their own jargon as well as over their heads in parables. “Sit down, Rutter, and next time you won’t sit down so comfortably,” he had rapped out when the Middle Remove went to construe to him early in the term. And it was next time now.

Jan, left alone in the presence, was ashamed to find himself trembling. He had not trembled on the platform in front of the whole school. His blood had been frozen then. Now it was bubbling. He was being looked at, that was all, with a look such as he had never met before, a look from wide blue eyes, with dilated nostrils underneath, and under them a mouth that seemed as though it would never, never open.

It did at last.

“Rebel!” said a voice of unutterable scorn. “Do you know what they do with rebels, Rutter?”

“No, sir.” It never occurred to Jan not to answer now.

“Shoot them! You deserve to be shot!”

Jan felt he did. This parable did not go over his head. It might have been concocted from uncanny knowledge of his inmost soul. All the potential soldier in him — the reserve whom this general alone called out — was shamed and humbled to the dust.

“You are not only a rebel,” the awful voice went on, “but a sulky rebel. Some rebels are good men gone wrong. There’s some stuff in them. But a sulky rebel is neither man nor devil, but carrion food for powder.”

Jan agreed with all his contrite heart. He had never seen himself in his true colours before, had not realised how vile it was to sulk. But now he did. The firing-party could not come too quick. But the flogging judge had sat down and was putting his cane back in his desk. Jan could have groaned. He longed to make amends for his crime.

“Thrashing is too good for you,” the voice resumed. “Have you any good reason to give me for keeping a sulky rebel in my army? Any reason for not drumming him out?”

Drumming him out! Expelling him! Sending him back to the Norfolk rectory, and from there very likely back to the nearest stables! More light flooded over Jan. He had already seen his enormity. Now he saw his life, what it had been, what it was, what it might be again.

“Oh, sir!” he cried. “I know I speak all wrong — I know I speak all wrong! You see — you see —”

Before he could explain, he broke down, and all the more piteously because now he felt he never could explain, and this hard old man would never, never understand. That is the tragic mistake of boys, to feel that they can never be understood by men!

Yet already the hard old man was on his feet again and with one gesture had cleared the throng from the diamond-paned windows. He laid a tender hand on Jan’s heaving shoulder.

“I do see,” he said gently. “But so must you, Rutter — so must you!”

10. Elegiacs

Jan was prepared never to hear the last of his outrageous conduct, and it cost him a huge effort to show his face again in Heriot’s. The quad was full of fellows, as he knew it would be, but only Sprawson accosted him. His hand flew terrifyingly up, only to fall in a hearty slap on Jan’s back.

“Well done, Tiger!” he cried in front of half the house. “That’s the biggest score off Abinger there’s been since old Bewick’s time!”

Jan, who had come back vowing that no hostility would make him blub, rushed up to his study with a fresh lump in his throat. That night at tea Jane Eyre of all people (who was splendidly supplied with all sorts of food from home) pushed a glorious game pie across the table to him, and for a few hours there was more sympathy in the air than was altogether good for someone who had made a public display of ill temper. True, a wave of even misplaced sympathy may be encouraging to one who has gone short of sympathy all his life. But a clever gentleman was waiting to counteract all that, and to undo at his leisure what Mr Thrale had done in two minutes.

No sooner had the form returned to his hall next day than Haigh made a sarcastic speech on the subject of Jan’s enormity. A glance would have shown him the signs of improved self-respect: cleaner jacket, hair better brushed, boots properly laced, tie neatly tied. But he chose not to see. He triumphantly reminded his favourites of his prophecy that Rutter would disgrace them all. But he admitted he was not sorry that the Headmaster and Mr Heriot and all the rest of the school had now seen for themselves what the Middle Remove had to put up with every day. He ended with a plain hint to the form to “knock the nonsense out of that silly bumpkin who has made us a laughing-stock.”

To all of which Jan listened without a trace of his old resentment, and then, an unusually neat figure, stood up.

“I’m very sorry, sir. I apologise to you and the form.”

Haigh looked unable to believe his eyes and ears. But he was not the man to revise judgement of a boy already labelled Poison in his mind. He could not fail, now, to note the improvement in Jan’s person and manner. All he could do was put the worst construction on it.

“I shall entertain your apology when you look less pleased with yourself,” he sneered. “Sit down.”

But Jan’s good resolutions were not to be washed away any more easily than Haigh’s rooted hostility. Though no scholar and never likely to make one now, Jan could be sharp enough when he chose. Hitherto, under Haigh, he never had chosen. What was the point of attending to a brute who despised you whether you attended or not? Yet that little old man in the Upper Sixth classroom had made it somehow seem worth while to do one’s best without sulking, even without expecting fair play, let alone reward. Jan felt a new broom at heart, determined to sweep clean in spite of Haigh. It happened to be a Virgil morning, and the new broom began by saying his repetition as he had never said it before. Perhaps he deserved what he got for that.

“I thought you were one of those boys, Rutter, who pretend an inborn difficulty in learning repetition? I only wish I’d sent you up to Mr Thrale six weeks ago!”

Yet Jan maintained his interest, and when put on to construe the hardest passage, got through without discredit. It was easy for the Middle Remove to take an interest in Virgil. Mr Haigh was an enthusiastic teacher who might have been the best in the school if he had not been a bully himself. His method in a Virgil hour was beyond reproach. If his form knew the lesson, there was no picturesque or curious information which it was too much trouble for him to bring out for their benefit. They were doing the bit in the Aeneid about the boat-race, and what Haigh (who had been in the Cambridge eight) did not know about rowing ancient and modern was not worth knowing. He could handle a trireme on the blackboard as though he had rowed one on the Cam, to the accompaniment of a running report worthy of a sporting journalist.

But let there be one skeleton at this feast, one Jan who could not or would not understand, and the whole hour might go by in unseemly duel between haughty intellect and stubborn imbecility. If all went well — and this was one such occasion — Haigh would wind up the lesson with Conington’s great translation. Jan was attending as he had never attended before when one couplet caught his fancy.

These bring success their zeal to fan;

They can because they think they can.

“Perhaps I can,” said Jan to himself, “if I think I can. I will think I can, and then we’ll see.”

Haigh had shut his book and was putting a question to the favoured few at the top of the form. “Conington has a fine phrase there, for possunt quia posse videntur. Did any of you notice how he renders that?”

The favoured few had not noticed, and looked seriously concerned about it. Nor had the body of the form who, having less to lose, were more philosophical. No one had noticed. Haigh was visibly displeased. “Possunt quia posse videntur,” he repeated ironically as he reached the dregs. And at the very last moment Jan’s fingers flew up with a Sunday-school snap.

