Shame and Consciences

Preface

My three-part Scholar’s Tale and A Time were set at Yarborough School in my own day, which was long enough ago. This is another story about Yarborough, but set in the even more distant past, far beyond living memory. It is not really my own work, and what lies behind it demands a deplorably but necessarily long explanation.

Ernest William Hornung (1866-1921), the son of an émigré from

Transylvania, was a prolific British novelist, befriended by Rudyard Kipling and H. G. Wells

and married to Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s sister. While he never quite matched his

brother-in-law’s success with Sherlock Holmes, he did create the equally memorable figure

of Raffles the gentleman crook; who has proved equally long-lived, for almost all the Raffles

books are still in print. Here, however, we are concerned not with them but with one of

Hornung’s later novels, Fathers of Men, published in 1912, reprinted only once

in 1919, and now virtually forgotten (but available online at

https://archive.org/stream/fathersmen01horngoog#page/n8/mode/2up).

Its setting is the Yarborough School of 1880 to 1884, when Hornung himself was there as a

boy.

Victorian school stories were almost two a penny, but few are memorable. Tom Brown’s Schooldays (1857), the best known, sets out to preach a very deliberate sermon and is populated by rather cardboard characters. Kipling’s Stalky & Co (1899), arguably the best written and full of lively portraits, is a very deliberate satire. Fathers of Men, it seems to me, has much deeper insights than either. Nor am I alone in this view. Hornung himself felt it the best of all his works. His biographer Peter Rowland (Raffles and his Creator, 1999) tends to agree. Reviewers praised it highly: to quote two verdicts, it is ‘a fresh and penetrating study of that eternal problem — the human boy,’ and it is ‘serious, compassionate, absorbing, and deeply intelligent.’ It seems well worth resurrecting.

Nonetheless there are difficulties. The first half, with its leisurely setting of the scene, is undeniably slow. The second half, where the real action lies, does in places resort to over-worn conventions and stock figures such as the untutored prodigy of a cricketer. On top of that, the style can be horribly convoluted and wordy; to quote a not untypical sample, ‘The anxious submissiveness of the really good boy, with the subtle flattery conveyed by implicit obedience to an overbearing demand, had so far mollified the master; but Jan did not avail himself of the clemency extended.’ Language of this kind hardly makes for easy reading.

But perhaps the biggest problem is that, in Victorian times as for long after, school stories, almost by definition, had to be wholesome and uplifting. Orthodoxy and prudery forbade any serious challenge to convention. Individual boys, then as now, undoubtedly questioned the accepted religious and moral code, but few dared question it in public. No more could novelists allow them to question it in print. And however well-observed their characters, whatever other complications might tangle their heroes’ lives, these authors invariably left one unmentionable element unmentioned. They could not admit that boys were aware of, let alone preoccupied with, anything so sordid as sexuality. In that sense if in no other, their tales are neither whole nor real.

Why, then, resurrect this story on a gay site? The answer is intriguing. Hornung, though placidly married, was gay. There can be little doubt about it. As a grown man he befriended boys. The relationship between Raffles and his sidekick Bunny is latently homosexual. And Hornung deeply admired Oscar Wilde. Indeed when he christened his only son, at the very moment of Wilde’s downfall and disgrace, he gave him the name of Oscar. This was as clear a sign of his sympathies, and at the time almost as scandalous, as a father in 1945 naming his child Adolf.

What is more, it seems that Fathers of Men was originally neither orthodox nor ‘wholesome.’ Hornung sent an early draft for criticism to a close friend, who pounced on unspecified episodes and dialogue ‘which seemed likely to spoil the book.’ Hornung’s arm was twisted, and he spent wretched months making the necessary changes. Many years later this same critic was praised by a third party for saving Hornung’s reputation. The very guarded language in which all this is recorded strongly suggests that the offending passages were not only sexual in nature but, given the context, homosexual.

We will never know exactly how that early draft ran. But a few hints have survived the alterations; possibly, indeed, they were deliberately allowed to survive. These I have developed into a new thread, matched as best I can to the texture of the original and woven into the fabric of the tale at places where there seem to be obvious gaps. Because the topic, so revolutionary for those days, would hardly be picked out in too garish a shade, Hornung’s expurgated thread was surely subdued in colour. So too, therefore, is my replacement thread. It is too much to expect it to follow the original pattern, but I hope that it may restore a touch of reality and wholeness to what is both a good story and an instructive social commentary on its period.

I have also done a great deal of tinkering. Two complete chapters, which contribute nothing to the development of the plot or of the characters, have gone by the board. Throughout, short passages have been added here and subtracted there. In particular, I have adjusted almost every sentence to make the style more simple and succinct. As a result the overall length has shrunk by a quarter, with the loss of no substance and, I hope, a gain in readability. But I have hardly touched the words which Hornung puts into the mouths of his characters. Such parlance as ‘I say, chaps, I had a jolly ripping time in the hols’ may make present-day toes curl. But in it we hear the authentic voice of the Victorian public-school boy. A critic of the day, a teacher by trade, castigated standard school stories — Tom Brown included — because ‘no boys ever talked as their boys did,’ but he heaped praise on Hornung for ‘reproducing boys’ talk as it actually is.’

On the subject of boys’ talk: then as now, it surely included swear-words, and Hornung, in his quest for authenticity, would surely have liked to include them. But while this would raise few eyebrows today, his publisher could hardly have allowed it then. In line, therefore, with what was the utmost permissible a century ago, I have toned down with asterisks the few swear-words that I have ventured to introduce.

In short, I have tried to retain not only the essence of the story but its period flavour too; for it is very much a period piece, and so it ought to remain. This raises minor problems. Because education at places like Yarborough was dominated by the classics, there are constant references to Greek and Latin. There are snippets from current Gilbert and Sullivan songs. There is period slang and school slang which (except where it is too obscure) I have retained and sometimes explained. But such details are fine brush-strokes which hardly affect the overall painting: if they escape the reader who does not know Patience from Pinafore or a dactyl from a spondee, it does not matter a hoot. What is much more important is to steer clear of reading modern nuances into period language. The present-day connotations of ‘queer’ and ‘gay’ lay, at that date, far in the future. When a boy called someone ‘straight,’ he meant honest and honourable. A fag was no more than a junior boy doing menial jobs for a prefect. If, to the house-master, ‘boys are dearer than men or women,’ that does not make him a paedophile.

A greater difficulty for some non-British readers may be the cricket which looms large in the second half of the tale. Passing mentions of the long-departed Lillywhite’s Cricketers’ Annual and the still-surviving Wisden’s Cricketers’ Almanack can be taken in their stride. But there are whole pages of ball-by-ball commentary. Drastic pruning here would not only destroy a fascinating insight into the game at a time when there were only four balls to the over and serious bowlers could still bowl underarm, but it would also spoil the story. I have therefore retained these passages. Here too a knowledge of the rules is not essential, but to those who wish to know more I once again commend the excellent website of the Seattle Cricket Club (https://www.seattlecricket.com/history/crick.htm) and especially its page on Explaining Cricket to Americans. And, after all, is not baseball a cousin — some would say a descendant — of cricket?

The school’s organisation, which may be another puzzle to non-Britons, deserves explanation. It comprised three distinct groupings, by house, by form, and by games. Every boy belonged to a house — there were twelve of them scattered around the town — where he lived and ate and which claimed his loyalty. He joined the school at, usually, thirteen or fourteen, and was graded academically by ability alone. A form might therefore contain boys of very different ages. The sequence of forms, as far as it concerns us, is laid out in Chapter 2. It is important to remember that, as is still general in Britain, the Sixth Form, and specifically the Upper Sixth, was the highest, corresponding in level to the American Twelfth Grade. Prefects (known officially as praepostors, unofficially as pollies) were drawn from the Upper Sixth, and boys left at eighteen if they had not left before. There were three terms in a year (Winter, Easter and Summer). The normal weekday timetable ran thus: school prayers, first school (that is, lessons), breakfast, second school, dinner, games, third school (except on half holidays), tea, private work, house prayers.

