The year was 1941 and the month was December. America wasn’t at war yet and photojournalist Johnny needed a sale but what he got instead would change his life forever. Sailing into the Pacific just as the Japanese launch their world-shaking naval offensive, Johnny isn’t looking for love. But he meets a man who could only have come from the depths…of his dreams.

[This is a true story and it involves male-male affection so if either truth or love offend you, I suggest you find something else to read. This story is under copyright and legally protected against infringement. Events are presented exactly as told to me; only the names have been changed and any mistakes in transcription are my own. Read my other stories at www.tragicrabbit.org and www.awesomedude.org –Tragic Rabbit]

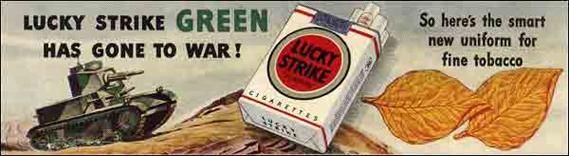

Lucky Strike Hit Parade 1941

“We’re waltzing in the wonder of why we’re here,

Time hurries by; we’re here and we’re gone…” Artie Shaw sings Dancing in the Dark on your Lucky Strike Hit Parade; we’re bringing you all the hits of 1941. Remember: LS/MFT… Lucky Strike Means Fine Tobacco!

There’s no use my telling you this story, kid, you’ll never believe me, no one ever does…but if you keep on buying the drinks, what the hell. I mean, I got no proof, I admit that. Oh, I had pictures; I had some amazing color shots off my Speed Graphic but naturally the damn Navy impounded them after the shit hit the fan. Hell, I was lucky not to end up in prison or something; the way OSS was sniffing around. Wartime security and all that crap. Sure, I was arrested but by the time ‘42 rolled around, I was sent home with a warning and it was like nothin’ happened. Nothing besides the goddam war, of course. Jesus. And all I started out with was a lead on a human-interest thing, you know, how the Coast Guard was keeping America safe and all that. Just something plain and simple for the folks in the Midwest, nice clean-cut American boys at sea. I mean, who knew? Not me, that’s for damn sure.

I was in Memphis, trying to sell a portfolio of crap photos no one was buying when a friend of mine called, guy in a West Coast PAO, with a story idea. The Coast Guard had just been pulled into the thing back then, and this was before the war you know, before the Japs hit Pearl Harbor, and he thought a photo workup with some nice wholesome interviews would sell. I mean, looking back, Hawaii was a hell of a place to take off to photograph the scenery in late ‘41 but like I say, who knew?

So I packed up my cameras and headed for Oahu. I had no idea that the next time I saw the mainland; we’d be in the shit, fighting on three continents and saving tin for the war effort. Ration books, blackouts and a gold star in the window for each loved one overseas. You kids can’t imagine what it was like then. But this was before, this was the first of December ’41 and I was on a train to California. Even then, you couldn’t get a seat sometimes with all the soldiers and sailors coming off of leave, plus a few headed home early for Christmas. I guess, looking back, I should have guessed something was coming up, something big. But I just wanted a story to pay the bills and I didn’t mind climbing in and out of a bunch of boats to get it if I had to.

I got a seat on an Army Air Corp plane out of San Fran; somebody got bumped after I called my PAO buddy. The Navy was looking for a happy story to reassure everyone, I guess, with all the Jap attack scares, but that didn’t make the soldiers any less pissy when they lost their seat to a civilian and had to sleep in the airport. Can’t say I blame them but, now and then, a journalist actually does get a perk or two. Not that I felt that way riding the chop out of the Bay, I damn near lost the crummy $1.50 diner meal I’d barely had time to wolf down. Still, they got me there in one piece and with all my equipment. They had a berth for me at the base, Pearl Harbor, and I sure was damn glad to see it at two A.M. I checked my lenses and put a fresh Kodak Yellow box of film in the outer pocket of my bag. I figured if nothing else, Hawaii was good for some pretty beaches and pretty girls in swimsuits. You gotta be practical when you’re a shooter for pay, you gotta have dollar signs in the back of your mind all the time.

If you’ve never been woken up against your will by a goddam Navy whistle after three hours sleep, then you’re a luckier man than me. Damn thing must have been heard for miles, is all I can say. Of course, the base there is pretty much the whole island, or it was then, so I guess nobody minded much. Or if they did, they sure weren’t complaining where the brass could hear. Not so the sailors I was berthed with, their complaints were pretty damn colorful, I picked up a few new words just that first morning. Some of them were even English. Anyhow, I ended up down in the harbor with an escort from Port Operations, some fresh faced kid who’d looked like he’d survived a freckle bomb detonation and holding a sheaf of magic papers that managed to get a civilian photographer through all the checkpoints and right up to the gangway of the USCGC Walnut. But apparently no further.

It looked like the C.O. wasn’t too keen to take on a passenger. He stood on the deck, shading his eyes in the morning sun to read the papers thrust at him by Lt. Freckle and shaking his head. Suddenly, the kid pointed over at me. The C.O. turned and met my eyes over the expanse of water between us. I don’t know how I knew it then and at that distance but I did, his eyes were as blue as the Pacific, dark and intense as he stared at me. He was a broad shouldered guy, muscled arms straining the short sleeves of his uniform shirt, hair bleached by the sun, his thick hands making the sheaf of papers look smaller than it had looked in the young lieutenant’s fingers. I was definitely under inspection. I shoved both my fists down in the pockets of the fisherman’s vest I wore to keep equipment in and suddenly felt like carefully examining my shoes.

When I looked up, the C.O. was smiling and the kid louie was headed back. I hardly noticed him as he handed over my copies of the papers and a laminated NRSH security pass and then left me there with my bags at my feet. The BM3 that escorted me across must have thought I was a real klutz; I nearly dropped my camera bag in the drink because I kept looking up but couldn’t see the C.O. I guess a civilian on board wasn’t interesting enough to keep him from his morning duties. Seems they had orders and were casting off, the whistle blasted twice just as I got my gear stowed in the tiny cabin the CPO finally found for me. I couldn’t complain about space, I guess, at least it was a private berth.

I loaded a sheet into my Speed Graphic, stuck a couple flashbulbs in my vest pockets and headed up topside to see what I could see. I got a few nice shots as the cutter pulled out, nothing fancy, the usual gorgeous views of paradise. The Walnut was a 175-foot, 32-foot beam buoy tender; steel-hulled, twin-screwed, and steam-powered. No big guns but sporting a steel boom and hydraulic hoist; she ran rescue ops and security checks up and down the northernmost Pacific in an ocean poised for war.

I walked the deck, getting those pretty shots and making friendly with the crew. We were headed northwest at a smooth 10 knots to the naval base at Midway according to Joe, a talkative, skinny dark skinned sailor with the look of a South Sea native. Looking back, it’s amazing how casual we all were about the Japs. Despite the scares, I don’t think any of us really believed they were a threat, we thought those little men were cowards, no match for us Americans. The Japs were a joke those days, tiny yellow men with big buckteeth in the Sunday funny papers.

The ocean was flat and calm and just seemed to go on forever like a shimmering cloth as you looked ahead towards Tokyo and the Mysterious Orient. I finally lit a Lucky Strike (still in the old green wrapper, back before Lucky Strike went to war with the all rest of America) and leaned into the aft railing, to watch the water cutting to each side in the ship’s wake. Somewhere a tinny radio was playing Glenn Miller’s You and then segueing into Tommy Tucker, those smooth all-American notes floating out in the morning sunshine. It all seemed so peaceful.

Just goes to show, you never can tell.

“I don’t want to set the world on fire,

I just want to start a flame in your heart…” Tommy Tucker on your Lucky Strike Hit Parade. Smoke Lucky Strike-It’s Toasted!

Late afternoon, three days out and nearly to Midway, I was up on deck sliding another sheet into the Speed Graphic. I’d got dozens of great ocean shots but how many of those does it take to buy a cuppa coffee in Milwaukee? I mean, nice is nice but I needed something more if I wanted to sell to anybody with circulation. Those film sheets were bulky, even after they came out of the wooden sleeves, so I couldn’t take a thousand of ‘em but the results I got were worth it. Still, now I had all my basic pretty ocean shots; I needed something more but couldn’t think what. I finally stopped beside the pile of anchor tackle amidships. Out across the ocean, birds wheeled and called, we were making ten knots but still it seemed at times as if we were suspended motionless on an enormous empty sea.