“Well?” said Haigh on the last note of irony.

“‘They can because they think they can’!” cried Jan, and went from the bottom to the top of the form at one bound, amid a volley of venomous glances, but with one broad grin from Chips.

“I do wish I’d sent you up six weeks ago!” said Haigh. “I shall be having a decent set of verses from you next!”

Yet Jan, though quick as a stone to sink back into the mud, made a gallant effort even at his verses. But that was his last. They were much better than any previous attempt of his, but it was clear that Haigh did not believe they were Jan’s own work. Who had helped him? Nobody, they were all his own. No help whatever? No help whatever. Haigh laughed to himself, but said nothing. Jan said something to himself, but did not laugh. Now at last he might never have been through those two minutes with Jerry Thrale.

November was over and another week would finish off the term’s work, leaving ten strenuous days for the exams. Haigh could set only one more piece of Latin verses, and Chips was as sorry for his own sake as he was thankful for Jan’s. His own knack of writing elegiacs that both scanned and construed was the best in the form, and had brought him into considerable favour. Haigh’s taste in poetry was refined, and not only in Greek and Latin poetry. For translation, he set only gems of English verse, and his voice throbbed with their music as he dictated them. This was another mistake, for when his gems were inevitably mangled in the translation, he took it as a personal grievance, and the boys acquired a not unreasonable prejudice against some of the noblest poetry in the language. Chips not only revelled in the originals, but took great pleasure in hunting out the Latin words and fitting them into their proper places as dactyls and spondees.

“That’s the finest thing he’s set us yet,” he observed when Haigh had given them Cory’s Heraclitus for the last verses of term.

“It’ll be b***** fine when I’ve done with it,” Jan rejoined darkly.

“I should start on it early, if I were you. Like you did last week.”

“And then get told you’ve had ’em done for you? Thanks awfully. You don’t catch me at that game again. Between tea and prayers on Saturday night’s good enough for me — if I’m not too done after the paper-chase.”

“You’re not running the paper-chase, Tiger?”

“I am if I’m not stopped.”

“When you’re not even allowed to play football?”

“That’s exactly why.”

The paper-chase, on the last Saturday but one, is one of the events of the winter term. All the morning after second school, fags have been tearing up scent in the library. A spell of hard weather has broken in sunshine and clear skies, and by half past two almost the whole school is in the paddock by Burston Beeches to watch the start. A quarter of it, indeed, in flannels and jerseys of red or white, some trimmed with the colours of a fifteen, is taking part. Off go the two hares. Hounds and mere boys in plain clothes crowd to the gate to see the last of them and their bulging bags of scent. The twelve minutes’ lead allowed them seems more like half an hour, but at last the gate is opened and the motley pack pours through.

After a mile comes the first check of many, for snow is still lying under trees and hedges and from a distance always looks like a handful of waste paper. The younger hounds, leaving their betters to pick up the scent again, take a minute off, their laboured breath like tobacco smoke, and that master stationed nearby might almost be there to make sure that it is not. Off again to the first water jump — which everybody fords — and so over miles of open upland, flecked with scent and snow — through hedges into ditches — a pack of mudlarks now, and only a remnant of the pack that started. Now the scent takes great zigzags, now it is thick again, and here is the high road rolling back to the Upper, and if it wasn’t for the red sun in your eyes there should be a view of the hares from the top of one of the hills.

On the top of the last hill, by the white palings of the Upper Ground, there is a group of boys and masters and master’s wives to see the finish. Here come the hares, red as Indians with the sun upon their faces, rushing down that hill. They are halfway up this one, wet mud shining all over them like copper, when the first handful of hounds start up against the sky behind them.

“Surely that’s a rather small boy to be in the first dozen,” says Miss Heriot, pointing out a puppy who is running gamely by himself between the first and second batches of hounds.

“Not in any fifteen, either,” says Heriot, noticing the jersey rather than the boy, who is still a slip of muddy white on the opposite hill.

The hares are already home, to perfunctory applause. The real excitement lies in the race between the leading hounds, now in a cluster at the foot of the last hill. But half-way up the race is over, and Sprawson is increasing his lead with every stride.

“Well run, my house!” cries Heriot.

“The house isn’t done with yet, sir,” pants Sprawson. “Young Rutter’s been running like an old hound. Here he is, is the first ten!”

And here indeed is the rather small boy whom neither of the Heriots had recognised, slimmer and trimmer in his muddy flannels than in his workaday jacket and collar, more in his element, the flush on his face not only from exercise and a scarlet sky, but a flush of health and momentary happiness.

It has been one of the few afternoons of all the term that Jan will recall in later life, standing out among the weary walks with poor Chips and the hours of bitterness with Haigh. But it is not over yet. Sprawson is first back at the house. His good-natured tongue has been wagging before Jan gets there, and Jan hears a pleasant thing or two as he jogs through the quad to change in the lavatory. But why has he not been playing football all these weeks? It might have made all the difference to the Under Sixteen team, who might have beaten Haigh’s in the second round. What did he mean by pretending to have a heart and then running like this? It must be jolly well inquired into.

“Then you’d better inquire of old Hill,” says Jan, naming the doctor as disrespectfully as he dares. “It was he who said I had one, Loder, not me!”

Loder would like to smack Jan’s head again, but is restrained by the presence of Sprawson and Cave major, both of whom have more influence in the house than he. The great Charles Cave has not been in the paper-chase. He will win the Hundred and the Hurdles next term, but is not sturdy enough to shine across country. He does not address Jan personally, but deigns to mention him in a remark to Sprawson.

“Useful man for us next term, Mother, if he’s under fifteen.”

“When’s your birthday, Tiger?” splutters Sprawson from the shower-bath.

“End of this month.”

“Confound your eyes! Then you won’t be under fifteen for the sports, and I’ll give you a jolly good licking!”

But what Mother Sprawson actually gives Jan is cocoa and biscuits at Maltby’s in the market place: a most unconventional gift from a man of his standing to a new boy, who feels painfully out of place in the fashionable shop and devoutly wishes himself with Chips at their humble haunt. But it is a memory to treasure, and not to be spoilt by the fact that Shockley waylays and kicks him in the quad for ‘putting on a roll,’ and that Heriot sends for Jan for the first time since term began and gives him a severe wigging for running in the paper-chase at all, but sends him off with a compliment for running so well.