Games (fives, athletics, and above all football and cricket) were organised partly on a house and partly on a school basis. For each game, every house had its own two teams — All Ages and Under Sixteen (or sometimes Under Fifteen) — which competed for the inter-house challenge cups. Football and cricket were played on three grounds, the Lower, the Middle and the Upper. New boys would be placed in teams on the Lower or Middle and progress, if they were good enough, to the Upper. The pinnacles of achievement were the Fifteen and the Eleven (graced with capital letters), which were the school’s first teams at football and cricket respectively. With football, however, Yarborough had not yet adopted the Rugby rules and still played its own version of the game.

The novel’s original title was based, of course, on the proverb that the child is father of the man. The new slant to the story suggests a new title, drawn from George Herbert’s poem which I have woven into the fabric in Chapter 31.

A word too on the Headmaster’s sermons. Hornung’s apparent quotation from one in Chapter 30 is in fact of his own composition, but the extracts I have inserted into four other chapters are the genuine article, drawn from the old man’s published works.

As we look back from the relatively liberated and egalitarian present (the emphasis being on relatively), we must allow for much social change. Yarborough has long been a pioneering and liberal school. Not perhaps when it was founded in 1584; but it is pioneering today, it was so sixty years ago in my own time, and it was so — markedly more than the Rugby of Tom Brown — at the date of this story. But even the most liberal public school of a hundred and thirty years ago preached what seems to us a very stern morality and tolerated what seems to us a great deal of injustice. Four historical facts should above all be borne in mind:

- Society was stratified by class and caste — contempt for him who ventured above his station.

- School life was regulated by harsh discipline — the cane for the rule-breaker and the slacker.

- Education was permeated by religion — a foretaste of hell-fire for him who, in the Headmaster’s eyes, transgressed.

- The gravest transgression of all was sexual activity between males — unmitigated shame, the full stigma of the moral leper, upon him whose conscience surrendered to such lust. Lust it was invariably taken to be, for same-sex love lay beyond the comprehension of Victorian authority.

One final factor touches me personally: that the story’s superstructure is built upon a tangibly solid foundation of reality. The school is so meticulously described that, although it remains anonymous throughout, it is instantly identifiable to anyone who knows Yarborough (which is but my own disguise for its real name). Many, maybe most, of Hornung’s characters were likewise based on actual people, although naturally he changed their names. Bob Heriot and Jerry Thrale, so sympathetically portrayed, were real men and his real mentors. So too, the other side of the coin, was the unspeakable Haigh, who is never favoured with a first name. Chips Carpenter with his bronchial problems, his poor eyesight, and his passion for cricket, was Hornung himself, who in real life left Yarborough early because of his asthma.

Above all, some aspects of Jan Rutter, the hero of the tale, were borrowed from a boy who was a contemporary of Hornung’s and in the same house. I could name him, but will not. In due course this boy’s son also went to Yarborough and ultimately became a master there. He was still a master in my own day, and a most endearing and memorable one. It was only recently that I learned of this connection; too late, sadly, to discuss it with him before he died. But, now that I do know, I count it a privilege to have sat at the feet of Jan’s son.

I am grateful to Andy who has designed the title picture, and more than usually indebted to those who have vetted drafts for style and comprehensibility: Chris with British, Neea and Ben with non-British eyes. And, as always, I have been wonderfully supported in every way by Hilary and by Jonathan.

26 January 2005

1. Behind the scenes

There were two new boys this term in Robert Heriot’s house. Over dinner, and afterwards in his study, he encouraged them both to talk. The results could hardly have been more different. One said too much, while the other kept a stubborn mouth tight shut. The garrulous one paraded, as well as an exuberant knowledge of cricket, all the signs of a careful upbringing — he cracked polite little jokes with Miss Heriot, he opened the door for her after dinner, and he thanked her for the evening when it was over. His companion, by contrast, uttered no more than morose monosyllables, and finally beat a sullen retreat without a word.

Heriot saw the pair to the boys’ side of the house. He was filling his pipe as he returned to the jumble of books and papers and the paraphernalia of many hobbies that reduced his study to a box-room in which it was difficult to sit down and impossible to lounge. His sister, perched on a stool, was busy mounting photographs at a worm-eaten bureau.

“I do hate our rule that a man mayn’t smoke in front of a boy!” exclaimed Heriot, gratefully puffing his pipe. “And I do wish we didn’t have the new boys on our hands a whole day before the rest!”

“I’d have thought there was a good deal to be said for that.”

“You mean from the boys’ point of view?”

“Exactly. It must be such a plunge for them as it is, poor things.”

“It’s the greatest plunge in life. But here we don’t let them make it. We think it kinder to put them in an empty bath and then turn on the cold tap — after first warming them at our own fireside! It’s always a relief when these evenings are over. The boys are never themselves, and I’m no better. We begin by getting a false impression of each other.”

Heriot was keeping a narrow eye on his sister. He was a lanky man, many years her senior. whose beard had turned grey in his profession, and his shoulders round. But there was still a restless energy about him. Spectacles in steel rims twinkled at every abrupt turn of his grizzled head; and the sharp look through the spectacles was kindly rather than kind, just rather than compassionate. He could see further than most through a brick wall, his boys agreed, and not one of them ever contemplated taking liberties with him.

“I liked Carpenter,” said Miss Heriot as she spread paste on the back of a print.

“I like all boys until I have reason to dislike them.”

“Carpenter had something to say for himself.”

“There’s far more character in Rutter.”

“He never opened his mouth.”

“It’s his mouth I go by, as much as anything.”

Miss Heriot laid her print carefully on the album page and smoothed it with an unfeminine handkerchief. She did not reply.

“You didn’t think much of Rutter, Milly?” he pressed.

“I thought he had a bad accent and —“

“Go on.”

“Well, to be frank, worse manners!”

“Milly, you’re right, and I’m going to be frank with you. Let the next print wait a minute. I like you to see something of the fellows in my house, and it’s only right that you should know something about them first — in this case, what I don’t intend another soul in the place to know.”

His sister turned to look at him as he planted himself in typical British attitude, back to the fireplace.

“You can trust me, Bob.”

“I know I can. That’s why I’m going to tell you what neither boy nor man shall learn through me. What type of lad does this poor Rutter suggest to your mind?”

There was a pause.

“I hardly like to say.”

“But I want to know.”

“Well then. I’m sure I couldn’t tell you why, but he struck me as more like a lad from the stables than anything else.”

“What on earth makes you think that?” Heriot spoke quite sharply in annoyed surprise.

“I said I couldn’t tell you, Bob. I suppose it was an association of ideas. For one thing, when I first saw him he had his hat on, and it was far too large for him, and crammed down almost to those dreadful ears! I never saw any boy outside the stable yard wear his hat like that. Then your hunting was the one thing that seemed to interest him at all. And I certainly thought he called a horse a ‘hoss’!”

“So he put you in mind of a stable-boy, did he?”

“Well, not exactly at the time, but the more I think about him, the more he does.”

“That’s very clever of you, Milly. Because it’s just what he is!”

“Of course you don’t mean it literally?”

“Literally.”

“I thought his grandfather was a country parson?”

“So he is. A rural dean, in fact, in Norfolk. But the boy’s father was a coachman, and the boy himself was brought up in the stables until six months ago.”

“The father’s dead, then?”

“He died last winter. The mother died giving birth to the boy. It’s the old, old story. She ran away with the groom.”

“But her people have taken an interest in the boy?”

“They cut her off when she eloped. They never set eyes on him till his father died.”

“Then how can he know enough to come here?”

Heriot smiled as he pulled at his pipe. His sister, as he had hoped, was showing the same sympathetic interest as he felt himself. There was nothing sentimental about the Heriots; they could discuss most things frankly on their merits, and the school was no exception. It was wife and child to Robert Heriot, it was the vineyard in which he had laboured lovingly for thirty-five years. But he could still smile as he smoked his pipe.

“Our standard isn’t high,” he said. “To some critics it’s the scorn of the public-school world. We don’t go in for making scholars. We go in for making men. Give us the raw material, and we won’t reject it because it doesn’t know the Greek alphabet, not even if it was fifteen on its last birthday! That’s our system, and I support it through thick and thin. But it lays us open to worse types than escaped stable-boys.”

“This boy doesn’t look fifteen.”

