Indelicate Frivolities

5. Sweet William

“That sheep,” I said. “I hope it can smile.”

“Why?” Rob asked.

“If it’s just been shagged by Alex, I’d expect it to be happy. Wouldn’t you?”

The context of this conversation will not be obvious. Here’s how it happened.

*

As Rob and I rattled along the branch line through the suburbs of Birmingham I began to relax. While my own family had dissolved into thin air, I had three proxy families to fall back on. Rob’s and Alex’s I knew and loved, but Hugo’s was still something of an unknown quantity. Although his parents had already been incredibly generous to us, we had met them only briefly, and never before had we been to Pidley Hall, their home just outside Stratford-upon-Avon. Which was where, this June morning, we were now heading.

At the station we were welcomed by the three Spencers and by Alex who was staying with them. They whisked us down to the Royal Shakespeare Theatre where they had found last-minute tickets for the matinee of The Tempest, the Bard’s final and most enigmatic play. But first we went for a snack lunch in the restaurant overlooking the calm waters of the River Avon and the sharp greenery of its weeping willows. While I would never, off my own bat, have burdened Everard and Hermione with my personal woes, they had heard the outline from Hugo, and with great delicacy they got me to spill more beans.

My father and stepmother had long bickered with each other and with me. They had ranted — very loudly — when I teamed up with Rob, they had ranted at my involvement with ‘that acting lot,’ they had ranted at my sordid — their word — productions and publications, they had ranted equally loudly at each other. Now they had reached the final stage. They were separating, selling up, and going their own ways; neither of which, they made clear, would accommodate me. No great sorrow at that, to be honest; rather a degree of relief. ‘Home,’ as one grows older, becomes an increasingly elastic concept. Yet most twenty-year-olds still hanker for some sort of base where some sort of welcome is on offer. Rob, that tower of strength, offered me the shelter of his own family as and when required, and so too did Alex and Hugo, all three with the enthusiastic backing of their parents. Now I had just transferred the last of my possessions to Rob’s home, and we were following up Hugo’s invitation to visit his own.

So far so good. The real and nagging problem, though, was that my family would no longer fund me at Cambridge. With the coming hike in student fees, it was far from clear how I could make ends meet. Christ’s might give me a hardship bursary, or it might not. The thought of having to leave was hateful, and I said so. Everard and Hermione heard my tale with thoughtful sympathy. But the ten-minute bell rang.

“We’ll talk more about this later, Sam,” said Everard. “But now we’d better find our seats.”

I won’t say much about the performance, except that Sir Ian McKellen was Prospero and, of course, brilliant. We were in stitches over the camped-up innuendo in Act II when the drunken Stephano feeds his bottle into the nether mouth of the two-voiced monster. And that prompted Rob, as a relative newcomer to Shakespeare studies, to raise during the interval the long-standing question of whether the Bard had been gay.

“Bisexual, I’d say,” was my reply. “Some of the sonnets addressed to the Fair Youth are fairly explicit. A few people argue that they’re about platonic friendship, or that they’re dramatic fiction, or even that our national poet couldn’t possibly have been queer, could he? But personally I can’t help reading them as autobiographical. Yet at the same time he had it off with women. After all, he got Anne Hathaway pregnant when he was a teenager and had to marry her in a hurry. Then there’s the Dark Lady of the sonnets. And there’s the lovely story that he overheard Richard Burbage — who was one of the top actors of the day — arranging to call on some woman, disguised as Richard III. But our Will got there first and was hard at it when Burbage arrived. ‘Tough,’ said Will. ‘William the Conqueror came before Richard III’.”

The play over, we returned to the restaurant for a cup of tea. There we debated the merits of the new Stratford stage — the technical term is an apron or thrust stage — which had been revamped during the recent alterations to project far out into the auditorium. The justification was that Shakespeare wrote for that sort of stage, with the audience on three sides, as in the reconstructed Globe in London. Which was true, up to a point. But at Stratford the apron is so long that, if the actors are at the front, much of the audience sees only the backs of their heads.

Rob was also shocked that the apron offered so little scope for scenery. Shakespeare, he allowed, intended playgoers to supply the setting from their own imagination. But audiences these days had to work hard enough to follow his language, which isn’t easy. Why make them work even harder by starving them of visual clues? As a designer he firmly believed in the traditional proscenium-arch stage with its huge potential for tangible and credible settings. Authentic performances were all very well, he argued, for people who knew the plays inside out, but surely it was the duty of popular theatres like Stratford to make Shakespeare as accessible as possible, not to keep him obscure. Today’s audience, to judge by its faces and accents, came from all over the world, and many of them were plainly puzzled by what was going on. He had a fair point.

We then did a quick tour of the main sights, for Rob had never been to Stratford. We looked at the half-timbered house in Henley Street where Shakespeare, the son of a glover, was born (in 1564, in case it has slipped your mind). We looked at the Guild Hall, the Grammar School in Church Street where he was educated, and Nash’s House and Halls Croft where his descendants lived. All were heaving with tourists, as they always are in summer, and we went inside none of them. But we did go into the church to pay homage at Shakespeare’s monument.

“Along with the Droeshout engraving in the First Folio,” I explained to Rob, “this is the only certain portrait there is. It was done very soon after his death, when his friends and his widow were still alive, so it must be reasonably true to life. They must have given it their approval.”

“But it’s still not exactly prepossessing, is it?” Everard observed. “Someone said it makes him look like a self-satisfied pork-butcher. But maybe that’s how he did look.”

Our little pilgrimage over, we drove out to Pidley Hall. It too proved to be Tudor and half-timbered, larger than Bumley Grange though by no means a full-blown mansion. True to the Spencers’ socialist principles, the grounds and land were run — very profitably, it appeared — by a co-operative. Once a week in the season the house was opened to the public, unlike the nearby (and much grander) Charlecote Park which belonged to the National Trust and was open every day. Charlecote had been the home of Sir Thomas Lucy who, according to persistent tradition, had a series of run-ins with young Shakespeare over deer poaching; and he paid for it by being caricatured as Justice Shallow in The Merry Wives and Henry IV Part 2.

Pidley, like its owners, was warm and friendly, and over a very good dinner Everard told us something about the history of the Spencer family. Stick-in-the-mud, he surprisingly called it, and indeed (until very recent times) conservative. For generations all the Spencer menfolk had been educated at Hambledon and Christ’s. For generations the name of the eldest son had alternated between Everard and Hugo — changed by the Tudors to Hugh, by the Victorians back to Hugo. For generations — as far back as portraits survived — all Spencers had had flaxen, almost golden, hair. For generations the family had kept its head down. Ever since 1326 when an early Hugo Despenser (“Young Spencer in Edward II — you know all about him”) was put to death in a particularly revolting manner, his descendants had kept out of the political limelight and lived the quiet life of local squires, not even playing any part in the affairs of Stratford.

After dinner Everard gave us a guided tour. One interesting port of call was the gallery, a long narrow room lined with portraits of blond squires — all remarkably similar in face — and their ladies. “But no earlier,” he said, “than the seventeenth century, because the gallery was burned out in 1627. We’ve only one older painting. We found it stashed away in a storeroom, and we’ve no idea who it is or how it got here.”

He pointed to a small roundel on paper, a foot in diameter, which depicted a rather charming boy with dark auburn curls [see the title picture].

“The pundits say it’s Italian work, about 1580.”

“I’d like to think,” said Alex unexpectedly, “that it’s Shakespeare … He looks,” he added, “rather like me.” Indeed, hair colour apart, he did, remarkably so.

“So would I,” said Everard. “But it’s wishful thinking. In 1580 he was sixteen and a nobody. There’s nothing whatever to link him to Pidley. And why should he be painted by an Italian? Much more likely some eighteenth-century Spencer brought this back from a Grand Tour.”

Much more likely. None the less the Cobbe portrait — one of the few with a reasonable claim to depict the Bard — has dark auburn hair. So too, though a less plausible candidate, does the Sanders portrait. And it is on record that the memorial bust in the church originally had auburn hair before it was repainted. But none of that was evidence of anything.

From there to the library, the walls lined high with bookcases and the air heavy with the inimitable smell of old leather. This was territory I loved, and I cried out in delight. But the others claimed weariness and peeled off to bed.

“Knowing you, Sam,” said Rob, “you’ll be here till all hours. Don’t worry about me,” he added generously. “Don’t come up till you’re ready.”

“I’ll be up in a minute too, dear,” Everard called to Hermione. “I’ll just get Sam introduced and then leave him to it. Mercifully,” he went on to me, “the library was spared the fire, so we’ve got a few incunabula and quite a lot of Elizabethan stuff.”

“Was the current Spencer a bibliophile, then?”