“He said he’d only been forbidden to play football,” Bob Heriot reported to his sister. “Of course I had to jump on him for that. But I own I’m glad I didn’t find out in time to stop his little game. It’s just what was wanted to lift him an inch out of the ruck. I believe he’ll turn out a sportsman in spite of us.”

“But what about his heart?”

“He hasn’t a heart, never had one and after this can never be accused of one again.”

“I wonder you didn’t go to Dr Hill about it long ago, Bob.”

“I did. But Hill wouldn’t take the responsibility of letting him play football without inquiring into his past history. That was the last thing to encourage, and so my hands are tied. They always are, with Rutter. It was the same with Haigh over his Latin verses. He wanted me to write to the boy’s preparatory school master! I haven’t intervened since. Rutter’s the one boy I can’t stick up for. He must sink or swim by himself, and I think he’s going to swim. If he were in any other form, I’d be sure. But I daren’t hold out the helping hand that I would to others.”

“I’ve often heard you say you can’t treat two boys alike.”

“But I can’t treat Rutter as I ever treated any boy before. I’ve got to keep my treatment to myself, or he’ll be suspicious in a minute. He puts me on my mettle, I can tell you! I’m not sure he isn’t putting the whole public school system on trial!”

“That one boy, Bob?”

“They all do, of course. They’re all our judges in the end. But this one is such a nut to crack, and yet there’s such a kernel somewhere. The boy has more character even than I thought.”

“Although he sulks?”

“That’s often a sign. It means at least the courage of one’s mood. But what you and I mustn’t forget is that his whole point of view is probably different from that of any fellow who ever went through the school.”

“As a straw plucked from the stables?” laughed Miss Heriot under her breath.

“Hush, Milly! No, I was thinking of the absolute adventure the whole thing must be to him, and has been since the very first morning when he got up early to look about for himself, like a castaway exploring the coast.”

“Well, I only hope he’s found the natives reasonably friendly!”

The sudden friendliness of the natives was Jan’s greatest joy, as for once he revelled in the peace and quiet of the untidiest study in the house. He was more tired than he had ever been in his life, but happier than he had dreamt of being this term. The hot-water pipes threw grateful warmth upon his aching legs, outstretched on the leg-rest of the folding chair. The curtains were drawn, the tollies burning at his elbow. On his knees lay a Gradus ad Parnassum and an English-Latin dictionary, and propped against the tolly-sticks was the exercise book in which he had taken down the English version of Heraclitus. Its beauty was lost upon him. He was too weary to try very hard, and knew that any success would only invite more suspicion. He did make a tentative effort in pencil, and ten minutes before prayers pulled himself together enough to write his eight lines out in ink.

“Let’s have a look,” said Chips as they waited for the Heriots in hall. One look was quite enough. “I say, Tiger, you can’t show this up! You’ll be licked as sure as eggs are eggs.”

“I don’t care.”

“You would care. You simply can’t get this signed tonight. I’ll touch it up after prayers and let you have it in time to make a clean copy before ten, and Heriot’ll sign it after prayers in the morning.”

By gulping down his milk and taking his dog-rock to his study, Chips was able to devote a good half hour to Jan’s verses. It was barely enough. The first hexameter began with a false quantity and ended with a grammatical blunder, the first pentameter was hopeless. Chips rectified, adapted, nudged. In the second couplet every other foot was a flogging matter.

I wept when I remembered how often you and I

Had tired the sun with talking and sent him down the sky.

Chips loved the lines enough to blush for his own respectable attempt at a Latin version, but his blood ran cold at Jan’s —

Flevi quum memini nostro quam saepe loquendo

Defessum Phoebum fecimus ire domum.

He flung himself on this monstrosity, but had to leave it at —

Cum lacrymis memini nostro quam saepe loquendo

Hesperias Phoebus fessus adisset aquas.

He did not plume himself on this. But at any rate nostro loquendo was Jan’s own gem, bad enough to distract suspicion from the superiority of the rest. This was a subtle calculation. He was conscious of it, and not as ashamed of it as such a desperately honest person should have been. He justified the means to the end, which was to save Jan a certain flogging; and he felt something very like a guilty relish at a first offence. The third couplet almost passed muster; a touch or two and it was safe. But the last hexameter would never do, and Chips replaced it by plagiarising his own line. That would have been fine, if he not come to grief over it himself.

“Excellent as usual, Carpenter,” said Haigh on Monday. “I could have given you full marks but for an odd mistake towards the end. You seem to have misread the line ‘Still are thy pleasant voices, thy nightingales, awake.’ What part of speech do you take that ‘still’ to be?”

“Adjective, sir,” said Chips, beginning to wonder if it was one.

“Exactly!” cried Haigh, with the guffaw of his lighter moments. “So you get Muta silet vox ista placens, tua carmina vivunt — ‘Thy pleasant voices are still; on the other hand, however, thy nightingales’ — meaning songs, as I told you — ‘are awake.’ Eh?”

“Yes, sir,” said Chips, more doubtfully than before.

“Have you a comma after the word ‘nightingales’ in the English line as you took it down?”

“No, sir.”

“That accounts for it! Ha, ha, ha! But it may be my fault.” He was geniality itself as he turned from the mantlepiece where he was going through the week’s verses. “Will those who have a comma after ‘nightingales’ hold up their hands?” A forest of hands flew up. “Then I’m afraid it’s your mistake, Carpenter. I couldn’t have pitched on a better object-lesson in the importance of punctuation if I’d tried.”

He turned back to the pile of verses on the mantlepiece, and the incident seemed over.

“But surely there was some other fellow did the same thing,” he said, frowning thoughtfully. “Ah! Rutter, of course! Jucundae voces tacitae sunt, carmina vivunt!”

His voice completely changed as it rasped out the abhorred name. It changed again before the end of Jan’s hexameter.

“Were you helped in this, Rutter?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Did you help him, Carpenter?”

“Yes, sir.”

There was not an instant’s hesitation before either answer. Yet the culprits’ readiness to confess their crime only aggravated Haigh. He flew into a passion.

“And you own up to it without a blush between you? And you, Rutter, expect me to believe that the same thing didn’t happen last week, when you denied it?”

“It did not happen last week, sir.”

“Silence!” Haigh roared. “I don’t believe a word you say. You’re not such a fool as you pretend to be. You saw you were found out at last, so you might as well make a clean breast of it! That doesn’t minimise your cheating, or the impudence of a brace of beggarly new boys. Do you know how dishonesty is treated in this school? I would send you both to Mr Thrale at twelve o’clock, but we don’t consider that a flogging meets this kind of case. It’s one in which all must suffer for the misdeeds of a few. I shall devise some detention for the entire form, and we’ll see if they can’t knock some rudimentary sense of honour into you!”