“Nor is he, quite. But he has a head on his shoulders, and something in it too. Apparently the vicar near Middlesbrough, where he came from, took an interest in him and got him as far as Caesar and Euclid, for pure love.”

“That speaks well for the lad.”

“It appealed to me, I must say. Then he’s had a tutor for the last six months; and neither Yorkshire vicar nor Norfolk tutor has a word to say against his character. He should be placed quite high in the school. I’d be glad to have him in my own form, to see what they’ve taught him between them. I’m interested in him, I confess. His mother was a lady, but he never saw her in his life. Yet it’s the mother who counts in the making of a boy. Has the gentle blood been hopelessly poisoned by the stink of the stables, or is it going to run clean and sweet? It’s a big question, Milly, and it’s not the only one.”

Through the summer tan of Heriot’s face, in the eager eyes behind the glasses, shone the zeal of that rare expert to whom boys are dearer than men or women.

“I’m glad you told me,” said Miss Heriot at last. “I might have been prejudiced if you hadn’t.”

“My one excuse for telling you. No one shall ever know through me. Not even Mr Thrale, unless some special reason should arise. The boy shall have every chance. He doesn’t even know that I know, and I don’t want him ever to suspect. It’s quite a problem, for I must keep an eye on him more than on most, yet I daren’t be down on him, and I daren’t stand up for him. He must sink or swim for himself.”

“I’m afraid he’ll have a bad time.”

“I don’t mind betting Carpenter has a worse.”

“But he’s so enthusiastic about everything!”

“That’s a quality we appreciate. Boys don’t, unless there’s prowess behind it. Carpenter talks cricket like a Lillywhite, but he doesn’t look a cricketer. Rutter doesn’t talk about it, but his tutor says he’s a bit of a bowler. Carpenter beams because he’s got to his public school at last. He’s got illusions to lose. Rutter knows nothing about us, and probably cares less. He’s here under protest. You can see it in his face, and the chances are that he’ll be pleasantly disappointed.”

Miss Heriot returned to her photographs, her mind full of the two boys who, for good or ill, had come to live under their roof. Was her brother right? She had heard him sum up characters before, on equally brief acquaintance, and had never known him wrong. He had a wonderfully fair mind. Yet the active boy who might be stimulated into thought was always nearer his heart than the thoughtful boy who needed goading into physical activity. Now, she felt, he was being unsympathetic to the one who had more in him than most small boys did, and biased in favour of the other by his romantic history and social handicap. To him, this material was novel as well as raw, and so doubly welcome to the craftsman’s hand. To her, a sulky lout never appealed, however cruel his background.

But she would really see very little of them until they rose to the Sixth Form table over which she presided in hall. Now and then they might have headaches and be sent to the private side for rest and quiet. But she would never be in real touch with them until they were at the top of the house, shy and correct, with few words (but not too few) and none too much enthusiasm, like all the other big boys. That drew a sigh from her.

“What’s the matter?”

“I was thinking that both these boys have more individuality than most. How much of that will be left when we turn them out of the mould in five years’ time?”

“I know where you get that from!” Heriot sounded almost exasperated. “You’ve been reading these trashy articles that every wiseacre who wasn’t at a public school thinks he’s qualified to write! That we melt boys down and turn them all out of the same mould, like bullets. That we destroy individuality, that we reduplicate a type which thinks the same and speaks the same, which has all the same virtues and the same vices. As if character really could be changed! As if we could boil away a strong will or an artistic bent, a mean soul or a saintly spirit, even in the crucible of a public school!”

She had her own views on that. Not every boy who passed through the house was the better for it. She had seen the weak go under, into depths she could not plumb, and the selfish ride serenely on the crest of a wave. She had seen an unpleasant urchin grow into a more unpleasant youth. She had seen inferiority made doubly inferior when it wore that precious but misleading label, “Product of a public school.”

“But you admit it’s a crucible. And what’s a crucible but a melting-pot?”

“A melting-pot for characteristics, but not for character! Take the two boys upstairs. In four or five years one will have more to say for himself, I hope, and the other will leave more unsaid. But each will be the same self, even though we’ve turned a first-rate groom into a second-rate gentleman.”

He gave the sudden infectious laugh which his house and form were never sorry to hear. Knocking out his pipe into a Kaffir bowl, the gift of some exiled Old Boy, he went off to bid the two new boys good-night.

2. Change and chance

Rutter had been put in the small dormitory at the very top of the house. The other dormitories, in one of which he had left Carpenter on the way upstairs, consisted of two long rows of cubicles. But here under the roof was a square room with a dormer window in the sloping side, a communal dressing table beneath it, a double wash-stand at each end, and a cubicle in each of the four corners. Cubicle was not the school word for them, according to the matron who came up with the boys, but ‘partition,’ or ‘tish’ for short. They were about five feet high, contained a bed and a chair apiece, and were merely curtained at the foot. They reminded Rutter of stalls in a stable.

He noted everything with an eye that was unusually sardonic for fourteen, and unusually alive to detail. He took a grim look at himself in the mirror. It was not a particularly pleasing face, with its sombre expression and stubborn mouth, but it looked brown and hard, and acute in a dogged way. For a second it almost smiled at itself, but whether in resignation or defiance or with a touch of involuntary pride in his new circumstances, even he could hardly say. It was certainly with a thrill that he read his own name over his tish, and then the other boys’ names over theirs. Bingley was next to him, Joyce and Crabtree were the other two. What would they be like? What sort of faces would they bring back to the mirror on the dressing table? Rutter was not conscious of an imagination, but somehow he pictured Joyce as large and lethargic, Crabtree as a humorist, and Bingley as a bully of the Flashman type. He had just been reading Tom Brown’s Schooldays, and wondered if the humorist would be man enough to join him in standing up to the brutes, and whether pillow-fights were still the fashion. Probably not, because Master Evan had never mentioned them. But then Master Evan, when he last had seen him, had still been at preparatory school. Now he had gone on to public school, and there at Winchester he might have found things quite different.

The new boy undressed with an absent mind. He was wondering what it would have been like if he had been sent to Winchester himself, and there encountered Master Evan on equal terms. He had never done so much wondering in his life. He found a copy of last term’s school list in the dormitory and took it to bed with him, and lay there wondering more.

It started with the masters. So most of them were Reverends, were they? He grimaced to himself. Then came the boys, listed by form from the top downwards. First was the Upper Sixth, then the Lower Sixth, then one curiously called the Remove, and in the Remove was friend Joyce of the corner opposite. Next came the Fifths — three of them — with Crabtree top of the Lower Fifth. Clever fellow, then! The bully Bingley was no doubt notoriously low in the school. The Middle Remove came next, and through each column of strange names he read religiously, with a fascination he could not have explained. He had got down, by way of the Upper Fourth, to the Middle Fourth when a familiar name took his breath away.

Heriot came in to find a face paler than it had looked downstairs, but a good brown arm and hand lying out over the coverlet and clutching a Midsummer List. The muscles of the arm were unusually developed for so young a boy. Heriot saw them relax under his gaze as he stood over the bed.

“Got hold of a school list, have you?”

“Yessir,” said Rutter with a slurring promptness that did not savour of the schoolroom. Heriot turned away before he could wince, but unluckily his eyes fell on the floor, strewn with the litter of the new boy’s clothes.

“I like the way you fold your clothes!”

“I beg your pardon, sir, but where am I to put them?”

It was refreshingly polite. But, again, the beg-pardon opening was not the politeness of the schoolboy.

“On this chair,” said Heriot, picking them up. The boy would have leapt out of bed to do it himself, but he was too shy, and too shy to protest or even to thank. Next moment he had good reason to be bashful. Mr Heriot was holding up a broad and dirty belt, and without thinking had cried, “What’s this?”

Rutter could not answer for shame, and Heriot had time to think.

“I can sympathise,” he said with a chuckle. “In the holidays I wear one myself. But we mustn’t betray each other, Rutter, or we’ll neither of us hear the last of it! I’ll sign you an order for a pair of braces in the morning.”

“I have them, sir, thanks.”

“That’s all right, then.” Heriot was still handling the belt as if he longed to buckle it round his own waist. Suddenly he noticed the initials ‘J. R.’

“I thought your name was Ian, Rutter?”

