Indelicate Frivolities

4. The Tarses of Sodom

Rob inspected Hugo’s monumental member without much enthusiasm. “Nice size,” he admitted. “But I don’t call it an erection till it’s at least horizontal. Preferably higher.”

Hugo looked down at himself. “Oh dear,” he sighed. “I did hope it would be stiffer than that.”

“Well …” Rob tried to be more positive. “I might be able to help. Mind if I feel you up?”

The subject of this conversation wasn’t quite what you think. To find out what it really was, you’ll have to read on. But if you do, blushful reader, you’ll be exposed to what has been called, with good reason, the filthiest play ever written. It may be no more to your taste than it is to mine. Be warned.

*

Hambledon’s repeat production — ‘Gammer on tour’, we called it — proved a resounding success. Prufrock kept in touch by email, and in the Easter holidays the four of us went up to Cambridge for the day to spy out the land. All our expenses were being paid, and we went by train. Hugo, who as usual was staying at Bumley, travelled up with Alex, and Rob and I joined them at King’s Cross.

Most of the journey we spent talking about Christ’s College. Rob and I, having been there briefly for our interviews in November, were regarded as experts. It was right in the centre of the town, we explained. Like almost all Cambridge colleges it was co-ed, with nearly 400 undergraduates and almost 100 graduates. It had been founded in 1437 as God’s House, but re-founded in 1505 as Christ’s.

“Who went there,” asked Alex, “who’s famous? Apart from William Stevenson, of course.”

“John Milton,” I replied at once, before Rob could step in. “There’s a mulberry tree he used to sit under. So they say. Planted in 1608. It still bears fruit.”

“Charles Darwin,” said Rob, unimpressed. “He went up in 1828. They’ve refurnished his room as it was in his day.”

“The Archbish of Canterbury,” I added, “Rowan Williams.”

“Umm … Sacha Baron Cohen,” Rob offered. Then, after a pause, “Tony Lewis.”

“Who’s he?”

“Cricketer. Captained England.”

“Oh … Do you think that girl knows we can see her?”

The train had mysteriously stopped between stations, as trains do, and we were abreast of the first floor of an anonymous terrace house. A young lady, totally naked, was standing lasciviously at the window.

“I’m sure she does.”

“How silly!” said Alex austerely. The train moved on.

We took a taxi to Christ’s, where Prufrock greeted us warmly, his leers as lecherous as ever. “Some changes of plan, I fear,” he boomed. “Irritating, highly irritating, but ineluctable. I failed to persuade the Governing Body to allow you to stage Gammer in Hall. It feared you would hammer nails into the panelling. As if the panelling were the original which Stevenson knew! That was torn out in 1876 by George Gilbert Scott, a pox upon his head. Barbaric, quite barbaric. But no matter, no matter. For that reason the play would not have been authentic in Hall. Indeed there is nowhere that is wholly authentic. Instead, you will be performing in the theatre which, by contrast, is wholly modern. It wants no item of equipment.”

The college theatre, it turned out, was the base of the Christ’s Amateur Dramatic Society, or CADS for short. But, because it was the middle of vacation, no undergraduates were around and Prufrock himself acted as our guide. It was indeed well-appointed, but the stage was rather small. Rob, having prowled with a tape measure, announced that our set would fit in, just. But because the stage was shallow from front to back, the street would be narrow. “The house-front will have to be here,” he said, pointing with his toe.

“Not enough room for the hens, then,” Hugo observed. “But still room for Piglet.”

“No Piglet,” said Alex.

“No Piglet! Why not?”

“Haven’t you noticed?” Alex asked callously. “For the last week we’ve been having him for breakfast.” He giggled at Hugo’s horrified face. “There are some new piglets, but it’d be a pain to transport one all this way, and how could we train him? No animals this time.”

Myself, I wasn’t too disappointed. And Alex was evidently leaving childish things behind.

We talked about other preparations. Christ’s had already commissioned its own replicas of the inglecock and William’s portrait and high-quality facsimiles of the manuscript. For the advance education of the audience — which had proved so important at Hambledon — these would be displayed in the foyer for all to see. Then we would need not only a large van to cart our set and props and costumes and instruments from Hambledon, but also the services of a CADS technician who knew the ropes here. Prufrock, having promised to organise both, disappeared. We checked that the drops were what we wanted. We did a brief dummy run to test the acoustics. Rob tinkered with the lighting console. Everything, in short, seemed to be in order.

Satisfied, we stood on the stage. Thinking we were alone, Rob and I had a little hug and kiss. So did Hugo and Alex. Somebody clapped. Without us noticing, Prufrock had re-materialised in the back row. Oops. But no great surprise, and no harm done. He was now not only leering but beaming, as if he had been proved right.

*

The team’s visit to Cambridge in June deserves chronicling at greater length; not so much because of the production of Gammer, but because what transpired then was destined to affect our future. At Hambledon we loaded the scenery and our clobber into the van which Prufrock had sent down. We loaded ourselves into two of the school’s minibuses and drove to Christ’s. University term had just ended and some undergraduates had already left, but most were still in residence. Again we were welcomed, not only by Prufrock who was bouncing with excitement like a small boy at his birthday party, but by all the members of CADS. We picked up our bags and our hosts showed us our rooms, vacated by those who had already gone down. Prufrock took personal charge of Rob and me.

From the porters’ lodge he led us, twittering as he went, through First Court, along the passage beneath Hall, and into Second Court. Ahead lay the stately Fellows’ Building, erected in the 1640s as one of the earliest examples of neo-classical architecture in Cambridge. He headed for the right-hand entrance. We were astonished that we were being housed in such elegant quarters. Up a flight of stairs, and he flung open a door labelled B4 and waved us in. The room was huge, the full width of the building, with windows at each end. One looked over Second Court towards the back of Hall, the other over the Fellows’ Garden with Milton’s mulberry tree at the far end. It was oak-panelled throughout and sported two large seventeenth-century portraits. It was furnished, if not in period style, in good taste, and from it led two further doors. One opened into an en-suite shower and loo, blatantly not original. The other led to a sizeable bedroom in which was a double bed.

We were flabbergasted. And when Prufrock dropped his bombshell we were more flabbergasted still.

“When you join us in the autumn,” he said, “these will be your rooms for the next three years. For longer, perchance, should you stay on.”

“But,” I protested, “we couldn’t possibly afford it.”

Here I must explain about accommodation. At Christ’s — unusually for Cambridge — you got a room in college for all your time, rather than having to go into digs for your second year. But rooms, as we knew from the prospectus, varied hugely in size and desirability, from little more than glorified broom-cupboards to the palatial. The rent you paid varied accordingly. Freshers were randomly allocated bog-standard ones, mostly in the concrete modernity in New Court which was understandably known as the Typewriter. In your second and third years you could apply for the price-range or even the particular room you wanted, and the allocation was by ballot. The system sounded pretty fair.

On top of that, almost all rooms were single. The very few double rooms were pricey and were never, we thought, given to freshers. Rob and I, having shared our Hambledon room for five years, were resigned to being apart. There’d be nothing against us visiting each other, even by night, but it wasn’t the same thing. For our second and third years, being impecunious, we expected nothing much better. But this! … Breathtaking though the prospect was, there was an obvious snag. It must be about the most expensive room in college.

So I protested, “But we couldn’t possibly afford it.”

“You will be charged,” Prufrock said firmly and, for him, simply, “on the lowest rent-band.”

“But why? How?”

“Them that asks no questions isn’t told a lie.” It was strange to hear Kipling from the lips of so renaissance a man. “Almost the first occupants of this room,” he added quickly as if to forestall further questions, “were John Finch and Thomas Baines, both later knighted.” He waved at the two portraits. “Remember the names. Finch and Baines. Their history will repay your study. Ask the Librarian about them. And visit Chapel. But not now, not now. More urgent matters await. Deposit your baggages, and follow me.”

All we could do was exchange a bewildered look, deposit our baggages, and follow him. He took us to the car park where the others were beginning to unload the van. We joined in and, with much help from CADS, got everything into the theatre. Once the set was installed and the sliding house-front was sliding to our satisfaction, it was time to return to our rooms to wash and change into something more respectable; for we had a date. We reassembled in the SCR — the Senior Combination Room — where we were greeted by the Master himself. Charlotte was also there, having driven herself up from Bumley to stay in the Master’s Lodge.

The Master welcomed us with sherry and a gracious little speech. He singled out Alex as the first Stevenson to set foot in Christ’s, as far as was known, since William left in 1561. “And I almost feel,” he added with a puzzled glance around, “as if William Stevenson himself were with us.”

How right he was. William was with us. Once again he had hitched a lift in the Volvo. And as well as Alex, the Master singled out Hugo Spencer, Rob Nethercleft and Sam Furbelow as the co-discoverers and re-creators of the real Gammer.