I slung the camera bag’s strap over my shoulder and fished out another pack of smokes. This had the usual result: a buncha swabbies either off duty or taking it easy, hard to tell the difference if you ask me, suddenly appeared, bumming smokes and passing around my Zippo. A couple guys leaned against the ground tackle to smoke, Joe and a black haired Irishman named Sean who’d already let me know he found civilians almost beneath contempt. Not that his was a minority view. It was a good thing I’d been around enough to know to carry extra smokes or I’d have been as unpopular as a nun at an orgy. So I’d brought my usual stash of smokes and cash along. If there’s one thing journalism teaches you, its that you gotta have the quid to get the quo, and if you want their cooperation, you’d better be buying. So there I was, passing out Camels and Lucky Strikes and paying attention. Not that anything was happening but, like I say, you just never can tell.

Billy, a tousle haired kid that frankly didn’t look old enough to be away from his momma, flicked the ash from his Camel with long practiced ease and looked up at me with a Huck Finn grin.

“Hey, Johnny,” Billy said to me, his voice straining not to break as he surreptitiously checked to see that he had the other men’s attention.

“You hear the one about the ant and the elephant?” Billy asked me earnestly. Joe rolled his eyes where the kid could see; earning him a kick on the shin that had to hurt but Joe didn’t blink. Or budge.

I just smile and tapped out another cig.

“No, Billy, what about the ant and the elephant?” I could play straight man; it went with the job. Even if it was to a smudge faced kid.

“Mr. Ant is walking through the woods,” Billy says, “and comes to a huge hole. At the bottom of the hole is an elephant trying real hard to get out. Being the compassionate type, Mr. Ant calls down, "Say, Mr. Elephant, would you like some help?" And Mr. Elephant, since he can’t get out by himself, agrees pretty fast. So Mr. Ant backs his shiny new Packard up to the hole and throws a rope to Mr. Elephant. When everything is tied off, Mr. Ant jumps in his car and pulls that big elephant right out. Mr. Elephant is real grateful and offers to return the favor some time.”

Sean is watching the kid. Joe’s snickering. Maybe he’s heard it before.

“A while later,” Billy continues, “Mr. Ant is stuck in a hole and he sees Mr. Elephant stroll by. Naturally he calls out for help. Now, everybody knows elephants don’t never forget, so Mr. Elephant is real happy to help. So he stands over that hole and lowers his big ol’ dick down to the bottom. Mr. Ant walks right up that giant schlong and out of the hole. Mr. Ant thanks Mr. Elephant and the two go on about their business.”

Billy is grinning wide enough to break his cheeks and Sean’s eyebrow’s raised, the only sign he’s waiting for the punch line. Billy has an innocent look that’s not all that hard for his baby face to pull off.

“The moral is, "If you got a BIG dick, you don't need a shiny new Packard!” Billy says, eyes shining.

Joe chortles, despite himself, and Sean tries not to laugh. I’m laughing; of course, I’d laugh even if it weren’t funny. That’s more Journalism 101, how to make friends and influence people. And make your deadlines. Billy’s so happy he can’t stand it, he told a dirty joke to grown men and made ‘em laugh. Was I ever that young? I’m pretty sure I wasn’t. Sean has an odd look on his round face now; he’s watching me.

“If ya like stories, Johnny boy, I got one for ya.” Sean says, his smile gone and his face serious. I’m immediately cautious, if I know anything, I know the Irish. My own father, God rest his drunken soul, was Chicago Irish. Billy pulls another pack from my vest without asking, pulling rank over a civilian, I guess. I don’t mind. Joe’s against the tackle in that relaxed posture, that nonchalance all seamen affect anytime there’s no officer around.

“What story’s that?” I ask Sean, leaning back against the bulkhead and partway into the shade. Another guy walks over but I can’t see who it is with that sun in my eyes. Joe straightened up and ground out his cigarette.

“Well, see now, your cabin? She’s haunted.” Sean says in a calm voice, ignoring the sound Billy made that might have been a laugh or might not.

“Really?” I asked, willing to play along.

Sean frowns. “I’m serious, Johnny, that cabin’s got a ghost.”

I smile. “Uh-huh. Maybe he’s on vacation, I haven’t seen him.”

Sean shakes his head. “You don’t see him, you hear him. At night. Heard anything in the bulkhead maybe? A tapping? Or maybe footsteps after lights out?”

I shook my head, still smiling. Was he kidding or what? You never knew with the Irish, they could tell the most outrageous stories and smile…but mean every single word. They could also pull both your legs and pick your pockets without you even noticing. I kept smiling. Sean was watching me, his black eyes intent.

“You’re laughing, boyo, but that cabin’s haunted. A kid died in there, hung hisself after he caught his wife under his best pal.” Sean’s voice was low, Billy was holding his breath and watching me.

“Look, you guys aren’t putting anything like that over on me, I don’t believe in ghosts.” I said firmly, but gently. Sean made a disgusted sound and another voice spoke up.

“It looks like our visitor isn’t the gullible type.” This was the new guy, the one who’d walked over. He had leaned forward into the shade to speak and now I could see his face better.

It was the C.O., his buzz cut bleached almost white and his forearms tanned from the Pacific sun. I noticed the other guys were sitting up a little and only Sean still had a cigarette in his hand. The C.O. grinned at me and stuck out his hand.

“Jimmy Newsom. Sorry we haven’t met but I heard you were getting on okay without me.”

“Yeah, pretty well, thanks.” I said, feeling a little foolish sitting here listening to ghost stories on a sunlit ship with a war going on in Europe. Some serious journalist I was.

“Guess you don’t go for ghost stories. You probably don’t fall for fish stories either, I bet.” Jimmy said. Smiling like a cat. Billy was biting his lower lip and trying not to bounce like the kid he was. I narrowed my eyes and looked around at all of them.

“No, I don’t. I’ve seen a lot of crazy stuff, heard a lot more, enough to know that half of what you hear isn’t worth much. I mean, I may look like a mark but I’ve been around. I don’t believe in ghosts, no.” I said, feeling a lot less sure of myself than I had a minute ago. Jimmy’s blue eyes were boring into my head, a contrast to his open, white-toothed smile. Joe was laughing softly.

“Heard many fish stories, have ya, Johnny?” Sean asked quietly. I could hear the gulls that followed the ship and the far off sound of bells. I felt in my pockets for my smokes.

“A few.” I admitted cautiously.

“What if we could tell you a fish story you’d never heard before?” Jimmy asked, studying my face. They were all watching me a little closer than I cared for. This must be the setup before my really big fall, I guessed. Razzing the civvies, a source of fun for seamen through the ages.

“Would you like to swing on a star, carry moonbeams home in a jar?”…You’re enjoying Frankie Sinatra on Your Lucky Strike Hit Parade. Remember: When Temptation Strikes-Reach For a Lucky Instead of a Treat!

I tapped my camera bag. “Oh, I’ll believe anything you tell me.” I said, mildly sarcastic. “Just show me where to set up my camera.”

Sean yelped. A laugh, I was pretty sure. Billy snickered and Jimmy just kept staring at me.

“I’ve been wondering about you, Johnny. Wondering if we should tell you about Pu’uloa.” Jimmy said, his voice gone very soft. Several other crewmen had come up and were listening, not speaking, and watching their commander.

“Poo loa.” I repeated.

“Pu’uloa.” Jimmy corrected. “That’s Hawaiian for Pearl Harbor, where you got on.”

“Okaaay.” I was willing to go along.

“Pu’uloa…and Ka’ahupahau.” Jimmy amended.

“Gesundheit.” I said. Joe frowned.

“Ka’ahupahau is…well, she’s a sort of princess.” Joe said.

“And her brother.” Billy interjected.

Joe nodded. “She lives underwater with her people in the Honolulu harbor; Pearl Harbor, Pu’uloa.”

The man looked serious and he wasn’t even Irish.

“Underwater.” I repeated.

“In a cave.” Billy added helpfully. “They protect the harbor. Follow along with ships, too, sometimes.”

