Indelicate Frivolities

3. Gammer Gurton’s Inglecock

“What the hell,” I asked, “is an inglecock?”

I was sitting at a table in the great hall of a ramshackle Tudor house in the depths of Hampshire. In front of me were a laptop, a paperback, several pages of my own notes, and a sheaf of ancient paper covered with abominable sixteenth-century handwriting. Behind me were Alex and Hugo, staring helplessly at the words on the screen.

“It sounds like a sort of bellows,” said Alex. “But how do I get it up my arse?”

What we were talking about is going to take quite a bit of explaining. But here goes.

*

Old Persimmon had given Hugo the task of producing Hambledon School’s next renaissance play. But this time round there were two departures from the norm. Rather than the producer being named in July and the play performed in March, he was appointed in March for a performance in December. And instead of Hugo having a free hand in choosing his play, Old Persimmon positively begged him to do Gammer Gurton’s Needle. For both these there were very good reasons.

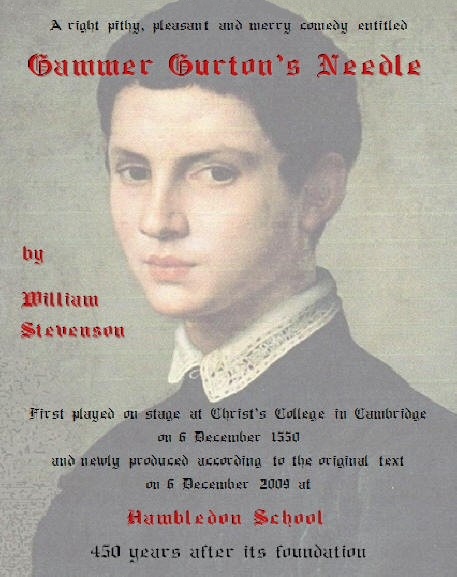

The school had been founded in 1559, and it was now 2009 and the 450th anniversary. The main celebrations were taking place in the summer, but a grand finale was wanted at the end of the year. And the Founder had been a certain William Stevenson, whose other claim to fame was the authorship — not categorically proved but generally accepted — of Gammer Gurton’s Needle, which is one of the two earliest comedies in English. What better than to wind up the festivities with the Founder’s own play?

As you’ll have gathered by now, I’m a bit of a geek. I’m a fan of Elizabethan theatre and, like anyone who’s really into it, I had picked up quite a lot about the traditions from which it grew. So I had already read Gammer Gurton. But Hugo hadn’t, nor had anybody else I knew apart from Old Persimmon. Hugo’s first move was to discover how many actors were needed. Then he bought enough copies of the New Mermaid edition which Old Persimmon recommended. Then he asked a number of boys — me included — to take part, though our roles were yet to be decided. Finally he asked Rob to brood on possible designs for the set. So off we all went with our copies to read over the Easter holidays.

For the first few days I was staying with Rob (whose parents, unlike mine, had no problems with us being gay and teamed up) and together we sat down to Gammer Gurton. It’s a short affair — only 1,280 lines, quite a bit less than any Shakespeare play — and it’s in rhyming couplets. Though earlier than Shakespeare and spattered with a fair number of obsolete words, it’s no harder to understand, and our edition had helpful notes. And above all it’s fun — an earthy, racy, rollicking farce with plenty of scope for slapstick; good material, come to think of it, for the Marx Brothers if the film censors hadn’t been around.

We looked at a reproduction of the title page of the first edition. A Ryght Pithy, Pleasaunt and merie Comedie: Intytuled Gammer Gurtons Nedle Played on Stage, not long ago in Christes Colledge in Cambridge. Made by Mr. S. Master of Art. Imprented at London in Fleetestreat beneth the Conduit at the signe of S. John Evangelist by Thomas Colwell.

“Date?” asked Rob.

“Published 1575. It says so at the end. But written and acted a good twenty years earlier.”

“Who’s who, then? Ah, here’s the list of characters. Gammer Gurton. Gammer?”

“Old woman. Short for grandmother. Like gaffer’s short for grandfather.”

“Right. Hodge, Gammer’s servant. How old?”

“Youngish. Twenties.”

“Tib, Gammer’s maid. Young too?”

“Yes.”

“Cock, Gammer’s boy. Nice name. Boy meaning son?”

“No, another servant. Houseboy.”

“Diccon, the Bedlam?”

“Bedlamite. An ex-inmate of Bedlam the madhouse, licensed to beg. Or at least claiming to be. Anyway, a beggar. But he’s far from mad, just a mischief-maker. Living off his wits.”

“Ah. Dame Chat?”

“Friend of Gammer’s. Runs a pub next door.”

“Doctor Rat, the vicar?”

“Grumpy. Pompous. Dim-witted. Fat. Likes his beer.”

“Master Bailey?”

“Means bailiff. The sheriff’s officer, representing law and order, who sorts everything out.”

“Doll, Chat’s maid? And Scapethrift, Bailey’s servant?”

“Mutes. Not speaking parts.”

“And Gib, Gammer’s cat. Presumably doesn’t speak either?”

“No, but I expect Hugo’ll want cat noises. We can hardly have a real moggy. Couldn’t control it. So he’ll probably get you to lay on a dummy one.”

“Hmm. That’s the lot, then. What’s the setting?”

“A village street. Behind it, Gammer’s house and Chat’s pub. Just their fronts — you don’t see inside. Each with a door. An upstairs window in Gammer’s. No changes of scene.”

“Sounds simple enough. Nicely rustic. And no fancy costumes?”

“No. Gammer and her household are yokels. But everything hinges on Hodge’s leather trousers — two pairs, both with holes in the seat — and he shits in one of them. All of that lot speak in dialect, by the way — ich for I, like in German; cham, I am; chold, I would. That sort of thing. If Hugo’s wise he’ll modernise it a bit. Chat and Rat and Bailey are higher up the social scale. Better dress for them, and no dialect.”

“OK. And what’s the plot?

“Read the Prologue. It gives the whole game away.”

When quoting, I’ll modernise the obscurer words, or add an explanation if they have to stay for the sake of the rhyme.

As Gammer Gurton, with many a wide stitch,

Sat piecing and patching of Hodge her man’s breech,

By chance or misfortune as she her gear tossed,

In Hodge’s leather breeches her needle she lost.

When Diccon the Bedlam had heard by report

That good Gammer Gurton was robbed in this sort,

He quietly persuaded with her in that stound [at that time]

Dame Chat, her dear gossip, this needle had found;

Yet knew she no more of this matter, alas,

Than knoweth Tom our clerk what the priest saith at mass.

Hereof there ensued so fearful a fray,

Mas’ Doctor was sent for, these gossips to stay,

Because he was curate and esteemed full wise;

Who found that he sought not, by Diccon’s device.

When all things were tumbled and clean out of fashion [in utter

chaos],

Whether it were by fortune or some other constellation [planetary

arrangement],

Suddenly the needle Hodge found by the pricking

And drew it out of his buttock where he felt it sticking,

Their hearts then at rest with perfect security,

With a pot of good ale they struck up their plaudite [applause].

Rob laughed. “So they spend the whole play just looking for a needle?”

“More or less. But with complications. Let’s read it through.”

So we read, with comments from time to time.

Diccon wanders into the village and hears unaccountable wailing from Gammer’s household. He takes advantage of their distraction by nicking a joint of bacon from inside the door. Hodge, unaware of the disaster that has struck, arrives home from digging in the field. He’s grumbling about the state of his trousers — filthy, and with a great hole in the seat — and hoping that Gammer’s mended his other pair. He’s also grumbling about the work that Gammer puts him to.

“I would she had the squirt!” read Rob. “The footnote says the squirt is the trots!”

“It’s littered with that sort of thing. Look, down here — they gave no more heed to my talk than thou wouldst to a turd. The whole thing’s what the Victorians would call vulgar.”

Tib comes out of the house and tells Hodge what’s happened.

My Gammer sat her down on her cushion and bad me reach thy breeches,

And by and by — a vengeance on it! — or she take two stitches

To clap a patch upon thine arse, by chance aside she leers,

And Gib, our cat, in the milk pan she spied, over head and ears.

‘Ah, whore! Out, thief!’ she cried aloud, and slapped the breeches down;

Up went her staff and out leapt Gib at doors into the town.

But Gammer’s needle — her only needle, an item of considerable value in those days — has disappeared, and despite endless searching it can’t be found. Hodge, upset that his other breeches are still unmended, demands a candle so that he can search in the murky house for himself. Gammer tells Cock to light one at the hearth, but he takes an unduly long time.

Hodge: Come away, ye whoreson boy! Are ye asleep? Ye must have a crier!

Cock [within]: I cannot get the candle light — here is almost no fire.

Hodge: I’ll hold thee a penny I’ll make ye come if that I may catch

thine ears!

Art deaf, thou whoreson boy? Cock, I say! Why, canst thou not hear us?

Gammer: Beat him not, Hodge, but help the boy and come you two together.