“It looks like it. It was an Everard, who seems to have been interested in history and topography. He died in … I never can remember dates, but here’s the family tree … let’s see, that Everard died in 1591. I’ll leave this out in case you need it. And the catalogue’s on the computer — you’ll find a shortcut on the desktop. Oh yes, and this’ll interest you. We’ve a number of Shakespeare quartos too — on this shelf here. When you’ve finished, would you lock up and set the alarm?” He showed me how. “Goodnight then, Sam. Sleep well, when you get round to it. We’ll pick up our chat about your future tomorrow, but no hurry to get up in the morning.” And off he went.

Left to myself, I browsed through the quartos. A word is needed here about the publication of Shakespeare’s works. The definitive collection is the First Folio produced in 1623, seven years after his death. It contains the canon of his thirty-six plays, of which exactly half had not been published before. Had it not been for this labour of love by his friends, these eighteen plays, including Macbeth, Twelfth Night and The Tempest, would have been lost for ever. But the other eighteen had already been published in Shakespeare’s lifetime, in slim individual quartos most of which were carelessly edited and crudely printed. Many survive in only a small handful of copies. Probably all of them, in those days before copyright, were done without his consent. In contrast, his four volumes of poems are meticulously printed, evidently under his own supervision.

For a private library the Pidley quartos formed an almost incredible collection. They numbered fifteen, bound not quite identically but similarly, as if by the same binder but at different dates. Plays, in Tudor times, were down-market publications, almost an equivalent of cheap paperbacks today. They were normally sold unbound at sixpence apiece, and it was up to the customer to have them bound should he wish. All but two of the Shakespeare quartos here were plays, the others being his poems Venus and Adonis and The Rape of Lucrece.

Then something odd struck me. All fifteen were published between 1593 and 1600. I went to the computer and checked with Wikipedia. Yes. Represented here was every single work of Shakespeare that appeared down to 1600, and not one that appeared thereafter. Were there later ones on another shelf? No. The catalogue confirmed the total really was fifteen. Its entries were listed by date of publication. Before the quartos came a whole string of books, many of them first editions of enormous interest and value but of no present concern to me, including such historical and topographical gems as Camden’s Britannia, Leland’s Assertion, Stow’s Annals, Holinshed’s Chronicles, a Sebastian Münster, Joscelyn’s De Excidio, an Olaus Magnus. This series ended in 1591 and was clearly acquired by the bibliophile Everard who died in that year. Then came the fifteen Shakespeares. But after 1600 there were no entries at all — evidently the current Spencer was not interested in books — until the 1640s, when such godly authors as Sir Thomas Browne, Jeremy Taylor, Bunyan and Milton began to appear.

I checked the family tree. On his death in 1591 Everard the bibliophile was succeeded by his son Hugh, who was born in 1560, married in 1587, and died quite young in 1601. With his death the influx of quartos abruptly stopped. During his ten years as squire of Pidley, therefore, Hugh added fifteen books to the library, and every single one was a Shakespeare. The conclusion had to be that he was a Shakespeare fan, and that he had bought them himself. They were hardly gifts from the author — who would give away shoddy pirated copies of his own work? — and none of them had any handwritten dedication. But that reminded me of an entry in the catalogue, embedded in the middle of the earlier historical and topographical collection, which I had noticed the first time round but had not bothered with.

I looked it up again. Geneva Bible, London 1578, with manuscript verse to H.S. from W.S. 1579. I was instantly on full alert. Among all those priceless rarities, this book was an odd man out. The Geneva Bible, first published in full in 1560, was a mould-breaker — far more so, to be honest, than the King James Version. It was the first bible in English to divide the text into numbered verses and, much more important, the first to be mass-produced and sold at a price of less than a labourer’s weekly wage. It went through hundreds of editions. It is not therefore a rare book, even today.

As a bible, then, it seemed to hold little of interest. But the verse … In my present state of mind there was promise in anything to do with H.S., and special promise in anything to do with W.S. The book, when I located it on the shelf, proved to be squat and thick, about 8½ inches high, and inside the front cover, in careful handwriting, were the words:

H.S.

This holie booke perused,

Each iote and tittle scand,

The truth heerein diffused

Plaine shall you understand.

W.S.

August 1579

Hmmm. Was that promise empty after all? It was likely enough that H.S. was Hugh Spencer, who in 1579 was aged nineteen. But it was also likely enough that W.S. was merely a relative presenting him with a bible as he entered manhood. I consulted the family tree, which was very detailed. No, that wasn’t the answer. At the right period there was no W. Spencer at all. Well, the initials were hardly rare — there must have been thousands of W.S.s sculling around England at the time. True, one of those thousands was William Shakespeare. But why should the fifteen-year-old son of a humble glover give a bible to the son of the squire? I looked again at the handwriting. It was in secretary hand, the usual script of the day, without much character, neatly done in formal copy-book style as if by a schoolboy carefully remembering his writing lessons. Interesting, but proof of nothing.

Old bibles like this often contain handwritten notes. The blank endpapers and the blank sheets facing the title pages of the Old Testament, Apocrypha, New Testament and metrical psalms were a standing invitation to insert pious texts or records of family births and deaths. I inspected them, but all were empty. The book seemed hardly used, and apart from some foxing — those little brown patches caused by mildew — it was in excellent condition. But yet, but yet … By the pricking of my thumbs, I misquoted to myself, something cryptic this way comes.

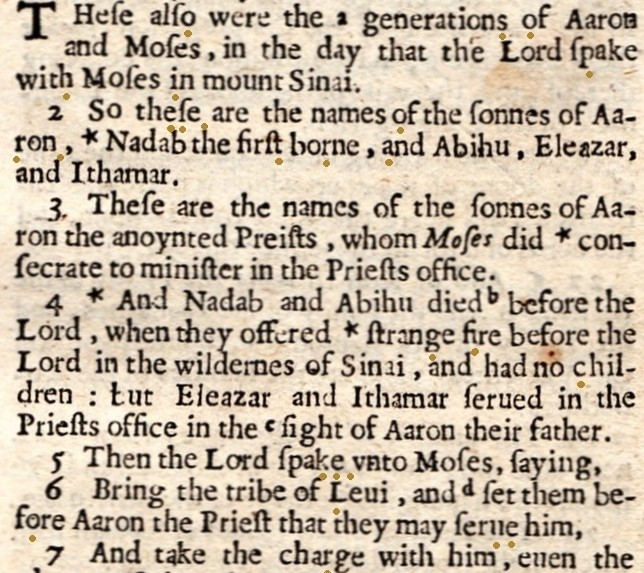

That verse niggled at me. This holy book perused, each jot and tittle scanned, the truth herein diffused plain shall you understand. Taken at face value, it was unremarkable. Yet did it hold a hint of something out of the ordinary? Was I astray in smelling a riddle in it, a coded instruction? Each jot and tittle. Was that a clue? Jots and tittles meant tiny little things — serifs on letters, dots over i and j. The phrase came somewhere in the Gospels, didn’t it? Google quickly located it at Matthew 5:18, and I looked it up in the Geneva Bible. Till heaven and earth perish, one iote, or one title of the Law shall not escape. Still not promising, and that page was as empty of annotations as the rest. I turned back at random, large chunks at a time, through the Apocrypha, through the minor prophets, through the major prophets, through the poetic books, through the histories, into the Pentateuch, and every page I looked at was clean. Until …

I nearly fell out of my chair. I had landed in chapter 3 of Numbers, and that page had been tampered with. I had to look hard to see them, but under various letters, even under spaces between words, were dots of sepia-coloured ink. Were these the jots and tittles?

Grabbing pencil and paper, I feverishly copied the dotted letters in sequence. As I read the result through, the hair crawled on my neck. Not only did it make sense, but it was in blank verse: … osophies or tragicke louers foyled of their intent by unrespited grudge of destinie.

I flipped forward. The dots continued to near the end of Deuteronomy and there stopped. Holding my breath, I turned back to the start of Genesis. That, of course, was where I should have begun, because that was where everything began — In the beginning God created the heauen and the earth. And there too began the dots. Mechanically I wrote the letters down … and found myself staring at a title, the author, and the opening of the text.

swete william a plaie by will shakspere churche strete lucy soon shall we haue him pinioned in the stockes

No capitals, no punctuation, no line breaks, typical unregulated Tudor spelling, but, as far as my numbed brain was capable of absorbing it, clear enough. I desperately wanted to carry on, but found that I could not. Not by myself. I had to share my discovery. And reaction was setting in … throat dry, heart palpitating, mind and belly churning.