“So it is, sir. But they used to call me Jan.”

Heriot waited for a sigh, but the boy’s mouth, typically, was tight shut. “Well, good night, Jan, and a fair start to you! The matron will put out the gas at ten.”

The lad mumbled something. The man looked back to nod, and saw him lying as he had found him, still clutching the list, but with his face now as deep a colour as his arm.

“Have you come across any names you know?”

“One.”

“Who’s that?”

“He won’t know me.”

They were the sullen answers that had made so bad an impression downstairs, but they were strangely uttered, and Rutter no longer lay still.

“He must have a name,” said Heriot, coming back into the room.

No answer.

“I’m sorry you’re ashamed of your friend,” he said, laughing.

“He’s not my friend, and —” The boy shut his mouth again.

“I think that’s very likely. What’s in a name? The chances are it’s only a namesake after all.”

He turned away with no sign of annoyance or further interest, but was stopped by another mumble from the bed.

“Name of Devereux,” he made out.

“Devereux, eh?”

“Do you know him, sir?”

“I should think I do!”

“He’ll not be in this house?” Rutter was holding his breath.

“No, but he got my form prize last term.”

“Do you know his other name?” It was a tremulous mumble now.

“I’m afraid I don’t. No, wait a bit! His initials are either E. P. or P. E. He only came last term.”

“He only would. But I thought he was going to Winchester!”

“That’s the fellow. He got a scholarship and came here instead, at the last moment.”

The new boy said nothing when the matron put out the gas. He was lying on his back, eyes wide open and lips compressed, just as Heriot had left him. It was almost a comfort to know the worst. And now that he knew it, beyond possibility of doubt, he was wondering whether it need be the worst after all. It might prove the best. He had always liked Master Evan. That was as much as he dared admit right now, though he should have put it more warmly. But, whether Evan Devereux should cut him dead or shake his hand, he now knew the best or the worst. And what a good thing that this lean old man, with his kind word and his abrupt manner, could not possibly know his secret or be aware of his hopes and fears.

It was very quiet in the top dormitory, but sleep did not come easily. Rutter wondered what it would be like when all the boys came back. He wondered what it would have been like if Master Evan had been in that house, in that little dormitory, in the tish next to his own. Master Evan! He had never thought of him as anything else, much less addressed him by any other name. What if it slipped out at school? It easily might, far more easily and naturally than ‘Devereux.’ After all, ‘Devereux’ would sound like profanity, in his own ears and from his own lips.

He grinned involuntarily in the dark. It was all too absurd. He had had plenty of opportunity to pick up the language of the class to which he had just been elevated. ‘Too absurd’ would certainly be their way of describing his situation now. He tried to see it from that point of view, for he had a wry humour of his own. He must not magnify something which nobody else might think twice about. A public school was a little world in which two boys in different houses, even if of the same age, might seldom or never meet. Days might pass before Evan as much as recognised him in the throng. Once he did, he might refuse to have anything to do with him. But then — but then — he might tell the whole school why.

“He was our coachman’s son at home!”

The coachman’s son heard that betrayal as though it had been shouted out loud. He felt a thousand eyes on his face. He knew that he lay blushing in the dark. It took all his will to calm himself by degrees.

“If he does,” he decided, “I’m off. That’s all.”

But why should a young gentleman betray a poor boy’s secret? Rutter was the stable-boy again in spirit. He might have been back in his truckle bed in the coachman’s cottage at Mr Devereux’s. Yes, he had always liked Master Evan. Events of a lifetime’s friendship came back to mind, in shoals. Evan had been the youngest of a large family, and that after a gap, so that in one sense he was an only child. Often he had needed a boy to play with, and often Jan Rutter had been scrubbed and brushed and oiled to the scalp in order to fill the proud position of that boy. He remembered the instructions with which he was sent off from the stables. ‘Mind not to do this, mind not to say that.’ It was difficult not to do or say them when you had always to keep minding. Still, he also remembered hearing the ladies and gentlemen passing complimentary remarks on him, together with whispered explanations of his manners.

In the beginning, he was dimly aware, there had been little to choose between Evan and himself, but later, for a time, the gulf became very wide. He recalled with shame a phase when Master Evan had been forbidden, and not without reason, to have anything to do with Jan Rutter. There was even a cruel thrashing from his father for using language learnt from the executioner’s own lips. Characteristically, Jan had never quite forgiven him for that, though he had been a kind father on the whole. Later, the boy about the stables had acquired more sense. The eccentric vicar of the local church had taken him in hand and spoken up for him, and nothing was said if Jan bowled to Master Evan after his tea, or played a makeshift game of racquets with him in the stable yard, so long as he kept his tongue and his harness clean. So, in recent years, the gulf had narrowed again.

That gulf, moreover, had always been spanned by quite an array of bridges. In the beginning Evan used to take his broken toys to Jan, who was a fine hand at rigging ships and soldering headless horsemen. In return — he now recalled those condescending payments with a twisted smile — Jan was given anything without value or broken beyond repair. Jan was also an adept at roasting chestnuts and potatoes on the potting-shed fire, a daring manipulator of molten lead, a comic artist with putty, and the pioneer of smoking in the hayloft. Those were the days when Evan was suddenly forbidden the back premises, and Jan was set to work in the stables when he was not at the local school.

Years elapsed before cricket drew the boys together again, by which time Jan had imbibed some wisdom. Finding himself to be a natural left-hand bowler who could spoil an afternoon by dismissing his opponent too soon, he was sensible enough to lose the knack at times, only to recover it when Evan had made all the runs he wanted. As Jan was not much of a batsman, there was seldom any bad blood. Indeed Jan always saw to that, in whatever they did together, for he had developed a devotion to Evan, who could be perfectly delightful to one companion at a time, and when everything was going well. Jan was a lone wolf of limited experience, and from his lowly vantage point the only young gentleman he knew, even if a slightly flawed specimen of the species, easily became a paragon and a hero. From there he had become the object, the necessarily distant object, of physical yearning. Jan was ready to admit it, now, and wondered if this mysterious feeling was what people called love.

And then things had happened so thick and fast that it was hard to remember them in order. The central fact was that, last February, Rutter the elder, that fine figure on the coach box with his bushy whiskers and his bold black eyes, had suddenly succumbed to pneumonia after a bout of night-work. The son of an ironmaster’s coachman in Middlesbrough awoke to find himself the grandson of an East Anglian clergyman whose ancient name he had never heard before, but who sent for the lad in hot haste, to make a gentleman of him if it was not too late.

That move, from the raw red suburbs of a raw upstart industrial town to the most venerable of English rectories in a countryside almost unchanged since the Conquest, Jan Rutter did not appreciate. He preferred the fashionably fussy architecture of his former surroundings to the complacent antiquity of his new home. Here he was prejudiced. This was the very atmosphere which had driven his mother to desperation. Her blood in him rebelled again, though he was too young to trace the reason. He only knew that he had been happier in a modern saddle-room than he would ever be under mellow tiles and medieval trees.

In the midst of this unhappiness, the tutor and the strenuous training for a public school came as some relief. But the odd lad took a pride in showing no pride at all in his new status. The new school and the new home were all one to him. He had not been consulted about either. He recognised that he was under an authority he was powerless to resist. But he could not be grateful to those who took him in from a sense of cold duty, who never so much as mentioned his father’s death or breathed his mother’s name. He had inherited something of his parents’ pride.

He had heard of public schools from Evan, and even envied him his coming time at one. But when his own time came so unexpectedly, Jan had hardened his heart and faced the inevitable as callously as any criminal. But now, equally unexpectedly, he was about to see again the one human being he really wished to see again. True, Jan had heard nothing from Evan since the end of the Christmas holidays; but then they had never written to each other in their lives. And the more he thought about it, the less Jan feared the worst from their meeting tomorrow or the day after. Not that he counted on the best, not that a prospect recently unwelcome had suddenly become welcome. Master Evan as an equal was still an inconceivable and inaccessible figure, and the whole future remained grey and grim. But at least there was a glint of excitement in it now, a vision of depths and heights.