“Is it just my dirty mind?” asked Rob. “I’ll make ye come! All those comes, in fact.”

“Mine’s dirty too. The whole play’s full of puns and innuendos, you know, like pricks in bums. Innocent enough on the face of it. But give them a bit of emphasis, or the odd wink …”

Cock comes out (see? — you’re reading things into it too!) and Hodge goes in to light the candle. Cock, looking in through the door, describes how Hodge is trying to blow up sparks in the fire. But the sparks are really the eyes of Gib the cat, shining in the dark. Gib, who doesn’t like being puffed at, dashes screeching upstairs followed by a cursing Hodge who shouts for help from the window because — he thinks — Gib’s tail is on fire and in danger of setting the thatch alight. Gammer calls him down, tells him not to be an idiot, and makes them all have yet another look. That gives rise to false alarms.

Cock: By my troth, Gammer, methought your needle here I saw,

But when my fingers touched it, I felt it was a straw.

Tib: See, Hodge, what’s this? May it not be within it?

Hodge: Break it, fool, with thy hand, and see and thou canst find it.

Tib: Nay, break it you, Hodge, according to your word.

Hodge: God’s sides! Fie, it stinks! It is a cat’s turd! It were well done to make thee eat it, by the mass!

“Eat it?” cried Rob.

“It’s poking fun at the catholic mass. This is a protestant play, remember. It pokes plenty of fun at catholic saints too.”

Act II. The sound of a drinking song wafts out from the pub. Diccon and Hodge enter. Hodge, lamenting his lack of decent trousers, explains the loss of Gammer’s needle. Diccon thinks he said ‘Gammer’s eel’.

Hodge: Tush, tush, her nee’le, her nee’le, her nee’le, man

— ’tis neither flesh nor fish!

A little thing with a hole in the end, as bright as any silver,

Small, long, sharp at the point, and straight as any pillar.

“More innuendo,” I said. “In those days, needle also meant a cock.”

But why, asks Diccon, is Hodge so keen to get his trousers mended? Because, says Hodge,

Kirstian Clack, Tom Simson’s maid, by the mass, comes hither tomorrow.

I’m not able to say between us what may hap;

She smiled on me the last Sunday, when I put off my cap.

Ah, says Diccon, that is important. Look, can you keep a secret? Then swear it by kissing my arse; which Diccon reluctantly does. To get the needle back, Diccon goes on, I’ll have to summon up the devil. And, with appropriate mumbo-jumbo, he pretends to do so. Silly Hodge, terrified, finds his bowels turning to water.

By the mass, I’m able no longer to hold it!

Too bad — I must befoul the hall!

Diccon: Stand to it, Hodge! Stir not, you whoreson!

What devil, be thine arse-strings bursten?

But Hodge, already crapping in his pants, has run indoors. “Fie, shitten knave!” cries Diccon, and goes next door to call on Dame Chat. He tells her, quite falsely, that Gammer Gurton thinks Chat has stolen her cock.

“Of course,” I pointed out, “he means her rooster. But you’ve got to remember that all these parts were played by men or boys. Exactly like us. And the whole of the play’s littered with cocks. The stolen cock crops up time and again. So does Cock the boy. So does cox, meaning fool. Hint, hint, nudge, wink.”

And when Hodge ventures out again, having changed his breeches for the ones Gammer has been mending, Diccon tells him, equally falsely, that Chat has stolen Gammer’s needle; and Hodge passes the message on to Gammer.

Musical interlude. Act III. Gammer and Chat emerge at cross purposes, trade exceedingly rude words, and fall to fisticuffs. Hodge and Cock look on, crying encouragement but doing nothing to help. Gammer, having had the worst of it, sends Cock to fetch Doctor Rat to see justice done. Meanwhile Gib the cat is ailing, and Hodge, suspecting she has swallowed the needle, has to be dissuaded from raking out her arse to find it.

Interlude. Act IV. When the vicar arrives, dragged grumbling out of another pub, Hodge explains everything as far as he understands it. They all go into Gammer’s house to talk it over, except for Diccon who calls on Chat again and tells her that Hodge is about to steal her hens by breaking into her house through a hole in the wall. Chat goes indoors to await him, and Diccon tells Rat, when he comes out, that he has just seen Chat sewing with Gammer’s needle. If Rat crawls through that hole he’ll witness it with his own eyes. And so the credulous Rat does. When halfway in, his bum sticking out, he yelps that he’s been bashed on the head, and emerges backwards with a bloody pate.

“That ought all to be visible,” Rob said thoughtfully. “Not his head — the make-up chap needs to slap blood on it while he’s in the hole. Just his fat bum — nice opportunity for a good loud fart. Right, so the hole’s got to be in Chat’s front wall.”

Rat goes off in dudgeon to fetch Master Bailey to conduct an inquiry.

Interlude. Act V. They arrive together. Rat, his head now in bandages, is complaining bitterly. Bailey points out that, as a self-confessed burglar, he got what he deserved.

By my troth, and well worthy, besides, to kiss the stocks.

To come in by the back side when ye might go about!

He calls out Dame Chat, who still thinks it was Hodge that she brained. She demands that Gammer and Hodge be questioned too. But Hodge denies burglary, and his head is uninjured. Gammer resurrects the accusation that Chat has stolen her needle, and Chat resents the rankling accusation that she has stolen Gammer’s cock. This brings Bailey to the point. Who, he asks, first made these accusations? The answer to both is Diccon. He is summoned and, after much prevaricating, admits everything. Though Rat wants him hanged, Bailey merely orders him to promise to make amends to everyone he has wronged — Rat, Chat, Gammer, Hodge, even Gib — and to seal the promise by swearing an oath on the seat of Hodge’s leather breeches. Diccon agrees.

But Hodge, he insists, take good heed now thou do not beshite me!

[Gives him a good blow on the buttock]

Hodge: God’s heart, thou false villain, dost thou bite me?

Bailey: What, Hodge, doth he hurt thee or ever he begin?

Hodge: He thrust me into the buttock with a bodkin or a pin!

I say, Gammer! Gammer! … I have it, by the mass, Gammer!

Gammer: What? Not my needle, Hodge!

And there of course it is, in the seat of Hodge’s breeches all the time, and now pricking him deep in his bum. More innuendo here, naturally — a needle (also meaning a cock) in his arse. He extracts it, and amid general rejoicing everyone repairs to Chat’s pub for a drink.

“Well, that’s fun,” was Rob’s verdict. “More fun than I expected. And I’ve got some ideas for the set. Half-timbered houses, don’t you think? Let me do some sketching before I forget.”

While he sketched, I read the editor’s introduction. It was good, but it left me with an uneasy feeling that there was something I didn’t quite go along with. That led me into lengthy but inconclusive searches on the web, until Rob interrupted to show me his preliminary design.

“They wouldn’t have had much scenery and stuff, would they?” he asked. “Not originally?”

“Not much. There weren’t any theatres at all. Not then, not public ones. Only private, with a temporary stage rigged up in the dining hall at Oxford and Cambridge colleges — like Gammer — or at schools like St Paul’s and Eton, or royal palaces, or the guildhall in provincial towns.”

“Who were the actors, then?”

“Either troupes who wandered round the country playing medieval morality plays, hideously serious and dull, spiced up with interludes of music and clowning. Or else amateurs putting on their own plays in schools and colleges and suchlike. In places like that, you see, they’d begun to revive Latin drama — Plautus’ and Terence’s comedies, Seneca’s tragedies — and they even put on new plays in English that were based on classical models, complete with acts and scenes to give them structure.”

“So Gammer’s one of those?”

“That’s right. We’ve got two English comedies from the 1550s. The first was Ralph Roister Doister, which was written by a certain Nicholas Udall. He was headmaster of Eton.” I chuckled. “Or rather he had been, until he was sacked for buggering his boys. But he got a year’s salary as severance pay, and didn’t spend long in jug. And he ended up as headmaster of Westminster School.”

“He got off lightly!”

“He did. Under the Buggery Act he could’ve been hanged. But in Tudor times, whatever the law said, they weren’t much bothered about what you did in bed, unless it resulted in public scandal. I think only one person was hanged for it — Lord Hungerford, who’d buggered half his servants. And what really scuppered him was heresy and astrology — forecasting the death of the king. Much worse crimes. The buggery was just an add-on. Where were we?”

“Ralph something-or-other.”

“Oh yes. Well, that’s based on Plautus and Terence but with an English slant to it, and it’s pretty decorous. Gammer Gurton’s much more original. They always say it came after Roister Doister” — my vague unease returned — “and there’s hardly anything classical about it. Then in 1561 someone wrote a tragedy called Gorboduc. Monumentally boring, but it’s the first play in blank verse. Stumping and wooden, sure, but it’s the medium that Marlowe and Shakespeare transformed into poetry … Sorry, I’m being geeky. I’m lecturing.” I was all too liable to lecture when I got on my hobby horse.

“So what?” said Rob. “I like you being geeky. I like you lecturing.”