Stagger upstairs. Into our room, shake Rob viciously, bleat “Library! Now!” Hammer on Hugo and Alex’s door, open it to croak the same message. Feel a surge rising unstoppable in my gullet. Dive into a nearby bathroom, crouch over the great white telephone to God, heave out my soul. Find Rob beside me, his arm over my shoulder, offering a glass of water to wash my mouth. Turn round to sit on the floor, leaning back against the loo. The world fell slowly into place. Hugo and Alex, in a barely decent state of undress, were kneeling in front of me. Everard and Hermione, dressing-gowned, hair on end, were hovering anxiously in the doorway.

“He said something about the library,” Rob replied to their raised eyebrows.

“Fire?” asked Everard in alarm.

“No,” I managed. “Shakespeare. A new play.”

And, tight in Rob’s arms, I dissolved into tears. Faintly I heard gasps and a clamour of disbelief.

“If Sam says he’s found a new Shakespeare play,” declared Rob stoutly, “then he has. But we’re not going to look at it till he’s ready.”

Here I must annoyingly interrupt the narrative with a word of excuse for my weaknesses. Undiscovered plays by Shakespeare simply do not exist. Scholars have traced his contribution to a few collaborative ventures such as Sir Thomas More. He wrote Love’s Labour’s Won and had a hand in Cardenio, but both are lost and the most determined efforts have failed to unearth either. Not a single new play wholly by Shakespeare has emerged since the publication of the First Folio in 1623. The starry-eyed may dream of finding one, but they never do.

Until, that is, now. For over four hundred years the thing had been sitting in full view on a shelf in the library of Pidley Hall, within two miles of Stratford, waiting for some geek to stumble across the key to its simple code. And that geek had turned out, by chance, to be Sam Furbelow. A very good reason to sob my heart out with no sense of shame whatever. And another good reason was the contrast between the sterile chill of my dismembered home and the unstinted warmth of Pidley — not just Rob’s ever-present love, but the deep fellowship of Alex and the Spencers. Every one of them understood the chaos in my mind, both strands of it, and every one of them supported me.

“Quite right too,” I heard Hermione say. “But I’m going to make some coffee. I’ll bring it upstairs.”

“No,” I managed again. “Library. Give me five minutes and I’ll be all right.”

And after five minutes I was all right, more or less. The boys, having flung on more clothes, solicitously shepherded me downstairs. Hermione brought in a tray of coffee and biscuits. Caffeine began to restore me to a more even keel. I explained how the dates of the quartos, suddenly stopping at the time when Hugh Spencer died, suggested that he had been a Shakespeare fan. I showed them the verse in the bible, which everyone pored over — but only after I had forbidden them to bring coffee cups anywhere near. It had been given, I pointed out, to an H.S. who was very probably Hugh Spencer by a W.S. who could just conceivably have been William Shakespeare. I explained how the jots and tittles worked. I showed them my transcription of the first page, which proved that W.S. was not just conceivably William Shakespeare, but really was William Shakespeare:

swete william a plaie by will shakspere churche strete lucy soon shall we haue him pinioned in the stockes

There were yells of incredulous delight. Hugo and Alex bumped fists. Everard and Hermione danced a little jig. Rob simply squeezed me.

Meanwhile I did a quick scribble. “Put into modern form,” I said, “it looks like this.”

Sweet William

A play by Will Shakespeare

Scene Church Street.

Lucy: Soon shall we have him pinioned in the stocks!

“Sam, oh Sam!” cried Everard, hugging me. “You marvel! You miracle! You genius!”

“That’s as far as I’ve got,” I said apologetically. “It’s going to be quite a job to transcribe it. And it must have been a monumental job to dot it in. No wonder he didn’t bother with capitals or punctuation or line breaks, and kept stage directions to a minimum.”

“A bare minimum,” Everard agreed, looking again. “Church Street? Stratford?”

“Probably. No doubt we’ll find out.”

“And Lucy’s obviously the first character to speak. Sir Thomas Lucy, do you suppose, young Will’s arch-enemy?”

“Likely enough. We’ll see.”

“So it’s a juvenile work.”

“Yes. The best part of ten years before his next. We mustn’t expect a Hamlet.”

“How do we tackle it, then? You’re in charge.”

“Are you happy,” I asked generally, “to keep at it all night?”

Needless to say, they were. “Happy to keep at it all tomorrow if we have to,” said Everard. “Well, all today, given the time.” It was almost one o’clock. “When my secretary turns up I’ll get her to cancel my appointments. Everything else takes second place.”

So I organised three teams, one on the library computer, the others on laptops we brought down. Hugo dictated the dotted letters and spaces to Alex who typed them in. At intervals Alex put the resulting chunks of raw unedited text onto a stick which he passed to Hermione and Everard, who got it into lines and added capitals and punctuation as appropriate. Their results came in turn to Rob and me, who further edited it with expanded stage directions and added numbers to scenes and, tentatively, to acts. It took time to get into the rhythm. If Hugo was dubious whether a mark was an intentional dot or an accidental spot of foxing, a question mark had to be inserted. Sometimes he lost his place, and took a while to recover it.

But we ploughed steadily ahead. It rapidly became clear that Will himself was a central character, and that Hugh Spencer was another. It also became clear that some of the subject matter was quite uninhibited. In his maturity, Shakespeare was happy to employ sexual, even gay, innuendo. Here, in his youth, he went beyond innuendo, though nothing like as far or as crudely as Rochester did later in Sodom.

Our quiet mutterings might be interrupted by an “Oh my God!” or a snigger or even an outright bellow of laughter. There came a point when Hermione positively screamed. She and Everard were the first on the production line with a real chance of reading the text as sentences rather than as strings of letters. “His portrait was painted!” she shrieked. “By an Italian! On a roundel!”

We abandoned our tasks and crowded round her screen. “Yes!” cried Everard. “In left profile! And he had sorrel hair! Meaning dark auburn! Alex, you were right after all! Oh, brilliant!”

He cantered off to the gallery. Hermione seized the chance to renew the supply of coffee, and some of us seized the chance for a pee. Everard came back with the portrait which he propped in front of us. It was good to have Will — a now-authenticated Will — overseeing our labours, and we somehow felt that he was chuffed to see his own labours unveiled at last, more than four centuries on.

“How far through are we?” I asked Hugo.

He compared the thickness of the pages already done with those left before the end of Deuteronomy. “Half way,” he said. “Or a bit more.” It was now after five. “But I’m going cross-eyed with these damned dots. Alex, dear Alex, can we swap over?”

Back to the grindstone. Soon afterwards Hugo spluttered. Perhaps he was better than Alex at reading the raw text he was handling. “Oh, dirty!” he declared. “If I’ve got it right.”

“Filthy!” Everard agreed when it reached him.

“But very funny!” Rob cackled when it reached us.

Before long it became clear why Will had chosen so laborious a method of perpetuating his work. The play had been written not for the stage but for Hugh and himself alone, as a private memento of their fun and games. And Hugh, fearful that his parents might discover his copy, had insisted that it be disguised. The current Spencer parents, thank goodness, were infinitely less prudish.

Finally, at half past eight, with another bellow of laughter, we reached the end. Knackered but fulfilled, we sat back and looked at each other. “I don’t for a moment think it’s a fake,” I said. “How could it have been planted? But it needs to be authenticated scientifically, the sooner the better. And right now,” I ventured to Hermione, “might I suggest a bite of breakfast? Meanwhile I’ll print off six copies so we can read it end to end while we’re eating.”

“I second that,” Everard said. “But give it me on a stick and I’ll print three copies in the office while you do the other three here. My secretary’ll be here any minute, and I’ve got to square her. And I think I’d better put Will and the bible into the safe, don’t you? They’re worth umpteen million pounds more than they were a few hours ago.”

And so it came to pass. Hugo and Alex went off to help Hermione with breakfast, Everard went off to organise security and secretary, and Rob and I collated the printed copies. Before long, over our bacon and eggs and toast and marmalade, we were reading Sweet William properly for the first time.

By now the impatient reader will be feeling left out and wondering what the heck this damn play is about. So here it is in full, modernised in spelling and with punctuation added. I have also inserted the list of characters and relatively generous stage directions. Will had given no more than the briefest of pointers to who was who and what happened where. Apart from the labour of dotting it all in, this was no doubt because the play was for his and Hugh’s eyes alone. It was a more or less factual account of their own deeds. They already knew the background and for that reason did not need detailed directions. But modern readers do. My additions, therefore, are what I have deduced from clues in the text.

The following — if I may indulge in a little advertising — is essentially the same as you’ll find in Sam Furbelow (ed.), Sweet William: an acting edition (Cambridge University Press, 2013), 74pp., paperback £7. Should you want a long introduction and copious and (I hope) scholarly annotations, may I modestly refer you to Sam Furbelow (ed.), Sweet William: a critical edition (Cambridge University Press, 2013), xvi + 312pp., cloth bound £50, paperback £25?