“If Hambledon is in your debt,” he said, “so too is Christ’s. Stevenson is ours as well as yours. We honour our sons as you honour your father.” He thereupon added a special welcome to Rob and me as imminent members of the college, and to Hugo and Alex as, he hoped, future ones. What a civilised place this was!

Hugo, who as producer was nominally in charge of our gang, replied with another gracious little speech. With his background, he was good at that sort of thing. Then we trooped into Hall for dinner. They gave us the works. We sat at High Table, along with the current president and secretary of CADS, a few literary Fellows, and the Librarian. The table sparkled with silverware and candles. The meal far outdid our ordinary fare at Hambledon. “Mind you, it isn’t always like this,” I heard the secretary of CADS mutter to her neighbour. Then back to the SCR for coffee and port. By the time that was over it was late, we were weary, and a busy day beckoned tomorrow.

“Where’ve they put you up?” I asked Hugo and Alex as we emerged into Second Court.

“Over there.” Hugo pointed to the right. “Staircase E. Pretty good. And a double room. OK, twin beds, but still a double room. Dunno how they knew.”

“I can guess,” said Rob. “It’s Prufrock. He saw you snogging at Easter, remember? It’s the same with us. But we’ve got a double bed. And it’s ours for three years. Come and see.”

We took them to B4. “Blimey!” Alex exclaimed. “It’s ginormous! But won’t it cost a fortune?” He knew we weren’t exactly rolling.

“No. Lowest rate-band. For some reason.” But I was beginning to suspect why.

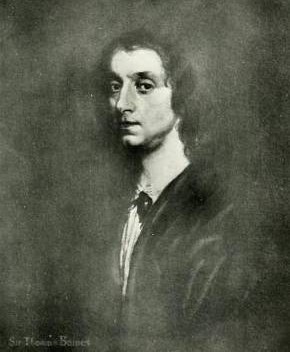

“And who are these guys?” Alex was looking at the portraits. “Oh, it says. Sir John Finch and Sir Thomas Baines. What did they do?”

“No idea. Got to find out tomorrow, if there’s time. But Prufrock said they were almost the first people to live in these rooms. 1640s, that must have been.”

“Baines isn’t very cheerful, though. Disapproving, almost. Was he a Puritan?”

“Could be.” Alex was right. Baines was a far cry from the portrait of sweet young William. “Still, I expect we’ll get used to them.”

Hugo and Alex retired to their twin beds and we to our double. Next morning it was up early, a quick self-service breakfast, and into rehearsal. First we ran through the appropriate parts of Gammer to make sure the technology worked, and then did a full dress rehearsal. No serious problems at all, and we unexpectedly found ourselves free for the afternoon. Rob called on Dr Mulligatawny, his future director of studies, for a chat about his first-year course.

But I was summoned by the library. Last night the Librarian had plied me with learned questions over port in the SCR — God, it seemed grand to talk in those terms! She had, she said, a further query about the watermarks in William’s manuscript. Should I have a moment, she would be honoured if could I drop round. God, it was good to be here, no longer a solitary geek but a scholar among scholars!

I dropped round. The Librarian was grey-haired, staid of appearance, and delightful. We had our technical chat, and she showed me some of the treasures in her charge. Then I remembered Prufrock’s command and asked her about Finch and Baines, adding that their rooms were now ours.

“Are they indeed?” was her reply. “Interesting. In that case you’d better borrow this.” She went to a shelf and pulled out a book. “You aren’t quite a member of college yet, but rules are there to be broken. And you haven’t a card yet, so I’ll sign it out in my name. Bring it back next term.” No silly instructions about taking care of it. Just scholarly trust. God, what a place!

The title page read ‘Finch and Baines, a seventeenth century friendship, by Archibald Malloch, Cambridge 1917.’ I flipped a few pages and was confronted by a photo of our room. It suddenly became important to delve deeper. I thanked her profusely and fled with Malloch to B4.

The book wasn’t long, only eighty-odd pages. As I surfaced an hour later, Rob came back from Mulligatawny, and I filled him in. John Finch, it appeared, was a man of standing. His father was Speaker of the House of Commons and his elder brother later became Earl of Nottingham. He went first to Balliol, but when Oxford got nastily snarled up in the Civil War he moved to Cambridge. “This’ll interest you,” I said. “He was related to William Harvey.”

“Oh, right! The bloke who discovered the circulation of the blood.”

Thomas Baines was a few years older, and a man of the people. He was already at Christ’s when Finch arrived, and for six years they shared our room. I showed Rob the photo. Edwardian furniture apart, it was exactly as now. Having taken their MAs together in 1649, the year Charles I lost his head, they left for Italy. Together they went to Padua University where they qualified as doctors. Then Finch was appointed professor of anatomy at Pisa University, and Baines stayed with him. Their reputation as medical men blossomed.

In 1661 they returned to England where Finch was knighted. Together they became Fellows of the Royal College of Physicians, Doctors of Physics at Cambridge, and Fellows of the Royal Society. But Finch was more than a doctor. He became a diplomat. He was sent back to Italy as ambassador to the Grand Duke of Tuscany at Florence, and Baines went with him. After another brief spell in England when Baines too was knighted, Finch was made ambassador to the Turkish sultan in Constantinople, where Baines served as his secretary and as physician to the embassy.

But Baines had long suffered from gout and from appalling kidney stones, and in 1681 he died. Finch was inconsolable. He buried Baines’s innards under a memorial which referred to their ‘wonderful, devoted friendship’ and their ‘beautiful and unbroken marriage of souls and inseparable companionship of thirty-six whole years.’ The rest of his body he embalmed, brought back to England, and buried here at Christ’s. Next year Finch too died and was buried beside him. He left the college £4,000, which was then one hell of a lot of money.

“That’s extraordinary,” said Rob. “Do you think they were actually …?”

“The sources don’t say. You’d hardly expect them to, not in those days. This book implies they were just damn good friends. David and Jonathan, sort of. OK, some people like to see David and Jonathan as sexual partners, though the evidence is vanishingly thin. But these guys here met up when they were, um, nineteen and twenty-three, and they stayed together till they died. They were literally never parted. It does make one wonder. But I doubt we’ll ever know for sure.”

“‘Marriage of souls’,” Rob quoted thoughtfully. “They can’t have been married literally.”

“Oh no. That must be metaphorical. But they must’ve been liberal types. They spent the Commonwealth out of the country and came back at the Restoration. That’s too much of a coincidence. They can’t have been Puritans.”

“Was Christ’s Puritan?”

“Not by their time. Not for a good twenty years. Take Milton, who came up in 1625. He was as Puritan as any, and didn’t fit in.” I laughed. “He saw a comedy put on by the undergraduates in Hall — it could even have been a revival of Gammer, come to think of it — and his verdict was, ‘they thought themselves gallant men, and I thought them fools.’ And they called him the Lady of Christ’s, because he looked girlish and wore his hair long.”

We glanced briefly out of the window at Milton’s mulberry tree, but returned to gaze long at the portraits. Both of them were youngish. But, now that you knew about it, couldn’t you already see suffering written in Baines’s face?

“Are they why Prufrock had us put in here?” asked Rob, marvelling.

To that there was no answer.

“Time we started for the theatre,” I said, looking at my watch. “But let’s drop in to Chapel on the way.”

Finch and Baines were easy to find: a large white marble memorial on the wall between the organ and the altar. There were two portraits in relief — recognisably the same faces as in B4 — draped in garlands which were tied together in a marriage knot. On the plinths below was an inscription in Latin which I translated for Rob. It is really too long to inflict the whole of it on the impatient reader. But it started off by commemorating ‘two dearest friends, whose heart was one and whose soul was one.’ It ended ‘so that they who in life had united their interests, fortunes, deliberations, and indeed their souls, might likewise in death at last unite their ashes.’ Rob found my hand and squeezed it.

The show went well. The house was full. The audience — which included William and, so Prufrock told us, many literary dons from other colleges — reacted exactly as it should. Livestock apart, the only difference from the Hambledon production was the curtain call. After taking our bows we moved to either side of the stage, and onto a plain drop were projected side-by-side photos of the portrait and the first page of the manuscript. The applause redoubled, and I swear that William not only smiled but nodded modestly in acknowledgment.

As we were unwinding, Prufrock came backstage demanding Alex. I thought he was after another inspection of his scantily-clad body, which may indeed have been the case. But he also had an interesting suggestion. He first established that Hugo was still hoping to come to Christ’s the year after Rob and me, that Alex was hoping to come the year after that, and that Alex was taking his A-levels the coming summer.

“Why then,” he asked him, “do you not apply at the same time as Mr Spencer? Should you both be successful, you will come up together. You will not be separated for twelve months as you otherwise would. What age will you have attained in October of next year?”