Black looks were showered on Chips and Jan. They knew what they were in for now, and trembled in their shoes. A message from Shockley was passed to them on a slip of paper, “I’ll murder you for this,” and the moment they were out in Haigh’s quad the storm burst.

“What the deuce do you both mean by owning up?”

“I wasn’t going to tell a lie about it,” said Jan doggedly.

“No more was I!” squealed Chips as Shockley twisted his arm to breaking point behind his back.

“Oh yes, you’re so b***** pious, aren’t you? Couldn’t do Thicksides for other people, too b***** moral and superior for that. But not above doing the Tiger’s verses and getting the whole form kept in!”

“It isn’t for getting your verses done,” cried another big fellow as he aimed a kick at Jan. “It’s for being such infernal fools as to own up!”

So much for the sense of honour to be knocked into them. It was a revelation. Jan and Chips knew that Shockley and Buggins and Jane Eyre regularly helped each other with their composition, and more than once had heard them flatly denying it to a suspicious Haigh. That code of honour in that precious trio hardly surprised them. What did shock them was that some of the nicest fellows in the form condemned the honesty that had got them all into trouble.

Chips and Jan did not question the system that had brought all this about. It did not occur to them to take their grievance to Mr Heriot, whose opinion might have been interesting. In the bitterness of their hearts they simply felt that an injustice had been done. The fury of the whole form, at being punished for the crimes of only two, was human and understandable. But they had been subtly encouraged by a master to do his dirty work for him. Could any trick be shabbier, and could anything be more demoralising? The form were supposed to instil a higher sense of schoolboy honour. What they actually did was to curse and kick you for not piling dishonour on dishonour’s head.

Haigh held his threat over all their heads until the two boys’ lives had been made a sufficient misery. He then withdrew it, and instead gave Chips and Jan a holiday task, to learn a long poem by heart and to say it to him without a mistake, on pain of further penalties, when they came back after Christmas.

11. The temple defiled

Christmas weather set in before the holidays. On the last Saturday of term, Old Boys came trooping down from Oxford and Cambridge and stood in front of their old hall fires in astonishing ties and wondrous waistcoats, patronising the Loder of the house, familiar only with the Charles Cave. But the Old Boys’ football match could not take place. The ground was thick with snow, and a swept patch proved as hard and slippery as the slide in Heriot’s quad. This slide was an authorised institution, industriously swept by the small fry under the supervision of old Mother Sprawson, who sent more than one of them down it barefoot as a remedy for the chilblains which they had rashly pleaded as an excuse for shirking their duty.

On the Sunday, morning chapel was dominated by the Old Boys’ presence. But before dinner they had all dispersed, and by second chapel the school had returned to business as usual. The first lesson was the story of Naaman and his leprosy, and from it the Headmaster took the inspiration for his sermon.

“Your bodies are the temple of God,” he began, “and are not to be defiled.” What exactly he had in mind he did not spell out in so many words.

“In the struggle between purity and impurity of thought and deed lies for many of you, perhaps for most of you, one of the first decisive turning-points of life. Acquaintance with your own constitution and the functions of life, combined with knowledge of the fatal consequence of sins of impurity, can alone be trusted as a safeguard.”

But by now only the youngest and most innocent of his listeners could have failed to understand. What he meant by the sin of impurity was what a fellow did, by himself, with his own right hand. Five minutes later, for he kept his sermons short, the Headmaster ended:

“Leprosy was chosen by God to mark the curse of sin by a visible vileness in the body. Suppose that every secret sin came out in leprous spots upon us, that our foreheads and faces bore the dead white mark of the sin within. What a ghastly revelation there would be; for the very best amongst us would have brought home to him, in a way he never had before, the secret curse of sin in the world. However much the rush of True Life would overmaster it, surely a great horror would come upon him, as he felt his own flesh deaden and reflect the struggles which hitherto had gone on silently in his heart; and when he saw all round the ghastly evidence written in every human form, the presence of sin would be a reality more than he could bear.”

Jan was accustomed by now to being stirred by what this fierce little man pronounced from the pulpit, and he tried to listen with care. Today, the second Sunday after their encounter in the Sixth Form classroom, he listened with unusual care. The consistent message of these sermons boiled down to a demand. It might at root be a demand for the team-work required of a soldier, it might be a demand for a decent and honourable way of life. The message was mounted, it need hardly be said, in a godly frame, designed for the listener who at least pretended to piety. But ignore that frame, and the message could equally appeal to the impious. For all his impiety, Jan had no objection to team-work or to a decent and honourable way of life, as he saw them; quite the reverse.

But today’s sermon irritated him, for he could not see that it carried any message for him. He could not see why the so-called impurity castigated by that stern old voice should detract from a decent way of life. To Jan, it was no sin, but a relief, a consolation for the buffets of life, a norm. So it was too, from all that he had deduced and from what old Jerry clearly assumed, to practically every other boy in the school. Jan did not often think deeply, but this thought occupied him throughout the final hymn.

As he left the chapel another thought was bothering him, and to tackle it he stood aside while the chattering hordes dispersed. The Bible might insist that leprosy was the visible mark of sin. But in Norfolk, shortly before term had started, there had been a sermon by a visiting preacher, a missionary from darkest Africa where, it appeared, leprosy abounded. Was sin, then, so much more prevalent in Africa than in England, where leprosy was all but unknown? No, it was not. Leprosy, the missionary had made plain, was a disease, just like mumps or measles but much worse. Was it the victim’s fault? No, it was not, any more than mumps or measles were. The Headmaster was backing the wrong horse today, or rather two wrong horses.

Still deep in reflection, Jan picked his slow way along the slippery pavement to Heriot’s, remembering that he had agreed to go for a walk with Chips. That put a further thought into his head, which made him chuckle dourly. If leprous patches were the reward of impurity, then only the likes of Chips would remain unblotched. The sermon seemed to have put a similar thought into the disreputable head of Shockley, who was hovering, hands deep in the trouser pockets that were allowed to older boys, outside the gate which led from the street into the quad. With him, as usual, was Buggins.

As Jan passed the studies, Chips opened his window above, stuck out his head, and called down, “Wait there for me, Tiger! I’m coming!”

“Small chance of him coming!” Shockley remarked to Buggins, none too quietly. “Too pi and too young to come.” Buggins obligingly guffawed.