“Right. An underwater cave.” I said. I was willing to go along, but only so far. Jimmy and Sean were watching this interchange intently, the other crewmen silent behind them. This was pretty weird, even for sailors, but I wasn’t buying.

“Whaddaya think, Cap?” Sean asked Jimmy without taking his eyes from me. Jimmy seemed to look me over thoughtfully.

“Dunno. She did say she wants to meet him. Said she would meet him, actually.” Jimmy said finally. “Me, I’m not so sure. She said it was…foretold. In dreams.” Now they all seemed thoughtful as they watched me. This was just too weird. I mean, a joke’s a joke, right?

“She, who? Your Hawaiian princess?” I asked, annoyed. Billy still had my Zippo. I reached for it.

Jimmy smiled that cat smile again.

“Yeah, our Hawaiian princess wants to meet you,” he said, those intense blue eyes glinting like sunlight off the ocean.

I rolled my eyes and stood up, gesturing to Billy for my lighter. They all stood up right after I did and Sean grabbed onto my shoulder. Joe slid my camera bag off my shoulder and I protested, reaching for it.

“Hey!”

Joe shook his head.

“Wouldn’t want you to drop this, yanno, in surprise or anything.” Joe said by way of not explaining. Sean’s fingers were digging painfully into my bicep. They were walking me around to the leeward side and I had visions of pirates and walking the plank. Were these guys crazy or what? I was past my limit for playing along and just wanted to get back to the cabin, small as it was. Even haunted. This didn’t seem friendly any more. But then I looked over at Jimmy. He was smiling grimly, but definitely smiling. The ocean was clear and smooth out past the hull; the sun bright as diamonds overhead.

“You might want to take those clothes off, Johnny boy.” Sean said in my ear.

“I’m not going skinny dipping in the Pacific Ocean.” I said, feeling pretty angry by this time.

Joe laughed and Jimmy shook his head.

“No, not exactly. But you should get out of your shoes and shirt at least.” Jimmy told me, shucking his own clothes as he said it. He peeled off his shirt to reveal a muscular chest covered in blond hair from his navel to his neck, with only a slightly whiter shade of tanned skin under the shirt. He began unbuttoning his tight white uniform pants and I swallowed. This could get awkward and fast.

“Um…” was all that came out of my mouth. Billy laughed and reached for the top button of my pants.

“Hey!” I said, pulling back, “I can do it myself, thanks.” I pulled off the loose shirt I’d worn on deck and started unbuttoning my slacks, turning away to slide them off. I wished I’d worn a swimsuit but, then, I didn’t own one, I didn’t even know how to swim and, hell, who swam on the ocean anyway? Jimmy was down to his skivvies, which turned out to be a black bathing suit. What, did they do this every day?

I started to get mad again, standing there in my boxers that, unfortunately, were the red silk ones a close friend had given me last Christmas. I felt like an idiot. I was trying not to look at the rather fit body of the C.O. and trying not to think of why only the two of us were stripping in a crowd of sailors. There were a couple loud splashes off the side and Jimmy grinned, looking suddenly like a kid himself, younger even than Billy. He grabbed the railing and swung out onto a Jacob’s ladder tied to the side. He began to climb, his wheat white hair disappearing as he went down the rope ladder. Some of the crew went to the rail and looked over, whispering and talking. One pointed out to sea and called something I couldn’t hear. I could hear Jimmy laughing down near the water, against the hull, I supposed. Then I heard what sounded like a woman’s voice.

About that time, my curiosity got the better of my good sense and I went toward the opening in the rail. Sean stepped aside with a grand sweep of his hand, gesturing me forward with a mocking expression. I knelt down at the rail, unwilling to actually get onto the ladder but curious as a cat. The wind off the ocean felt almost cold, despite the sun, the breeze brushing against my exposed skin and flapping the silk legs of my boxers. I looked down to the shining waterline. Jimmy was hanging from a lower rung of the knotted rope ladder, one arm wound around the rope and the other stretched out to his companion. Jimmy was laughing, throwing back his head in a carefree way that would have been striking if the sight of his companion hadn’t shut down my entire frontal lobe.

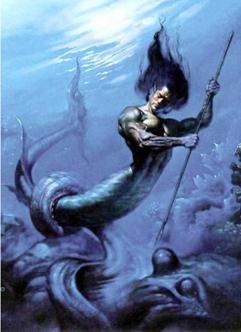

Jimmy’s outstretched hand was running through the long, straight black hair of a very beautiful, very graceful woman whose right hand was holding onto a low rung of the rope ladder. She was smiling into Jimmy’s face and talking animatedly in a voice I could only catch here and there, some kind of singsong language that sounded exotic. But not as exotic as she herself was. She was dark skinned and slender; she wore no clothing and her bare small breasts and dark nipples glistened with droplets of water. Below those naked breasts, her flat belly tapered off into a sleek form partly obscured by the water she was half immersed in, the waves lapping gently at the hull. I think I would have fainted then if Joe hadn’t caught me and held me tightly against him. The beautiful naked woman didn’t have legs. She had a tail.

The woman was a mermaid. Yeah, kid, I said mermaid.

She glanced up, caught me looking at her and laughed aloud, the sound like dainty bells chiming. I blinked and looked again. No question, that lovely lady was a fish. She gestured to me with slender fingers, beckoning. I couldn’t hear anything around me on the ship, not the distant radio or the birds or the voices of the crew, all I could hear were the sounds of her voice and the tiny shells that were strung through her dark hair, tapping against one another whenever she moved. She smiled up at me and held out her hand. I put one foot on the ladder, not taking my eyes off her and the sight of a nearly naked Jimmy stroking her hair. I swung out onto the ladder and it felt like the world was spinning.

Fish stories, huh? I wondered if I could get the Speed Graphic down the ladder and hold it steady enough to shoot. I wondered if Life magazine paid extra for stunning shots of imaginary creatures. I wondered if I’d left my mind somewhere back on deck. I climbed down, trying not to look, because I was afraid even though I was dying to look at her again, at the…mermaid. Mermaid! What was it the White Queen told Alice? That she should try to believe six impossible things every morning before breakfast? Geez, Louise, a mermaid. This I had to see.

“The

nightingale tells his fairy tale

of paradise where roses grew.” Artie Shaw sings Stardust on your Lucky Strike

Hit Parade.

I reached the waterline where the ladder trailed into the ocean and where Jimmy held onto the rope, his legs under, treading water with lazy slowness. His left arm was around her shoulders now; he spoke into her ear as she watched me draw closer. Her smile was dazzling. Jimmy looked up at me clinging to the rope ladder just above him.

“Come on down, city boy.” Jimmy said. “The lady wants to give you something.”

I moved down another rung and held on, just slightly higher than Jimmy, letting my feet touch into the water with a wince. I really couldn’t swim and this much ocean, wide and open, made me nervous. I looked at the woman; her graceful hands were empty and she sure as hell didn’t have pockets.

“Uh…” I said, short on vocabulary just then. “Give me what?”

Jimmy’s grin was bright enough to light one of the buoys he tended.

“Ka’ahupahau wants to give you the kiss, she says.” Jimmy said. Naturally I lost my grip on the ladder. With a ripple and muscular movement underwater, the woman flipped up into the air like a gymnast and grasped the higher ropes, her head even with mine as she caught and steadied me against the hull, placing my hands back onto the ladder. She was close now and I could smell her, a briny scent like a beach at sunset, and feel the slippery wet texture of her skin. Inches from my face, she stared into my eyes and I froze, motionless, caught in the gaze of something impossible.

The weight of years uncounted was in her eyes, smiling though they were, and something sad and far away seemed just beyond those black depths. Her dark hair was wet and trailing loose across her shoulders, with tiny shells of pink and what looked like white pearls woven throughout. She looked at me and then slowly, like a lioness waking up in the sun, powerful and beautiful and strange, she shook her head, and the shells tinkled musically against the pearls. She turned out towards the expanse of ocean and whistled two long notes. A loud splash came from about fifty yards out, then silence.

She turned to Jimmy and said something, a quick riff of that singsong dialect. He raised his eyebrows and then looked me up and down, appraising. Nearly naked, in just those damn silk boxers, it felt pretty intimidating, I can tell you.

“What?” I blurted out.

“She says she can’t kiss you. She says you’re the other kind.” Jimmy said enigmatically.