“Oh. Good.” We were becoming less rude with each other all the time. It must be love at work. “Anyway, it was only in 1576 that the first theatre was built in London. The shows were getting a bit more sophisticated by now, but they were still tedious or inarticulate or even nonsense. Until 1587, when a young man arrived in London from Cambridge with a new play in his pocket. His name was Christopher Marlowe, and his play was Tamburlaine. It was put on at the Rose. Some of it’s noise and bombast, but the rest’s pure poetry — thundering blank verse of a kind that had never been heard before. Marlowe knew exactly what he was up to. The prologue begins

“From jigging veins of rhyming mother-wits,

And such conceits as clownage keeps in pay,

“— there’s Gammer for you, or the play the mechanicals put on in the Dream —

“We’ll lead you to the stately tent of war,

Where you shall hear the Scythian Tamburlaine

Threatening the world with high astounding terms.”

I paused in wonderment. Tamburlaine never ceases to enslave me. “It was the biggest revolution in the history of English theatre. It was the spark which set the stage alight. The audience must’ve gone home reeling. Every playwright in London would’ve been there, and they all jumped on the bandwagon. Shakespeare included. He’d just arrived from Stratford, and there and then he sat down to write his first play. Parts of Henry VI are pure Marlowe — he must have seen Tamburlaine. And the rest, as they say, is history.”

“Good God!” said Rob. “I never knew that. But Gammer was a good step along the path?”

“Oh yes. It came thirty-odd years before Tamburlaine, and in its simple way it was mould-breaking too.”

At that point we were called down to dinner.

In bed that night I said, “Thank you, Rob.”

His only reply was to hug me. He knew what I was thanking him for.

*

After a few days I returned to my dysfunctional home. I eased the boredom by further thinking and further searching, and managed to pinpoint the source of my unease about Gammer’s date. Another fortnight and I was back at Hambledon, where Hugo called everyone together for a meeting.

“Now we’ve all read it,” he said, “we’ve got to decide who plays who. It’s just the eight of us. The Lovibond lasses won’t be here, and we don’t need any tiddlers. For starters, I’ve put myself down for Hodge and Sam for Diccon. And Sam, you’d better do the prologue too.”

He gave Gammer and Chat (“they’re really pantomime dames who don’t need unbroken voices”) and Rat and Bailey to boys who’d also been in the Dream.

“Are you all happy with those?”

We were. Myself, I was very happy, because Diccon is a great part. And that left, of the actors present, only young Matt Brown who’d been Helena in the Dream, and Alex Stevenson who’d not only been Hermia but also, the year before, the young prince in my Edward II.

“Then the question,” said Hugo, “is whether Alex does Cock and Matt does Tib, or the other way round. For Tib we need an unbroken voice, but for Cock it doesn’t matter. Matt, d’you think your voice is going to break before December?”

“No idea.”

“Well, if you don’t mind me being personal, have you got any hair down there?”

“Um, no.”

“Alex?”

“Yes, I have. Quite a bit. I think my voice’ll go soon. High time too. And a good thing if it does, seeing what I’ve let myself in for on Speech Day.”

Someone asked what he meant.

“Oh, didn’t you know? The Founder was an ancestor of mine, you see. Stevensons have been coming to Hambledon ever since it started. And because my grandpa and my dad are both dead, I’m the current Stevenson, and the headmaster’s lined me up to say a few words on Speech Day. I’d much rather do that without squeaking.”

“And it’s great,” said Hugo, “that you’re in your ancestor’s play. I got a hell of a kick from playing my own ancestor in Edward II. Right then, it looks like Cock for Alex and Tib for Matt. OK? ”

He went on to talk about the play, and I was impressed. He seemed a maturer Hugo, taking his job with proper seriousness — while firmly insisting that Gammer had to be fun — and everything he said made very good sense. He was going to liaise with the director of music over suitable music for the interludes. He passed round Rob’s preliminary sketches for the set and invited comments. He ended by pointing out that while Gammer was quite popular with amateur dramatic groups, they always used heavily sanitised versions. Very rarely was it performed uncensored.

“We’ve got to modernise some of the dialect that’s simply too difficult. But otherwise we’re doing it complete and unabridged, and not ashamed of it. Anyway, it’ll hardly be as, um, explicit as what happened in Edward II and the Dream. And after all, it’s got a major place in the history of English theatre. Sam, you say you reckon it’s even more important than people think. Can you fill us in?”

I’d come prepared for this, and put on my geeky lecturing hat.

“It’s a matter of dates,” I said. “And of religion. Henry VIII of course broke with Rome and set up the Church of England. When he died in 1547 he was succeeded by his son Edward VI, who was only a boy but passionately in favour of the new protestantism. It was under him, in 1549, that the Book of Common Prayer was published, the first in English, and from then on it was illegal to use the old catholic Latin services. There were objections in Cornwall and Devon, where they rebelled and were bloodily put down. But everywhere else it caught on at once. Then in 1553 Edward died — he was only fifteen — and his half-sister Mary succeeded. She was a catholic, and of course she switched everything back to square one and protestants took cover. But she only lasted five years, and in 1558 Elizabeth became queen and turned England protestant again.

“Now Gammer was produced at Christ’s College in Cambridge. And the important point is that Cambridge — and Christ’s in particular — was strongly protestant. That’s underlined by the ribald anti-papist tone that runs all through Gammer. And William Stevenson was a Fellow of Christ’s from 1551 to 1561, except during Mary’s reign when he had to stand down because of his views. We don’t know exactly when he was born. But he was ordained in 1552, probably as soon as he reached twenty-one, which was then the minimum age. So most likely he was born in 1531. Does your family,” I asked Alex, “have a date?”

“Not for sure. But we think 1531 too.”

“Well, he went up to Christ’s in 1546. If we’re right, he was fifteen. That fits — in those days you went to university anywhere between twelve and sixteen. And he graduated in 1550 at nineteen, and was made a Fellow in 1551 at twenty. The college records show that they paid him for music in 1549, and put on a play of his almost every year from 1550 to 1559, except during Mary’s reign. They don’t give their titles, damn them, so it could have been a string of different plays. But much more likely it was the same play which was such a hit that it was repeated year after year. One payment is ‘to ye carpenter for setting up ye houses,’ which sounds just like what Rob’s doing — building Gammer’s and Chat’s houses.

“That’s guesswork, of course, because there’s been no firm date for Gammer. The first surviving edition — we call it the quarto — was published in 1575. But there’s a strong case for an earlier edition, though no copies have survived, published in 1562 under the title Diccon of Bedlam. That fits with what the quarto says — ‘played on stage not long ago, in Christ’s College’ — meaning the last performance in 1559. But it includes the phrase ‘in the king’s name,’ which means it must have been written before Edward VI died in 1553. After him, there weren’t any kings for fifty years. Only queens. And in fact we can take it further back still, to 1549 or earlier. To be precise, before 9th June 1549.”

I told them why, and that nobody seemed to have noticed it before.

“And that fits too. I reckon Gammer’s too vulgar for a Fellow to have written, especially one who’d just been ordained, or was about to be. Even young Fellows had their dignity to stand on. As I see it, it’s undergraduate humour. And because undergraduates were so young in those days, that’s the equivalent of our schoolboy humour. Stevenson wrote it when he was somewhere between fifteen and eighteen. The same as us.”

The others had been following closely, and nodded their understanding.

“And that means that Gammer isn’t just one of the first regular comedies in English, but the first. It’s pretty well agreed now that Ralph Roister Doister was written for Queen Mary in 1553. Gammer beats that by at least four years.”

“Brilliant!” they said, grinning.

I won’t bore you with a full account of the summer term. Everyone had exams which sadly had to take priority, and apart from occasional rehearsals Gammer stayed on the back burner. It was beginning to take shape, but the main donkey-work would come in the autumn. This was why Old Persimmon had changed the timetable. Alex’s voice, though, did break as predicted, and by Speech Day it had settled into a light tenor. He made a modest and creditable little speech, all the more creditable because it was in the presence of the Queen, who graced the celebrations of an institution to which the first Elizabeth had granted its charter 450 years before. And it was a good thing Gammer wasn’t scheduled for Speech Day. The Queen, like her great-great-grandma Victoria, might not have been amused.

I was coming to like Alex. Hitherto I hadn’t known him well. He was a cheerful young imp, still small for his age, with a pert face under curly dark hair. But he was modest, he could be serious, and his head was remarkably well screwed on. In a couple of years he’d probably be producing the play. I found myself talking to him quite often when time allowed, and learned that, as I’d guessed, he was deeply interested in his ancestor.

“But we aren’t likely to discover any more about him,” I warned. “The scholars have been through all the known archives with a fine-tooth comb. Unless you’ve got any family papers tucked away.”

“You never know,” he said thoughtfully. “We live in an old, old house. It’s on the site of a grange of Romsey Abbey. When Henry VIII dissolved the monasteries, William’s dad bought it off him and built the house. We’ve lived there ever since, and there’s tons of junk in the attic. There might be something. I’ll have a look. Maybe William can help.”