As Chips closed his window, Jan boiled with internal rage, but he held his peace. Chips might not have heard that cruel crudity or, if he had, might not have understood; whereas if Jan made a scene, Chips would undoubtedly ask why. In a minute Chips emerged from the gate, swaddled in overcoat and muffler, and joined Jan in the street. They headed for the open country, and the moment they were out of earshot of the dangerous pair, Chips showed that he had indeed heard but not understood.

“Tiger, what did Shockley mean? I know they call me pi, but what did he mean that I’m too young to come?”

Jan groaned silently.

“Well —”

Am I my brother’s keeper? he asked himself, for the language of chapel and divinity lessons was willy-nilly rubbing off on him. Chips was younger than he was. His voice had not yet broken but, from the glimpses of his nakedness which Jan had had in the lavatory when changing after fives, it soon would. Half of Shockley’s comment might already be untrue. The other half, though, was valid. Chips was undoubtedly a pious innocent. But he could hardly pass his whole life in pious innocence. Somebody, at some point, had to enlighten him. If Jan ignored his question now, or laughed it off, the answer might soon be supplied more hurtfully by Shockley & Co with their crude insinuations, or even by Joyce with his untrammelled vocabulary. Chips might be an old ass, but he was Jan’s only companion. Yet more to the point, Jan was Chips’s only companion. As such, Jan had a duty. In perhaps the first conscious act of responsibility in his life, he took the plunge.

“Well — did you understand what Jerry was talking about in chapel?”

Chips blushed bright scarlet. “Yes,” he said, after a long pause.

“Well —” Jan suddenly realised that, in this realm, his own vocabulary was limited to what he had picked up in the stables. He had not the faintest idea of the words which gentlemen used — pious well-bred gentlemen, that is, as opposed to the Shockleys or Joyces of this world — when talking about these things, assuming they ever did talk about them. He had to fall back on such mother wit and delicacy as he could muster.

“Well, ‘coming’ means — it’s a low word for — for what happens when — when you do what Jerry was talking about. As you finish doing it. I don’t know if you know about that. And I’m sorry, I don’t know the proper word for it.”

Chips was still bright red. “Ejaculation,” he muttered through his teeth.

The word was completely new to Jan, but he had enough Latin in him by now to see that it fitted.

“Then you do know! How do you know, Chips? Have you — done it yourself?”

“No! My father told me about it. And told me not to do it. He said it made you go blind.”

“That’s rot, Chips, absolute rot.” It did not cross Jan’s mind that it might be tactless to contradict Carpenter senior so bluntly. “If it was true, almost every boy in the school would have gone blind long since. Almost every man in the country. But they haven’t. Any more than they’ve got Jerry’s leprosy. After all, I’m not blind, am I?”

He could have bitten his tongue off, but it was too late to retract. Chips was gaping at him, open-mouthed in raw astonishment.

“Tiger! How did you — well, learn about it?” he asked at last.

“Oh, I — heard about it at my last school.”

That was truth, but not the whole truth. The older boys at the National School in the suburbs of Middlesbrough had indeed talked about it, but Jan had first heard of it at an early age in the stable, and there, a year or so ago, it had also been demonstrated to him. He had hidden himself in the hayloft one evening to indulge, out of his father’s sight, in another illicit practice. He was just filling his pipe when he heard Ted the groom climbing the ladder to his own retreat. The end of the hayloft was divided off by a crude wooden partition into a little cubicle where Ted occasionally slept when there was a sick horse to tend or even — so rumour told — when there was not. On this occasion, being surprised and curious, Jan had abandoned his designs on his pipe and peeped cautiously through a crack in the partition. What he saw he imitated; not only there and then, but regularly thereafter in his truckle bed in the coachman’s cottage. But this was a story not for Chips’s ears.

“Tiger, why do you do it?”

“Because — well, because they say it’s the next best thing to doing it for real. It makes you feel so good.”

“Good? How can you say that? It’s a sin!”

That irritated Jan, just as the Headmaster had irritated him from the pulpit. “It’s only a sin if you believe in sin. It doesn’t hurt you, it doesn’t hurt anyone else. It might hurt God, if you believe in God. But I don’t. So I don’t believe this is a sin either.”

Jan had never consciously reasoned in that way before, not even in chapel just now, and the words had flowed out unrehearsed. Hearing them from his own lips, he was quite impressed, and emboldened.

“There’s no God, Chips,” he blurted out. “Not the way I see it. There’s nobody up there to help us along, or to kick us down. There’s only people. Other people — good ones helping us along, bastards kicking us down. And there’s us. We have to help ourselves along. And shagging helps me along, shagging and thinking of ...”

Jan shut his mouth, regretting his impulse, conscious that for once he had said too much, dimly aware that this philosophy could be seen as revolutionary and subversive, determined — almost too late — not to reveal who or what he thought about while shagging. But Chips had not even winced at ‘bastards’ or at ‘shagging.’ Maybe he had never heard that last word before, even though it was regular school slang; but he could hardly miss its meaning. Instead, he was looking Jan full in the face again, open-mouthed once more. They had stopped abreast of a field entrance, and after a full minute Chips turned round and leant on the gate, breathing hard, his breath steaming the air, gazing across the fields where misty winter twilight was already muting the white tones of the landscape. A pair of crows, in bad-tempered conversation nearby, made up their differences and flew off together in apparent amity. Jan waited with apprehensive patience, growing steadily colder, and after another five minutes Chips turned back to him, the faintest of smiles on his face.

“Better not let anyone else hear that, Tiger,” he said mildly. “Specially not Jerry. Let’s get home.”

They walked back to Heriot’s without another word between them. Shockley and Buggins were as usual hanging around the door into the studies, and favoured Chips with pitying leers. But Chips, rather than scuttling hastily past as he normally would, stopped and gave them a tight-mouthed and inscrutable look, so unexpected from him that it momentarily wiped the leers from their faces. Chips abruptly turned his back on them and marched with determination to his study, and Jan heard him lock his door.

A hour later there was a knock at Jan’s own door, and Chips stuck his head in. He seemed elated now.

“Thank you, Tiger,” he said simply. “Shockley was wrong!”

With that, he was gone, leaving Jan at first bewildered, then relieved and amused as Chips’s meaning sank in, and finally thinking more highly of the old ass than he had ever thought before.

12. A merry Christmas

It remained exceptionally cold. The fire in hall was twice its usual size. The study pipes became too hot to touch, yet remained a mockery until you had your tollies going as well and every chink stopped up. Sprawson himself appeared to rely more than ever on his surreptitious flask, but as he never displayed the usual symptoms except before a select audience, and could convincingly sham sober whenever necessary, his antics were more amusing than thrilling. It was Sprawson who, after lock-up on the last night, lit up the slide in the quad with tollies and kept the fun fast and furious until the school bell rang sharply through the frost, and the quad dispatched its quota of glowing faces to prize-giving in the big school-room.