*

Sweet William

A play by Will Shakespeare

Cast in order of speaking

Sir Thomas Lucy, a landowner and justice

Another justice

Will Shakespeare, a boy

Hamnet Sadler, a friend of Will

Hugh Spencer, a Cambridge undergraduate

An officer of the town watch

A fornicator

Lady Lucy, Sir Thomas’s wife

Toby, a youth

A second watchman

Benvolio Figino, a Milanese artist

A farmer

John Symons, leader of Lord Strange’s Men

Non-speaking parts

Perkin, a farmhand

Perkin’s girl

Anne Hathaway

Sundry servants, schoolboys, townspeople and players

The play is set in and near Stratford-upon-Avon in the summer of 1579

ACT I SCENE 1

Church Street, outside the Guild Hall and Grammar School. At one side are the town stocks. Hugh Spencer, aged nineteen, finely dressed and golden-blond in hair, leans unobtrusively against a wall. Enter two men of the town watch escorting a prisoner, followed by Sir Thomas Lucy and another justice. Behind Lucy is a servant carrying a large basket which he sets down near the stocks.

Lucy. Soon shall we have him pinioned in the stocks!

Justice. For shame, Sir Thomas! Innocence is presumed

Ere guilt be proved.

Lucy. Pah! Guilt is in no doubt.

Why waste a precious hour in proving it?

Exeunt towards the Guild Hall, the servant making a rude gesture behind Lucy’s back. The church clock strikes five. It is the end of term and satchelled boys spill out of school, laughing and larking. Most run off, but Hamnet Sadler and Will Shakespeare linger. Will is fifteen, with dark auburn hair. They do not notice Hugh.

Will. So, schooldays over! Tyranny no more!

An end to despot masters! “Parse it, boy!”

“Subjunctive follows always after cum!”

“Give me the gerund! Tush, if you think it so,

Your head’s a colander! Hamnet, the rod for you!”

Hamnet bends over and Will pretends to thrash him.

Hamnet. There’s but one reason, Will, why boys have bums

—

To offer targets at which rods may aim.

To spare the rod, they say, is to spoil the child,

But spoiled I’d rather be, if rod be spared,

For bums heal slow when flesh is black and blue.

Will. Forget not, Hamnet, as we’re well acquaint,

There is another rod which aims at bums.

But while that rod may hurt when first applied,

Continued plying soothes the sorenesses

And leads both parties straight to ecstasy.

Hamnet, chuckling. Prevent one hurt by sparing of the rod,

Prevent the other by more constant use!

Well, I applaud such constancy of sport

As we have followed for the past twelve months

And will I trust pursue as time allows.

What next for you, Will? Are you articled

Unto your father, as I am to mine?

Will. Nay. Since his illness struck he takes no more

Apprentices. But he has found me place

With an attorney, where I soon shall be

Engrossed with affidavits, testaments,

Ex alia parte, nolle prosequi.

But that new drudgery does not drag me in

Until next Monday. Meantime I am free.

Hamnet. But for this week I shall be occupied

At Alcester with my father. Once returned,

Let us two meet and ply our rods again!

Exit Hamnet. Hugh steps forward.

Hugh. Well met, young Master Shakespeare!

Will, eying him dubiously but bowing slightly. My lord?

Hugh, laughing. No lord am I, nor knight. My humble name

Hugo Despenser, or in more common tongue

Hugh Spencer, son of Pidley Hall hard by.

At your unstinted service here I stand.

He bows formally.

Will, puzzled. My service, sir? What would you do for me?

Hugh. Talk to you, Will, and listen. Here, let’s sit.

They perch side by side on the stocks.

A further morsel, Will, about my state.

I am at Cambridge University,

A member of Christ’s College, and it wants

Another term before I graduate.

There I have friends aplenty, but when here

Vacation time hangs heavy on my hands.

I would be friend to you, if you to me.

Will. Why me? I stand a league below your rank.

If not a knight, yet full esquire are you;

Yeoman am I, not even gentleman.

Hugh. What matters rank where friendship stands instead?

Will, I have heard much of a certain lad

And would know more about his temperament.

Will, cautiously. How have you heard?

Hugh. By asking round about,

And every Stratford gossip-tongue has spoke.

Shall I describe his jests, his bookish bent,

His skills and arts and venturous cast of mind,

And ask if you discern of whom I speak?

Will nods slowly.

Who knows his herbal like an apothecary,

And who devours all books that come his way?

Who when the players bring interludes to the town

Beleaguers them with questions on their craft?

Will coughs modestly.

Who chased the parson from the pulpit once

By penning there a piglet?

Will begins to grin.

Who at the butts

A pretty marksman is, and who has killed

Coneys past number in that termagant

Sir Thomas Lucy’s fields — yet, marvellously,

Without discovery or reckoning?

Will, slyly. And did you hear that he has coneys killed

In Spencer fields, without discovery?

Hugh, laughing. Nay, I did not, but I forgive him that.

… And who full three years since, his voice still shrill

And belly surely smooth, did lay a wench?

Will, defensively. But got her not with child. He had no seed.

And when it flowed, less than a twelvemonth since,

He laid no wenches more.

Hugh. And that because …?

Will. Wenches in passion oft conceal their months.

Who would wish bastards more on this teeming world?

Hugh. A wise young head with such philosophy!

… And who with Hamnet, as I heard but now,

Has learned the second cause why boys have bums?

Will jumps in alarm. Hugh lays a reassuring hand on his knee.

I too have wenches laid, my modest Will.

I too have plied my passioned rod on boys.

No censure then from me, but rather praise,

So it be done by full and free consent;

For youth, long injured by the master’s rod,

Has earned the right to wield his own in joy.

… So, Will, may we be friends?

Will, wholly won over. Indeed we may!

Enter the watch dragging the same offender to the stocks. A crowd begins to gather.

Officer. Your pardon, sirs.

Hugh and Will stand aside as the man is locked in.

Will. For what crime is he here?

Officer. Fornication.

Will. Not adultery or rape?

Officer. Oh no, sir. Those are met with worse than stocks.

Enter Sir Thomas Lucy, who observes the scene with satisfaction.

Lucy, to the crowd. Behold a fornicator, and his just deserts!

(Pointing to the basket) Here, sirs, amuse yourselves with putrid

pears.

Nobody makes a move, many shaking their heads and some, Will included, making rude gestures at Lucy behind his back. Lucy shrugs and himself flings a couple of pears at the fornicator’s face. Exit with the watchmen. The crowd drifts away. Left alone, Will and Hugh go up to the fornicator. Will wipes the worst of the mess from his face, Hugh slips a coin into his pocket.

Hugh. Your only crime, my friend, was being found.

Fornicator. My thanks, kind sirs. And may you ne’er be found!

Hugh and Will move away.

Hugh, softly. If, Will, you’re partial to my company,

Let us seek out a solitary spot

Such as the meadow by the river’s brink.

There let us talk, and learn more of each other.

Will. And also swim, and see more of each other?

And having swum, try out each other’s mettle

By preying coneys on Sir Thomas’ land?

Hugh, laughing. Yea, all of those, and more, if so we may.

Will. Then let us first betake us to my house,

To arm ourselves against the coming fray.

Exeunt.

ACT I SCENE 2

A flowery meadow beside the River Avon. Enter Will and Hugh with bows and a quiver. Will has exchanged his school satchel for a bag with towels and cloaks. They sit down in the grass. Hugh, searching for a topic with which to break the ice, looks around.

Hugh. Of all these blooms I fear I know but few —

Such common ones as flourish everywhere —

The yellow pissabed and butterflower,

The purple thistle and the poppy red,

The white and golden daisy — all distract

The eye of the beholder. For the rest,

Less gaudy, pray instruct my ignorance —

What virtues do they have medicinal?

Will. Were I to lecture you on all the rest

We would be here past sunset, for you’ve named

None but the largest and most evident.

For smaller blooms of rival brilliance

Search closer in the sward. Some please the eye

And salve the body — this, the speedwell blue,

Cleanses the blood, and this red pimpernel

Smooths and enlivens the complexion.

Others, less bright, do rather please the nose —

Here, meadowsweet which, strewn upon the floor,

Suffuses a whole house with fragrances.

For the mouth, the humble sorrel’s arrow-leaf

Gives spice to salads and allays the thirst,

And horehound bites more bitter on the tongue …

He crushes a leaf and holds his fingers out to Hugh.

Hugh, sniffing. Faugh! Noxious! Rank! A stench of stale sweat!

Will. Yet is a sovereign cure for coughs and gout.

But that’s enough. Were I to persevere,

You’d mark me down as a narcotic herb

Whose only virtue is to summon sleep.

Hugh. No slumbers does your dulcet voice induce.

But of these flowers, which delights you most?

Will, pointing at Hugh. This above all, this golden flower de luce!

Hugh, much pleased. By eye, or nose, or mouth?