I assumed he meant a brother or a friend.

“Whereabouts is it?” I asked.

“Hampshire. Abbot’s Bumley.”

“Never heard of it. Where’s it near?”

“Bishop’s Bumley. But that’s a dump,” he said disparagingly. “It belonged,” he added as if to explain its dumpishness, “to the Bishop of Winchester.”

I hadn’t heard of Bishop’s Bumley either.

“Do you know Nether Wallop?”

I shook my head again.

“Oh. Well, about nine miles from Andover.” Got there at last. I had heard of Andover.

Another interesting development was that Alex spent more and more time in Hugo’s company. My suspicion grew that a romance was brewing. If so, good for Hugo. Alex was a far better bet than our Edward had been, and they were types who’d fit very well together.

*

So the summer holidays came. As usual I was not looking forward to them. Rob was temporarily out of circulation, staying with relatives in Dorset. But quite early one morning, after a fortnight of boredom, I had a phone call out of the blue. To my surprise it was Alex, in a state of obvious excitement.

“Sam! We’ve found something that looks important! Can you come over and have a dekko? Stay with us, for as long as it takes. Hugo’s here too.”

He refused to give any details. But it was a godsend. I browbeat my father and stepmother into granting me leave of absence, and leapt on a train. By two I was at Andover, being met by a battered Volvo — nice to find another family whose car was as battered as ours — by Alex, by Hugo, and by Alex’s mum who insisted on being called Charlotte and proved delightfully easy-going. In reply to my fevered questions they all gave a maddening ‘wait and see!’ After a few miles on the Salisbury road we turned off to meander along the lanes through Nether Wallop — an archetypal English village of thatched cottages set in archetypal rolling English countryside — and the despised Bishop’s Bumley, until we turned in to Bumley Grange. It was a large and rambling place, its brick and tiles a mellow red, its tall chimneys blatantly Tudor, and it had a run-down look.

“There used to be masses of land,” Alex said as we drove up. “William Stevenson’s dad was stinking rich. And William inherited the whole estate, plus enough dosh to found Hambledon. But most of it’s been sold off to pay for this and that, and now we’re down to three acres.”

Without ceremony the boys rushed me indoors and into the hall. I don’t mean the entrance hall, but The Hall, the main room of any substantial Tudor house. And God, what a room! Huge, high, its ceiling ornamentally plastered, its walls panelled in oak and hung with portraits. In the middle of one side was a vast fireplace. It being August, there was of course no fire in it, though to heat this cavern in winter they’d need a monster. Nonetheless the place felt warm and welcoming. By a window was a table at which they sat me down. Beside the table was a large and dusty carved chest. On the table was a sheaf of paper — thick firm paper — covered in brown writing. The hair rose on the back of my neck.

“We found the chest up in the attic, and this was in the chest. We can’t make head or tail of it. But we’re hoping against hope …”

We have it easy, these days. We write everything on PCs. We read Shakespeare & Co in neatly-printed texts, usually modernised in spelling and punctuation. Tudor handwriting is another matter. In my limited experience it varies from the painful to the impossible. Court hand isn’t too bad, the style they used for formal things like legal documents, written nice and regularly on vellum. I’d managed a few lines of Hambledon’s charter of 1559 which hung framed in the library there. Ordinary day-to-day scribblings with a dodgy quill are a different kettle of fish. Experts, of course, can read the stuff like yesterday’s newspaper, but while I knew I was a geek — it was why they’d whistled me up — I knew there were limits to my geekiness. But I had to try. And there was something indefinable in the atmosphere that was urging me to try.

This guy’s writing seemed to fall into the impossible category. At first glance I couldn’t make head or tail of it either. The layout of the top sheet certainly looked like a play, with lines of irregular length. But it didn’t look like the first page. Ah! In the top corner was a faint number 5. I scrabbled through the pile. Yes, the sheets were well and truly out of order. Forcing myself to be calm, I leafed through them until, near the end, I came to what obviously was the first page.

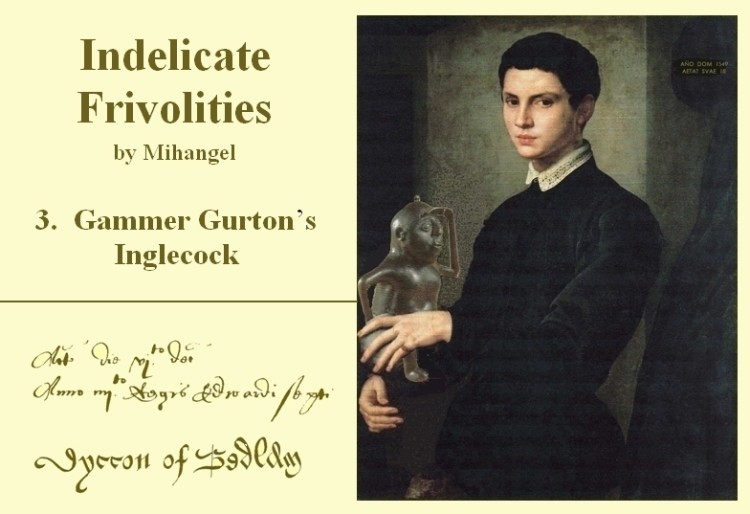

Most of it was covered with the usual scrawl, but at the top were two short lines of better writing. They were in Latin, and I could just about read them [see title picture]. Below them, in different and still better writing, was the title, in English. I could read that too. Easily.

As you may have noticed, I’m not much given to using the f-word. Not because I’m a prude, but because it seems to me to reflect poverty of language. Instead, on this occasion, I recall bellowing, “Bugger me backwards!”

I was on cloud nine, high above the earth. Alex and Hugo were down below shouting “What? What?”

I returned to earth enough to translate the words to them, pointing to each in turn.

“Acted the sixth day of December in the fourth year of King Edward VI. Dyccon of Bedlam.”

They both uttered the f-word, loudly. Charlotte, drawn by the din, came in and had to be told too.

“Well, tickle my pitcher!” she shrieked. I wasn’t quite sure what she meant, but subsequent research confirmed my suspicion.

“The sixth of December!” Hugo exclaimed. “That’s the same day as our show! And what’s the fourth year of Edward VI?”

I counted on my fingers. “1550.”

“And why’s that bit in Latin?”

“Added by a college official, I’d guess. A note that it had been accepted and performed.”

“And it really is Gammer, is it?” he asked anxiously. “Just with the other title?”

I was now like a cryptographer with the key to the code. Below the title the page launched straight into the text, with no list of characters. And because in our production the prologue was being spoken by Diccon, I had it by heart. As I slowly repeated it, the scribbles on the page began to fall into place. Old spellings, a minimum of punctuation, but they were the same. I had cracked the code.

As Gamer Gurton, with manye a wide stytche

Sat pesynge & patching of Hodg her mans briche

By chance or misfortune as shee her geare tost

In Hodge lether bryches her needle she lost.

“Yes, thank God,” I said, in huge relief. “It’s Gammer all right. Now … the first thing is to get the pages in order. Then I’ll have to go through the lot to see if there are any major differences. But it’s going to be a slow job, till I get my eye in.”

So we sorted the sheets according to their numbers, forty of them, written on both sides. From time to time we noticed that single words had been crossed out and replaced by others.

“Look at this!” said Alex suddenly. “There are whole lines crossed out here. One, two, three … nine of them. Oh no, eight — I think one’s split between two characters.”

A few sheets on, Hugo found a further pair of lines crossed out. But that was all.

“Well, let’s start with Hugo’s bit,” I suggested. “It’s shorter.” I got out my printed edition of Gammer in case it would help, and glared at the lines on either side of the crossing-out, trying to get an idea of whereabouts we were in the play.

Capital letters stood out from the rest, and there were five words in a row starting with capitals — H, K, C, T, S. The H surely belonged to Hodge. In the whole play I recalled only one capital K. Bingo! It was about Hodge’s date with Kirstian — ‘Hodge: Kirstian Clack Tom Simsons maid.’ Yes, and the next two lines fitted. Then came the two crossed-out lines. I wrestled with the wretched scrawl, comparing unknown letters and letter combinations with those I knew, and it took me half an hour to be sure of those two lines. And wow! What lines! I looked across at Hugo and Alex, bored by now and sitting on the sofa, heads together, chatting. Charlotte had long since disappeared somewhere.

“They’re your lines, Hugo,” I said. “Act II Scene 1. They’re about your relationship with Alex. This is what you say, unexpurgated.” (I give it here in modern spelling, the new lines in bold).

“Hodge: Kirstian Clack, Tom Simson’s maid, by the mass, comes hither

tomorrow.

I’m not able to say, between us what may hap.

She smiled on me last Sunday, when I put off my cap.

These five years past has been my sport to tumble Cock our boy,

But now I feel a pricking need to fill a maid with joy.”

They looked at each other and burst into hoots of laughter.

“Watch it, Hugo!” said Alex. “You keep clear of Kirstian, or else!”