On this his first night at a public school, his thoughts swooped, now up, now down. It did not even cross his mind, full of images of Evan though it was, to try the recipe for sleep that he had discovered a year or so back. The only sounds were the muffled ticking of his one treasure, the little watch under his pillow, and the harsh chimes of the church clock. He heard it strike eleven, then twelve. But life was more exciting, when he finally did drop off, than Jan Rutter had dreamt of finding it when he went to bed.

3. Very raw material

The sun was barely up when Jan swung himself out of bed and padded to the water closet next door. He had been impressed, last night, to find so modern a facility here. The Norfolk rectory had enjoyed no more than earth closets. So too, less fragrantly, had the coachman’s cottage at Middlesbrough. The only water closet he had encountered before was in the Devereuxs’ house, which Master Evan had once introduced him to.

Relieved, he put on the trousers without pockets and the Eton collar, black jacket and tie ordained by the school authorities. He was particularly offended by the rule about trouser pockets. Those in his jacket were already so full that there was barely room for his incriminating belt. But he rolled it up as small as it would go and crammed it in, to be hidden away in his study when he had one. He then marched downstairs. Most of the household were presumably still in bed and asleep. But Jan was naturally an early riser, he was curious about his new surroundings, and convention meant little to him.

The lead-lined stairs, worn bright as silver at the edges, took him down to a short tiled passage. At one end was a green baize door which, he remembered from last night, led to the private side of the house. At the other end, he found, was the boys’ hall, of good size, with one very long table under the windows and two shorter ones either side of the fireplace. On the walls hung portraits of the great composers, under the clock was a shelf with two silver challenge cups, and under the shelf was a piano, but he took no interest in them. What did attract him was the line of open windows, solid blocks of sunlight and fresh air. In front of one a maid was busy with her wash-leather, and she accosted Jan cheerily.

“You are down early, sir!”

“I always am.” Jan was looking for a door into the open air.

“You’re not like most of the gentlemen, then. They leave it to the last moment, and then they have to fly. You should hear ’em come down them stairs!”

“Is there no way out?”

“Into the quad, you mean?”

“That’s the quad, is it? Then I do.”

“Well, there’s the door, just outside this door. But Morgan, he keeps the key, and I don’t think he’s come yet.”

“Then I’m going through that window,” and through it he went.

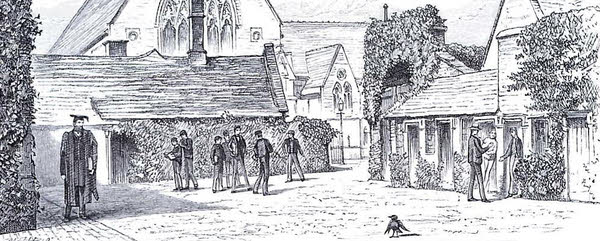

From the way she leant out to watch him, the maid seemed to fear that he was running away on his very first morning, before his house-master was astir. Had he intended to, he would have been thwarted. Heriot’s quad was a gravel plot entirely enclosed, at the back by the house, on the right by the boys’ studies, on the left by buildings next door, and ahead by two strange structures, open-ended under gothic arches. Jan had never seen the like, but he had picked up enough about public schools to guess that they were fives courts. To their right was an alley ending at a formidable spiked gate which offered the only way of escape, if Jan had been minded to escape. But nothing was further from his mind. Indeed there was a gleam in his eyes and a flush on his face which had not been there the evening before.

The studies interested him most. Small lattice windows, on two floors, pierced a wall of ivy like portholes in a ship’s side. Each had its little window box, in some of which still drooped the withered remnant of a brave display. Jan was indifferent to flowers, or to anything in life that made for mere beauty, but he peered with interest into one of the ground-floor studies. There was little to be seen beyond his own reflection broken into bits in the diamond panes, one eye level with his nostrils, an ear sprouting grotesquely from his chin. Between him and the windows was a border of shrubs, behind iron palings bent by the bodies and feet of generations and painted green like the garden seats under the wall opposite. On the whole, and in the misty sunlight of the fine September morning, Jan liked Heriot’s quad.

“You’re up early, sir!”

It was not the maid this time, but a bearded man-servant he had seen the previous night. Jan made the same reply as before, and no secret of how he had got into the quad. He would like to have a look at the studies, he added, and Morgan, with a stare and a smile quite lost on him, showed him round.

They were absurdly, delightfully, inconceivably tiny, the studies at Heriot’s. Each was considerably smaller than a dormitory tish, and the saddle-room of Jan’s old days would have made five or six of them. But they were undeniably cosy and attractive, as compact as a captain’s cabin, as private as a friar’s cell, and far more comfortable than either. Or so they might seem to the normal boy about to possess a study of his own, with a table and two chairs, a square of carpet as big as a bath-towel, a bookshelf, pictures and ornaments to taste, a flower-box for the summer term, hot-water pipes for the other two, and above all a door to shut against the world.

But Jan Rutter did not have the instincts of a normal boy. He had been brought up too uncomfortably to know the value of comfort, and too much in the open air to appreciate the merits of an indoor sanctuary. He lacked all artistic impulse, and the attempts at artistry visible in the studies left him thoroughly unimpressed.

“Is it true,” he asked, “that every boy has one of these holes?”

“Quite true,” replied Morgan, staring. “You didn’t say ‘holes,’ sir?”

“I did,” declared Jan, enjoying his accidental hit.

“You’d better not let Mr Heriot hear you, sir, or any of the gentlemen either!”

“I don’t care who hears me,” retorted Jan boastfully. After all, he had come to school against his will, and this was his first chance to air a not unnatural antagonism.

“You wait till you’ve got one of your own, with a nice new carpet and tablecloth, and your own family portraits and sportin’ picters!”

“At any rate I know a horse from a cow” — Jan was examining a sporting print — “and wouldn’t hang up rot like that!”

“You let Mr Shockley hear you! You’ll catch it!”

“I probably will,” said Jan grimly. He followed Morgan into an empty study and asked if it was likely to be his.

“Not unless you take a pretty high place in the school. It’s only the top dozen in the house that get these front studies upstairs. You’ll get one at the back, most likely, and be glad if it’s not downstairs, where everybody can see in and throw in stones.”

Jan felt he had not made a friend in Morgan. Yet he was more impressed with what he had seen than his queer temperament allowed him to show. Little as their furnishings appealed to him, there was something very attractive about this system of separate studies. It appealed, and intentionally so, to a boy’s spirit of independence, which happened to be one of his stronger points. He could, moreover, imagine a happy closeness between two real friends in one of these little dens. He brought a brighter face to the breakfast table than he had shown the night before. Heriot glanced at it with an interested twinkle, but whatever he may have guessed he kept to himself.

After breakfast Rutter and Carpenter went out with orders signed by Heriot for a school cap apiece, and saw the long old-fashioned country street for the first time in broad daylight. It gave the impression of a street with nothing behind it on either side, the remnant of a vanished town. Nothing could have been more solid than the fronts of the stone houses, nothing more startling than the glimpses of vivid meadow-land like a backdrop close behind. The caps were on sale at the shop of the cricket professional, a former star (whose glorious career was at Carpenter’s finger tips) now sadly run to seed. The caps were black and not comely, a cross between a cricket cap and that of a naval officer, with the school badge in red above the peak. Jan chose the biggest he could find, and crammed it over his skull as though he was going out to exercise a horse.

The day was fully occupied with the examination designed to put the right boy in the right form. There were three papers in the morning alone. But there was a short break between each, much of which Carpenter spent in boring Rutter with appreciative comments on the decorations of the great schoolroom where the examination was held. There were forty-two new boys, some of them quite small, some hulking fellows of fifteen or more. None, surely, was more impressed than Carpenter by the reproductions of classical statuary or by the frieze of literary figures, and none less than Rutter. To pacify his companion he did cast a look at them, but it was the same look as he had cast into the studies before breakfast.

The two had more in common when they compared notes on the various papers.

“I didn’t mind the Latin grammar and history,” said Jan, whose spirits seemed quite high. “I’ve had my nose in my grammar for the last six months, and you only had to answer half the history questions.”

“But what about the unseen?” asked Carpenter.

“I’d done it before,” said Jan, chuckling, “and not so long ago, either!”

Carpenter looked at him. “Then it wasn’t unseen at all?”

“Not to me.”

“You didn’t think of saying so on your paper?”