“What other kind?” I asked, bewildered. Jimmy shrugged, his face expressionless.

“It’s okay, it happens sometimes. She called her brother.” Jimmy said.

“Her what? You mean there are more out here? More of…them?” I demanded, looking around at the undisturbed ocean in confusion.

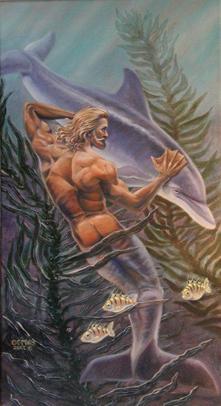

And just then, the water at my feet broke smoothly and a man leaped up to catch the rope ladder. He hauled himself up, out of the water, until his chest was even with mine. He shook his head like a dog, showering me with glittering droplets, and then turned to look directly into my face, now just inches from his. His coal black eyes were enormous, his nose long and straight, his lips thick and sensual; his breath smelled like sunshine. This was no fish girl. This was the most magnificent man I had ever laid eyes on. He grinned at me, showing teeth that were even and white. Then his lower body flipped up in the low water and slapped my legs with a silvery fluke.

This time I did let go of the ropes. Jesus, he was a fish, too!

He caught me as I fell and wrapped his arms around me as we went under and into the cold water, his body sleek against mine, solid with muscle. We came up with me sputtering, both of us wet, him pulling me up and back onto the ladder. I clung without thinking, to him, to the ropes, to anything, half-blind and coughing for breath. I could feel his chest hard against mine, his belly smooth and flat against my wet boxers and beneath that…beneath that his heavy body curved into the slippery tail against my legs.

He was staring into me again with those deep black eyes. His hair was darker than his sister’s, a rough jet-black cloud that massed around his shoulders like the mane of a big cat, tangled into it were shells and what looked like colorful seaweed. A row of shark’s teeth tied to a leather thong hung around his neck and he was just as naked as his sister. Even more naked, it seemed like, because this particular man was tight against me and I could feel the unmistakable heat from his body. Goosebumps rose across my arms and I shivered. He pulled me closer.

“His name’s Kahi’uka.” Jimmy said in a distant voice that was entirely too calm. “He’s her brother. He’s come to give you your kiss.”

I was suddenly very, very conscious of the strong arms around me, and the length of him hot and wet against me. Kahi’uka. For some reason, I was trying to spell that name. And failing, still shivering but no longer cold. I could feel his heartbeat, rapid against my chest. His intense eyes were a midnight sky with points of light in them like stars.

“Um.” I said, higher brain not functioning, my eyes on Kahi’uka. I just couldn’t make any other sound come out of my mouth. Jimmy’s friend was watching us, her arms around the C.O. and his around both her and the lower rungs of the ladder. They were both watching pretty closely. I swallowed hard. And then I forgot about them.

Because Kahi’uka kissed me.

“Sometimes I wonder

why I spend

the lonely nights dreaming of a song. The melody haunts my reverie

and I am once again with you.”… Lucky Strike brings you all the top hits of

1941.

If you’d told me I’d be getting the kiss of a lifetime right smack out in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, I’d have called you a liar. But that’s what happened. Kahi’uka had his arm tight around me, his muscles taut as cables, and that’s the only reason I didn’t just fall into the drink again and drown. His lips were on mine and they were somehow softer than I expected, lush and warm, opening up into the moist heat of his mouth as we kissed. I must have tightened up at first, tensed in shock, because then I felt it all go out of me as he kissed me, I felt myself loosen up and go limp. I think I closed my eyes. I know I moaned, a low sound from deep in my throat.

Kahi’uka smelled fresh and crisp, like a breath of clean ocean air at sunrise. Not fishy. Not a fish. Not this man crushed hard against me, mouth locked on mine. No fish this, this was a man; there was no doubt in my mind, none whatsoever, tail or no tail. I felt myself relax against him, and into his body, one hand wrapping around his torso to crush him closer, if that were possible. His mouth seemed to be pulling at me, pulling something electric out from me, heat threading from my fingertips, through my veins and into him, his lips drawing fire from my center outward until our mouths together were a shower of sparks, a brilliant sun exploding.

There was the taste of salt on my tongue as he withdrew, just the barest fraction of an inch away but it felt like too far; there came an inarticulate sound of protest, was it my voice? No knowing, no knowing anything while looking at his midnight eyes and his luscious lips, parted from our kiss and glistening. And yet, I did know something. Something had changed, felt different, inside me. Believe six impossible things before breakfast, indeed! And believing something impossible was easier than I would’ve ever imagined when that impossible something was this man, this Kahi’uka. I felt something inside my chest, something long ago grown over and hardened, crack open right then as I looked into the oceans of his eyes. I know its corny but something opened up like a flower in sunshine out there in the Pacific that day. Call me crazy. I think it was my heart.

Ka’ahupahau laughed, her silvery voice like little bells. It startled me and I jerked like I’d been slapped out of a trance. Her brother released me and I sagged against the rope ladder, suddenly weak. The air felt cold without the heat of his warm, wet body against mine and I shuddered, bereft. Kahi’uka smiled at me, right hand still curled through the ropes, and he reached out to brush the fingers of his left hand across my chest, moving in a deliciously slow pattern. But his sister laughed again, and this time Kahi’uka laughed with her, his eyes still on mine, his rumbling baritone a counterpoint to her rippling shivers of sound.

Kahi’uka looked over his shoulder at her, reluctantly it seemed, and then back at me. He grinned, white teeth lighting up his face, and thumped his lower body (his tail!) against the hull of the ship, twice. Half a dozen or more shapes lifted up out of the shallow waves and I got a quick glimpse of many heads of dark hair and bright eyes as they chirruped at the two alongside the ship, then, in unison, they all flipped up and dove deep, their silvery flukes catching the last of the sunshine as they disappeared. Ka’ahupahau called out, singsong and swift, to her brother. With a supple, muscular, twist, both their bodies launched out through the air and then sliced cleanly into the water.

They were gone.

I stared at the spot where Kahi’uka had vanished; my left arm still curled around the ropes, until Jimmy tapped my shoulder and began to climb the ladder. I could hear the crew talking above us, and then a riff of laughter. Sounds of the ship, of the ocean itself, blotted out in the last few minutes, came back into my awareness. As did my state of dress and, startled, I looked down at myself. And blushed like a bride. All I’ve got to say is that soaking wet red silk boxers leave absolutely nothing to the imagination.

The crew didn’t say much to me and I didn’t have much to say to them either. Up on deck, they watched me and I wondered, wondered how many of them had fishy friends and whether I was flat out crazy. I couldn’t get that last vision out of my head, of Kahi’uka disappearing into the deep blue sea and all those others with him. How many had there been? Where had they gone? And why didn’t anyone else know about this, how could they keep it so quiet…and why?

Then I thought again of Kahi’uka’s eyes, the feel of his lips on mine and the salt scents of the sea on his wet body. Would I tell? Not that anyone would believe me but wasn’t there something about this that I wanted to keep close to my heart, keep secret inside me? There was, yes, but warring with that was every journalistic bone in my body, screaming for my camera, for a one-of-a-kind photo spread in a glossy high-end news magazine. With my byline.

With a frown on my face and a Class-A headache boring it’s way into my skull, I made my way to the mess, smiling a whole lot less than I usually did on a job. When I stood, tray in hand, I saw Jimmy waving me over to his table where he sat deep in conversation with the ship’s mate. I joined them without speaking; not even noticing whatever it was that I shoved into my mouth and not joining into the conversation, fascinating though the routine naval directives and charts were. We were due to reach Long Dock at Midway that night, 28 degrees north latitude and 177 degrees west longitude, just east of the International Date Line. Tanks were low, but the captain said we’d refuel back in Honolulu after this run, as usual. The same old boring nothing happening out here at the end of the earth, it seemed, buoy duty and search-and-rescue detail, despite the far-away war in Europe. And not a word about the strange events earlier, nothing different on the faces around me, so what could I say? I had a hell of a lot to think about, that’s for sure.

This was the night of December 6th, 1941.