“Wouldn’t touch her with a bargepole,” Hugo replied. “OK, Sam. So now you know about us. We’re in love.” My suspicions were confirmed. “That’s why I’m here. Not for this manuscript. We only found it last night. But I’ve been here since the end of term.”

“These two weeks past has been your sport to tumble Cock your boy?” I suggested slyly.

“I wish,” Hugo said, squeezing him. “God, I wish.” He swallowed whatever he was about to say. “I don’t call him Cock, though. I did try calling him Hernia, like Lysander did in the Dream.”

“Bit rude that, wasn’t it?”

“No ruder than calling him Cock. But when I started saying ‘Oh joy, oh rupture!’ he objected.”

Alex punched him. “And I wish too. Mum knows we’re in love. She’s very laid back about it. But she does draw the line at tumbling. Even at us sleeping in the same room. Still, it’s less than a year till I’m sixteen. Age of consent. I think she’ll say yes then.”

I marvelled at the love and trust that made him obey her. I wouldn’t have done so, not in these circumstances. “Roll on the day, then.” I said in sympathy. “OK, I’ll go back to the earlier lines. But they’re likely to take even longer. A couple of hours, maybe.”

It was now five. “That’s all right,” Alex said. “We’ll be eating about seven.”

“But can I use a computer? I may need to look things up online, and I’d like to type this up.”

“Sure. I’ll bring my laptop down.”

He plugged it in and, not being able to help, they went next door to watch cricket on the telly.

Although alone, I still had the odd feeling of a benign presence and, as my eye grew attuned to the idiosyncracies of William Stevenson’s handwriting, the job became easier. It was not much more than an hour before I was satisfied with the result. And it proved to be both a confirmation and a puzzlement. I typed it up, added what seemed to be appropriate stage directions, and went next door. Hugo and Alex were canoodling in front of the cricket, and I dragged them to the hall.

“Here you go,” I said, pointing to the screen. “Act I Scene 4.”

Cock [within]: I cannot get the candle light — here is almost no fire.

Hodge: I’ll hold thee a penny I’ll make ye come if that I may catch

thine ears!

Art deaf, thou whoreson boy? Cock, I say! Why, canst thou not hear us?

Cock: Tush, Hodge, I hear thee. I but move the inglecock

To blow the fire up.

[Noise within]

Hodge: By the mass! What the devil’s that knock?

Cock: God’s bones! Deep am I spitted! O that it should come to pass!

I backward fell, and the inglecock hath pricked me in mine arse.

[Emerges impaled by the inglecock]

Hodge: Thou cox! Thou whoreson ingle! Into thy shitten bum

Am I not the only neighbour whom thou allowest to come?

Stay still! I’ll draw this varlet cock forth from my Cock’s breech,

[Pulls it out]

And to admit no trespass more, so I shall him teach.

[Spanks him lustily]

Gammer: Beat him not, Hodge, but help the boy, and come you two together.

“Wow!” they cried as they read it.

“Nice, isn’t it?” I said. “I always thought there was more to those comings than meets the eye. But what the hell is an inglecock?”

They shrugged their shoulders.

“It sounds like a sort of bellows,” said Alex. “But how do I get it up my arse? What is an ingle, anyway? Thou cox, thou whoreson ingle — what does that mean?”

“Cox is a fool. Whoreson’s a term of abuse, son of a whore, like us calling someone a bastard without meaning it literally. Ingle means two things.” I clicked the screen to bring up the online Oxford English Dictionary which was lurking behind my script. “It can be a fire in the hearth. Hence inglenook, an alcove for the hearth, and presumably inglecock too, a cock for the hearth, whatever that means. And look — ingle can also be ‘a boy favourite (in bad sense), a catamite.’”

“What’s a catamite?”

I typed it in. ‘A boy,’ the dictionary told us, ‘kept for unnatural purposes.’

Alex was cross. “It isn’t unnatural.”

“Of course it isn’t. That’s just the OED being old-fashioned. Anyway, your revered ancestor’s got two lots of plays on words here. There’s ingle the hearth and ingle the boyfriend. And there’s cox the fool and Cock the boy and cock the prick and cock the something else. Cock means all sorts of things.” I typed it in. “Here you are. Noun 1, sense 20, a penis. Derived from sense 12, a short pipe or spout or nozzle. Hence stopcock, if it’s got a tap to turn it off. Which makes sense. After all, a penis is essentially a short pipe or nozzle or spout, isn’t it?”

Alex was giggling. “And once it starts spouting you can’t turn it off. Though I have seen one pipe that isn’t exactly short.” He put his hand on Hugo’s crotch.

“The problem,” I persisted in the face of this levity, “only arises when ingle and cock come together.”

“It isn’t a problem at all,” Alex said, now giggling fit to bust. “The cock arises when it meets the ingle. And once they’ve come together you can’t do much to stop it coming.”

“Even when the ingle has a shitten bum?” Hugo too was almost pissing himself with laughter.

“And Hugo!” Alex’s voice reverted to a squeak. “You’ve got to spank me!”

“Lustily. That means spank you hard!” They giggled on, until at last Hugo returned to the point. “Sorry, Sam. Let’s get back to the inglecock. We still haven’t got to the bottom of it.”

Which of course sent them off again.

“Cock,” I went on when the meeting was finally restored to order, “is trying to revive the fire. And therefore he tries to move the inglecock. But he falls backwards and knocks it over, which makes quite a shindig. And it pricks him in the arse. Impales him like meat on a spit. Hodge has to pull the thing out. So an inglecock must have some sort of spout or nozzle like a bellows does. But if you fall backwards onto a bellows it’ll hardly find its way into your arse. And inglecock isn’t in the OED, and there’s nothing relevant on Google. I’m floored.”

So were they. We printed out the new additions to the text, and we had to adjourn the meeting when Charlotte called us in to dinner. It was a great meal. Not just the food, but the atmosphere. She enquired, of course, about our progress, and Alex unconcernedly showed her the print-out. I couldn’t imagine showing such a thing to my own parents. And, where they would have gone through the ceiling, she didn’t turn a hair.

“It’s uncanny, isn’t it,” she said, “that you two should be cast, all unknowing, as Hodge and Cock, and should fall for each other. And here’s William prophesying it, almost. Giving you his blessing, in a way.”

“Well, I know he approves,” said Alex. “Don’t you, William?” he asked into thin air.

Honest truth, I swear I sensed a message of agreement from somewhere. Wondering if I’d actually heard it, I looked round. Charlotte laughed. “You won’t see him, Sam. Nobody ever has. But — I know it sounds daft — we often sense that he’s around. He’s not in the least eerie, just a comfortable presence. He’s not so obvious to me. Maybe it’s because I’m not a Stevenson by birth, or I’m the wrong gender. But he was obvious to Alex’s dad, and to his father. And he’s obvious to Alex.”

He was obvious to me too. I don’t think I’m unduly credulous, and I’m certainly not into ESP, but it was hard to deny what my senses told me. What a wonderful presence to have in the house.

“He lived here, you know,” said Alex. “He was born up north, but when his dad built this place the family came down, and William grew up here. His parents died when he was about fourteen, so from then on it was all his. He lived here too when he had to leave Cambridge under Mary. But soon after that he moved up to Durham and married. It wasn’t long before he died, though — he was only in his forties — and his wife and son came back here. We’ve been here ever since. And that chest in the attic’s probably been here ever since.”

“What else is in the chest?”

“We haven’t looked properly. All we’ve seen is masses of legal-looking stuff. Someone’ll have to plough through it, once we’ve sorted out Gammer. Once you’ve sorted her out.”

As the meal progressed, I learnt a number of things I hadn’t heard before. Alex’s father and grandfather had both died quite young — a worrying habit of the Stevensons, it seemed — before there was any chance of passing on family lore to their sons. That was why nobody living had any idea of what might be in the attic. And once her husband was gone, all of Charlotte’s energies were spent on bringing up Alex single-handedly and on making ends meet. She was a professional potter — and, I gathered, a highly successful one who exhibited all over the place — with her studio in one of the barns. Even so it was pretty clear, though she did not say so, that finances were tight. Giving a youngster as normal a lifestyle as possible and paying his fees at Hambledon, not to mention the prospect of university, does not come cheap. I knew that well. My father had often told me so. On top of that was the surely phenomenal cost of keeping a place like Bumley Grange going.

She excused herself to return to her pots, while we did the washing up. Then Alex showed me my room.

“It used to be the main bedroom,” he explained. “But when Dad died, Mum felt she was rattling around in it, it’s so big, and she moved to a smaller one. So now it’s just a guest room.”

Big it was. And its crowning glory was a great four-poster bed, complete with curtains.

“I’m sure William slept in that,” Alex said. “I slept here last holidays when my room was being patched up, and he was in it too. He wasn’t at all, um, off-putting. I mean, he didn’t mind me having a wank. In fact he seemed to approve.”

“Even though he was a reverend!” Hugo marvelled.