Will, grinning widely. I trust, by all.

Hugh abruptly seizes Will by the shoulders and gives him a quick kiss.

Hugh. I love your urchin face, your devil smile,

Your cherub curls, yea, I love every inch,

And fain would feast my eye on inches more.

He puts a tentative hand on Will’s crotch.

Will, giggling. Inch? You debase me! Not by inchmeal I,

Whate’er your piddling Pidley pintle be!

Hugh. Inch and a half, then? May I measure you?

Will. Give you an inch and you shall find a yard!

Hugh. A yard?

He looks cautiously around.

Should someone pry, our yards being up,

Into the river straight. ’Twill cool us off.

A modesty curtain descends. Behind it, Will undresses. Hugh stands admiring him.

Hugh, impressed. A yard indeed! No yard in length, but yet

A noble weapon brandished high with pride.

Looks more closely.

And ere the spring these downy seedling-shoots

Shall burgeon into bushy thicket-patch

And make a full-blown man of you.

Will. And yours?

Your codpiece coppice? Let me make assay.

Hugh undresses.

Will. Oh god of woodlands! Ne’er a coppice here!

Forest of Arden, rather, dense and spread

Hither and yon as far as eye may see.

And in its midst a doughty trunk of oak,

A peerless heaven-pointing king of trees.

Hugo Despenser, you dispense delights!

Hugh. Dispense I would, but here I do not dare.

We must await some lonelier trysting-place

Within four walls. Come, let us cool our ardour.

Hand in hand they leap into the river. Loud splashes are heard, and much laughter. Hugh is seen lunging as he ducks Will, and vice versa. Curtain.

ACT II SCENE 1

A country road. Behind, a few trees and a signpost pointing to Stratford. The day is dying. Enter Will and Hugh cloaked and hooded, Hugh carrying the bows, Will two dead rabbits.

Will. Easy as robbing babies in the cradle!

Hugh. Of which I trust that you are innocent.

Will. I am, for what do babies have to rob?

And babies are all innocent of wrong

Whereas Sir Thomas’ sins cry out … Oh heaven!

Speak of the devil and he will appear!

Enter, from the opposite direction, Sir Thomas Lucy.

Lucy. You, boy! Those coneys are not yours, I ween.

Will. Pardon, your honour, but they are mine now.

Lucy. Never have they been yours, and are not now.

Are not these acres and their coneys mine?

Hugh. Nay, sir, this highway is a common road,

That side lie your fields, this side Spencer lands.

Lucy. Even on this side they’re not yours to take.

Hugh. They are, and most assuredly not yours.

May I not coneys kill on Spencer ground?

May I not those coneys give to whom I will?

Throws back his hood.

Lucy, nonplussed. Pardon, young sir. I knew not who you were.

Exit, reluctantly and suspiciously. Will and Hugh laugh.

Hugh. Pinch-penny niggard! What are two coneys lost

From all his thousands? Justly is he mocked.

Will. Even by his lady when she cuckolds him.

Their town-house butts on ours, and oft we hear

Her minions calling when he is from home.

Exeunt towards Stratford.

ACT II SCENE 2

Henley Street, with the Shakespeare and Lucy houses abutting. Each has a door, a shuttered window beside it, and an unshuttered window above. To one side, a water butt. Enter Will carrying the rabbits and Hugh the bows.

Will. Here must we part. Fain would I bring you in,

But should my father spy us entering

So late together, we would be undone.

Then farewell, gentle Hugh. We meet again

Tomorrow morning. May it tide as well

As has today.

Hugh, disappointed. Amen to that. Farewell!

They kiss furtively. Will goes in and shuts the door. Hugh sighs.

The choicest pearls are gathered, so men say,

In tropic seas of far Taprobane,

Yet blooms a choicer here on Avon’s shore.

His soul I begin to know, and love it well,

But would I knew his body, knew it close.

My mounting passion frets at this delay.

A candle is lit upstairs in the Shakespeare house.

But soft! A light in yonder window breaks.

Is that his chamber? Will! Canst hear me? Will!

On one knee, he strikes the pose of a pleading lover.

Show yourself, star of Stratford! Let your glow

Irradiate this lesser planet’s gloom!

Lady Lucy appears at her upper window, and Will at his.

Lady Lucy, puzzled. Toby, is’t you?

Hugh, looking up at her. Nay.

Lady Lucy. Then begone, buffoon!

She throws the contents of a pisspot at him, and disappears. Hugh splutters. Will, giggling, drops a towel. Hugh dips it in the water butt and scrubs himself.

Hugh, whispering. I must come up!

Will. And I already am!

Hugh, looking around, spots a ladder lying on the ground outside the Lucy house.

Hugh. But this will open up the path to heaven!

He sets the ladder below Will’s window, climbs up, and disappears inside. Grunts are heard. All lights go briefly off to indicate the passage of time. Enter surreptitiously Toby, an otherwise anonymous youth. Seeing the ladder and hearing the grunts, he grins.

Toby. So I am not the only one abroad!

He moves the ladder to Lady Lucy’s window and climbs it.

My turtle-dove, my popinjay, ’tis I!

Lady Lucy, coming to her window. My peacock, oh my bird of paradise!

Toby disappears inside. Squeals are heard. The lights go briefly off. Enter the watch with lanterns. Under Will’s window, hearing the noises, the second watchman grins knowingly, but the officer sniffs in disapproval. Under Lady Lucy’s window, the same.

Officer. Take up this ladder! To the pinfold with it!

Second watch. And cast a dampening cloud on harmless play?

Officer. On sinful play. This ladder is a lure

Alike to felon and philanderer.

Take it, I say! Remove temptation!

The second watchman shrugs and picks up the ladder. Exeunt. The lights go briefly off again. Hugh and Will appear at their window. Hugh, now fully dressed, begins to climb out.

Hugh, looking down. The ladder which admitted me is gone,

Embezzled by some misbegotten thief!

But ’tis not far, ’tis not beyond my scope.

Farewell again, dear friend, yet dearer now

He lowers himself by his arms and drops to the ground. Hearing the noises from the Lucy window he points to it, grinning up at Will and thrusting with his hips. But, hearing footsteps, he hides behind the water butt. Enter Sir Thomas Lucy, who also hears the squeals.

Lucy, to himself. Who is it this time? Shall that wife of mine,

That so-called wife, in truth that courtesan,

Ne’er learn the virtues of the marriage bond

Or the sublime rewards of nuptial love?

He lets himself into his house. Soon are heard a bellow of rage, a gasp and a shriek. Toby appears at the window wearing only shirt and stockings. He throws out his breeches and tries to climb down but, finding the ladder missing, is grabbed by Lucy and hauled back inside.

Toby, pleadingly. Save me, your honour, I can all explain.

Lucy. You whoring milksop, beardless paramour,

More I demand than explanation.

Toby. Then restitution, sir — I can pay well!

My purse is — oh! My purse is on my belt

And lying with my breeches in the street!

Lucy. I’ll fetch it up and you shall pay your all.

Lucy leaves the window. Hugh darts out, removes a purse from the breeches, hefts it so that it chinks, and jumps back into hiding. Enter Lucy from his door. He investigates.

Here are the breeches, but no purse is here.

(Shouts up at the window) False lying miscreant! You shall pass the

night

Confined. Tomorrow is the court convened,

And though your guilt cries reeking up to heaven,

You there shall answer to the justices.

He spots Will listening.

And you, boy, spying on your neighbour’s plight,

If e’er I find you plant a footstep wrong,

The stocks for you yourself, without defence!

Will shrugs. Lucy storms into his house and slams the door shut. Hugh emerges and throws the purse up to Will. They laugh delightedly.

Will. Tomorrow if Sir Thomas sits in court

Judging malfeasors and adulterers,

His lands lie open, and keepers he keeps not

Beyond his own mean self. Let us descend

Once more on his preserves, and raise the stakes.

This time, my Hugh, we shall a deer attempt.

Hugh, grinning. So shall we meet before the clock strikes

eight,

At the far bridge end. I shall bring the bows

And some conveyance to lug home our spoils.

Blowing kisses to each other, Hugh leaves and Will withdraws. Curtain.

ACT III SCENE 1

The same country road near Stratford. Enter Will and Hugh, the latter pushing a handcart on which lies a dead deer covered by a blanket, its head and horns sticking out. A wheel is squeaking.

Will. A noble chase! The finger to Sir Thomas!

But the wheel squeaks over-loud. ’Tis hardly wise

To advertise our presence. Stop awhile.

Hugh, stopping. But now no Lucy lurks to ambush us.

Will. Nay, but the trees have ears. A drop of piss …

Turning his back to the audience he tries to piss on the axle, but fails.

I leaked too lately and am quite dried up.

Soon shall I be replenished. Wait a space.