Back in my bunk, I found I couldn’t sleep but not because of any damn ghostly lovelorn sailor in the cabin. I pulled on my shoes and made my way out to the deck on a moored ship gone night quiet, to smoke and watch the starlit waves. If I was watching for something else, I wasn’t admitting it to myself. The sound of the water began to make me sleepy, those low waves stroking rhythmically against the hull. Even the distant voices of men on duty and, much further away, the men ashore, faded away as I stood there, my eyes moving lazily, sleepily, restlessly, across the water. Trying to imagine what lay under the soothing, endlessly moving, dark surface of the Midway harbor.

That’s when I heard the singing.

Far off and eerie, the gentle music seemed to float over the water to me in the darkness, a soft ocean breeze of sound. Drowsy, I didn’t think it strange at first, just arresting, catching and focusing all of my attention onto a melody that seemed familiar yet somehow I couldn’t think what it was. Maybe it was more that the song seemed so natural, seemed as basic as the movement of the water, primeval, as if remembered from another life, long long ago. Like some distant thing calling, pulling at me, calling me, who couldn’t swim, calling me out to sea. I caught myself humming along with it and stood up straighter, looking out across the waves. Because there was no question of the song coming from somewhere aboard, the source was…out there.

But there was nothing out there except the ocean and the midnight Long Dock marina and the moonlight. I heard the song, somehow closer now and, as God is my witness, I don’t know what made me find the rope ladder that night. I know I couldn’t help myself, could no more have stopped myself kicking off my shoes and climbing down to the water than I could’ve stopped breathing. Those voices, light high voices like birds, low voices like some deep-sea creatures come awake, woven together in a song that whispered through the air like the moonlight itself, beautiful and mysterious and not of the waking world. Whatever fear of drowning I owned was forgotten right then, as my feet touched into the shadowy water. I clung to the ladder in my cotton pajamas, mesmerized, straining my whole body to listen. The song was bewitching, rising gently up and down in that lovely melody, the voices singing of things secret and silent, of strange places far away and fathoms deep, of sinewy swimming beasts from the time before the dinosaurs. Whether I was awake right then or asleep, I couldn’t have told you.

And then I saw him. Kahi’uka.

The instant I saw him, I knew it was for him that I’d come down there, that I’d come out of my cabin and climbed down to the water. He broke the surface smoothly, silently, and barely five feet out from the hull, then seemed to float effortlessly in that one spot, watching me. As he watched me, he opened his mouth to join the chorus and I knew that his voice had been part of it all along, part of the haunting harmony that drifted across the dark waters. I stretched out my hand towards him without speaking. And he came to me, riding along the top of the waters that moved silently aside for him, his face never under the water; he continued to sing. When he reached the hull, he held up his hands to me and I, with no thought whatsoever of drowning or depths, let go. I simply let go of the ladder, the only thing that held me up out of the harbor, and dropped down into his waiting arms with a quiet splash that quickly died in the night.

The only sound now was the eerie singing, from somewhere across the water and from his own mouth even as he smiled at me. Singing, singing, a choir of seaweed angels, it seemed, and singing just for me. His arms tight around me, holding me against his sleek and muscled body, he touched his lips to mine and kissed me slowly, deeply. His mouth was hot in the cool night and, as he held me, the salt water that soaked into my thin pajamas somehow didn’t make me shiver. He was heating me with his body, with his mouth, his tongue, with his kisses, and it seemed as if he was still singing, even with his mouth on mine, but the singing was now invading my whole body, electrifying me down to my fingertips and toes. I wrapped myself around him and held on, not so much for fear of drowning as for the pleasure it gave me, the satisfying feeling of animal closeness. He tightened his grip and, without releasing me from the kiss, his lips pressed against mine, he twisted his body and dove deep into the harbor’s dark water, taking me with him beneath the waves.

I must have forgotten to breathe, I must have been shocked, too shocked to try to take in air. But what I remember is that I didn’t want to breathe, didn’t feel the need for air with his mouth on mine, as our bodies moved together through the dense, dark underwater realm. He was directing us, pushing against the water with his great heavy tail, his lips on mine, kissing me, kissing me and taking us both somewhere, as smooth as dreams. Schools of slick tiny fish brushed my skin, plants unknown and uncataloged made dark patterns beneath us as we swam. Dim light filtered down, the moon kissing the ocean, for we had surely left the harbor, but I don’t remember feeling fear. I held tighter to him than I’d ever held to anything or anyone but my thoughts weren’t on the ocean floor below us or on the distance we were traveling. My thoughts were on him and him alone. Kahi’uka. It was as if I was asleep and dreaming, but I had never been more awake, more electrically alive, in all my life. The feel of the water against my flesh was almost erotic, waking up every nerve in my body as we slipped through the depths to our destiny.

“We’re dancing in the dark and it soon ends; time hurries by, we’re here and we’re gone…”… music all through the night with your Lucky Strike Hit Parade, bringing you the lush sounds of Frankie Sinatra.

He brought us up and broke the surface, treading his strong tail beneath and between my legs, keeping us in place as I gasped and coughed, finally aware of a need for air. I sucked in huge lungfuls, still holding close to him, my pajamas bunched thick with water against my skin. Finally, when I was breathing evenly, I realized the music was still there and much, much nearer, but Kahi’uka wasn’t singing. He was watching me. When I met his eyes, he laughed aloud and shook his head, droplets spraying and tiny seashells moving in the thick mane of hair. Above us, the moon was out and very white, shining down on what looked like a lagoon with dark shapes of trees hanging over the water’s edge, trailing mossy growth into it. He pulled us through the water, across the top, thrusts of his powerful tail supporting us both, as he drew us onto the shore.

If it was cold, I didn’t know it, if it was late, I’d forgotten. Looking into Kahi’uka’s eyes, I could feel nothing more or less than absolutely at peace with everything under the sky. Whatever fears I might have had seemed to melt like mist this near to him, a man so sure, so strange and yet as natural as the night itself. I really don’t think I was entirely awake, or maybe it’s more true to say that the parts of me that were awake were ancient, primal, and far less dependent on logic or thought. I was operating on prehistoric instinct, something deep inside me recognizing patterns that my conscious, everyday mind had no need of. And that instinct had brought me to Kahi’uka…and him to me, it seemed.

He pushed me up onto the shore and, with a shove against sand of the shallows, placed himself alongside me, the tip of his gorgeous tail still underwater as he lay back. He turned to look at me, as if to ask for my attention, and grinned when he saw that I was already looking at him. I smiled back. Oh, kid, how can I make you understand how beautiful he was that night, an exotic and gypsy elegance; the moonlight burnishing his wet skin into gleaming platinum, his black hair wild and long and tangled with shells, a shark’s ragged teeth around his neck, his eyes shining as he looked at me more hungrily than I have ever been looked at in all my life, before or since. He reached out to touch me, fingering the sodden clothes and then pulling at the buttons. Not a bad idea, I thought, unbuttoning the shirt and pushing off the pajama pants, then looking about for someplace where they could hang to dry. Then I stopped myself and laughed. If I was going back to the ship, they’d sure enough get wet again, so I just tossed them aside into the sand and turned back to Kahi’uka. And then hesitated, how to speak to a dream?

Oh, but I was awake and I knew it.

“Kahi’uka?” I said, stumbling over the foreign sounds of his name. He smiled, white toothed and happy. He said something in that rippling musical dialect and shook his head. He took my hand in his and held it, pulling me closer. I’d never felt gritty sand against my naked skin before and you’d think it’d be uncomfortable but, if it was, I didn’t know it. The singing had died away to a soft, sighing that might have been the wind, except I knew it wasn’t. Where were the other ones, the other ones like him, the ones still singing to the skies? I could see no one on the lagoon shore but the two of us, lit by the wide full moon overhead. Alone with him, he seemed far less fantastical, more solid and part of the world around us, a purely natural being, grounded in the very sea and earth. The look of him, dark and beautiful and strong, the smell of him, sweet and briny and fresh as the wind, was intoxicating; he filled up all my senses as he stroked his hands across my body, urging me against his own, coaxing fire from me by friction.

Now, I’d been with a lot of men by that time, don’t think I hadn’t. Back then, men didn’t talk about things the way you kids do today but we did it all, just the same. And I’d had plenty of friends; some were very special friends. But nothing, nothing at all, prepared me for how the slightest touch of his fingers felt along my flesh, both of us wet, newborn from the salty depths like Venus, and lying naked on that north Pacific shore. I felt so damn free, cast up on the sand there with him, with no mark of civilization on either of us, just two men, two bodies under the goddess moon.