“Not all reverends are stuffy,” Alex pointed out. “Look at Crack.” He was the school chaplain. “Anyway, the William who’s around here isn’t old and stuffy. He’s quite young, about our age. And he thinks like us. I’m sure of that.”

The omens were good. But it was far too early to put them to the test, and the damned inglecock was still niggling me. I decided to go back to the laptop, and they sloped off to watch a Prom on the telly. The answer, I told myself, must be somewhere on the web. The problem, as usual, was how to find it. Google was useless on inglecocks. But what about searching under their function? The things were for blowing a fire, so I tried ‘fire-blower.’ Over four million hits, all of which — or at least the first hundred — were either about modern machines or about people who eat fire. Forget it. What about ‘hearth-blower’? Better, only 32,000 hits. I scrolled down the first page.

And there it was, or what might well be it. I clicked on it.

Cambridge University Press was announcing the contents of the Antiquaries Journal for 2007 which included an article on ‘Jack of Hilton and the history of the hearth-blower.’ It proved to be one of those maddening academic sites where you have to pay for what you want. But at least it gave a short abstract, which read:

‘The resurfacing of a late medieval hearth-blower for fanning the flames of a fire provides the opportunity for a review of the type. Examples of these anthropomorphic aeolipiles from England, all late medieval in date, are placed in context, both in time — stretching back to the Classical period — and in space.’

Uh? Anthropomorphic aeolipiles? Anthropomorphic I could do — in the shape of a man — but for aeolipile I had to return to the OED. ‘A pneumatic instrument or toy,’ it said, ‘illustrating the force with which vapour generated by heat in a closed vessel rushes out by a narrow aperture.’

Warmer, definitely warmer. But just how did it work? What did it look like, apart from a man? Well, there was still ‘Jack of Hilton’ to Google. I typed it in. Only 36 hits. One of them was an old book.

‘At Hilton, Staffordshire,’ it said, ‘there existed a hollow brass image representing a man kneeling in an indecorous position known as the Jack of Hilton. The image had two apertures, one very small at the mouth, another larger at the back. When filled with water and put to a strong fire, the water evaporated as in an aeolipile, and vented a constant blast from the mouth, blowing audibly, and making a sensible impression on the fire.’

I was beginning to understand the principle. And indecorous? That was even more interesting.

Another item, better still, was a report of the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford which had recently acquired none other than Jack of Hilton himself. It described him as a ‘hollow-cast copper alloy figure, 31 cm high, late 13th or 14th century. A rare example of an aeolipile: the vessel was filled with water and warmed on the hearth to fan the flames with a jet of air released through the steam—pressure created within.’

And alongside the description was a photo which showed just how indecorous he was. Eureka!

I ran next door and shouted to Hugo and Alex, who came bounding in.

“There you go!” I crowed. “There’s our inglecock! This one’s called Jack of Hilton.”

They goggled. “Well, he’s having a nice wank!” Hugo observed. “And look at those lovely balls! But I’m not with it. Does the air come out of his cock?”

“No. Out of his mouth.”

“But if he’s full of water,” Alex pointed out practically, “it wouldn’t be air. It would be steam. And wouldn’t that put the fire out?”

To that I had no answer.

“And look!” Hugo added, reading the description. “He’s a midget. He’s only a foot tall. So his cock can’t be more than a couple of inches long. When Cock gets impaled, it would hardly go in!”

“Maybe there were bigger inglecocks.”

“He’s not the only one, then?”

I showed them the abstract on the CUP site. “Looks like there are quite a number,” I said. “We’ve got to get hold of this article. But how do we find the Antiquaries Journal? Where’s the nearest decent library?”

“Bugger libraries!” cried Hugo. “You can buy it online. Look, it says so!”

“Yes, but it costs twenty quid.”

“No prob.”

I’d been forgetting that he, or his parents, were well heeled. He fished out his credit card and got busy. Within five minutes we had the article on screen and printed it off. It was highly informative. There were examples, though not anthropomorphic (“what does that mean?” asked Alex), from as far east as the Himalayas. From Europe nine anthropomorphic examples were known, of which three were of Roman date, three were medieval from the continent, and three were medieval from England. Like Jack, several had hard-ons, though none of the others was wanking. Most stood — or knelt — no taller than Jack. But one was 57 cm high.

“Almost two feet,” said Hugo. “That’s better.”

The article also explained the workings better. Fill the thing with water via a hole at the back of the head. Put a bung in the hole. Sit it in the embers until it boils. And the jet of steam coming out of the mouth entrains air with it, which blows up the fire.

“Why,” Hugo wanted to know, “can’t the steam come out of its cock instead?”

“Too low down,” Alex explained. “It’s under water. But maybe you’re supposed to think it’s the cock doing the work. Wanking into the fire.”

These things weren’t mentioned in contemporary literature, the article implied, and no contemporary name for them was known. We sat down on the big sofa to chew that over. Perhaps the name had simply gone unrecorded, except in Gammer. And what about the dates? None of the things was later than the fourteenth century. But Gammer was two centuries after that, give or take.

“William must have seen one, though,” I mused. “Can they have had one at Christ’s? In the hall? No, probably too risqué. But I wonder if there was one in his family, and it had come down as an heirloom. These things can’t have been cheap. You say the Stevensons were well off, Alex, even before they came here?”

“Oh yes. They had masses of land up in County Durham, round Bishop Auckland.”

“But if inglecocks weren’t cheap,” Hugo objected, “what’s one doing in Gammer’s house? She’s not much more than a peasant. She only owns one needle.”

“Gammer’s fiction, remember. A frivolity, miles away from real life. Anything to bring in a bit of fun. I still think William had seen one. Maybe even had one. And so he put it in his play …”

All three of us felt that warm young presence again. We looked at each other, and then at the fireplace. Its floor was of old brick laid in a herringbone pattern, on which stood a large and fairly modern basket grate, a pile of logs, a bucket of kindling, and a number of pokers and tongs. In that respect, an ordinary fireplace. But it was very big, and very old.

I was the first to put thoughts into words. “He was about seventeen. He’d invited a few of his mates from Christ’s to spend Christmas here. Maybe they tumbled each other, who knows? Anyway, they were sitting round this fire, well-fed, well-wined, giggling at the inglecock, making rude jokes just like we do. They’d seen a play or two at Christ’s and been bored by them — too decorous, or too nonsensical. William announced that he was going to write one himself. One that would be more fun. They threw out ideas. And one of them was to bring in the inglecock, which was sitting in front of them and wanking into the fire. Something like that.”

We sat there, visualising it. “Yes,” they said. “Something like that.”

We sat on, thinking. The room was rather different now, in August, not yet fully dark. Charlotte came in to offer us a hot drink. We turned it down, but put her in the picture. She studied Jack with interest, and laughed heartily. And her eyes too turned to the fireplace.

“You know,” said Hugo suddenly, “we’ve got to have an inglecock in the play, to impale Cock. But we can’t just go into a shop and buy one. We’ll have to get one made.”

We looked at each other again, and simultaneously we shouted “Rob!”

“Mum,” said Alex. “Can Rob stay here, if we can get him?”

“Of course.”

“D’you know where he is, Sam?”

“In Dorset, I think, though he’ll be going home soon. I’ll see if I can raise him.”

I got busy on my mobile, and Rob answered at once. “Sam! Nice to hear your cheerful voice! Where are you? What are you up to?”

“I’m at Alex’s, near Andover. Hugo’s here too. What we’re up to … well, it’s totally brilliant. Gammer stuff. Much too complicated to explain now. The point is, we need you. Urgently. You’re still in Dorset? And going home when? Tomorrow!”

“As ever is. And if you’re near Andover, it’s easy as falling off a bog. My train goes through Andover, so I can jump out there rather than carry on to London. I’ll square it with my parents. Can I stay at Alex’s?”

“Of course.”

“And how do I get there from Andover?”

“Hold on.” A quick word with Charlotte. “We’ll meet you at the station.”

“Great. I’ll find the exact time and text you. Till then!”

Alex and Hugo scuttled back to the telly to catch the end of their Prom, and Charlotte announced that she’d get a room ready for Rob.

“Oh, please!” I cried, alarmed. “Can’t he sleep in my bed?”

She gave me an unfathomable look. “Is that to save me the trouble of making up another? Or — how do I put it delicately? — is he your boyfriend?”

No doubt I blushed. “Yes, he is. But boyfriend sounds so, um, temporary. I’d rather call him my partner.”

She caught all the implications. “That sounds good and permanent.”

“Yes. It’s not just a trial. We fit. We’re going to stay together.”

“Then by all means sleep together … And in that case, Sam, may I ask your advice?”

“Of course.” What the heck did she want my advice about?

“And what about a dram of Scotch? I don’t often have one, but I need it today, and after all your labours I expect you do.”

“Thanks.” Rob had introduced me to Scotch at his home, and I had taken to it.

She poured it, and we sat down on the sofa.