The break-up concert had been given there the night before, but this final function was more exciting, with the Headmaster beaming behind a barricade of emblazoned volumes, the new school list in his hand. It was fascinating to learn the new order, form by form, and stirring to hear and swell the thunders of applause as the prize-winners steamed up for their books. Crabtree was the only one whom Jan clapped heartily. He was top of his form as usual, as was Devereux lower down the school, but Jan was not going to be seen applauding Evan unduly. When it came to the Middle Remove, Chips could not keep still and even Jan sat up with a tight mouth. On their places depended their chance of moving out of Haigh’s clutches. Jan was higher than he expected to be, but Chips was higher still, with the Shocker and Jane Eyre just above him, and Buggins was the lowest of the group.

“I wish to blazes old Haigh would hop it in the holidays, Tiger,” said Buggins on their way back through the snow. “You and I may have another term of the greaser if he don’t.”

Jan said little, but not because he was surprised at the sudden friendliness of an inveterate foe. Everyone was friendly on the last day. Jane Eyre was profuse in his hospitality at tea. Even Shockley himself was civil. As for Chips, he had already presented Jan with a silver pencil-case out of his journey-money. But Jan himself had never been more glum than when all the rest were packing, and looking up trains, and talking about their people and all they were going to do at home, and making Jan realise that he had no home and people to call his own.

That was perhaps an unfair way of putting it, even to himself. But Jan had some excuse. In all those thirteen weeks he had received no more than three letters from the rectory. This shortage had become notorious. He had soon given up looking for letters, and when one did come for him it lay on the window-sill until somebody told him it was there. This had supplied the chivalrous Shockley with yet another taunt. And the occasional letter never enclosed a money-order or heralded a hamper on its way by rail. Jan had brought so little with him by way of eatables or pocket-money that a time had come when he flatly refused Chips’s potted meat because he saw no chance of ever having anything to offer in return.

These of course had been minor troubles, but they were the very ones a fellow’s people might have foreseen and remedied, if they had cared for a moment to do the thing properly. But all they had done was to write three times to remind him of their charity in doing the thing at all, and to impress upon him what a chance in life they were giving him. That again was only Jan’s view of their letters, and was perhaps as unfair as his whole instinctive feeling towards his mother’s family. But it was strong enough to make him feel the outcast when he came down on the last morning, in his unaccustomed bowler, to the meat breakfast provided in the gas-lit hall, and out into the chilling dawn to squeeze into an omnibus because he had failed, back in the middle of term, to take Chips’s advice and order a trap well in advance.

Jan’s journey was all across country, and long before the end he had shaken off the last of his schoolfellows travelling in the same direction. He knew few of them even by name, yet he was sorry when they had all been left behind. They were the last links to a place where, he now realised, he felt more at home than he was ever likely to feel in the holidays. Eventually he reached a bleak rural station where there was nothing to meet him. Leaving casual instructions about his luggage, he walked up through the snow to the rectory.

The rectory was the nearest point of the thatched and straggling hamlet of which it was also the manor house. It stood in its own park, a mile from the vast flint church in which a handful of people were lost at its two perfunctory services a week. The rector was in fact more squire than parson, though he conducted a forbidding form of family prayer every weekday. He happened to be the first person whom Jan saw in the grounds, on the sweep of the drive between house and lawn. On the lawn itself a lady and a number of children were busy making a snowman, and the old gentleman, watching with amusement from the swept gravel, cut for the moment a sympathetic figure. Jan had to pass close by him and felt bound to report his return, but no one seemed to see him. He had been hovering for some moments almost at the rector’s elbow, too shy to announce himself, when the lady came smiling across the snow.

“Surely this is Jan, papa?” she said, at which the rector turned round.

“Why, my good fellow, when did you turn up?”

Jan explained that he had just walked up from the station. There was an awkward interval while his grandfather took open stock of him, with a quite different face from the one which had beamed upon the children in the snow. The lady made amends with a kind smile.

“I’m your Aunt Alice, and these little people are all your cousins. We’ve come for Christmas, so you’ll have plenty of time to get to know each other.”

Clearly there was no time then. The children were already clamouring for their mother to return to the snowman, and she went back with a speed which told its tale. Jan did not know whether to go or stay, until the rector observed, “If you want anything to eat they’ll look after you indoors.” Jan accepted the dismissal thankfully, though he felt its cold abruptness. But the old man had been curt and chill to him from their first meeting, and throughout these holidays it remained clear that he took no sort of interest in the schooling which, on a whim, he was providing. This was nothing new, and Jan would not have minded for a moment if he had not caught such a very different old fellow smiling on the other grandchildren in the snow.

Jan’s grandmother went to the opposite extreme by taking too much notice of him, and embarrassing notice at that. Her duty, she felt, was to supplement the school in turning him into a gentleman. She searched through her spectacles for the first term’s crop of visible improvements. She found few, but plenty of surviving blemishes, each of which she berated. Mrs Ambrose was one of those formidable old ladies who have to say exactly what they think, whatever the time or place. Jan could hardly come into a room without being told to wipe his boots properly, without his fingers and nails being inspected, or his collar or hair. He seldom sat at table without hearing that he had used the wrong fork or that knives were not made to enter mouths. Again he would have been less resentful if the other grandchildren had not been present and their equally glaring misdemeanours consistently overlooked.

But he disliked the other grandchildren chiefly because Aunt Alice was the one person present whom he really did like, and they would never let him have a word with her. They were whining, selfish, demanding little wretches. Their father spent most of his time shooting with another uncle, a military one, thus leaving the burden of discipline to Aunt Alice. Now and then Jan did get her to himself, and her gentleness might have sweetened his holidays if her eldest had not celebrated the New Year by nearly putting out Jan’s eye with a stone contained in a snowball. Usually good-tempered and long-suffering with his small cousins, on this occasion Jan told the offender exactly what he thought of him, in schoolboy terms.

“I don’t care what you think,” retorted the child, who was quite old enough to be at a preparatory school but had refused to go to one. “Who are you to call a thing ’caddish’? You’re only a stable-boy — I heard Daddy say so!”