“Seventeen and a half. But isn’t that too young?”

“No impediment, no impediment at all, provided the candidate is of sufficient quality and promise. Think on it, think on it. But now I am commanded to surrender you all to our thespians. It has been a magnificent and historic occasion which will long be remembered. The college is your debtor. I shall see you tomorrow.” And off he stumped.

“God, if that works!” said Alex, turning excitedly to Hugo, who was equally chuffed. He paused, his head on one side, perhaps communing with William. “Yes! I’ll go for it!”

The senior members having entertained us last night, it was now the turn of the CADS. In high delight at our performance, they bore us away to the college bar and plied us with alcohol, despite the fact that several of us were under-age and Matt, whose voice had still not broken, was seriously so. I found myself next to the secretary, a sweetie called Emma Gotobed, who was brimming with questions about Gammer. When they had been satisfactorily dealt with, she swept an eye over her guests. It rested speculatively on Hugo and Alex.

“Hodge and Cock,” she said quietly to me. “They’re gay, aren’t they? Boyfriends?”

“That’s right.” I decided to test her powers of observation further. “Any other boyfriends visible in our lot?”

She looked round again. “Can’t see any.”

I chuckled. “You’re sitting right next to one.”

“Oh.” She sounded disappointed. “You and …?”

“Rob, over there.” This was a good opportunity to probe for information. “You probably heard the Master say we’re coming up next year.”

“Oh, that was you, was it? I hadn’t got your names in my head then. Great! But you’ll be in separate rooms, won’t you?”

“No, thank God. We’ll be in B4.”

“The Finch and Baines room! You must be well-off!”

“No way. Paupers, almost. But Prufrock says we can have it at the lowest rate.”

“Really? Yes, he’s done that before, so I’ve heard. He must like you!”

“What do you mean?”

“He’s subsidising you. Paying the difference. Out of his own pocket.”

It was as I suspected, and I wasn’t sure I liked it. For two reasons. “Is there a price attached?”

Emma looked at me, working it out. “Oh, I see. No, no price. Prufrock’s as gay as a coot, but I’d be pretty sure he’s never had it off with anyone. He may be a voyeur, but he isn’t a predator. He’s just a lonely old man who likes to be kind. Specially to people he identifies with.”

That was a relief. I really did not want to climb into Prufrock’s bed. “How can we thank him?”

“Not to his face. Definitely not. He wouldn’t like it. Just be kind to him. Just humour him. Chances are he’ll ask you round for sherry, quite often. If you can, go. Don’t look for excuses. He’ll enjoy it, even if you don’t. That’s your best way of repaying him.”

“Right. Thanks for the tip. But there’s something else bugging me. If we’re in B4 on the cheap, aren’t we doing somebody out of it who really wants to be there? Who could pay?”

“Probably not. That room’s so expensive there are often no takers. It’s been empty all this year. So don’t worry about that.”

That was another relief. But it was getting late, and Matt was already a little over-merry. I caught Hugo’s eye, he gracefully thanked our hosts and gathered his flock, and we went to bed. Next morning we unbuttoned the stage, reloaded our clobber, bade a fond farewell to Prufrock, CADS and Christ’s, and drove back to school. And there, in the final days of our term, we bade a fond farewell to each other and to Hambledon.

I spent the holidays in my usual solitude. Alex and Hugo had gadded off with Hugo’s parents to somewhere exotic. I saw Rob occasionally and briefly. But to recharge the coffers I had to get a job, and was mainly to be found stacking shelves at Sainsbury’s. In my limited spare time I gave a polish to my critical edition of Gammer and counted down the days to the beginning of term.

*

Rob and I paused at the entrance to our staircase. Painted on the stonework outside the door jamb was a black panel. On it, below a large white B, was a list of numbers and names. Halfway down came ‘4: S. Furbelow’ and, underneath it, ‘R. Nethercleft.’

“Huh!” said Rob. “Condemned for ever to be bottom boy, am I?”

“Bollocks! I’m bottom boy just as often. Come upstairs and I’ll show you.”

I showed him. And the other way round. We had been abstemious too long.

Thus began our university career. B4 was lovely, and we grew in sympathy with Finch and Baines. All the other occupants of the staircase being dons — the generic term for Fellows — who did not live in, it was wonderfully quiet internally, if externally the bus station was rather too close. College life and lectures rapidly became routine. We made friends and made them fast. One of the first things we learnt was that Cambridge must be one of the most gay-friendly places on earth. If Hambledon had been good, Cambridge was even better.

An even earlier thing we learnt — as we had suspected in June — was that Cambridge is far from the snooty place it is often made out to be. While there was a small clique of Hooray Henrys, everyone else ignored them. Otherwise it was a friendly mix of all sorts, and your background mattered not a hoot. Take Emma, now president of CADS. Her upbringing, as her broad vowels proclaimed, had been anything but posh, yet she was about the most popular person in college.

We had barely been at Christ’s for a day when she appeared in B4 and press-ganged us — far from unwillingly — into joining CADS. She begged us to take part in the freshers’ play, an annual show written and staged solely by freshers. That lay months ahead. But the first CADS play of the academic year, traditionally a Shakespeare or something old, was booked for late November. This year it was to be Julius Caesar, and Emma roped me in as Brutus. Easy enough, as I’d been Brutus once at Hambledon.

This was the time when the new government was making itself thoroughly unpopular with proposals for cuts across the financial board. Worst hit of all were the universities. Subsidies were to be slashed, and the only way to recoup the loss would be by tripling student fees. Although this was not due to take effect for two years, resentment was deep and widespread.

But we had barely been at Christ’s for a week when there was a much more cheering event. On the way back for lunch from a lecture, I bumped into Rob in the porters’ lodge. Both of us were heading for our pigeon holes to see if we had any post. There were no letters, but we both had notes to say that we had parcels to collect.

“In the corner there,” said the porter. “They weigh a ton!” There were two huge boxes, and yes, both were addressed to both of us.

“What on earth are they?” we asked each other simultaneously.

“Booze, gents, booze,” said the porter. “I know booze when I see it.”

But who the hell from? We picked up a box apiece and staggered off, the porter gazing wistfully after us. Safe in B4 we tore them open. He was right. A dozen bottles of single malt in each box. One was all Islays — Laphraoig, Lagavulin, Bruichladdich, Lochindaal — the other all Highlands — Balvenie, Glenmorangie, Brora, Highland Park.

“Jesus!” cried Rob, calculating. “There’s the best part of a grand’s worth here! Who …?”

“Look, there’s an envelope.”

He ripped it open. Inside was a sheet of stiff notepaper with a handwritten message.

Dear Sam and Rob,

We wanted to thank you for all you’ve done for Hugo, and especially for helping him out of the clutches of the Villiers boy. Since then he’s been the happy soul he was before.

He tells us you’re both partial to this. We felt it might not be tactful to send it to you at school, or even at home, so it’s had to wait until you arrived at Cambridge. Enjoy!

Warm regards,

Everard and Hermione.

At the top was the printed heading ‘Pidley Hall, Warwickshire.’ The Spencers! Hugo’s parents! We’d never even met them. We looked at each other in blank amazement.

Having sent a heartfelt thank-you letter, we debated how best to enjoy and conserve our stocks. We decided never to drink any until after dinner, and only sparingly at that. We wanted to become neither prematurely alcoholic nor prematurely maltless. But we always kept two bottles on the go. Where I am a Highland fan, Rob prefers Islay, which is far too peaty for my palate.

“How you stomach it is beyond me,” I complained. “It tastes of TCP.”

“How do you know? TCP should never be swallowed. It says so on the bottle.”

“Smells of TCP, then.”

(In case you know it not, TCP is a mild antiseptic named after its original composition of trichlorophenylmethyliodosalicyl, now replaced by a mixture of phenol and halogenated phenols. For this note I am indebted to my scientific adviser.)

*

Emma proved right. Prufrock did ask us round for sherry of an evening, usually once a week. As advised, we went. It proved no hardship. As we got to know each other, he thawed, his language became less outlandish, he could be great fun, and he displayed no visible signs of the predator. He soon called us Rob and Sam, though we never found it in us to call him Lancelot in return. We would talk about almost any subject under the sun, for (apart from sport, modern music, films and women) he was remarkably well-informed. Rob’s diagnosis was that his loud and eccentric mannerisms were a shell protecting a vulnerable interior.

In due course Hugo and Alex came to Cambridge for their interviews, metaphorically if not literally hand in hand, and we made them as welcome as we could in the short time available.

Julius Caesar also came and went. Not a brilliant production — too stolid and bland for my taste — but CADS seemed pleased enough. Next evening Emma dropped in to B4 with two requests. First, would I stand for election as secretary next year? A compliment, and welcome. Secondly, would I produce the play a year from now? Shakespeare or something, of my choice, subject to the committee’s approval. An even bigger compliment, and I had little hesitation in saying yes. Rob would of course help. He said so.