Whatever I had been before Kahi’uka was nothing; that night I was myself, my very self, my true self, my self of possibility, stripped bare under ancient stars and whatever forces ruled those heavens. And that’s how I met his touch that night, with all of me, with parts of me that had never before risen to the surface, no longer pinned under layers of modern living, and with my whole entire and aching heart. His silken lips on my skin, his rough hands, his body stroking and shuddering and forcing me down in the sand until it ought to have hurt but, oh God, it didn’t; his was a thing I’d never imagined, never thought to experience, never had even known enough to feel the lack of with anyone else before Kahi’uka. Never before but my body knew him, recognized a heart’s touch, knew the feel of ancient urges and primal mating calls enough to light the fire and hand it over, precious flame, to share together, back and forth between us, a sacred heat that seared our skins.

And so he had me there that night and I had him, our bodies couched in moonlit sand, on the shore of that lagoon at the far end of the world. But, kid, if you think I’m going to tell you all of it, of how and where he touched me, draw you a diagram of parts and pieces, fitting them like jigsaws, you are very much mistaken. Some things are best kept private; some things are best kept close, some things are better wound safe inside a seashell heart, filling those twisting iridescent corridors with living breathing flesh, his and mine. That memory isn’t for you and no, I’m not gonna let you look.

But if you think that because this man was something else, of strange and sea bred flesh, that he was not a man, well you can think again. He was a man in every way, in all the ways, a primal male, a force of nature. Yeah, he was a man, I’ll tell you that much, he was a man among men and so much better than the rest. I slept in his arms that night, exhausted and curled together with him in the sand, feeling no chill and knowing no dreams that I could remember after waking. I often think of that, looking back and wondering whether I had dreamed, if a message had been sent and somehow forgotten in all that happened after. As if there must have been, should have been, a warning from the heavens.

That night, I gave him more than just my body, I gave him everything I had and then I kept on giving, finding such pleasure in that gift and the giving that I kept nothing back so that, amid all that easy giving, I handed him my young heart without a moment’s thought. Don’t mistake that, I want that clear, I loved him, there and then beneath the stars and ever after, always; I gave my self, my heart, and yes, just that once so long ago but, like they say, kid, once can be enough. And when he whispered in my ears, his breath like a caress, his words mysterious but his meaning clear, I knew that Kahi’uka loved me too, knew why we’d met, drawn together by his people’s dreams. It was something meant and if that’s too vague for you-if destiny is something you deny-then I can’t make you understand what that night meant to me, and just how much it mattered. Maybe I’m just a crazy old man. Believe what you want, you kids always do.

“In dreams, I seem to hold you, to find you and enfold you, our lips meet and our hearts, too, with a thrill so sublime…”…Jimmy Dorsey sings Green Eyes on your all night Lucky Strike Hit Parade. Smoke Lucky Strike-It’s Toasted!

I woke to daylight and the shrill shrieking of ship klaxons.

Kahi’uka was gone; I was alone on the shore of Midway Lagoon. I stood and struggled into my damp pajamas, staring goggle-eyed at the unexpected and inexplicable sight of the USCGC Walnut, all 885 tons of her half-filling the lagoon itself, twin propellers churning up the water as she hove about, lights flashing stern and aft, her attack sirens ripping the air and sending tropical birds up from the treetops that ringed the natural harbor. As I pulled up my pants, I looked out the lagoon mouth and into the Pacific Ocean. If the light and noise and sudden appearance of the Walnut had galvanized me, what I saw there froze me in my tracks.

A nearly two-thousand-ton Akatsuki-class destroyer of the Teikoku Keigun, the Japanese Imperial Navy, flanked by two Nagara cruisers and less than ten thousand yards out, filled the horizon and blocked the sun. This was December 7th of ‘41 and, though I didn’t know it right then, this was the day the Japs decided to conquer the world. As I watched the destroyer, unable to move, two enormous fore-mounted steel turrets began to slowly rise in a majestic ballet of death, smoothly aligning themselves toward the Walnut, still desperately turning about. Above the turrets, on the forecastle, Jap flags whipped their hurrahs in the ocean wind.

When the first mortar shells hit, rending the air with noise, dirt and water sprayed up in screaming fountains around me. I hit the ground, belly down in the sand. Then the cruisers cut loose, their lighter ordinance still heavy enough to tear up the shoreline and the hull of the Walnut as gunners began to make their target. The 50-pounders thundered again and a mortar slammed down hard behind me, shaking the earth with a Jurassic roar of noise and power, coating me with sand and leaves. What the Sam Hill was I doing out here in my pajamas with a battle going on right in front of me, and why the goddam hell hadn’t I ever learned how to swim? Even if I had, could I’ve made it to the ship in all this? I didn’t think so, not really. Staring out onto the lagoon, I didn’t once think of my camera; all I could think about were the guys onboard the Walnut: baby-faced Billy, dark Irish Sean and Captain Newsom-Jimmy with the sun gold hair. And then I remembered.

The USCGC Walnut was unarmed; she carried nothing heavier than the four 20mm Oerlikons mounted fore and aft and a couple lousy anti-sub depth charge tracks. And there were four thousand tons of Imperial war machine sitting at the mouth of the lagoon. Oh, Christ. I closed my eyes in prayer.

Shells boomed around me, exploding in the air and on the ground, and the smaller fire rattling alongside never seemed to stop, just went on and on between the thunder and distant muzzle flash of lightening. The Walnut had finished its turn maneuver, now presenting fore to her enemies, Oerlikon machine guns chattering but falling short. From where I hugged the ground, I could see sailors running on deck, search-and-rescue rifles slung over their shoulders. Occasionally one would kneel and fire out to sea, succumbing to that hopeless human need to offer some resistance, no matter how ineffective. I began to crawl for cover, useless as that probably was, I just couldn’t help myself and ended up behind the nearest tree. Looking at its fragile trunk, I wondered who or what I was fooling.Just what the hell were Japs doing at Midway? There was nothing worth much here and even I knew it. The only other ships that came through here were merchantmen or supply ships, and we were just too far east from Japan for any reason that made sense to me. After all those Jap attack scares along the California coast last year, I had to wonder if those people were right after all. It had seemed so crazy, so unlikely, but here they were, the damn lousy Japs, bigger than life and so much closer than they ought to be. Then I got a really crazy thought. If the Japs were here, where else were they today? But that flat out wasn’t possible.

And anyway, the here and now, is what I had to concentrate on. For an agonizing second, I thought of Kahi’uka but just as quickly relaxed. His people disappeared the minute all the noise started, no question. After all, its what I’d have done, if I’d had the chance. This wasn’t the duty I’d signed on for. But then, couldn’t anybody say that? Who the hell ever does really sign on for war? If you’d told me then I’d end up signing on within a year, I’d have called you a liar. Right then, hiding behind a tree in a storm of mortar shells, I had all the war I could stomach, and then some.

I ducked down involuntarily as a shell screamed through the air above me, shredding trees with impotent fury, leaves and bark showering over me. I felt like such a coward huddled here on the ground, shaking harder than the trees and surely only seconds away from crying like a baby. If I’d ever been this scared before, I’ve forgotten it completely. Maybe when I was tiny and nightmare things invaded my sleep but, then, isn’t that what this was, right now? If this wasn’t a goddam nightmare, I didn’t know what the hell one was. Bursting mortar shells and pounding guns and somewhere there was the sound of screaming. I only hoped it wasn’t me.

I ignored the whistling sound at first; the air was full of whistling sounds and a whole lot worse, so I didn’t look up. Then a single loud, piercing whistle forced me to look up and, when I saw someone at the waterline, I jumped up before I could think. Kahi’uka! But it wasn’t him. His sister, Ka’ahupahau and two others, none of them my Kahi’uka, were swimming out a few feet from shore, all treading in the water effortlessly just as if the world wasn’t exploding, and watching for me in the trees. I came out from behind my ridiculous shelter, more a thing of emotion than reality since it was just a tree trunk, and walked back to the water, trying not to look out at the Jap destroyer. Of course, I looked. And then grinned like a fool!