Jan promptly committed the unpardonable sin of ‘bullying’ by smacking the head of “a boy not half your size.” In futile self-defence he repeated what the boy had called him. “And so you are!” cried Aunt Alice, her tears as hysterical as her child’s. That cut Jan to the heart, for he could not see that, where her children were concerned, she lost her reason. He only saw it was no use trying to justify his conduct. Everybody was against him. His grandfather threatened him with a horse-whipping. His grandmother said it was “high time school began again,” and Jan broke his sullen silence to agree, wholeheartedly and rudely.

He had to spend the rest of the day in his room and to endure a further period of ostracism until Captain Ambrose, the military uncle, returned from a few days away and heard from the ladies of Jan’s heinous offence. Being no admirer of his younger nephews and nieces, he took a seditious view of it, which he reinforced by tipping the offender half a sovereign.

“Thank you very much, sir!”

“Not sir, please! Call me Uncle Dick. And don’t thank me — you deserve it, for I’m afraid you’ve been having a pretty poor time. But take my advice. Don’t treat little swabs spoiling for school as though you’d actually got ’em there. They’ll get there in time, thank God, and I wouldn’t be in their little breeches then! By the time they reach your age they might be wiser. How old are you, by the way?”

“Fifteen. And eight days,” said Jan a trifle bitterly.

“And eight days? So your birthday was on —”

“December the twenty-seventh.”

“And nobody marked it? Or even mentioned it? I didn’t know.” He pointedly refrained from saying that his parents must have known. “I’m sorry about that. Let me make amends.”

Another half-sovereign changed hands. He smothered Jan’s thanks by repeating, “I’m afraid you are having a poor time of it. Found something good to read?”

“I’m not reading.” Jan showed him his book. “I’m learning The Burial-March of Dundee.”

“That sounds cheerful! So they give you holiday tasks at your school?”

“Not exactly. This is something special.”

Under friendly pressure he explained what and why. Uncle Dick’s sympathetic attitude was making another boy of Jan, and his views on Haigh and his vindictive punishment verged on the treasonable.

“I never heard of such a thing in my life! A master spoil a boy’s holidays for something he’s done at school? It’s monstrous, if not illegal, and if I were you I shouldn’t learn a line of it.”

“I’ve learnt very near every line already. And there’s a hundred and eighty eight altogether.”

“A hundred and eighty eight lines in the Christmas holidays! I should like to have seen any of our old Eton beaks try a game like that!”

“He said he’d tell Jerry if either of us makes a single mistake when we get back.”

“Let him! Thrale’s an Old Etonian himself, and one of the very best. Let your man go to him if he likes, and see if he comes away without a flea in his ear. Anyhow, you shan’t hang about the house to learn another line while I’m here. Out you come with me, and try a blow at a bird!”

So Jan did after all have a few congenial days, in which he slew his first pheasant and acquired a devotion to his Uncle Dick, who might miss a difficult shot but never missed an opportunity of encouraging a youngster. That was precisely what Jan needed, even more than open sympathy and affection. Captain Ambrose told his mother they would make something of the boy if they did not bother too much about trifles, and wished his own leave could last all the holidays. But he had to go about the middle of January, a few days after Aunt Alice and her party, and after that Jan had a dreary week to himself.

He spent much of the time in solitary prowling with a pipe and tobacco bought out of Uncle Dick’s tips. He had learnt to smoke in his stable days and, unlike most boys, genuinely enjoyed it. At any rate a pipe passed the time, if less challengingly than a gun. But he was not allowed to shoot alone, and his grandfather never took him out or showed the slightest interest in his life under the rectory roof. But his grandmother made up for that, with such incessant fault-finding and calling-to-order that, by the end of the holidays, Jan was longing for the privacy of his unsightly little study, and for a life free of old ladies and little children.

He was therefore anything but overjoyed, the day before he was due to return to school, when a telegraph-boy tramped up through the heavy snow with a telegram to say that the railway was blocked and the start of term had been postponed. Some four hundred such telegrams had been hurriedly sent to the four quarters of Britain, and all but one were doubtless received with rapture. Jan received his with a smile, but a very strange smile for a boy on the brink of his second term, which is notoriously as hard as the first but without its redeeming novelty.

13. The New Year

Shockley, Eyre and Carpenter found themselves promoted to the Lower Fifth. Rutter and Buggins had failed to get their remove, the line being actually drawn at Jan, who was left official captain of the Middle Remove. Chips bewailed their being separated during school hours, but Jan was not so much depressed by that. What scared him was the prospect of spending most of the time in the same class as Evan Devereux. It was bad enough to be despised by Haigh, but how much worse to be despised in front of Master Evan! Expecting to make a bigger fool of himself than ever, he spent the first morning in an angry glow, feeling Evan’s eyes upon him, wondering what reports would go home about him now, forgetful of the ordeal hanging over Chips and himself.

Chips had not forgotten, but had written to Jan about it in the holidays, without receiving any reply. The moment they met up again, he had taxed him about it but had got no further. Jan’s dry and secretive manner, part-product of his Yorkshire blood, could be very irritating when he chose, and it was impossible to tell whether or not he was word-perfect in The Burial-March of Dundee. Chips, who had left nothing to chance, was word-perfect, and Jan was his only anxiety when he went to Haigh’s after second school on the first day and found his friend awaiting him with impassive face.

“Now, you boys!” cried Haigh when the three of them were in his hall. “Carpenter, begin.”

“‘Sound the fife and cry the slogan —’” began Chips more fluently than most people read, and proceeded without a hitch for sixteen unfaltering lines.

“Rutter!” interrupted Haigh.

Jan made no response.

“Come, come, Rutter,” said Haigh, unexpectedly encouraging, as though the holidays had softened him. “‘Lo! We bring with us the hero’” — and, after a pause, in the old snarl — “‘Lo! We bring the conquering Graeme’?”

Even this prompting drew nothing out of Jan.

“Give him another lead, Carpenter.” Chips continued, more nervously but no less accurately, down to the end of the first long stanza.

“Now then, Rutter. ‘On the heights of Killiecrankie’ — come on, my good boy!”

Haigh was evidently so flattered and mollified by Chips’s obedience that Jan was to be given every chance. But he did not take it.

“Have you learnt your task, or have you not?”

No answer even to that.

“Sulky brute!” Haigh was pardonably angry now. “Do you remember what was to happen if you failed to pay for your dishonesty last term? You remember, Carpenter?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Carpenter, you may go. You’ve taken your punishment in the proper spirit, and I shall not mention your name if I can help it. You, Rutter, will hear more about the matter from Mr Thrale tomorrow.”

“Thank you, sir,” said Jan, breaking silence at last, not with impertinence but devout sincerity. Haigh took him by the shoulders and ran him out of the hall in Chips’s wake.