*

At the end of November, when we were well established in our routine, there befell the curious and crucial episode of the Button Hole, as we came to call it.

What a day that was! One night I sat up very late, writing an essay for Prufrock which had to be in next day. It did not go as well as I hoped, and it took a long time before I could do no more. No problem — I’m an owl who operates better late than early. Rob grumbled that it would deprive him of my presence in bed, but being long familiar with my quirks he didn’t grumble much. So it was far into the small hours before I snuggled in beside him, and disgustingly late that I got up. Luckily I had no lectures that day. What woke me was the arrival of our bedder.

Bedders are a feature of the Cambridge landscape. They are ladies of usually plain appearance and indeterminate age, whose profession is no longer, as it once was, to make beds, but rather to keep undergraduates’ rooms in a cleaner condition than is natural to the species. They attend twice a week at a reasonably civilised hour. We had not persuaded ours to call us anything less formal than Mr Nethercleft and Mr Furbelow, and so perforce we called her Mrs Button; not that we had ever heard her first name. And Button was a bad misnomer. Buttons, as I understand it, are quite small things, but she, while short, was indisputably wide. Still, we got on with her very well, and her labours helped us keep our rooms in not too untidy a state.

I was roused that morning by her trundling her vacuum cleaner into the sitting room. Groaning forlornly, I rolled naked out of bed and straightened the duvet. A towel decently around my waist, I staggered into the sitting room, bade her as civil a good morning as I could muster, and disappeared into the bathroom. She was not one whit surprised, for such behaviour is typical of our kind. Sitting on the loo and standing under the shower, I slowly woke up. I heard her hoovering. That finished, I expected her to be dusting. Instead I heard strange soft knockings which I couldn’t identify. By now I was shaving. Intrigued, I put the towel back round my waist and poked my head out. She had one of those long-handled dusting brushes — I believe the technical term is a cornice brush — and was attacking the upper reaches of the panelling.

“Haven’t done this for years, Mr Furbelow,” she panted. “High time.”

Seeing the cloud of dust raining down, I could only agree. But the sight not being wildly exciting, I returned to my shaver. Just as I finished there was a clatter and an ‘Eeek!’ — the sort of sound uttered by timorous ladies when confronted by a spider or a mouse. But our Mrs B, I knew, was far from timorous. She took spiders in her stride and had once, before our admiring gaze, cornered an intrusive mouse, picked it up by its tail, and flung it out of the window into the Fellows’ Garden. This ‘Eeek!’ might have been elicited by a tarantula or a scorpion, but both seemed unlikely in the temperate climate of B4. So again I poked my head out, and saw the cause of both the clatter and the cry. Her ministrations had dislodged a recessed oblong panel high up below the cornice.

“Oh, don’t tell her, Mr Furbelow!” she pleaded. “If you loves me, don’t tell her!”

It took some questioning before I understood. It turned out that Mrs B’s phobia, far from being of vermin, was of the domestic bursar who was, to use the modern term, her line manager. Mrs B was terrified of being reported for breaking up the happy home.

“Don’t worry, Mrs Button,” I said. “I won’t breathe a word to her, or even the maintenance man. I’ll put it back myself.”

I picked up the fallen panel, brought over a chair, climbed onto it, and stretched. The empty oblong was just beyond my reach. And, as I stretched, I felt my towel slipping. It was a choice between panel and towel. I dropped the panel, clutched the towel, and half-fell, most inelegantly, off the chair.

“Oooo, Mr Furbelow!” Mrs B cackled, “I almost seen what I didn’t ought!” She sounded disappointed about the ‘almost,’ but it was a comfort that she hadn’t quite. I had no desire to challenge Mr Button.

“I’ll find some stepladders,” I said, trying to retrieve a shred of dignity, “and deal with it later. Why don’t you leave this and do the shower?”

Relieved, she did, while I went to the bedroom and dressed. Then she did the bedroom while I sat impatiently, trying not to stare at the empty oblong in the panelling. It was perhaps two inches deep to the dirty plaster behind. And inside it, as I had seen from my vantage point on the chair but she with her small stature could not have seen from the floor, was a book. A small book bound in brown leather. Quite possibly a seventeenth-century book. And in the seventeenth century what sort of book needed to be hidden? Religious deviationism perhaps, or political treason, or … My skin crawled with premonition.

When Mrs B finally took herself off I decided, with a huge effort of will, to get one necessary chore out of the way. I went to the porters’ lodge to drop my essay into Prufrock’s pigeon-hole. On my way back I found Rob returning from his morning’s lectures. I dragged him into B4, shut the door, and put him in the picture. He was both amused and intrigued.

“Shouldn’t leave you alone with winsome ladies, should I? … Yes,” he remarked from the far side of the room. “I can see it from here. Looks interesting. There’s a little ladder in the theatre. I’ll get it.”

Within five minutes he was back. He put the ladder in place. “Your baby,” he said generously. “Up you go.”

Up I went. I took the book out, came down clutching it, subsided into the nearest chair, and lifted the cover. Just as well I hadn’t looked when aloft, for I would most certainly have fallen down.

It opened at the title page. “Does look interesting,” Rob remarked over my shoulder. But I was beyond speech.

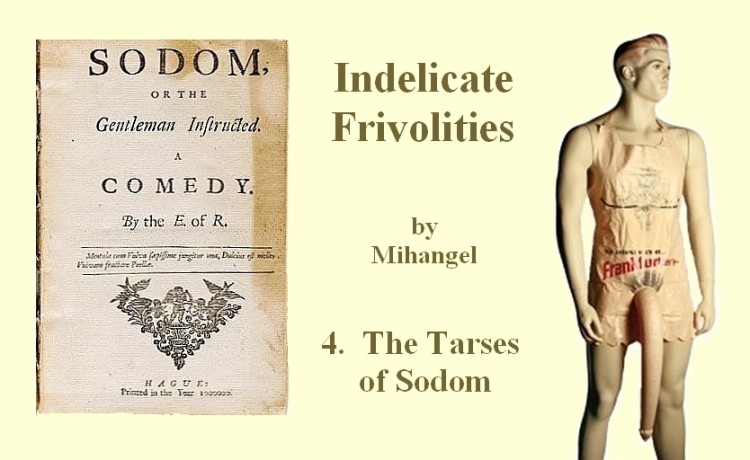

‘SODOM,’ it read, ‘or the Gentleman Instructed. A Comedy. By the E. of R. Mentula cum Vulva saepissime jungitur una, Dulcius est melle Vulvam fractare Puellae. Hague: Printed in the Year 1000000.’

“What does the Latin say?” asked Rob. A very reasonable question, given that he is a scientist, and it jolted me out of my stupefaction. But I still had only a feeble grasp on the world.

“Rob … Balvenie … please.”

He gave me a sharp look. It was long before our agreed starting-time. But he recognised an emergency when he saw one, and brought me a dose of malt which restored me to the land of the living. I returned to the title page.

“When,” I translated, “a prick and a cunt are frequently united, it is sweeter than honey to, um, manipulate a girl’s cunt … But there’s no such word as fractare. It ought to be tractare. Shoddy proof-reading, to have a misprint on the title page.”

“Oh Sam, I do love you!” Rob kissed the top of my head. “In your sticky little paws you’ve got a bit of super-delectable antique porn, and all you can think about is Latin misprints!”

I was bewildered. It was always good, of course, to hear Rob say he loved me. But in scholarship it is niceties that matter. Without them, the world would collapse into chaos.

“Do you know who the E of R was?” he asked.

“Yes,” I said flatly. “Oh yes. John Wilmot, Earl of Rochester. Same sort of time as Finch and Baines, but maybe twenty years younger. A rake. Quite a lad. Wild as they come. Celeb status, like a pop star today. In and out of Charles II’s court. Literally, men and women alike. Died in 1680, a year before Baines. Of syphilis. At thirty-three. Wrote some extraordinary poetry …”

“Such as?”

I dredged my memory. On the spur of the moment the best I could bring up was a verse from ‘The Maim’d Debauchee.’

Nor shall our love-fits, Cloris, be forgot,

When each the well-looked link-boy strove to enjoy,

And the best kiss was the deciding lot:

Whether the boy fucked you, or I the boy.

Rob laughed hugely. “What’s a link-boy? A rent-boy?”

“No. A boy with a torch, to light you on your way home. But he might well be up for sale too.”

“And did you learn that at school?”

“Oh yes. Not straight from Old Persimmon, mind you, though we did talk about Rochester in class. But he encouraged us to look things up for ourselves.”

“Dirty old man. Like Prufrock. Like you. I reckon I’m reading the wrong subject.”

“You are.” Rob was a damn good scientist but, given the chance, he’d have made a damn good literary critic. Underneath his happy-go-lucky veneer his mind was sharp as a razor.