Swarming above the Jap ships like horseflies were a handful of PBY Catalinas; those wonderful Navy Flying Boats, really patrol planes, yanno, amphibians, they can land on water. Bullet tracers stung the big ships, the Navy planes dodging in and out of the ineffectual Japanese ack-ack guns and coming back for more. Damn, just seeing those Cats up there made me proud to be American. Corny, but true. The only thing was, those little planes, or even the Walnut, had nothing on those Jap ships; they were gnats biting a bunch of elephants. And I had a feeling I wasn’t the only one who knew it.

Ka’ahupahau came up closer when I knelt down at the shoreline; she looked tired. They all looked tired, their faces gaunt, dark circles under their gleaming eyes. She took my hand in her smaller one and pulled it to her lips, kissed me on the palm, making me blush. The others watched, one of them, a handsome young boy with dimples, of all things, smiled at me but it was such a tired smile. They didn’t seem surprised to find me here; I wondered what they knew about last night. And wondered where Kahi’uka was, but wasn’t sure how to ask. Well, nothing ventured.

“Kahi’uka?” I asked his sister, “Where’s Kahi’uka?”

She shook her head, pointed to one of the Jap ships and said something in that singsong lingo that, naturally, I didn’t catch. Then she held up an army-green backpack out of the water, as if showing me could make me understand. Well, I didn’t understand but sure couldn’t see why she had a pack like that or what the bulging shapes inside it were. I touched its webbing, looked at her for permission, and then untied the top to look in as she watched patiently. Which didn’t leave me any more informed, I had no idea what those flat metal disks inside were, they seemed heavy. I looked around, they all seemed to have these packs, holding them under the water or hooking them over their shoulder. I frowned. These looked like military packs, where’d they come from? And how’d her people get them?Some journalistic instinct made me lift one of the disks out and examine it. I held it up with difficulty, it was even heavier than it looked and there were two others in the pack. I wondered how Ka’ahupahau managed, maybe the water made it easier or maybe she was stronger than she looked. I examined the disk, turning it over in my hands. The stenciled markings on the underside caught me up short, a serial number and words…words that made my stomach suddenly feel like solid ice.

Property United States Navy UDT.

The disk suddenly felt ten times as heavy, now I had a feeling I knew what it was, even though I’d never seen one. UDT stood for Underwater Demolition Teams, that much I knew from scuttlebutt. I’d heard about research and missions, all top secret, but the brass always denied everything in the press, called it baseless civilian rumors. Well, I wasn’t holding a goddam rumor in my hand and looking at who knew how many others in all these packs. Shit!

I’d met a guy once in a bar, dishonorably discharged he said, who’d volunteered for ‘extra hazardous duty’ when he signed on with the Navy. What the ‘extra hazardous’ turned out to be was with something called Seals, some hush-hush group that recruited guys who could swim real well and didn’t much mind handling hair-trigger explosives underwater. I looked at Ka’ahupahau and the others, at their exhausted faces and silvery tails visible just beneath the lagoon surface. I guess you could say they swam well… like fish, in fact. I looked where Ka’ahupahau was pointing, out at the damn Japs. Kahi’uka? Oh, Christ, no.

I hated the Navy more in that second than I ever had before, and I’d never been much of a fan.

“Kahi’uka, where’s Kahi’uka?” I asked his sister urgently. Hell, I wished I spoke whatever it was they spoke. I needed to get to the ship, get to Jimmy, who could speak it, could talk to them for me. My heart was thumping in my chest. Where was Kahi’uka? I didn’t want him doing this. Right here in my hands and in front of me were more explosives than I cared to think about. I also didn’t want to think about what they were doing with them. Oh, Christ. This wasn’t their war, hell; it wasn’t even my war, not back then. I looked at Ka’ahupahau helplessly and gestured to the ship. But I think she understood. She was frowning at me, and then shook her head emphatically.

“Yes! Yes! I need to get to the ship, dammit!” I yelled, I think I even stomped my foot. I hated that I couldn’t talk to them, couldn’t swim, couldn’t get to the ship without help and there was no knowing when the crew would see me. Or even if the Walnut would still be here when the Japs were done. Behind me another shell hit and exploded, tearing up the tree line and throwing up dirt and greenery onto all of us. That seemed to decide her. She nodded and snapped her fingers at the dimpled boy who treaded water a few yards out. He looked at her as she rattled off a string of liquid syllables, his eyes intent. He nodded, handing his pack to the man next to him, and flipped neatly up into the air and dove down, his delicate fluke catching sunlight before it disappeared.

In a rush of moving water, he broke the surface beside me, coming up clean and smooth to slip one arm around my waist. I looked at him, surprised. He grinned at me and I swear he looked like any other kid; he looked terribly young and awfully cute, his chest flat and slender as any other teenage boy’s. Under the water, against my legs, I could feel his tail, twitching against my leg as if he were eager to be off. I smiled back at him and wondered what his name was. Still smiling at me, he very deliberately took a deep breath and held it, gesturing to me to do the same. I filled my lungs as he wrapped his arms around me, his body surprisingly slight but perhaps only slight compared to Kahi’uka. And thinking of him, I closed my eyes just as this boy twisted and launched his deceptively powerful body out and into the cool lagoon, taking me with him under the water.

I hardly had time to realize we were under before we weren’t, coming up sputtering and nearer to the Walnut. But not near enough. I opened my mouth to protest…and to breathe…but before I could say a word, I heard it. Far overhead, I heard a screaming, the sound of a huge object displacing air was unmistakable. I looked up but it wasn’t another shell, something big was falling fast. One of the Cats was hurtling to earth from right above me. The panic I’d felt earlier, and still felt, ratcheted up a few notches into flat out terror. Kahi’uka! My heart beat so fast it hurt inside my chest. Holding me close and treading water, his face impassive, the boy put his left hand over my mouth and I closed it involuntarily. And then he dove again, taking us back under.

Even underwater, the impact was incredible. The plane hit down hard, shaking the earth beneath us and throwing deep shock waves through the lagoon. We came up at the farther shore, me gasping for air because my lungs were empty and the boy pulling me up out of the water and onto the sand. I stood up and saw the beach here had just been destroyed, almost flattened, leaves and dirt were still hanging in the air, settling slowly downward, and the air itself was hot. In front of me, the trees had been torn apart in a short path that ended maybe twenty yards ahead.

Ended in the crushed, smoking heap of a downed PBY-Catalina, her wings like crumpled tin foil. I turned to the boy but he was gone, the tip of his tail sliding underwater as I watched. I looked back at the downed plane and exhaled hard. Now I may not seem like the brave type to you and I sure didn’t feel like it right then but I walked through the smoking trees, barefoot in my wet pajamas, to see if I could help anyone out of the burning wreck.

Just then, as I turned my back to the water and the battling ships, the whole entire lagoon exploded behind me, the noise like an ice pick through my eardrums, leaving me deaf, with no sound but a humming in my head. The wind and wave hit seconds later and threw me to the ground, flat on my face once again in the sandy dirt. My head spinning, I struggled to my feet and looked dumbly, unable to hear a thing, out over the heaving, roiling water that now covered my feet where I stood. The Walnut was still there, heaving as her engines worked to stabilize her in water gone wild, but further out, past the mouth of the lagoon, something had changed. It was hard to think with the silence that hummed in my head and I couldn’t quite make out what had happened. Finally, dully, I realized that those two Jap cruisers that lay just out from the island were now flanking nothing but burning debris and a rapidly sinking hull.

The massive two-thousand-ton Akatsuki-class destroyer of the Teikoku Keigun…was gone. Gone. It all seemed so unreal, like a picture of something far away, and I couldn’t get my eyes or brain to clear, couldn’t seem to take it in. As I watched from the far shore, the Walnut opened fire on the cruisers with all four 20mm guns but even I could see that the Japs were busy pulling the Emperor’s sailors, those that were left, out of the drink. Shells were still launching from the Japs, and though I couldn’t hear them, I could see where they were hitting the island and the water…but thankfully missing the USCGC Walnut. I finally turned back to the wreck of the Cat.