“Not I! It’s their look-out, not mine.”

Carpenter pointedly made no comment. It was the long break in the middle of the day, and they were on their way back to Heriot’s for dinner. “I wish they’d set us some verses,” he said at last. “They’d be my best chance.”

“Then you’d be a fool if you took it,” put in a good-humoured lout who had joined them in the street.

“But it’s the only thing I can do at all decently. I’m a backward sort of ass at most things, but I rather like Latin verses.”

“Well, you’re another sort of ass if you do your best in any of these piffling papers.”

“I see! You mean to make sure of a nice easy form?”

“Rather!”

“There’s no fagging above the Upper Fourth, let me tell you, even for us.”

“Perhaps not. But there’s more kinds of fagging than one, and I prefer to do mine for pollies in the house, not over lessons.”

The big new boy headed for his own house, and Carpenter wanted to discuss what he had meant. But Jan was not interested, and was not to be led into any discussion against his will. He had a gift of silence remarkable in a boy and irritating in a companion. Yet he broke it again to the extent of asking Heriot at dinner, apropos of nothing, when the other boys would start to arrive.

“The tap will be turned on any minute now. In some houses I expect it’s running already.”

“Which house is Devereux in?” asked Rutter, always direct when he spoke at all.

“Let me think. I know — the Lodge. The house opposite the chapel with the study doors opening into the quad.”

The boys had time for a short walk after the meal, and more than a hint to take one. They only went together because they were thrown together. They seemed to have as little in common as boys could have. Yet there was something else, and neither dreamt what a bond it was to be.

“Do you know Devereux?” Carpenter began before they were out of their quad.

“Why? Do you know him?”

Jan was not unduly taken aback. He was prepared for anything to do with Devereux, including the next question long before it came.

“We were at the same preparatory school, and great pals there,” replied Carpenter wistfully. “I suppose you knew him at home?”

“I used to, but only in a sort of way. I don’t suppose we’ll see anything of each other here. He mayn’t even recognise me, to start with.”

“Or me, for that matter! He’s never written to me since he left, though I wrote to him twice last term, and once in the holidays.”

It was on the tip of Jan’s tongue to defend the absent Evan. But he remembered what he had just said, and held his tongue as he always could. Carpenter, apparently regretting his little show of pique, changed the subject and chattered more freely than ever about the school buildings they passed. There was a house with three tiers of ivy-covered study windows but no quad, there were other houses tucked more out of sight, and Carpenter knew about them all, and which Cambridge cricketing hero had been at this one or at that. His interest in the school was romantic and imaginative, and it contrasted strongly with Jan’s indifference, which grew more perverse as his companion waxed enthusiastic.

A number of boys from Carpenter’s part of the world, it appeared, had already been through the school and had passed on to him a smattering of its lore. The best houses of all, he had heard, were not in the town at all but on the hill a quarter of a mile away. The pair went to inspect, and found regular mansions standing back in their own grounds, their studies and fives courts hidden from the road. Rutter at once expressed a laconic preference for the hill houses, at which Carpenter stood up for the town.

“There’s no end of rivalry between the two,” he explained as they trotted back across the valley, pressed for time. “I wouldn’t be in a hill house for any money, or in any house but ours, if I had my choice of the lot.”

“And I wouldn’t be here at all,” retorted Jan. That took Carpenter’s breath away, or what little breath he still had after hurrying up the hill. But, by following a group of other new boys in the same hurry, they found themselves approaching the chapel and the schoolroom by a shorter route, through a large square quad.

“There’s plenty of time,” said Jan, with a furtive look at the little gold lady’s watch that he pulled out. “I wonder if this is the Lodge?”

“No. It’s the next house, opposite the chapel. This is School House. Do come on!”

School House and the Lodge were like none of the other houses. Instead of standing by themselves, they were part of the cluster of buildings which was dominated by the chapel and schoolroom. In both of them, the study doors opened straight on to the quadrangles, which adjoined each other with no demarcation line between. But in neither was a soul to be seen as Carpenter and Rutter caught up with the last of the new boys at the schoolroom door.

“Let’s go back by the Lodge,” said Jan when at last they were let out for good. By now the scene was changing. Groups of two or three were dotted about in conversation, some still in their journey hats, others in old school caps with faded badges, but none who took the smallest notice of the new boys with the new badges. Rutter horrified his companion by coolly accosting a big fellow just emerged from one of the Lodge studies.

“Canst tha’ tell me if a boy they call Devereux has gotten back yet?” asked Jan, with more of his own idioms than usual.

“I haven’t seen him.” His answer was civil enough, but his stare followed them.

“I shouldn’t talk about ‘a boy’, if I were you,” Carpenter said as nicely as he could, taking Jan’s arm. But Jan was well aware of his other slips, and was already too furious with himself to accept rebuke.

“Oh, isn’t it the fashion? Then I’ll bet you wouldn’t!” he cried, as he shook off the first arm that had ever been thrust through his own by a gentleman’s son.

Back at Heriot’s, a ball like a big white bullet was making staccato music in the fives court, and a great thick-lipped lad of sixteen or seventeen was hanging about the door leading to the studies. He promptly asked the new boys their names.

“What’s your gov’nor?” he added, addressing Carpenter first.

“A merchant.”

“A rag-merchant, I should think! And yours?”

Jan was not embarrassed by the question. He was best prepared at all his most vulnerable points. But his natural bluntness had recently made him so annoyed with himself that he replied as politely as he possibly could, “My father happens to be dead.”

“Oh, he does, does he? Well, if you happen to think it’s funny to talk about ‘happening’ to me, you may jolly soon happen to wish you were dead yourself!”

The tap had indeed been turned on, and the water was indeed rather cold. The more fortunate for Rutter that his skin was thick enough to respond with a glow rather than a shiver.

4. Settling in

Jan was determined not to be impressed. But he was not as indifferent as he pretended, and was still sensitive enough to respond to every new experience. Indeed on one particular matter he was highly sensitive, but that was a matter no longer likely to arise that night. Meanwhile there was quite enough to occupy his mind, and the fact that he was not too easily hurt helped immensely in keeping his wits about him.

There was the long-drawn-out arrival of the boys, one by one, in bowler hats soon changed into school caps, and in loud ties duly discarded for solemn black. Then there was tea in hall, a cheerful occasion with everyone bringing in some delicacy of his own, and newcomers arriving in the middle to be noisily saluted by their friends. Nobody took the slightest notice of Jan, who drifted to a humble place at the long table and fell to work on the plain bread and butter provided, until some fellow pushed a meat pie across to him without a word. The matron dispensed tea from a gigantic urn, and when anyone wanted another cup he simply rattled it in his saucer. Jan could have made even more primitive use of his saucer, for the tea was hot if not strong. But there were some things he did not have to be told, though his counsellor Carpenter had gone out to tea with another boy and his people who knew something about him at home.

Jan was allowed to spend the evening in an empty study which, depending on where he was placed in the school, he might or might not be allowed to take over next day. The bare floor, table, chair and bookshelf, with a cold hot-water pipe and the nails with which the last occupant had studded the walls, looked quite dismal in the light of the solitary candle supplied by Morgan. The passage outside rang with laughter and repartee. Either the captain of the house was not yet back or he was not one to play the martinet this first night of the term, and Jan was left as severely alone as he could have wished. But when someone pounded on his door and shouted that it was time for prayers, he was ready enough to mingle with the crowd in hall.

Everyone was standing at the tables, armed with hymn-books but chatting merrily, and one of the small fry was on the watch in the flagged passage leading to the green baize door. Scarcely had Jan found a place when this sentry flew in with a sepulchral ‘hush!’ In the silence that descended, Miss Heriot entered, followed by her brother, who gave out the hymn which she played on the piano, and which the house sang heartily.

One of the many drawbacks — if drawback it was — of Jan’s strange boyhood was that he had been brought up practically without religion. There had been none in his humble home or in the stable. The vicar who was the first to take an interest in his intellectual welfare had been so eccentric that Jan had picked up nothing spiritual from him. In his new home he had met another kind of clerical example which appealed to him even less. To most English schoolboys prayer, whether heartfelt or pretended, is normal practice. Not so to Jan, and he paid very little attention to the prayers which Heriot read.