“And what about that silly date? Printed at The Hague in the year one million?”

“A cover-up. There’s no publisher’s name as there should’ve been by law. I bet it was really printed in London. Anyone caught publishing this … well, it would be bloody expensive.” Memories filtered back. I’d read Sodom online, two or three years before, in a French edition published clandestinely a century ago. “It’s a satire, you see. On Charles II, who was an alpha-male lecher, and on his lecherous court. It’s ultra-libellous. If Charles had seen it, Rochester would’ve been for it. And so would anyone printing it. You know why I needed that Balvenie? I wouldn’t be surprised if this is the only original printed copy in existence.”

Rob was still leaning over the back of my chair, and he gasped in my ear.

But my thoughts wandered off on a different tack. The film The Libertine. About all this stuff. Johnny Depp as Rochester, John Malkovich as Charles. It had had an adult-only rating and was screened in few cinemas, and far too long ago for me even to pretend I was eighteen. Rob wouldn’t have seen it either. I’d look for a DVD on the web.

Rob tapped me on the head. “Are you going to let me see inside the bloody thing? I’m itching.”

So I turned the page.

PROLOGUE, it said (though here I modernise the spelling and punctuation).

By Heaven! A noble audience here to day!

Well, Sirs, you’re come to see this bawdy play,

And faith, it is debauchery complete,

The very name of it made you mad to see it;

I hope it will please you well. By Jove, I think

You all love bawdy things as whores love chink.

“Chink?” asked Rob.

“Money. From the sound it makes.”

I do presume there are no women here —

’Tis too debauched for their fair sex, I fear,

And sure they’ll not in petticoats appear.

And yet, I am informed, here’s many a lass

Come for to ease the itching of her arse —

Before three acts are done of this our farce

They’ll scrape acquaintance with the standing tarse …

“Tarse?”

“Prick.”

… And impudently move it to their arse —

Nay, cunt itself — and if you will not venture,

They’ll act the same as we, and let you enter

Their pocky false bare cunts, love’s proper centre.

But to speak in the behalf o’ the play

I see you’re mad to know what I have to say:

It is the most debauched heroic piece

That e’er was wrote. What dare compare with this?

Our scenes are drawn to the life in every shape,

They’ll make all pricks to stand and cunts to gape.

Noble spectators, we hope this may be

A play to please your curiosity.

That lady who shall act the best her part

Doth hope at least to have a fucking for it

By some of you, who are spectators come

And have the lustiest pricks in all the room.

“That lot must be spoken by Fuckadilla,” I muttered to myself. “But surely the next bit’s meant for Bolloximian.”

Almighty cunts! whom Bolloximian here,

Tired with their tedious toil, did quite cashier.

From thence to arse he has his prick conveyed

And thinks it treason to behold a maid,

Who oft-times teases with her amorous tricks

And draws whole showers of sperm from labouring pricks

Before they enter. Cheated, he retired

From humid cunt to human arse all fire.

Buggery he chose and buggery did allow,

For none but fops alone to cunts will bow.

“Oh my Gawd!” cried Rob. “Who’s Bolloximian?”

“The king,” I said, “who stands for Charles II in the satire.” And I turned another page.

DRAMATIS PERSONAE

Bolloximian, King of Sodom

Cuntigratia, Queen

Pricket, Prince

Swivia, Princess

Buggeranthus, General of the army

Pockenello, Prince, colonel and favourite of the King

Borastus, Buggermaster-general

Pene and Tooly, The pimps of honour

Fuckadilla, Officina, Cunticula, Clytoris, Maids of honour

Flux, Physician to the King

Virtuoso, Merkin and dildo-maker to the Royal Family

With Boys, Rogues, Pimps and other Attendants

Rob was chuckling at the names. “Hah! Merkins! I remember those from Hugo’s fig-leaf.”

Here let me both interrupt the narrative and reveal how readily heroic couplets can be dashed off.

I warned you, reader, this would make you blush.

Perchance already the hot crimson flush

Of shock and outrage on your cheek you find;

Or else you’re bored out of your little mind.

And so this drama I’ll abbreviate,

Or you’ll be reading it till far too late.

Act 1 Scene 1. Representing an antechamber hung round with Aretine’s postures.

“Eh?”

“Pietro Aretino. An Italian. Famous for his drawings of all the sexual positions.”

Bolloximian: Thus in the zenith of my lust I reign,

I eat to swive, and swive to eat again.

“Swive?”

“Fuck.”

Let other monarchs who their sceptres bear,

To keep their subjects less in love than fear,

Be slaves to crowns — my nation shall be free,

My pintle only shall my sceptre be.

“Pintle?”

“Prick. Again.”

My laws shall act more pleasure than command,

And with my prick I'll govern all the land.

Pockenello: Your grace alone hath from the powers above

A princely wisdom and a princely love,

Whilst you permit the nation to enjoy

That freedom which a tyrant would destroy.

Borastus: May your most gracious cods and tarse be still

As boundless in your pleasures as your will.

“Cods?”

“Balls. As in codpiece.”

May plentiful delights of cunt and arse

Be never wanting to your royal tarse.

May lust inflame your ardent prick with spirit,

Ever to fuck with safety and delight.

Bolloximian: You are my council all.

Pockenello: The bliss we own.

Bolloximian: But this advice belongs to you alone.

Borastus: I do no longer old stale cunts admire —

The drudgery has worn out my desire.

Your grace may soon to human arse retire.

Bolloximian: My pleasures for new cunts I will uphold,

And have reserves of kindness for the old.

I grant in absence dildo may be used

With milk of goats instead of sperm infused.

My prick no more shall to bald cunt resort —

Merkins rub off, and often spoil the sport.

Borastus: I could advise you, sir, to make a pass

Once more at Pockenello’s loyal arse.

Besides, sir, Pene has such a gentle skin

It would tempt a saint to thrust his pintle in.

Tooly: When last, good sir, your pleasure did vouchsafe

To let poor Tooly’s hand your pintle chafe,

You gently moved it to my arse — when lo!

Arse did that deed which kind hand could not do …

Bolloximian: Henceforth, Borastus, set the nation free.

Let conscience have its force of liberty.

I do proclaim, that buggery may be used

O’er all the land, so cunt be not abused.

To Buggeranthus let this charge be given,

And let him bugger all things under heaven.

It does get rather tedious, and from this point I can abbreviate still more, although some stage directions do merit a mention. Such as, A pleasant garden adorned with many statues of men and women in various postures. In the middle is a woman representing a fountain, standing on her head and pissing upright. Soft music is heard. In this scene Cuntigratia and her maids of honour lament the lack of attention from the menfolk and suggest a frigging session instead. Scene changes and discovers the Queen in a chair of state, and is frigged by the Lady Officina, all the rest pulling out their dildos and frigging in point of honour. Their fun is spoilt by the fact that their dildos, made by Virtuoso, are far too small. Then dance six naked men and women, the men doing obedience to the women’s cunts, kissing and touching them often, the women in like manner to the men’s pricks, kissing them, dandling their cods, and then fall to fucking, after which the women sigh and the men look simple and so sneak off.

A comic scene between the young prince and his sister perhaps deserves fuller quotation.

Swivia: Twelve months must pass ere you can yet arrive

To be a perfect man. That is, to swive

As Pockenello doth. Why, as I live,

Your age to fifteen does but yet incline.

Pricket: You know I could have stripped my prick at nine.

Swivia: I ne’er saw it since. Let’s see how much ’tis grown.

(He shows)

By heavens, a neat one! Now we are alone,

I’ll shut the door, and you shall see my thing. (She shows)

Pricket: Strange how it looks — methinks it smells like ling:

It has a beard too, and the mouth’s all raw —

The strangest creature that I ever saw.

Are these the beards that keep men in such awe?

Swivia: ’Twas such, as these philosophers have taught,

That all mankind into the world have brought.

’Twas such a thing our sire the King bestrid

Out of whose womb we came.

Pricket: The devil we did!

Swivia: This is the warehouse of the world’s chief trade.

On this soft anvil all mankind was made.

Come, ’tis a harmless thing, draw near and try.

You will desire no other death to die.

Pricket: I feel my spirits in an agony —

Swivia: These are the symptoms of young lechery.

Does not your prick stand, and your pulse beat fast?

Don’t you desire some unknown bliss to taste?

Come, little rogue, and on my belly lie — (He lies on her)

A little lower yet

— now, dearest — try!

Pricket: I am a stranger to these unknown parts,

And never versed in love’s obliging arts.

Pray guide me, I was ne’er this way before.

Swivia: There, can’t you enter? Now you’ve found the door.

Pricket: Now I am in, and ’tis as soft as wool.

Swivia: Then move it up and down, you little fool.