Well, I won’t bore you with all the details but the Walnut sent their small boat and we got all seven of the Cat crew out, only two of them hurt bad, which seemed like a minor miracle to me. During the rescue, I must have forgotten to be scared, forgotten to track the shells and thunder, caught up in what we were doing and trapped inside my useless, stunned ears, because when we were done, when we started to ferry everyone back to the Walnut, it was already all over. The cruisers were gone, the ocean outside the lagoon littered with smoking wreckage. No sailors, no ships. Just the Walnut herself and me back aboard, grudgingly okayed by the medic and sent off to my cabin with orders to sleep. I kept asking to see Jimmy, but whatever was in the shot they gave me finally made me woozy enough to obey orders and hit the sack.

When I woke up, we were halfway to Honolulu. We were also at war with Japan. The attack at Midway had been nothing, just a single turn in their choreographed conquering dance across the entire Pacific Ocean.

I could hear a little, and that was something. I hadn’t been sure the damage wasn’t permanent, despite what the medic tried to tell me. I finally cornered Jimmy in his cabin two hours later and something in my face must have told him I wasn’t gonna be put off because he sat just still and listened while I talked. I was pretty angry, I admit it, and I wasn’t all that nice. My language was on the colorful side and probably not what a Coast Guard captain was used to taking from a civilian. I told him what I’d found in the packs, told him what I thought the damn Navy was up to, demanded to know what the hell was going on. When I was finished, he just sat there looking at me, the expression on his handsome face unreadable.

“Johnny, this stuff you’re asking about, it’s classified.” Jimmy said quietly. At my indignant look, he waved his hand in the air, dismissively. “It’s classified but that doesn’t mean I’m not gonna answer you, or answer some of it, but not because the Guard would want me to. What I’ll tell you is for you, because Ka’ahupahau trusts you, but you can’t repeat it, and you have to swear you won’t. I could lose my commission; we could both go to prison. Are you hearing me, Johnny?”

I nodded, tight-lipped, too angry to say anything else. He studied my face for a moment, then spoke, his voice quiet.

“You’re not wrong, I’ll tell you that much right off, Johnny. Yes, the Navy’s using Ka’ahupahau, that’s how we met her people but that’s a long story and beside the point. The thing is, some stateside fancy-pants got the idea from an old report he found back in OSS records and contacted the Navy, who ordered the Guard to find these people. And the Guard did find them, nearly two years ago. And, well, there’s a new program that’s supposed to be secret but I guess I’m not surprised a journalist has heard of it, I never have had much faith in all that cloak and dagger stuff. At first, I’m told, they just used good swimmers but when they found Ka’ahupahau and her people, well…’good swimmers’ took on a whole new meaning, I guess.” Jimmy looked sad, sad and tired and a little bit old. “Plus, of course, the Navy likes the idea of…expendable personnel. People that nobody, nobody on land anyhow, would miss or even know about if they died.” Jimmy sighed and closed his eyes. “More secrets. Lives that don’t count.” He opened his eyes and looked at me.

I stared at him. I think I’d been expecting him to deny it or to somehow prove it wasn’t true, offer me some other explanation. But there was something else; some awful worry poking at the back of my mind. Something almost too terrible to ask about. I opened my mouth, and then closed it again. Ask me no questions, I’ll tell you no lies. But I didn’t have to ask, Jimmy knew what I was thinking, of course. Probably knew what I was feeling, too. He shook his head sadly, without meeting my eyes, and spoke the name I was trying not to say.

“Kahi’uka was one of the ones who attached the explosives along the Jap destroyer’s hull, Johnny. After they hit Pearl, the Navy issued orders to stay put…we were a Decoy, supposed to lure the Japs away from vital targets.” I just looked at him, my anger draining out of me at the look on Jimmy’s face.

“And? Kahi’uka, the others with him?” I asked him, my voice a whisper. He shook his head.

“Gone.” That one word sounded flat and cold, and somehow wholly inadequate to the situation. I got up without another word and left him sitting there alone in his little cabin. I hated him, I thought dully, but really I didn’t. I don’t know what I hated right then, whether it was war or the military mind or the world at large that could dismiss something so precious and so beautiful, could only think of its potential as a weapon.

I never saw Kahi’uka again.

Looking back, after the war and the filthy years I spent slogging through France, I think I’d say that all of us are seen that way by the military mind, as things to use, tools for a purpose, and every single one of us entirely expendable. That I lived through to VE Day has always struck me as just a comical coincidence. I lost a lot of buddies along the way and never noticed any of it making any difference. Young men covered in blood and crying for their mothers, mostly just kids, younger than you, mostly just boys but dying in the far-away mud like that, like nothing, like it wasn’t the goddam world coming to an end. For them, of course, it was. Death and death and more death, and all of us covered in filth and in a constant state of abject terror. Bravery doesn’t mean the same thing when you’ve been out there pissing yourself in the mud, those medals and things are just hunks of metal. Just a lot of sound and fury, signifying nothing. I don’t blame you kids for being against war, for refusing to fight or running off to Canada instead of to war. I’ve been there, I know. I know.

Well, that’s about all there is to tell, kid. The Navy arrested me and impounded my camera. Oh, yeah, I did get some pictures, of Ka’ahupahau and the others on the way back to Honolulu but I never had the chance to develop them. Who knows, maybe they didn’t turn out. The Navy kept me locked up for a few months, asking questions and checking my story, even bringing in the OSS, threatening me with life in prison if I published or even talked, but they never did charge me with anything and, finally, when they were sure they’d scared me enough to keep me quiet, they let me go home.

A week later, I joined the Army. I haven’t been to Hawaii or even near the Pacific Ocean since it happened, I don’t even visit the coast of California. Just thinking about it hurts too much. And I never did tell anyone this story, well not the whole story, not ‘til now. You’re really a good listener, yanno?

Listen, kid, I don’t want to talk any more, okay? I mean, thanks for the drinks and all but I gotta catch a plane. You understand, right? I need to go home. Thanks for listening to an old man and, ah…don’t take anything I said too seriously, okay? You seem like a nice kid. Maybe I’m just rambling. You got what you wanted? Fine, fine…just…

Want me to leave the tip? No? Okay, well…goodbye. Good luck, kid, have a nice life and, really…thanks for listening.-The End-

An afterward from TR:

Johnny, which wasn’t his real name, of course, left me then and caught his plane. Sudden, but I supposed we were done. I finished up my notes and stuffed them into my briefcase, still trying to work out what I thought of the story he’d just told me. I wasn’t sure I liked the ending but, well, that was the ending he gave me.

The only thing was, after I got up to leave, I passed by the gate where his plane was boarding and stopped to watch him waiting in line to board, a leather overnight case in his hand. I couldn’t help thinking he was a handsome man, despite his advanced age, tall and athletic looking, his hair gone white, his eyes a vibrant deep blue.

The stewardess finished boarding her passengers and fussily closed the access door. I turned to go, and then turned back sharply, my eye caught by the departure notice beside the gate.

‘American Airlines flight #3760 direct to Honolulu, Hawaii. It’s the destination, not the flight.’

Kind of makes you wonder, doesn’t it? Going home to Honolulu.

I dunno, maybe I’m just an incurable romantic. --TR

“Don’t sigh and gaze at me… people will say we’re in love.” Lucky Strike Hit Parade brings you all the songs you love.

Smoke Lucky Strike-It’s Toasted!

[This is a true story. This story is under copyright and legally protected against infringement. Events are presented exactly as told to me; only the names have been changed and any mistakes in transcription are my own. Read my other stories at www.tragicrabbit.org and www.awesomedude.org –Tragic Rabbit]

AMERICANA-REMEMBERING DECEMBER 7th, 1941

“It’s taps for the Japs since they bombed Pearl Harbor, it’s taps for the Japs since they pulled that boner, that Sunday morning on the isle of Oahu, will never be forgotten and they’ll soon be through; that flag of Japan with its rising sun, it soon will be set and their day is done. When Uncle Sam gets going, it really won’t take much, to stop their slant-eyed rollin’, they’ll say ‘scuzit’, ‘please’ and such; it’s taps for the Japs, they stuck their necks out, it’s taps for the Japs- the saps!” -Freddie Fisher and his Schnickelfritz Band, Decca Records

“The melody haunts my reverie and I am once again with you.”

Smoke Lucky Strike-It’s Toasted!