Hugh, chuckling. If Lucy is risen from judgment in his court,

Perchance he lurks in ambush at his house,

Looking to snatch more lovers of his lady

Ere the young harridan cuckold him more.

Will, also chuckling. I once a ballad made to the dunderhead.

Sings, to the tune of Dove’s Figary.

Sir Thomas was so covetous

To covet so much deer

When horns enough upon his head

Most plainly did appear.

Had not his worship one deer left?

What then? He had a wife

Took pains enough to find him horns

Should last him during life.

Hugh, laughing. A merry song! And now we have a deer

That once was his — and surely not his last —

Let us to Pidley and the pantry there

To leave the carcass, having cut a haunch

To dress your family table. And, that done,

I would you sit to have your portrait painted.

Will, astonished. My portrait painted? But by whom? And why?

Hugh, smiling. At Pidley sojourns a painter from Milan,

By name Figino, who is picturing

My father’s and my mother’s likenesses

Wherewith to decorate our gallery.

’Twere foolish of me to let slip the chance

Of yours likewise, to adorn my chamber wall.

Not large — a roundel — and not long to sit —

A simple draft limned lightly out in coal

Which he will tincture in the coming days.

Will you allow it?

Will, hesitantly. Never have I seen

An Italian. Is he an … earnest man?

Hugh, smiling. Nay, hardly earnest. Full of foreign graces,

He produces some extravagantly courteous gestures.

A fashion-monger, with his yellow hose

Cross-gartered, and with hats fantastical.

Will, smiling with anticipation. Then I’ll allow. And what shall follow on?

Hugh, hopefully. Before the day is out I deeply crave

To shoot an arrow in your butt once more,

Or more than once, and have you shoot in mine.

Will. I’d pass the whole long day in archery,

But not with safety at our house again.

This morn my father did close-question me —

The noises last night — were they made by me?

Why, yea, I said, and nay. There was a stir

When Lady Lucy had a (coughs) visitor

And her lord discovered them. So I arose

To view the happenings, hence the stealthy noise

My father heard. Not so far from the truth!

Tush, lad, he said, poke not your twitching nose

Into adulteries — you’re too young for such!

Hugh, he’s grown tetchy since his illness struck,

Suspicious too; we dare no more at home.

Welcome you are downstairs, but never up,

Welcome you are by daylight, not by dark —

Nocturnal visitors he equates with sin.

And sinned we have, in eyes of holy church,

Though not for me the sackcloth of remorse.

Hugh. Nor yet for me. Nor yet at Pidley Hall

Dare we to sin by morning, eve or dark.

But when we’re done with our Italian,

I know the very place for daylight sin.

Will. A moment yet. This wheel must silenced be.

By now perchance I am no longer dry.

Back to the audience, he pisses on the axle.

’Twill screech no more, and still a drop remains

To water wilting flowers.

He bestows the rest on two flowers growing on the verge.

Hugh. And what are they?

Will. The yellow, fleabane, a right sovereign herb

Which, dried and powdered, banishes fleas and lice —

A remedy for lousy Lucy fit.

The purple, monk’s hood, which dire poison yields.

It may with care be used when mixed with oil

As liniment against stiff aching joints.

But let it pass your lips, and you are dead.

Hugh. Then never let it pass your lips, or mine.

Will. Or even Lucy’s, mock him as we will.

We all are mortal, and we all do sin.

They move on. The wheel squeaks no more. Exeunt, singing Will’s ballad.

ACT III SCENE 2

A room in Pidley Hall. Figino is seated at a small easel. He has a goatee beard and a fantastical hat and his yellow stockings are cross-gartered. Enter Will nervously, carrying a bag containing the venison, and Hugh guiding him by the shoulder.

Hugh. Signor Figino, here is my friend Will

For you to picture with a speedy draft.

Figino. Sir, I am honoured!

He makes an elaborate bow which Will closely imitates in return. Figino fusses round Will, inspecting him from various angles.

Ah! The face of youth!

The face of spirit and of features rare!

Yes, in profilo, looking to the left.

Pray sir, here seat yourself and gaze to front,

And from your shoulder slip your collar down.

He continues to fuss until Will is arranged to his satisfaction, when he sits at his easel and sketches rapidly with his charcoal. Will, however, is fascinated by his hat and his stockings, and keeps staring at them.

Nay, sir, look not at me, but face ahead.

(To Hugh) Your succour, sir, will expedite my task.

Hugh stands behind Will, and whenever he moves his head out of position twists it back again.

Ah! That is better!

Will shows further signs of impatience.

Sir, I bear two names,

Benvolio Figino, and the first

Signifies “goodwill”. You being good, and Will,

Goodwill we share between us (titters). There! ’Tis done!

All I require now is liberty

To snip a sorrel curl from off your head

To give the hue exact.

He produces a pair of scissors and cuts off a curl.

I thank you, sirs.

Coloured it shall be by tomorrow night.

Will stands up and makes a Figino-style bow, which Figino returns.

Hugh, under his breath. Have you the meat? Then let us meet in sin.

Exeunt Will and Hugh, Will taking a lingering look at Figino’s stockings.

ACT III SCENE 3

Inside a barn. A large pile of hay is heaving from some invisible cause. From its depths erupts a resounding fart. Hugh’s head and naked shoulders emerge from the hay. He is gasping.

Hugh. The rankest goat were better than that blast!

Will bobs up beside him, grinning cheekily.

Will. ’Tis tit for tat. Into my bed you leapt

Reeking last night of Lady Lucy’s piss.

Hugh pretends to clip his ear. Noise off, and they dive down. Enter the farmer, sniffing.

Farmer. What were that thunder? What this windy whiff?

He sees movement in the hay and nods sagely.

Ah, be our Perkin tumbling with his lass.

Exit. Will and Hugh surface, grinning at each other. Laughter off. They submerge again. Enter Perkin and his girl, hand in hand. Will and Hugh howl like banshees, at which Perkin and girl flee in panic. Laughter from within the hay, which heaves once more.

Hugh, from the hay. Why tarry, Will? It is your turn to work.

Will, panting. Tarry? I work with all the speed I may.

Can you not feel the pleasure I bestow?

A loud bleat from within the hay. Hugh and Will resurface in alarm, peer down, and pull up a sheep by its horns. It bleats again. Will looks from the sheep to Hugh in wild surmise.

Will. Shaggy-arsed both, and readily mistook.

Hugh drops the sheep and pounces on Will.

ACT III SCENE 4

Church Street again. Enter the two watchmen holding Will, who is struggling. With them, Sir Thomas Lucy. They stop at the stocks.

Lucy. Lock him in fast.

Officer. But by whose warrant, sir?

Lucy. By mine. Am I not justice? Lock him in!

The watchmen hesitate but, under Lucy’s glare, obey.

Officer. For how long, sir?

Lucy. Until I give you word.

Exeunt, leaving Will sitting forlornly alone. Enter Hugh at a run, searching for Will.

Hugh. Will! What’s afoot? What knave confined you here?

Will. Lucy, who else? For cause inscrutable

Other than that he does not like my face

And that I witnessed yesternight his shame.

Hugh, he knows nothing of the deer we took —

He made no such insinuation —

’Tis but my visage sets him in a rage.

Home I went, as you know, to give the meat

Unto my mother. Leaving, he pinioned me

And bade the watch confine me in the stocks

With no charge laid, and no consenting voice.

So bring, I pray, another justice hither

Who in a trice may unknot this tangled web.

Hugh. I go. Wait here.

Will, plaintively. Wait? What else may I do?

Exit Hugh to the Guild Hall. While he is gone, Will experiments with his hands and feet. Shortly enter Hugh, Sir Thomas Lucy, another justice, and the watch.

Hugh, ranting. Alderman Shakespeare’s son, of tender

years,

Uncharged, untried, confined without a cause,

Sits here, the victim of Sir Thomas’ gall

And bent on claiming restitution.

Justice, to Lucy. And is this true? Why did you set him here?

Lucy gives no answer, but his face turns red.

Hugh, answering for him. One simple cause, as Martial did expound

—

Non amo te, Sabidi, nec possum dicere quare;

Hoc tantum possum dicere, non amo te.

The justice, pretending to understand, nods wisely.

Justice. Ah, those old Roman jurists ever had

A legal maxim fit for all events.

(To Lucy, aside) For yourself, sir, you have dug a pit profound

And, lest he sue for false imprisonment,

Methinks high recompense were not amiss.

(To Will) Would a sovereign satisfy your claim?

Will, with a show of reluctance. It would.

With the utmost ill grace Lucy hands the justice a sovereign and stumps off.

Justice, to the watch. Release him.

Will. Kind sir, thank you, but no need.

As the others gape, he frees himself. He is slender enough to pull his hands and feet through the holes. With a sweet smile he accepts the sovereign from the justice. Exeunt.