After milk and biscuits (which he heard called ‘dog-rocks’) he spent another dreary half-hour in the empty study until it was time to go up to bed. His thoughts were still so far from prayer that he was much impressed by what happened in the little dormitory at the top of the house, when he and his three companions were undressing. Joyce, the captain of the dormitory, who proved to be a rather delicate youth with a most indelicate vocabulary, suddenly demanded silence for ‘bricks.’

“Know what bricks are?” asked Bingley, whose tish was next to Jan’s and who turned out to be a boy of his own age, instead of the formidable figure of his imagination.

“It’s your f****** prayers,” said Joyce. Jan could hardly believe his ears.

“Joyce, you’re a brute!” complained Crabtree, poking a red head round his curtain.

“Nevertheless, my boy” — Joyce was imitating a master through his nose — “I know what bricks are, and I say them.”

“Obvious corruption of prex …” Crabtree was beginning didactically when Joyce cut him short.

“Shut your a***!”

Silence reigned for the best part of a minute. Jan went on his knees with the others, marvelling at the language of the nice fellow in the corner. It was the kind of language he had constantly heard in the stable, but it was the last kind he had expected to hear in a public school. For the first time in his life it shocked him. But he was thankful to find himself in such pleasant company, and for the first time in his life it occurred to him to express his thankfulness, though not to anyone in particular, while he was on his knees.

He had, for a boy, an unusually sound instinct for character and, as they lay talking in the dark, nothing cropped up to modify his first impression of his room-mates, nor did it as the weeks went by. Joyce’s only foible was his fondness for dirty words: it was not what he said but how he said it, and he had a fine sense of humour. Crabtree was impeccable in his language, and a kindly creature in his cooler moods, but he suffered from the curse of intellect — he was precociously didactic and dogmatic — and his temper was as fiery as his hair. Bingley was a gay, irresponsible, curly-headed dog who enjoyed life in an insignificant position both in and out of school. The other two had nicknames which were not for the lips of new boys, but Jan called Bingley ‘Toby’ after the first night.

Presently the talk died down, but the silence was not quite complete. Someone’s bed-springs were rhythmically creaking, very quietly at first, then more audibly and rapidly as caution was thrown to the winds. Jan smiled to himself: so this was another realm where gentlemen’s sons differed not a whit from stable-boys. But tonight he did not feel like following suit.

There was nothing, on the first morning of term, until ten o’clock when the whole school assembled in the big schoolroom to hear the new school order. Jan found himself wedged in a crowd converging at the foot of the worn stone stairs. Yesterday he had trotted freely up and down them. Now he was slowly hoisted in the press, the breath crushed from his body, his toes only occasionally encountering a solid step, a helpless mouse in a monster’s maw. At the top of the stairs, however, and through the studded oak door, there was room for all. A careful but furtive search revealed nobody he knew from former days.

Carpenter, who had squeezed into the next seat, was watching the watcher, and whispered, “He’s not come back yet.”

“Who’s not?”

“Evan Devereux. I asked a fellow in his house.”

“What made you think of him now?”

“Oh, nothing. I only thought you might be looking to see if he was here.”

“Well, perhaps I was,” admitted Jan with grumpy candour. “But I’m sure I don’t care where he is.”

“No more do I, goodness knows!”

Between three and four hundred boys were chattering with subdued animation. The pollies more or less kept order but themselves chatted to each other, as was only natural this first morning. Then suddenly there fell an impressive silence. The oak door opened with a tremendous click of the latch like the cocking of a huge revolver, and in trooped all the masters, cap in hand and gown on shoulders, led by a little old man with a kindly, solemn and imperious air. Jan felt that this could only be Mr Thrale, the Headmaster, but Carpenter whispered, “That’s Jerry!”

“Who?”

“Old Thrale, of course, but everybody calls him Jerry.”

Jan liked everybody’s impudence as Mr Thrale took his place behind a simple desk on the platform and read out the new list, form by form, as impressively as if it were holy writ. The first names that Jan recognised were those of Loder, the captain of Heriot’s, and Cave major, its most distinguished cricketer, in the Upper and Lower Sixth respectively. Joyce was still in the Remove, but Crabtree had moved from the Lower to the Upper Fifth. The next that Jan knew was Shockley — the fellow who had threatened to make him wish he was dead — and then thrillingly, long before he had expected it, Carpenter’s name and his own in quick succession.

“What form will it be?” he whispered into Carpenter’s ear.

“Middle Remove. And we don’t have to fag after all.”

Devereux was the next and the last name that Jan remembered hearing, and in the Upper Fourth, the form below his!

The new boys had already learnt that masters took their classes in hall in their own houses. They now discovered that Mr Haigh, the form master of the Middle Remove, had just succeeded to the most remote of the hill houses. His new form therefore trudged out there, and on the ten minutes’ walk Carpenter and Rutter had their heads knocked together by Shockley, for having the cheek to get so high and to escape fagging their first term.

“But you needn’t think you have,” he added ominously. “If you young swots come flying into forms it takes the rest of us two years to get to by the sweat of our brow, by God you’ll have all the swot you want! You’ll do the construe” — he meant the translation — “for Buggins and me and Eyre major every morning of your miserable lives!”

Buggins (who rejoiced in a real name of less distinction, and a strong London accent) was climbing the hill arm-in-arm with Eyre major (better known as Jane), who was his bosom friend, his echo and his shadow. Buggins embroidered Shockley’s threats, Eyre major contributed a faithful laugh. Jan heard them all unmoved, and thought the less of Carpenter when his thinner skin turned pale.

Mr Haigh gave his new form a genial welcome, and vastly reassured those who knew least about him by laughing uproariously at things too subtle for them to understand. He was a muscular man with a high colour, a very clever head, and a body that bulged as bodies do which are no longer young and energetic. Energy he did have, but spasmodic and intemperate, though on this occasion he only showed it by pouncing savagely on a small boy who happened to be in his house. Up to that moment Carpenter and Rutter had been congratulating themselves on their form master. But, though he left them considerately alone for a day or two, they were never sure of Mr Haigh again.

This morning he merely announced the scheme of the term’s work and gave out a list of the books required. Some of them were enough to strike terror in Jan’s heart, and others made Carpenter look worried. Ancient Greek geography was not an attractive subject to one who had not even set eyes on a modern atlas until the last six months; and to anyone as poorly grounded as Carpenter claimed to be, it was an inhuman jump from Stories in Attic Greek to unadulterated Thucydides.

“I suppose it’s because I did extra well at something else,” said Carpenter innocently on their way down the hill. “What a fool I was not to take that fat chap’s advice! Why, I’ve never even done a page of Xenophon, and I’m not sure I could say the Greek alphabet to save my life!”

“I only hope,” Jan replied, “that they haven’t gone and judged me by that unseen!”

But their work began lightly enough, and that first day the furnishing of his study gave Carpenter food for much anxious thought. Not so Jan. He was genuinely indifferent to his surroundings, and his companion’s enthusiasm made him pretend to be even more indifferent than he felt. He was to keep the upstairs study at the back in which he had spent the previous evening, and Carpenter had the one next to it. After dinner Heriot signed orders for carpet, curtains, candles and candlesticks, a table-cloth and a folding armchair apiece, as well as for stationery and books, and Carpenter led the way to the upholsterer’s. He took an age choosing his curtains, carpet and table-cloth, all of a harmonious shade of red. Jan made all the more point of leaving the choice of his entirely to the shopkeeper.

“Send me what you think,” he said. “It’s all one to me.”

On the way back Carpenter reproached him. “I can’t understand it, Rutter, when you have an absolute voice in everything.”

“I hadn’t a voice in coming here,” replied Jan, so darkly as to close the topic.

“I suppose I go to the other extreme.” Carpenter was characteristically frank. “I shall have more chairs than I’ve room for if I don’t take care. I’ve already bought one from Shockley.”

“Good night! Whatever made you do that?”

“Oh, he dragged me into his study to have a look at it, and there were a whole lot of them there — Buggins, and Jane Eyre, and the one they call Cranky — and they all swore it was cheap as dirt. There are some beasts here!” he added under his breath.

“How much was it?”

“Seven and six. And I didn’t really want it a bit. And one of the legs was broken all the time!”