“Sam, you know that I’ve put my foot down about Alex and Hugo sleeping together?” I nodded. “Well, I like to think I’m broad-minded. I find Gammer’s humour as funny as you do. I adore your inglecock. And I’ve nothing whatever against being gay. It’s the way you’re made. So if Alex is in love I can’t slap down on him. Where I have drawn the line is sex, at least till he hits the age of consent. And that’s because I know so little about Hugo. All right, he’s a personable and intelligent lad, and he comes across in a good light. But what’s he after? Love, or just sex? It’s an important distinction, isn’t it? Can you fill me in?”

I could, gladly. “His family’s rolling, and in that sense I think he’s a bit spoiled. But he isn’t spoiled in the bigger sense. He’s a great bloke. Time was when he was stand-offish. But now, if he’s with people on an equal footing, he’s considerate and he’s generous. He’s learnt it the hard way. He had an affair with another boy, but Edward was possessive and selfish and was after nothing but sex, and even that was all one-sided. Then six months ago Hugo had the sense to ditch him, and since then he’s been fine. Of course he wants sex — who doesn’t, at our age? — but he wants much more than that. Look, put it this way. Rob’s the best. But if I’d never met Rob, I’d happily live with Hugo. And I’m sure Alex will too. I can’t see any Kirstian putting a spanner in the works.”

“Thank you, Sam. That’s a good testimonial. You’re seventeen, aren’t you?” I nodded again. “A year older than Hugo, two years older than Alex. Before you arrived they were singing your praises. Not because you’re gay. They didn’t mention that, and I wasn’t aware of it till just now. But they’re right. You are competent and perceptive and responsible. Not that they used those words.”

Me? All of those? Well, Rob and I were going to be prefects next term, when we’d have to keep our noses reasonably clean. In other words be fairly responsible. Even so … I made a deprecatory noise.

“Oh, come off it, Sam! Look at your researches into Gammer — that’s competence. Look at what you’ve just told me — that’s perceptiveness. Look at producing a school play from scratch at sixteen — that’s responsibility … So you think they’re responsible enough? That it wouldn’t do any harm if I lifted the ban on sex?”

“I think,” I replied simply, “it would be good for them. Both of them. Because I know how good Rob’s been for me.”

“All right,” Charlotte said. “I’m persuaded. I’ll lift the ban. It’s great, you know, that you’ve all sussed out your sexuality so young. Leave it too late, and you’re liable to get hang-ups about it.”

Clinking glasses, we drained our Scotch, and she called Alex and Hugo in from next door.

“Boys, Sam and I have been having a chat. And so long as you’re clean and considerate, you’re now free to sleep together.”

It isn’t often that you see mouths literally drop open in astonishment. Alex gave his mum a great hug, and Hugo — to my astonishment — gave me one too. Then they swapped over. Then they disappeared eagerly to bed. I bade Charlotte good night and went up more sedately, thinking that I’d done my good deed for the day. Several good deeds, in fact, for surely Gammer and the inglecock counted too. William was there in my room. Whether he was off-putting I had no idea, because I dropped straight off in his four-poster without even contemplating any activity.

*

He was still there in the morning. I was woken, far too early, by a cock crowing. Cursing it, I found my mind impregnated with cocks: first with Gammer’s allegedly stolen cock, then with Cock the boy, then with the inglecock. I became aware of William trying to tell me something. Attic, he seemed to be saying, attic. He couldn’t mean … Or could he? Well, we must look. With that, I dropped off again.

When I resurfaced it was already after nine. I checked my mobile, finding a text from Rob that he’d be at Andover at 10.27. I swung hurriedly out of bed, washed, shaved and dressed, and went down to the kitchen. Unsurprisingly, there was no sign of the boys. But Charlotte was there, and she plied me with muesli and coffee.

On hearing Rob’s message, she said, “Forget about the boys. We must leave at ten. In other words PDQ. And do you mind if we drop in at Sainsbury’s on the way back?”

All I could do was scribble a note for Alex and Hugo to find when they should come down. ‘Look in attic for inglecock. William said so. I think.’

We picked up Rob, who was an instant hit with Charlotte. We went round Sainsbury’s which took, as usual, longer than expected, and it was midday before we were back. Rob and I, gentlemen that we were, carried the shopping in and helped Charlotte stash it away. On the kitchen table was a note from the boys that they’d fed the chickens and pigs and were now in the attic, searching. They came down, dustily, to welcome Rob with warmth and to throw me grins which confirmed that their night, as one might have guessed, had fully lived up to expectations. They returned to their search, dragging Charlotte with them, while I took Rob into the hall to introduce him to the manuscript, the new text, and the whole business of inglecocks and Jack of Hilton. As always on the ball, he readily hoisted in the complexities, and was not only fascinated but tickled pink.

“And I thought you said the Middle Ages didn’t show cocks on blokes!”

“I did, except on infants and sinners in hell. Jack & Co are the exception that proves the rule. Unless they’re regarded as sinners, roasting there by the fire.”

Then Charlotte reappeared, festooned with cobwebs, brandishing a feather duster, and excited.

“Guess what we’ve found!”

“Not the inglecock?”

“Better than that! We’ve found William!”

“Uh?”

There were footsteps on the stairs, slow and cautious, and in came Hugo and Alex, gingerly carrying something between them. It was large and flat and vertical, and its back was towards us. Grinning ecstatically, they turned so that we could see their burden.

It was a portrait in a heavy gilt frame, dirty and in need of professional cleaning, but riveting [see the title picture]. It was a young man or boy, dark-haired and attractive, very much like Alex if more shy in expression, soberly dressed in black doublet and lace collar. Behind his head, barely legible through the grime, were the words Anno Dom. 1549, aetat. suae 18. The date fitted William precisely. Most remarkable of all, perched on his right forearm and steadied by his left hand, was a Thing, podgy, bulbous and benign. It might almost have been a Thing From Outer Space, one stick-like arm akimbo, the other shading its eyes, and on top of its head was a little button.

Charlotte gave the portrait a quick whisk-over with her duster. “Put him up!” she ordered. “There!” And she pointed to the place of honour over the fireplace. Rob and I grabbed a chair apiece and climbed up to remove the current incumbent, a bewhiskered Victorian Stevenson who looked grumpy at being displaced. We dumped him against the wall. Rob took over from Alex who was hardly tall enough to reach, and he and Hugo lifted William and looped his hanging-chain over the hook. In deep content, we stood back to gaze. He was well-lit from the windows, and the whole room seemed filled with a glow of approval. It made Rob look curiously around.

“It’s William, Rob,” Alex explained. “He’s here. In spirit, I mean. And isn’t he great! Till now, we’ve never known what he looked like. It is William, isn’t it?”

“Oh, it must be,” I said. “1549, aged 18. And that must be his inglecock that he was so fond of. Not wanking, though. Its hands are in the wrong place. And if it’s got a hard-on, the painter’s discreetly hidden it behind William’s hand.”

It was incautious of me, I realised too late, to say things like that in front of Charlotte. But she was laughing with the rest.

“But why was he banished to the attic?” asked Hugo. “The most famous Stevenson of them all?”

“Do you think,” I suggested, “it was in Victorian times? Someone like him” — I pointed at the bewhiskered Victorian who was glaring at us from the floor — “was so shocked by the inglecock that he banished it. Remember what it said in that article, how the owner of one of the inglecocks chucked it into a pond, after hacking off its cock? And do you think William was banished at the same time because he was holding that disgusting inglecock? And because he’d written that shameless play?”

“Well, if William was dumped in the attic, was the inglecock dumped there too? Let’s have another look!”

Off Alex and Hugo dashed, ignoring Charlotte’s cries that it was time for lunch. We old ones — it struck me with horror that I was counting Rob and myself as old ones — shrugged at the impetuosity of youth, and went in search of food. But by common consent, having filled our plates with bread and cheese and pickles and our glasses with OJ, we took them back to the hall. There we continued our communion with William — with the portrait, that is, for the presence had wandered off, perhaps to the attic to help the boys.

Barely had we finished than there came a yell of triumph from upstairs. Down they came and, wonder of wonders, Alex was carrying the Thing itself. No, not itself. Himself, for from this moment I regarded him as a person. He was exactly as in the portrait, except that his very substantial member was on proud display. He was placed carefully on the hearth and, like worshippers before an idol, we knelt down to inspect him. He was not only better endowed than Jack of Hilton (even if lacking those balls), but better designed and made. He was … well, beautiful is probably the wrong word, so let us call him lovely. The bewhiskered Victorian seemed to be gnashing his teeth, until I turned his face to the wall. And through the whole room spread a sense of quiet satisfaction.

“He’s no taller than Jack,” Hugo pointed out. “But his cock’s a big improvement. Just what we wanted. Look, he’s got to have a name, like Jack of Hilton. What about Cock of Bumley?”

“Hey!” said Alex. “I’m Cock of Bumley. You can’t have two Cocks! Why not Jack of Bumley?”

As I gazed, I was inspired. “It’s his cock that matters!” I cried. “Look at his cock! In those days, needle could mean a cock. And his cock’s just like a needle! Remember how Hodge describes Gammer’s needle?