Pricket: I do, oh heavens, I am at my wit’s end.

Swivia: Is’t not such pleasure as I did commend?

Pricket: Yes, I find cunt a most obliging friend.

Speak to me sister, ere my soul depart.

Swivia: I cannot speak — you’ve stabbed me to the heart.

Pricket: I faint. I can’t one minute more survive.

I’m dead.

Swivia: Oh brother! But I am alive.

Your love grows cold, now you can do no more.

I love you better that I did before:

Prithee be kind.

Pricket: Swie, I did lately dream,

That through my prick there flowed a mighty stream,

Which to the eye seemed like the whites of eggs.

Swivia: I dreamt too, that it ran betwixt my legs.

Pricket: What makes this pearl upon my pintle’s snout?

Swivia: Sir, you fucked lately. Now your dream is out.

All unknown pleasures do at first surprise.

Try but one more, you’ll find new joys arise.

It will your heart with more contentment fill.

Besides, your pleasure will improve your skill.

No resurrection yet? Prithee, let’s feel.

Poor little thing, it is as cold as steel.

Cunticula enters, gets him going again, and wanks him off.

Then Bolloximian and his crew review the recent past.

Bolloximian: Since I have buggered human arse I find

Pintle to cunt is not so much inclined.

By oft fomenting, cunt so big doth swell

That prick works there like clapper in a bell:

All vacuum. No grasping flesh doth guide

Or hug, the brawny muscles of its side

Tickling the nerves, the prepuce or the glans,

Which all mankind with vast delight intrance.

Buggeranthus enters. Bolloximian asks about the army.

Bolloximian: How are they pleased with what I did proclaim?

Buggeranthus: They practise it in honour of your name.

If lust presents, they want no woman’s aid.

Each buggers with content his own comrade.

Bolloximian: They know ’tis chargeable with cunts to play.

Buggeranthus: It saves them, Sire, at least a fortnight’s pay.

Enter forty striplings sent as a gift by the King of Gomorrah. Bolloximian is delighted.

Bolloximian: I love strange flesh. A man’s prick cannot stand

Within the limits of his own command,

And I have fucked and buggered all the land.

Grace every chamber with a handsome boy,

But here’s my chiefest darling of my joy! (pointing to one of the boys)

Come,

my soft flesh of Sodom’s dear delight,

To honoured lust thou art betrayed this night.

Lust with thy beauty cannot brook delay.

Between thy pretty haunches I will play.

Cuntigratia’s maids confront Virtuoso the dildo-maker with his undersized creations. He grovels, until they discover that his own tarse is larger than his products. Fuckadilla toys with it, but to her chagrin he suffers a premature ejaculation.

Next, A grove of cypress trees and others cut in the shape of pricks. Several arbours, figures and pleasant ornaments in a banqueting-house. Men are discovered playing on dulcimers with their pricks, and women with jews' harps in their cunts. Enter, arrogantly, Bolloximian and his entourage.

Bolloximian: Which of the gods more than myself can do?

Borastus: Alas sir, they are pimps compared to you.

Bolloximian: I'll then invade and bugger all the gods,

And drain the spring of their immortal cods.

Then make them rub their tarses till they cry

‘You've frigged us out of immortality’ …

Enter Flux the physician with a tale of woe. The king’s policy had exposed the nation, even the royal house, to an epidemic of STD. The Queen is dead, Pricket and Swivia have the clap.

Flux: Men’s pricks are eaten off, the secret parts

Of women withered like despairing hearts.

The children harbour mournful discontents,

Complaining sorely of their fundaments.

The young who ne’er on Nature did impose

To rob her charter or corrupt her laws,

Are taught at last to break all former vows,

And do what Love and Nature disallows.

Bolloximian: Curse upon Fate to punish us for nought.

Can no redress or remedy be sought?

Flux: To Love and Nature all their rights restore,

Fuck women, and let buggery be no more.

Bolloximian: To be a substitute for heaven at will —

I scorn the gift — I’ll reign and bugger still.

The clouds break forth, then fiery demons rise and sing.

Demons: Kiss, rise up and rally,

Frig, swive and dally,

Curse, blaspheme and swear,

Here are in the air

Those will witness bear.

For the Bollox singes,

Sodom off the hinges.

Bugger, bugger, bugger

All in hugger-mugger,

Fire doth descend.

’Tis too late to amend.

They vanish in smoke. Dreadful shrieks and groans heard and apparitions seen.

Pockenello: Pox on these sights — I’d rather have a whore.

Bolloximian: Or cunt’s rival.

Flux: For heaven’s sake, no more.

Nature puts me in prophetic fear.

Behold, the heavens all in a flame appear.

Bolloximian: Let heaven descend, and set the world on fire —

(to Pockenello) We to some darker cavern will retire.

There on thy buggered arse I will expire.

Fire and brimstone and a cloud of smoke appear. Curtain.

I turned a final page.

THE EPILOGUE, SPOKEN BY FUCKADILLA

Damn ye, my lads! What, never a word to say

In praise or commendation of the play?

Nor me, how well I’ve acted here today?

You look so sottish, now the play is done,

By God, you are so squeamish every one

As if your pricks had all bespurt’d your breeches

For want of cunts — oh heavens how my cunt itches!

It makes me wish for some good brawny arse,

Well hung with a stiff lustily swinging tarse.

Damned feeble pricks — we hate them, they’re but toys;

We’re for the more substantial solid joys

Of a brave stiff romantic swinging prick

That’s twice five inches long and seven thick.

Hard cruel fate, that I could weep an ocean,

When I behold poor pintle without motion

Hanging upon his master’s thighs as dead,

Not having power for to raise its head.

Men when they’ve spent are like some piece of wood

Or an insipid thing, though flesh and blood.

Then fool not nature with you silly hand,

But come to us, whene’er your pricks do stand.

Naked we lie to entertain your tarses,

If you will but forsake men’s beastly arses.

We welcome sodomites made up of sperm

And full of lust, vacation time and term.

Rob had been behind me all along, reading over my shoulder and breathing hard in my ear. “Gawd!” he said. “You know, it isn’t really my cup of tea. Fun, sort of. But so crude.” I could only agree. Yet it was an extraordinary and therefore interesting phenomenon. “Those last lines, though,” he added. “Very appropriate at university! Sam, how old were you when you first read this?”

“Sixteen, I suppose. Maybe fifteen.”

“Then you’re not a dirty old man. You’re a precociously depraved stripling.”

But having reached the end, I realised we hadn’t yet looked at the flyleaf. I turned back to it. Once again, Rob tells me, I went as white as a sheet and, without even being asked, he brought me another Balvenie. For on the flyleaf was written in a neat hand:

Excussum MDCLXXX

in piam memoriam auctoris Com. Rof. nuper defuncti

curante Edwardo Finchio

qui imberbus Pricketi exemplum praebuerat

“‘Printed in 1680,” I translated for Rob, “in loyal memory of the author, the Earl of Rochester lately deceased, under the supervision of Edward Finch who, as a beardless boy, had provided the model for Pricket.’ He must’ve been a relative of John Finch!”

But Rob suddenly realised the time. “Good God! Sorry, Sam. I’ve got to run. Practical in the lab. I’m going to be late as it is.”

Left alone, I sat thinking as I finished my second Balvenie. Then I found my copy of Rochester’s poems, checked a date — he died on 26 July 1680 — and in flipping through it lit by chance on another satire on Charles II.

Nor are his high desires above his strength:

His sceptre and his prick are of a length.

A strong echo there of Bolloximian’s words. Charles got hold of that poem by mistake, and it cost Rochester several months of banishment. That was par for the course. Rochester constantly went too far. Charles constantly kicked him out of the court, but had so soft a spot for the man that he constantly let him back in.

Then I applied myself to the computer. First, who was Edward Finch? Nephew of our John Finch, Alumni Cantabrigienses told me, and younger son of John’s brother Heneage, a lawyer who was later created Earl of Nottingham. Born in 1663, he came up to Christ’s in 1677 at fourteen and took his MA in 1679 at the ridiculous age of sixteen. Powerful strings had doubtless been pulled behind the scenes. Then he was a Fellow from 1680 to 1684, during which time his uncle died. Small wonder, given the circumstances, that he occupied Finch and Baines’s old room. Later he was MP for the university and ended up opting for the straight and narrow. He married late, took holy orders, became a minor composer, and died a prebend of York Minster.

But in his beardless boyhood he had been the model for the Pricket of the play, who was described as fourteen. In 1677, then, he had been noticed, desired, and presumably seduced by Rochester. Easy to guess how they met — Edward’s father was Lord Chancellor and a member of the court. And Edward remained besotted. In 1680, as soon as Rochester was dead and beyond Charles’s reach, he had Sodom printed. An anonymous venture, but risky. Small wonder he hid the book and its dangerous inscription.