ACT III SCENE 5

The meadow by the Avon. Hugh and Will are lying on the grass.

Will. Tomorrow morn, my Hugh, the strolling players,

The men of my Lord Strange, do come to town.

First they attend the bailiff, whom they beg

For licence to perform and, if he grants,

In the Guild Hall they play their play before him

And all the worthies.

Hugh. And before us too?

Will. Why, yes. My father being alderman,

I may be there, and so, with me, may you.

And should the bailiff find no heresy

Or taint of treason, he allows them leave

For public show next day in a tavern yard.

But Hugh, do not you pin your hopes too high.

The fare they offer is but paltry stuff,

And surely you have better sustenance

At university.

Hugh. What, proper plays?

As Seneca or Roman comedies

Arranged and ordered into acts and scenes?

Why yes, we do, but most are full of wind —

As are your bowels — or are gibberish.

Will. Few even of that kind are tasted here.

Horseplay the diet of these wandering troops —

Clowning and tumbling — and the pleasureless

Sermons of obsolete moralities.

Hugh, I desire myself to write a play,

A proper play, on Plautus or Terence framed,

A play full not of wind or gibberish

But solid substance and high poetry.

Tragical, comic or historical,

I know not yet. Yea, all of those, one day,

But somewhere must I start and make attempt.

And when I’m older I’ll to London go,

That teeming centre of experiment,

And write in earnest. London a theatre has,

No puny platform clapped up for the nonce

In the Guild Hall of some poor pelting town,

But a full theatre to the purpose built —

On such a stage shall I present my plays.

Hugh. Strength to your arm! But what pattern do you have

On which to model compositions?

Will. On mother wit! But I accept your drift —

I want examples. Wherefore I propose

To beard the leader of my Lord Strange’s Men

And buy or borrow his unwanted stock

Of plays, to serve as touchstones for the gold

Which I transmute.

Hugh. Gold shall it surely be.

But till you hold that metal in your hand,

May I help you pay for books?

Will, hefting his purse. You do forget

The purse which flew to me from heaven above

And today’s sovereign.

Hugh. I do not forget.

But I too have a purse at your command.

Will smiles in gratitude. Curtain.

ACT IV SCENE 1

Church Street. People are assembling, among them Will and Hugh. Distant music of cornett, pipe and drum, drawing closer. Enter the players, some playing instruments and some, in harlequin garb, jigging and turning cartwheels. Will approaches the leading musician who, seeing that he wishes to speak, silences the music.

Symons. Young master, may John Symons be of service?

Will. Pray tell me, sir, what you’re about to play.

Symons, oleaginously. An interlude, The Seven Deadly Sins

—

That most improving and right moral tale —

Enlivened with diverse activities —

A gallimaufry glut of gambolling!

Will. No play, then? No full play?

Symons. Alas, sir, no.

Good people here applaud not lengthy plays,

Nor pay to see them. We must needs supply

What they demand. No more full plays we’ll do.

Will. Have you then play-books which I might acquire?

Symons, considering. I think I have four old and solid plays.

How much for all of them?

Will, chinking his purse. Two shillings.

Symons, slapping Will’s hand. Done!

Meet here, young sir, when the performance ends,

And they shall be in your possession.

The players strike up and move off, followed by the rest of the crowd. The lights go off to indicate the passage of time. Sounds of applause. Re-enter Symons, bowing obsequiously to the worthies now leaving the Guild Hall. Re-enter Hugh and Will.

Will, grumbling. Oh Stratford burghers unsophisticate!

A fig, I say, for The Seven Deadly Sins!

May heaven protect us from its vanities —

“Forfend the fearful fiend that frights with fangs of flaming fire

And darting down the darksome dale dispenses danger dire” —

Oh Stratford, that you should endure such trash!

Symons beckons him, hands over four slim unbound quartos, and Will gives him some coins. Will rejoins Hugh.

Will. Alone now let us study these our spoils.

Exeunt.

ACT IV SCENE 2

The garden of the Shakespeare house. Flower beds behind. Hugh and Will lie on the grass, eating bread and cheese and drinking beer from a flagon. Will is reading a book and mumbles, his mouth full. Hugh removes the book from his hand, waits until he has swallowed, and gives it back.

Will. Ralph Roister Doister here, a comedy. This in the prologue — would the rest were better — “Our comedy or interlude which we intend to play. Is named Roister Doister indeed. Which against the vainglorious doth inveigh, Whose humour the roisting sort continually doth feed. Thus by your patience we intend to proceed In this our interlude by God’s leave and grace, And here I take my leave for a certain space.” No roistering there! Nothing but flatulence!

He swigs from the flagon.

Hugh. Agreed. Expel it.

Will belches. Hugh picks up another book.

Ah! but here is one

I know and love well, Gammer Gurton’s Needle,

Writ by a Christ’s man, William Stevenson,

And still performed there to our great delight —

“My Gammer sat her down on her cushion and bad me reach thy breeches,

And by and by — a vengeance on it! — or she take two stitches

To clap a patch upon thine arse, by chance aside she leers,

And Gib, our cat, in the milk pan she spied, over head and ears.

‘Ah, whore! Out, thief!’ she cried aloud, and slapped the breeches down;

Up went her staff and out leapt Gib at doors into the town.”

Will, laughing. A play of little things, a play of promise.

There may be matter there for pondering.

Set it aside. I’ll read it through.

He picks up a third book.

Oh heaven!

“A lamentable tragedy mixed full of pleasant mirth, containing the life of Cambyses

King of Persia, from the beginning of his kingdom unto his death, his one good deed of

execution, after that many wicked deeds and tyrannous murders committed by and through him, and

last of all his odious death by God’s justice appointed.”

(Dubiously) Dare we adventure into this land?

Hugh. Try.

Will, reading. “My Council grave and sapient, with lords

of legal train,

Attentive ears towards me bend, and mark what shall be sain;

So you likewise, my valiant knight, whose manly acts doth fly

By brute of Fame, that sounding trump doth pierce the azure sky.

(Groans)

My sapient words, I say, perpend, and so your skill delate!

You know that Mors vanquishèd hath Cyrus, that king of state,

And I, by due inheritance, possess that princely crown,

Ruling by sword of mighty force in place of great renown.”

— Bombast and fustian! To be cast away!

Hugh picks up the last book.

Hugh. And here the tragedy of Gorboduc —

“My lords whose grave advice and faithful aid

Have long upheld my honour and my Realm

And brought me to this age from tender years,

Guiding so great estate with great renown.

(Gabbles ever faster) Now

more importeth me the erst to use

Your faith and wisdom whereby yet I reign,

That when by death my life and rule shall cease,

The kingdom yet may with unbroken course …”

— So on, and on, and on, with unbroken course.

Will. A tragedy, you say? Tragedy it were writ.

It hangs as heavy as when parsons preach,

In matter irksome and in phrases flat.

But the metre offers promise. All iambs —

Di dum di dum di dum di dum di dum.

Were that but looser, less reiterant

And ofter over-running line to line,

’Twould plod the less and skip more spirited.

This above all, it is not fettered down

By hampering chains of couplet and of rhyme.

Hugh. Blank verse they call it. It is somewhat new.

I read a version of the Aeneid

Done by my Lord of Surrey. Aeneas,

Warned by a god, if I remember well,

Determines thus his Dido to forsake —

“Aeneas, of this sudden vision

Adread, starts up out of his sleep in haste;

Calls up his feres: ‘Awake, get up, my men,

Aboard your ships, and hoist up sail with speed;

A god me wills, sent from above again,

To haste my flight, and wreathen cables cut’.”

Will. Hugh, there you have it! Blank verse, be it free

And tempered to the tone of him who speaks,

May suit the nature of all characters —

The speech of mighty monarchs, matters of state

And high resounding phrases on their lips —

Or of laconic soldiers, helmed and spurred,

Marshalling ranks, defiant of the foe —

Or of the seeker after truths profound,

Soliloquising his philosophies —

Or tragic lovers foiled of their intent

By unrespited grudge of destiny —

Or bumbling clowns and bibblers in their cups

Bawling obscenity across the ale —

Or humble folk like us, like me, who speak

Of ordinary deeds of small account,

Of homely things that happen every day.

Hugh. So, having found your metre, what your theme?

Will. A homely history first, of Hugh and Will

And all their doings since they first did meet

And love and be their little foolish selves;

A truthful tale without embroidery,

Without excision and without excuse.

Not to be acted on a public stage —

Oh no! — two copies only, thine and mine,

Close to be cherished in our secret hoard

And never to be seen by other eye,

So that, when old and grey, we may look back

And may remember with advantages

How one time we did love. But when this task

Is over, I’ll more weighty themes address

And open up a sampler of the world.