“A little thing with a hole in the end, as bright as any silver,

Small, long, sharp at the point, and straight as any pillar.

“Wasn’t he thinking of this needle? This cock? It’s got a hole in the end, it’s thin and long and sharp and straight. As they sat round the fire that evening, weren’t they joking about this needle? Isn’t this what gave William his big idea? ‘Ha!’ he said. ‘My play’s going to be about a needle!’”

“That’s right!” the presence seemed to say.

“So should we call him the Needle?” I asked. “The Bumley Needle?”

Charlotte dragged the boys to the kitchen to force-feed them with some lunch, and as they went they shouted, “There’s an ancient fireback up there too. And a whopping big pair of stand things. Far right-hand corner.”

So Rob and I went up and found them. The fireback was decorated with a complex coat of arms, and the ‘stand things’ were large fire dogs to support the logs burning on the hearth. With much grunting, for they were all of solid iron, we carried them down and, having removed the basket grate, set them in place. Rob then went into professional mode. He toyed with the Needle, stroked him, tapped him, shook him, peered at him from every angle.

“Intriguing,” he declared. “So simple. Apparently so effective. But how effective is he really? Shall we ask if we can try him?”

“It won’t hurt him?”

“I don’t see how it can. He’s good thick bronze. He isn’t cracked at all.”

And Charlotte, when asked, agreed. So Rob laid the fire and, with the help of newspaper and a firelighter which would hardly have been available in Tudor times, got it going. Then he weighed the Needle on the kitchen scales, filled him with water through the hole in the back of his neck, and whittled a bung from a piece of kindling. With everybody crowded around, he ceremonially placed him beside the logs. The fire blazed merrily, and we waited until a good bed of ashes should accumulate and the inglecock should heat up and show his paces.

“Let’s make sure I’ve got this right,” Rob said. “When Cock’s impaled by the Needle he’s indoors and out of sight. When he emerges he’s still impaled, until Hodge pulls it out. That right?”

“Yes.”

“Two problems, then. First of all, we can’t use the real Needle. Even when empty he weighs fifteen pounds. Much too heavy to be dragged along behind, even if Cock crawls out on hands and knees. So what we need is a light-weight mock-up. Papier-mâché, I’d suggest. And bigger, to make him more obvious to people in the back row. OK?”

We chewed it over, and it made every sense. “Can you make one?”

“Yes, I could, though it’d take a bit of time. But the other problem’s tougher. We know what inglecocks look like, and what they’re for, and how they work. But who else does? The audience’ll hear Cock yelling that he’s been spitted by the inglecock, but they won’t have a clue what he’s on about. They’ll see him crawl out with a weird thing up his bum — or supposedly up his bum, unless you’re going in for ultra-realism — but they won’t have set eyes on one before. They won’t have a clue what it is. The joke’ll fall flat. And I’d guess the same applied originally. Like us, William and his mates knew all about it. But you say that these things weren’t common. So how many of the original audience would have cottoned on?”

There spoke the voice of cold reason, and it was a dampener.

“Maybe that’s why those lines were crossed out,” I suggested. “OK, they may have been too coarse even for Christ’s. But did William realise, even though the joke was good, that it couldn’t be staged? And that anyway the joke would fall flat?”

“So does it mean,” Hugo asked dejectedly, “that we can’t stage it either?”

Rob, intent on the hearth, was not listening. The rest of us sat morosely, sweltering on an August day in the heat of a big fire. Its first blaze was dying off. And at that point we became aware that the Needle was beginning to whistle, or rather to hiss. His cock indeed looked at if it was pissing into the fire, and the jet of steam from his mouth could not be seen. But when Rob gingerly redirected the aim, its effect on the glowing logs was immediate. They flared up again and Rob, risking scorched hands and face, was studying the flames close-up and testing the force of the jet by holding a short-lived piece of paper in it.

“Impressive!” he said, retreating. “And the colour of those flames … it’s giving me ideas … But you were saying. No, we don’t have to drop the whole thing. One way round is to use the programme notes to explain. There will be programme notes, won’t there? A learned discourse by Hugo Spencer about our revered Founder, about Gammer’s place in literary history, about the new manuscript, about the production?”

Hugo blushed. “Oh yes.” I knew that his discourse was already in draft. He had consulted me a number of times. After yesterday and today, it was going to need a lot of revision.

“There you are, then. Include a bit about inglecocks and how they worked.”

“Lots of people, though,” Hugo pointed out, “don’t read the programme before the performance. They’re too busy gabbing to their mates. But it’s dawning on me — there ought to be a special advance exhibition of what we’ve found here. Old Persimmon and the headmaster’d jump at it. Display the manuscript — though we mustn’t release the new lines in advance. And the portrait. And the Needle, with a diagram of how he works. Always assuming,” he turned to Charlotte, “that you’d be willing to lend them.”

“They’re not mine to lend. The house and its contents are Alex’s, in trust till he comes of age. Though as a trustee I may have a say. In which case I’d say yes.”

“And so would I!” cried Alex, his face aglow and not only with the heat.

“Good,” said Rob. “The more ways of hammering the message in, the better. The other thing I’m wondering about means redesigning the set. How about this? Gammer’s house — just Gammer’s, not Chat’s — has a removable front, sliding on rails. When the audience comes in, the curtain’s already up and you can see the inside of the house as well as the street. People are being ordinary. Gammer’s sewing. Chat’s passing by. Hodge is picking up his spade to go digging. Cock’s feeding the hens and pigs or something.”

“Oh, can we have real hens and pigs?” asked Alex eagerly. “Ours. Or some of them. In the street. They’d add extra colour.”

My heart sank. There’s an old theatrical saying that infants and animals on stage invite disaster. Mercifully, my suggestion of a dummy cat rather than a real one had already been adopted.

“That’s only a detail, Alex,” said Hugo, very properly. “Go on, Rob.”

“And Tib’s tending the fire against the back wall. The Needle’s very prominent and appears to be blowing on the logs. We can’t have a genuine fire, of course — health and safety — but I could rig up one of those electric fires with a realistic flame effect, and use a rheostat to make it glow brighter and brighter. So there’ll be plenty of time for the message to sink in — that’s what an inglecock looks like, and that’s what it does. And then a drop comes down, dividing the street from the house. We won’t need much time to roll the house front in, and with nylon runners it shouldn’t make any noise. So at that point Diccon toddles on, says the prologue, and toddles off. The drop goes up, and off you go. What about that?”

Trust Rob to work out the practicalities. There was eager agreement. And Alex resurrected the idea of his livestock. He dragged us into the garden to admire them. I hadn’t set foot there before, and it was very charming, not because it was neat and tidy, which it wasn’t, but because of its setting between the mellow brick walls and the little River Didder which chuckled past. Alex clearly had a way with animals. There was a large coop for the chickens, and a large run for them. He clucked endearingly and they scuttled towards him. Hugo clucked endearingly and they scuttled off in horror. Scope for a laugh there, I admitted, could it be repeated on stage. Then the pigs. Two large sows, one a very recent mother with a tribe of littl’uns. Alex grunted, and one littl’un scampered over to be tickled.

“His name,” Alex told us with great originality, “is Piglet. He’ll be weaned by December. He’d go down a bomb.”

Hugo seemed halfway to being convinced, but I stayed aloof. If they joined the cast, I would have nothing to do with them.

That night Rob joined me in William’s four-poster, and William gave us his blessing. After all, it was perfectly possible that he’d tumbled his own mates in it.

*

The next ten days need not be chronicled in detail. They were a time of hard work for everyone. Charlotte potted. Hugo pondered the production and laboured over his learned discourse. Alex helped Rob. And Rob concentrated on the papier-mâché Needle. He scrunched up chicken wire to the right shape and size — half as big again as the original — as the frame on which to build up the skin, for which Alex mixed paste and tore up old newspapers in prodigious quantity.

In two areas Rob had to innovate. He argued that the audience would better understand the inglecock, when on display at Gammer’s hearth, if steam was seen to be issuing from its mouth. In our experiment on the fire, the steam had been invisible because the temperature was too high for it to condense. But with a lower ambient temperature, the jet would be visible. So he built into his wire skeleton a tube running from the mouth to the back of the head. Into this would be plugged a rubber pipe leading behind the scenes to an electric kettle. Tests worked brilliantly.

Secondly, how was the Needle to be attached to Cock as he crawled, impaled, out of the house? Hugo vetoed Alex’s noble offer to have it up his arse for real. Instead, Rob stitched a crudely rustic jerkin, very short in length in order to allow the Needle easy access; and, for Alex to wear under it, he adapted a pair of tight briefs. To their crotch, on the outside, he sewed a tube of fabric into which the Needle’s cock fitted tightly enough to stay put as Cock crawled, but loosely enough for Hodge to pull it out. This being a matter of very delicate adjustment, endless fittings were required, which they did in decent privacy. But once I overheard them.

“Right,” Rob ordered. “Pants off.”

“Jerkin off?”

“If you must. But by yourself. I don’t do it with anyone but Sam.”