Next, Sodom. What about texts? There were two recent print-on-demand editions which, being very cheap, I ordered from Amazon, though I held out little hope for them. There was a dirt-cheap DVD of The Libertine which I ordered too. Otherwise there was only the download of the Paris edition that I had read. It seemed the best there was. I flipped through it again. The text looked much the same as ours, but it was preceded by two long prologues, expanded out of the shortish ones in ours, and followed by no fewer than three epilogues rather than one. They seemed excessive — smut for the sake of smut — and inartistic. Were they genuine?

Much my most useful find, alongside a lot of moderately interesting information, was an academic piece which gave some account of Sodom’s evolution, pieced together from the eight known manuscripts. The earliest was dated by topical references to 1672-3, but was unfinished. Further topical references in later manuscripts showed the text had been revised and completed about 1677. This surely corresponded with our date of 1677 for Edward as a model for Pricket, and with our version printed on Rochester’s death as Sodom, or the Gentleman Instructed.

Another printed version, entitled simply Sodom, a play by the E of R, was published at Antwerp (or so it said) in 1684, the last surviving copy of which was destroyed in the 1830s because of its obscenity. But it had already been copied in a manuscript which was the source of the Paris edition of 1904 that I’d read, the one with the over-long prologues and epilogues. I’d been right — most of them were evidently not Rochester’s work. Then in 1689 yet another version, The Farce of Sodom, or the Quintessence of Debauchery, was published in London. The printer was fined and all copies destroyed, though another manuscript had been copied from it. Ours, therefore, seemed to be not only the earliest complete version but the sole original printed survivor.

I was still roaming the web when Rob came back, and I spent some time bringing him up to speed with Edward Finch, the textual history, and miscellaneous snippets. Such as how at the age of twelve Rochester went up to Oxford where he ‘soon grew debauched’ and took his MA at the even more ridiculous age of fourteen. How he claimed to have been drunk non-stop for five years (“Was it his liver that killed him,” Rob asked, “rather than syphilis?”). The nice remark that Sodom ‘makes Lady Chatterley read like a vicar’s sermon.’

Finally Rob got up. “I’d better put that panel in,” he said, and climbed the ladder.

I sat back, yawning. Tomorrow Sodom must go to Prufrock and the Librarian. That was it, surely, for now. But how wrong could I be? This extraordinary day had not yet shot its bolt.

“Sam!”

“Mmmm?”

“There’s something else in here! Paper. Down the back, almost out of sight. Hang on … Got it!”

He stepped down, blowing dust off. “Beyond me,” he said, peering. “Your baby again.”

There were two sheets covered in crabbed writing, in Latin, the lines of irregular length but roughly centred. It didn’t take long to recognise it.

“It’s a copy of the inscription on Finch and Baines’s memorial,” I said. “Or a draft of it. Yes, it’s initialled H.M. That must be Henry More. He was a Fellow who’d been their tutor, but he outlived them both. We know he composed the inscription. But why should this be hidden away? … Ohhhh!”

“What?”

“Here, at the end. Henry More wrote ‘so that they who in life had united their interests, fortunes, deliberations, and indeed their souls, might likewise in death at last unite their ashes.’ And that’s what’s on the tomb. But someone’s changed the wording to animas, immo vero corpora, underlined — ‘who had united their souls and indeed their bodies.’ And in the margin he’s scribbled sic avunculus meus mihi moriens asseveravit, ‘so my uncle assured me on his death-bed’.”

I’m sure I was grinning like a Cheshire cat. “It must’ve been Edward Finch who wrote that too. He was John’s nephew. He lived in this room. No doubt he’d learnt a thing or two about gay sex from Rochester. He was nineteen when his uncle died. I imagine it went something like this. Henry More gave him this draft for approval, and he wanted to change it. But either he got cold feet and didn’t speak up, or he did and was vetoed. More was happy enough about uniting souls. But it’s hardly surprising if he felt that uniting bodies went too far.”

“So it means Finch and Baines were sex partners,” said Rob. “Good! I’m glad.” He hugged me, and we looked at the pair of portraits with a fresh respect. They looked unselfconsciously back. “I feel,” he added, “like going to Chapel with a marker pen and writing the proper version in.” Instead he went up the ladder again to restore the panel.

“Rob,” I said apropos of nothing. “We’d better keep this stuff under our hats. Sodom and the paper. For the time being. Prufrock ought to be the first to know. And the Librarian.”

“Yes,” he said from on high. “Agreed. Meanwhile, dinner. I’m ravishing”

“You are. In both senses.” I grinned up, loving him. He was beautiful, and ravishing was also a word he’d long ago coined by combining ravenous and famishing.

Dinner was indeed welcome, since we had totally missed lunch. It was as I delivered the first destructive blow to my crème brulée — desserts were by far the best part of Christ’s dinners — that I saw laid out clear before me exactly what I had to do. Back in B4 I returned to the computer, pulled up the long-completed text of my critical edition of Gammer, and put it on a stick. I took it to the college computer room to print off while Rob scanned in Sodom and Edward’s paper. Then we printed them too. As the printer whirred I ran through my plan. Yes, it was right.

“Come on,” said Rob when everything was done. “Bed. Both of us this time. How does it go? ‘Sodomites made up of sperm and full of lust, vacation time and term.’ That’s us.”

Sperm and lust spent, we lay satisfied and intertwined.

“I wouldn’t mind being an octopus,” I said sleepily. “Four times as many arms to hug you with.”

“Only twice as many. If you count legs, which are almost as good as arms.” He demonstrated.

“In that case I wouldn’t mind being a millipede.”

And so I fell asleep, to dream not of Sodom but of two sodomitical millipedes intertwined. Strange creature, aren’t I?

*

Promptly at ten, carrying a folder full of everything, I knocked on Prufrock’s door for my supervision. I hoped that my essay, with which I was not best pleased, would take a back seat.

“Good morning, Sam. Your essay, yes. I have it somewhere here.” He scrabbled among the chaos of paper on his desk.

“Before we get on to that,” I said, “I’ve got some interesting things to show you.” I laid Edward Finch’s paper under his nose. “Rob and I found this behind a panel in Finch and Baines’s room. It’s More’s draft of the inscription on their tomb, amended by Edward Finch. Look at the end.”

He peered at the end, instantly absorbed the meaning, and beamed hugely. “O frabjous day! Callooh! Callay!” he chortled — it was even stranger to hear him quoting Carroll than Kipling. “Long have I awaited something like this! Not in this particular form, nor in such a depository. Merely something to confirm their relationship. But what,” he asked, suddenly looking up at me, “makes you ascribe this to Edward?”

“This. It was with the paper.”

I put the book on his desk, open at the flyleaf. He peered again and goggled, mouth agape like a codfish. This was the second time in a year that I’d witnessed the phenomenon. Unbelievingly he turned to the title page. A shudder ran through him and he leapt to his feet, his glasses bouncing clean off his nose.

“Come to my arms, my beamish boy!” he boomed as he stumbled round the desk and headed in my direction.

Alarmed, visualising the headlines (‘Student ravished by don’), I nonetheless stood my ground. He lunged wildly, pulled me into a bear-hug, and kissed me. Luckily, if he was after my mouth, his aim was bad and it landed, loud and wet, on my cheek. While not the most delectable experience of my young life, it could have been much worse. He let go and stepped back, bumping into the desk. Without his specs, I realised, he was as blind as a bat.

“Sit down,” I said and guided him, still beaming and still quivering with emotion, to his chair. “I’ll find your glasses.”

Find them I did. They had landed not on the thick cushion of papers but, by gross misfortune, on the metal base of his desk lamp. Both lenses were shattered. His euphoria, when I broke the news, subsided like a balloon with a terminal leak. He was instantly helpless. My frustration with the old buffer turned to pity.

“Do you have a spare pair?”

“Errr …” I could see him trying to concentrate on mundane practicalities. “Errr, no.”

“Then you’ll have to order new lenses. Which optician do you go to?”

“Errr …” He was at a total loss.

“Is it nearby?”

“Errr … I believe it is.”

I consulted my mental map for nearby opticians. The nearest I could think of was at the top of Petty Cury, not a hundred yards from the college gate. What was its name? Yes …

“Goggles?”

“That’s it!” he cried. With the prospect of salvation he began to revive. “How could I forget it? Run there, dear boy, I beg you.”

“Best if you phone first and authorise them.”

I found his Yellow Pages, found Goggles, tapped the number into my mobile because I didn’t know how the college system worked, and put it in his hand. First he tried to hold it upside down, but when that was rectified he quite competently ordered new lenses in the old frame which Mr Furbelow would immediately bring in, and please would they (I paraphrase) pull out all the stops.

So I grabbed the old frame and ran to Goggles, who assured me they should be ready tomorrow evening, and ran back to report. Prufrock was sitting exactly as I had left him, staring unseeingly into space.