Chips was miserable about the whole affair. He was sure his friend would be instantly expelled, or so publicly degraded that he would perversely sulk his way to expulsion. The worst of it was that Jan was so uncommunicative. He would not explain himself any more than he had done to Haigh. The only consolation was that nobody else knew about the latest developments, and Chips was not the man to discuss with others what Jan refused to discuss with him.

Next day, in his new form in the Lodge, there was no more absent mind than Chips’s. It was after second school that the day’s delinquents were flogged by the Headmaster before the eyes of anyone who liked to peer through the diamond panes of his class-room windows. But, as Chips passed by on his way out of school, there were no spectators outside and no judge or executioner within. In response to an anxious question, Chips was told by a youth who addressed him as ‘my good man,’ that even old Thrale didn’t start flogging on the second day of term. Instead of being relieved, he was only more depressed, having heard that really serious cases were not taken in this public way, but privately in the Headmaster’s sanctum. Chips went back to Heriot’s full of dire forebodings and, after looking vainly into Jan’s study, shut himself in his own. He was still sitting there when Jan’s unmistakable slipshod step brought him to his door.

“Tiger!” he called under his breath, with a world of anxiety in his voice.

“What’s up now?” asked Jan, coming in with a rough swagger which Chips had seen only once or twice before.

“That’s what I want to know. What’s happened? What’s going to happen? When have you got to say it by?”

“I’ve said it.”

Chips might have been knocked down by the proverbial feather.

“You’ve said The Burial March to Haigh?”

“Without a mistake. I’ve just finished saying it.”

“But when on earth did you learn it, man?”

“In the holidays.” Jan grinned uncouthly at Chips’s stupefaction.

“Then why the blazes couldn’t you say it yesterday?”

“Because I wasn’t going to. He’d no right to set us a holiday task of his own like that. He’s a right to do what he b***** well likes to us here, but not in the holidays, and he knew it jolly well. I wanted to see if he’d go to Jerry. I thought he dursn’t, but he did, and you bet the old man sent him away with a flea in his ear! He never got on to me all second school, and he looked really sick when he told me that Mr Thrale said I was to be kept in till I’d learnt what I’d got to learn. It was the least he could say, if you ask me” — Jan grinned complacently — “and Haigh didn’t seem any too pleased about it. So then I said I thought I could say it without being kept in, just to make him sit up a bit. And by gum it did!”

“But he heard you, Tiger?”

“He couldn’t refuse, and I got through without a blooming error.”

“But didn’t he ask you what it all meant?”

“No fear! He’d too much sense. But he knows right enough. Instead of him sending me up to the old man, it was me that sent him, and got him the wigging he deserved!”

By this time Chips was in a fever of excitement, too demonstrative for Jan’s outward liking, much as it might cheer his secret heart.

“Tiger!” was all Chips could cry as he wrung the Tiger’s paw. “Oh Tiger, Tiger, you’ll be the hero of the house when this gets known!”

“Don’t be a daft hap’orth.” Jan did not have to watch his dialect in Chips’s company, not now. “It’s nobody’s business but yours and mine. It won’t do me any good if it gets all over the place.”

“It won’t do you any harm!”

“It won’t do me any good. Haigh knows. That’s good enough for me, and you bet it’s good enough for Haigh.”

Chips respected Jan all the more because he was not bidding for respect.

“But who put you up to it?”

He was already cross with himself for being so docile about the whole business, and it would be a comfort to know that the Tiger had not thought of such a counterstroke himself. And the Tiger was perfectly candid, repeating Captain Ambrose’s views and singing his praises with an enthusiasm worthy of Chips.

“Ambrose? What’s his initials?”

“R. N., I think. They call him Dick.”

“R. N. it is!” cried Chips, reaching for the little row of green and red Lillywhites on his shelf. “He’s the cricketer — must be — did he never tell you so?”

“We never talked about cricket,” said Jan indifferently. “But he used to wear cricketing ties, now you remind me. One was red and yellow —“

“M.C.C.!”

“— and another was half the colours of the rainbow.”

“That’s the I.Z.! And here’s the very man as large as life!” He read the entry out loud. “‘Captain R. N. Ambrose (Eton), M.C.C. and I Zingari. With a little more first-class cricket would have been one of the best bats in England; a rapid scorer with great hitting powers.’ I should think he was! Why, he made a century in the Eton and Harrow — it’s still mentioned when the match comes round. And I’ve got to tell you about your own uncle!”

“It only shows what he is, not to have told me himself,” said Jan, infected for once with Chips’s enthusiasm. “I knew he was a captain in the Rifle Brigade, and a jolly fine chap, but that was all.”

“Well, now you should write and tell him how you took his advice.”

“I’ll wait and see how it turns out first,” replied Jan with native shrewdness. “I’ve had my bit of fun, but old Haigh has the term to get on to me more than ever.”

Yet on the whole Jan had a far better term than he expected. Haigh, if he loathed him more than ever, at least did not loathe him so blatantly. Though from time to time he displayed his old contempt, he no longer gave it free rein. Instead of loading Jan with elaborate abuse and unnecessarily exposing his ignorance, he systematically ignored him, treating him as if he seldom existed and was not to be taken seriously when he did. All of which suited Jan very well, without hurting him in the least. He often caught Haigh’s eye upon him, and something in its wary glance gave the Tiger quite a tigerish satisfaction. He hardly thought the man was frightened of him (though in a sense he was), but he did chuckle over the thought that Haigh would be as glad to be shot of him as he of Haigh.

He had a double chuckle when, by thinking for himself, he would occasionally go to the top of the class at a bound, as in the scarcely typical case of possunt quia posse videntur. It was not only Haigh’s face that was worth watching as he gave the devil his due, but also Master Evan’s, who was quick to learn but slower to apply, who was nearly always top, and who hated being displaced. Jan was sore to the soul about Evan Devereux, now that they worked together but seldom spoke, nor ever went up and down the hill together, though that was when Evan was at his best and noisiest with a gang of his own cronies.

Jan was unreasonably jealous and bitter about that, but at the same time grateful to Evan for holding his tongue. His policy, evidently, was better never speak to a chap than speak about him, and one day at least his silence was more golden than speech. Buggins, who was rather too friendly with Jan now that they were the only two Heriot’s boys in the form, described the old Tiger as his ‘stable companion.’ Evan happened to hear. His eyes caught Jan’s and dropped at once, and he blushed. That was enough for simple Jan. Lack of friendliness was forgiven. Evan was as sensitive about his secret as he was himself.