O god of theatre! May you with wit inspire

This dabbling scribbler, puppy playmonger,

To abjure dull sermons and cheap clownish tricks

And discover that which is, or which may be;

That all who see may see themselves alive,

A mirror of their own inconstancies;

That all who hear may hear themselves aloud,

An echo of their own desires and hopes,

Their fears and angers, malices, despairs,

And their own laughters. God but grant me this!

Hugh. And so he shall! But are there actors there

Skilful enough such qualities to portray?

Will. If not, then I must play them all myself.

Hugh laughs, then pauses for thought.

Hugh. Will … of your first play I must have my copy,

Hid, as you say, deep in my secret hoard,

Perused by me alone. And rightly so,

For our closest deeds, unexcised, unexcused,

If loosed abroad would all too ready prove

Tinder to spark. What hoards are truly safe?

At home, my parents are inquisitive,

And he with whom I share my Cambridge room

Is bloated up with righteous purity —

I dare not risk them setting eyes on it.

Will. What if the words were hidden and disguised?

Letter by letter pricked in a printed book

Itself beyond reproach — a bible, say?

Harder by far to read than if writ plain,

But not so hard as cipher. Would that serve?

Hugh. Yea, ’twould be safe enough from prying eyes.

So be it … Meantime, Will, one question more —

What is to be the title of your play?

Will. I have not thought. What think you it should be?

Hugh thinks. Meanwhile Will idly investigates flowers in the bed behind. Hugh mutters occasional words and shakes his head.

Hugh. Suggestion fails me. Leave it. It will come.

Will plucks a red rose and sticks it in Hugh’s doublet.

Will. Till then, a rose for passion. Not a bud —

We’re well bepricked, and not too young to love.

Hugh, sniffing. It smells more sweet than you … when you

break wind.

Roses I know, but to my shame as few

Flowers of garden can I call by name

As flowers of meadow. Therefore teach me more.

Will, impatiently. What’s in a name? That which we call a

rose

By any other name would smell as sweet …

(To himself) A happy phrasing, not to be forgot!

Hugh. But I would hear their names, so do you tell.

Forget-me-not, yes … lupin … hollyhock …

He points to a flower.

But how are these tall golden buttons known?

Will. As tansy. Bitter to eat. They purge the worms.

Hugh points to another flower.

Hugh. And this tight-clustered bloom of blushful hue?

Will, grinning. Of blushful Hugh?

Both laugh.

It is Sweet William.

Hugh. Why, there you have it, plain as plain may be!

The title of your play! Sweet William!

Will. Yea! Yet the matter is not Will alone

But also Hugh. Wherefore some further words

Should celebrate Hugh’s bloom of lustihood.

Call it Sweet William and Blushful Hugh!

Hugh. No, no! You are the pith, the core, the heart,

And I would not in blushful mortal guise

Be made immortal. You it is should blush.

Sweet William let it be. It is enough,

As is sweet William himself enough …

And yet of him I ne’er can have enough.

He looks to see if anyone is watching, kisses Will, and adjusts himself.

Methinks the hay-barn beckons us to more.

Exeunt.

ACT IV SCENE 3

The parlour in the Shakespeare house, by night. Will is sitting at a table, writing by the light of two candles which are almost burnt down. On the table is a thick book. From time to time he looks into infinity for inspiration. After a while he lays down his quill and stretches.

Will. Enough for now! ’Tis well in hand. The tale,

More freely flowing than I dared to hope,

Advances well-nigh to the present time.

(Yawning) Tomorrow night I’ll prick it in the bible.

He pats the book, and blows out the candles. Curtain.

ACT V SCENE 1

Church Street. People are passing by, including Will and Hugh. Hugh is ogling a pretty girl and Will slaps him on the wrist.

Will. Avert your eyes! It is with me you sin!

Enter two boys at a run, each carrying a dead rabbit, and hide among the bystanders. Enter Sir Thomas Lucy in hot pursuit.

Lucy, panting. Hold them! Despoilers of my private lands!

Robbers of warrens! Shameless plunderers!

(Pointing at Will) And hold him! Author of disturbances!

Nobody moves. Lucy lunges and grabs Will’s breeches, which he yanks. The breeches tear in half. Will yelps and covers himself with his hands. Enter the two men of the watch. Lucy, appalled, pulls his hood over his head. The poacher boys melt away. Hugh points at Lucy.

Hugh. Constables, seize this man! He did pursue

Two boys, accusing them of stealing game,

The rights and wrongs of which I do not know.

But rather than apprehend them as he should,

He tore the breeches off my young friend here,

And wantonly exposed his privities

To public gaze, against all decency.

This lad is innocent of felony.

All day he’s been with me, within my sight,

As I will vouch before the justices.

Officer, taking hold of Lucy. Come along, you. Answer to the

justices.

(To Hugh and Will) And you, sirs, likewise come to testify.

They frogmarch Lucy off, still hooded. The bystanders applaud. Will and Hugh follow, Will covering his embarrassment with his cloak held like a skirt. He minces, and Hugh cuffs him.

ACT V SCENE 2

The same, half an hour later. Hugh is among the bystanders. Enter Will in haste.

Will, to Hugh. These my best breeches. Mother scolded me

For tearing the others, and was deep amazed

To learn that I would pay her for the loss.

He looks around.

Not here yet? Soon they’ll come. Hugh, to the market,

And bring some rotten fruit.

Hugh runs off. Will addresses the audience.

Well, what a jest!

Lucy, behooded, stands before the court;

When asked his name he mumbles in his beard;

“Unhood him, watch!” they cry, and jaws drop down.

The watch recount his crime, and Hugh and I

Attest the truth. “How then, sir, do you plead?”

“Guilty, your honours.” Item, he is condemned

To sit in stocks six hours, on market day!

Item, for that he did unveil my yard,

To pay to me a golden sovereign!

Item, to buy new breeches, shillings five —

The old were worn and thin, worth bare a groat!

Item, he is deprived of justiceship,

His wand of office broke before his eyes!

Music is heard. Hugh returns with two large baskets, which he sets down.

Hugh. The players come, to gambol at the tavern.

Will. Aha! With them we may improve the jest!

Enter the players. Will, holding up a coin, accosts John Symons.

Pray, Master Symons, may I your service beg

For a brief moment? Soon will come this way

A malefactor to the stocks condemned.

I would your good self and your company

Escort him, as if to the gallows bound,

With tragi-comic retinue before

And solemn drum-beat and funereal dirge,

And when he’s pent, deride him cuckoldly

With frumpery and rustic capering.

Symons, taking the coin. A modest task. We can, and so we will.

Will, pointing off. But there they come, prisoner and guard alike.

The players leave. Re-enter first the musicians playing mournful music and then the clowns slow-marching, followed by the watch with a woebegone Lucy whom they lock in the stocks. The players switch to lively tunes and caper round him, bleating like goats. Exeunt players. The crowd pelts Lucy with fruit and vegetables. Hugh makes to join in, but Will, who has been watching with growing concern, puts a restraining hand on his arm. Lucy observes this.

Lucy, between his teeth. Throw, dandiprat, throw! Come, wreak your dear revenge!

Will shakes his head, and pulls Hugh to the front of the stage.

Hugh. Will, why so loath to vaunt your victory?

Will. My victory I’ve already crowed enough

And would not wish to counter spite with spite

Lest he return and counter it with more.

Victim is Lucy now. I pity him,

And do repent the players’ mockery.

Lesson he’s learned, if I compassion show

And now forbear to aggravate the smart.

He turns to Lucy and bows, hands spread, signifying an end to hostilities.

Hugh, shrugging. Well, such forbearance I can only praise.

This, though, the conclusion of his sorry tale.

Will, sighing. And near conclusion of our merry tale.

Next week I’ll be a dusty attorney’s drudge,

Tomorrow you shall be upon the road

To Cambridge, each out of the other’s life.

Hugh. But not the other’s thoughts. And still we have

An hour or two to spend of our today.

Will. An hour or two to frolic in the hay!

Exeunt.

ACT V SCENE 3

The parlour in the Shakespeare house. Will is sitting at the table pricking the play into the bible. A knock at the door, and enter Hugh dressed for riding. A certain constraint is apparent between them, Hugh unwilling to linger and Will to detain him, as if both know that a chapter has been closed. Hugh inspects what Will has been doing.

Hugh. The play’s afoot! And how far have you reached?

Will, looking. The second chapter of Leviticus.

Hugh. No, doddipoll! How far into the play?

Will. It all is writ, except this final scene

Which can not be completed till you’re gone.

But two acts only of the five are pricked.

Hugh. Therefore I can not take it with me now?

Will. No. Pricking is irksome toil. It will be

Another day or more or it is done.

But when the final jot is entered in,

Myself to Pidley I’ll deliver it