“Show it to the Librarian,” was all he said. “Now.”

Exactly what I was intending to do. I put book and paper into my folder. “Would you like some music while I’m gone?” Prufrock was a fan of old music and had a good collection of CDs. “Purcell? Right for the period.”

“Yes. Please.”

I riffled, lit on Oedipus which seemed to fit the bill, and put it on.

The Librarian I found busy preparing an exhibition for the quatercentenary next year of the King James Bible, which was translated under the care of Richard Bancroft, Archbishop of Canterbury and another son of the college. But she welcomed me as always and even asked my opinion on one or two matters. With that out of the way, I tentatively embarked on my mission. I hadn’t a clue how this staid and homely person would react. Best to kick off with Finch and Baines again. I showed her Edward’s paper.

“This,” she said having read it, “answers a question often wondered but rarely asked out loud. The gloss was written by a nephew of Finch. I wonder which one. Daniel?”

“No. Edward.”

“How do you know?”

“That paper was behind a panel in the Finch and Baines room. So too was a book that Edward had had printed. This.”

I laid it before her. She opened it at the title page. Like Prufrock, she instantly saw what it was and what it implied.

“Oh my dear paws!” Her glasses nearly suffered the fate of Prufrock’s, but she managed to keep them on board. And two Lewis Carrolls within half an hour! “I’ve heard of this,” she admitted. “Now I must read it.” With that, I felt confident she would take it in her stride. “But Rochester’s authorship is disputed, isn’t it?”

“Look at the flyleaf.”

She did. “Oh my fur and whiskers! 1680! There’s no other surviving copy, is there? No printed copy?”

“Not that I can find.”

“May I borrow this?”

“Keep it. It’s yours. I mean, it’s obviously college property. But I was wondering about the watermark, as a check on the date. And the place of publication. Is The Hague a cover-up?”

She held a page over a light-box. “I think this is going to be easy. GG. George Gill, I’d say.” And a few reference books confirmed it. The paper was made by George Gill at Turkey Mill near Maidstone in Kent between 1676 and 1680.

“That clinches it,” she said. “The date’s all right, and no Dutch printer would use English paper. This was printed in England. I’m wondering …” She pondered. “Oughtn’t we to get Professor Prufrock in on this?”

“He’s seen it. Briefly.” I told her about the disaster with his glasses.

“Oh, poor dear. Well, we ought to get the Master in too.”

She rang him up, and he came round at once. He was, from what little I’d seen, a nice old boy. And being an eminent economist — and more of a human being than many economists I’ve met — he didn’t pretend to know anything about Restoration pornography. To cut a long story short, he was put in the picture and read a number of pages with a raised eyebrow and a faint smile.

“Interesting,” he said. “And if this is the only known copy, have you any idea what it might fetch on the open market? Not that I’m in the least suggesting it should go on the market.”

I hadn’t the foggiest. The Librarian pursed her lips. “I can only guess an order of magnitude,” she confessed. “Ordinarily, with a unique book of this date, maybe £100,000. But its notoriety might push it up to £200,000, should the buyer be a rich and dirty old man.”

“Do I take it, then, that this discovery will cause a stir in the literary world?”

“Undoubtedly.”

“In that case,” said the Master, “we ought, at our leisure, to prepare a press release and consider how best to handle the resulting furore. How many people,” he asked me, “have you and Mr Nethercleft told about it?”

“Outside this room, only Professor Prufrock. He would be here, but …” Again I explained the disaster. “He can’t see a yard. I must go and check that he’s all right.”

“Oh dear. This has happened before. I will send my secretary to see if she can help with his paperwork, and alert the college nurse to assist him with his, ah, personal hygiene.”

That was a relief. Myself, I had no desire to assist in that department.

“You go ahead then,” the Master said, “and I will follow shortly. Meanwhile, may I commend both you and Mr Nethercleft, for your serendipity, and your public spirit, and your discretion? And would you contain the secret until we give the word? Thank you.”

“Oh, Sam!” the Librarian called when I was at the door. Never before had she called me Sam. “I’ve just remembered something in the library store which really ought to be in your room. I’ll get it to you later today.”

Back to Prufrock. The CD was playing a number from Oedipus, ‘Music for a while shall all your cares beguile.’ “How true,” he said. “How very true … Sam, I have not thanked you for your compassion to an old man who is almost as eyeless as Oedipus. For beguiling his cares.”

“That’s all right,” I mumbled. I might have said ‘One good turn deserves another’ but, mindful of Emma’s warning, I did not dare.

“Meanwhile,” he said, “Sodom. What news?”

I brought him up to date. “The Master will be here soon.”

“Sodom …” Prufrock began again. But at that moment the Master came in. Prufrock was less than warm in his welcome. “Master, we are in the middle of a supervision.”

“My apologies. But, having heard mention of Sodom, I will, if I may, sit in.” He found a chair.

“Sodom,” Prufrock repeated. “How does the new text compare with those hitherto known?”

“I haven’t had time to check. Not in detail. Trouble is, there’s no critical edition. Just eight manuscripts, all but one unpublished, every old where. Two at Princeton.” I looked at the ceiling to refresh my memory. “One each in the BL, V&A, and BN. One each at Nottingham, Vienna and Hamburg … Professor, I’ve got a suggestion to make. I’ve finished my first-year dissertation, the critical edition of Gammer …”

His eyebrows went up. “So soon? I was not expecting it until May.”

“Here it is.” I laid on his desk, neatly held together by a plastic binder. “Look at it when you get your glasses back. What I suggest is that I do another dissertation, this time a critical edition of Sodom. Provided I can find funding for microfilms or photocopies of all the manuscripts.”

His watery eyes, normally invisible behind thick lenses, lit up. “My dear boy! But … but …”

“Lancelot,” the Master broke in. “Is this not precisely what the Firkin Fund is for? Should we not, at its meeting next week, ask the Governing Body to release some money?”

For the first time since the disaster, Prufrock beamed. But with the loss of his specs he had somehow lost his authority.

“And how much,” the Master asked, “would cover it?”

Prufrock confusedly did sums in his head. “Eight short microfilms … £3,000 should be ample.”

I breathed a big breath. It had been as easy as that! Provided the Governing Body played ball.

“Thank you,” I said. “But you were asking about the new text. My impression is that it’s very similar to the Paris edition. Except that its prologues and epilogues are fewer and far shorter.”

“Excellent, most excellent!” said Prufrock with renewed enthusiasm. “I have always suspected the authenticity of the Paris versions. They are inartistic, and Rochester was never inartistic. Consider the poetry of the rest of Sodom!”

“Oh, come on, sir,” I protested, dropping instinctively into the tone I’d used with Old Persimmon when I didn’t see eye to eye with him; which, great man though he was, was quite often. “Poetry? It’s verse. Hack verse at that. It’s burlesque, to be hammed up like a pantomime. There’s only one couplet of poetry in the whole thing.”

Prufrock tried to bristle. But minus his specs he was too jellylike. Jellies are not good at bristling. “And which couplet is that?” he asked mulishly.

“Swivia, describing her …” With Prufrock alone I might have used the word, but the Master was here. “Er, describing female genitals —

“This is the warehouse of the world’s chief trade.

On this soft anvil all mankind was made.”

The Master was regarding me with approval. “I like that,” he said. “I like that very much.” And Prufrock did not argue. Perhaps he saw that his enthusiasm had over-ridden his judgment. He relapsed into thought, and suddenly barked out the most unexpected of questions.

“Sam, why are you at Cambridge?”

For a moment I floundered. Then, in a flash of what must have been telepathy, I saw what he was getting at. “To push boundaries,” I declared confidently. “Such as staging Sodom.” Until that moment it hadn’t even crossed my mind.

Prufrock smiled. “Can you, Master, see any cause or just impediment?”

The Master blinked and deliberated. “If you mean in our theatre, no, I can’t. Not in principle. Certainly not as far as language is concerned … these days, anything seems to go. As for nudity … these days, actors seem to strip off at the drop of a hat. But there are still limits, are there not? In a sexual context like this, I feel nudity would be going too far. Just as would real sexual acts. Simulated phalluses, yes, such as were employed — am I not correct? — in ancient Greek comedy. But not real ones. Lancelot, would you agree?”

Prufrock, with more than a touch of reluctance, agreed.

“Sam?” The Master was calling me Sam too!

“Absolutely.” Depraved I might be, as Rob had said, but not as depraved as that. Left to myself, those were exactly the parameters I would follow. “There’s an overkill of bad language, to the point where it becomes meaningless. If you censor that, though, the play loses its whole point. But turn the explicit sex into comedy, and it gains. It’s bold enough without hardcore realism.”

“Agreed, then. Bawdy, but without overstepping the line into the offensive.”