“And the gang of them are in our form and all!”

They met most of the house trooping out of the quad with bats and pads, on the way to the Middle Ground for a house game. The September day was warm, and there was no more school until five o’clock. The new boys did not need Shockley’s threats to turn round and go with the rest, but their first game of cricket was not a happy one. They found that nobody took it in the least seriously, except a bowler off whom Carpenter missed two catches; they failed to make a run between them; and of course they had no chance of showing whether they could bowl. Both were depressed when it was all over.

“It served me right for dropping those catches,” said Carpenter with the stoicism of a true cricketer.

“I only wish it was last term instead of this!” muttered Jan.

There was another disappointment. The Lodge happened to be playing on the next pitch, but Devereux was not among the players, and they heard somebody say that he was not coming back until half term. Jan’s heart jumped: by half term he would have settled down, by half term many things might have happened. Yet postponing the meeting might make it worse. On the whole he would have been glad to get it over. At one moment this half-term’s grace was a relief, at another it was a sharp disappointment.

5. Nicknames

Public-school nicknames are readily invented and generally apt. Carpenter’s and Rutter’s were not outstanding examples, but at least both were awarded before the boys had been three days in the school, and both were too good an accidental fit to be easily dropped or forgotten. Thus, although almost every Carpenter has at some stage been ‘Chips,’ in this case a rather big head on rather round shoulders, and a tendency to dawdle when not excited, did recall the slowest of workmen. Chips Carpenter, although unduly sensitive in some things, had the wit to accept his nickname as a compliment. In the end it was the same with Rutter. But the way in which he earned it made it a secret bitterness, in spite of the reputation it gave him.

On the Saturday afternoon, directly after dinner, most of the house were hanging about the quad when there entered from the outside world a peculiarly disreputable scoundrel, a local character notorious among the alehouses, whose chief haunt was the Red Lion. The boys in the quad hailed him as ‘Mulberry,’ another highly appropriate nickname, for never did richer complexion or bigger nose adorn the human face. The trespasser, being slightly but quite amusingly drunk, found in the boys an appreciative audience. He was not an ordinary stable sot, and had clearly seen better days. He had ragged tags of Latin on the tip of a treacherous tongue. He now asked tenderly after the binominal theororum, but correctly ascribed a swear-word to a lapsus linguae.

“I say, Mulberry, you are a swell!”

“Full marks for that, Mulberry!”

“My dear young friends, I knew Latin before any of you young devils knew the light.”

“Draw it mild, Mulberry!”

“I wish you’d give us a construe before second school!”

For all his days, Jan remembered the incongruous picture of the debauched intruder in the middle of the sunlit quad, with young and wholesome figures standing aloof from him in good-natured contempt, and more faces at the ivy-mantled study windows. Mulberry’s bloodshot eye flickered over his audience in a comprehensive wink which stopped by chance on Jan, who happened to be nearest to him.

“You bet I wasn’t always a groom,” said Mulberry, “an’ if I had been, there are worse places than the stables, ain’t there, young fellow?”

Jan wished the earth would swallow him, but he was more easily angered than cowed, and the brown flush which swept his face was due not only to embarrassment.

“How should I know?” he cried. His voice had not wholly finished breaking, and in his indignation it rose an octave above its usual level.

“He seems to know more about it than he’ll say,” observed Mulberry, and with another wink he fastened his red eyes upon Jan, who as usual had his cap pulled over his eyes, and arms akimbo in the absence of trouser pockets.

“Just the cut of a jock!” A jockey, he meant, but his weasel mind recalled that ‘jock’ was also a low expression for the private parts. “But only a colt’s jock,” he added.

“You’re an ugly blackguard,” shouted Jan, understanding both allusions, “and I wonder anybody can stand and listen to you!”

At this point Heriot appeared very suddenly upon the scene, seized the intruder by both shoulders, and had him out of the quad in about a second. He rejoined the group, his face pale and his spectacles flashing.

“You’re quite right,” he said to Jan. “I wonder too — at every one of you — at every one!”

He turned on his heel and was gone, leaving them stinging with his scorn. Jan would have given a finger from his hand to be gone as well, but he found himself hemmed in by clenched fists and furious faces, his back to the green palings under the study windows.

“You saw Heriot coming!”

“You said that to suck up to him!”

“Beastly cheek, for a beastly new man!”

“But we saw through it, and so did he!”

“Trust old Heriot! You don’t find that sort of thing pays with him.”

“I never saw him,” said Jan steadily, despite a thumping heart, “so you can say what you like.”

“And why should you lose your wool with poor old Mulberry?” Shockley demanded with a fine show of charity, dealing a heavy blow which Jan took without wincing. “Makes one think there was something in what he said.”

“You fairly stink of the racing stables,” said Buggins. “You know you do, you brute!”

Eyre major led the laugh.

“Racing stables!” echoed Shockley. “There’s more of the stable-boy about him than the jock."

Jan folded his arms and listened stoically.

“Ostler’s lad,” said someone.

“Nineteenth groom,” said someone else.

“The tiger!” piped a smaller boy than Jan, using the current term for a smartly-dressed boy groom. “The tiger that sits behind the dog-cart — see how he folds his arms!” And the imp folded his.

This was more than Jan was going to stand. His common sense knew that submission to superior force was a law of nature, which his self-control allowed him to obey. He would have taken the insult from a bigger boy, but to take it from a smaller boy was too much. His left hand flew out and fell with a resounding smack on the side of an undefended head.

In a moment Jan was pinned against the palings by the bigger fellows, his arm twisted, his person kicked, his own ears soundly boxed and filled with abuse. He fought and kicked back as long as he had a free leg or arm. But through it all the satisfaction of that one resounding smack survived, and kept him just sane enough to stop short of tooth and nail.

“Tiger’s the word,” panted Shockley when they finally overwhelmed him. “But if you try playing the tiger here, ever again, you little bastard, you’ll be killed by inches, as sure as you’re blubbing now! So you’d better creep into your lair, you young tiger, and lie down and die like a mangy dog!”

It had taken some time to produce the tears, and they had dried before Jan gained his study and slammed the door. There he sat in his misery, hot, dishevelled, aching and ashamed, yet rejoicing at the one shrewd smack he had landed on an impudent head. That consoled him all the afternoon. The studies emptied. It was another belated summer’s day, and there was a game worth watching on the Upper. Soon there was no sound to be heard but those from the street, but Jan sat staring at the wall as though the fresh air was nothing to him, as though he had not been brought up in his shirtsleeves in the open in all weathers. He was still sitting and staring when a hesitant step came along the passage, paused in the next study, and then at Jan’s door.

“What do you want?” he demanded rudely when he opened the door to Carpenter’s half-hearted knock.

“Oh, I don’t exactly want anything. I can clear out if you’d rather.”

“All right. I’d rather.”

“Only I thought I’d tell you it’s roll-call on the Upper in half an hour.”

“I’m not going to roll-call.”

“What?”

“B***** roll-call.”

Carpenter winced. He did not like swearing, and he liked Rutter enough to wince when he swore. But still less did he like Rutter’s meaning. He was a law-abiding boy who had been at a good preparatory school, and he could scarcely believe his ears. Rutter certainly looked as if he meant it, with his tight mouth and sullen eyes. But he obviously could not carry out his mad intention.

“My dear man, it’s one of the first rules of the school. You’d get into a frightful row.”

“The bigger the better.”

“You might even get bunked” — Chips was acquiring school terminology as fast as he could — “for cutting roll-call on purpose.”

“Let them bunk me! Do you think I care? I never wanted to come here. I’d as soon’ve gone to prison. It can’t be worse. At any rate they let you alone there — they’ve got to. But here … let them bunk me! It’s the very thing I want. I loathe this hole and everything about it. I don’t care if you say it’s one of the best schools going, or what you say!”

“I say it’s the best. I wouldn’t swap it for any other — or let a little bullying put me against it. And I have been bullied, if you want to know.”

“Perhaps you’re proud of that?”

“I hate it. I hate lots of things more than you think. You’re in that little dormitory. You’re well off. But I didn’t come here expecting to find it all skittles. And I wouldn’t be anywhere else if it was twenty times worse than it is!”