Squeezed

A Story in The Human Calculus

|

|

Three ink blots on the eastern map of Pennsylvania – between the Delaware and Susquehanna Rivers – represent three narrow valleys, covering together less than five hundred square miles, which produced every single ounce of the hundreds upon hundreds of millions of tons of highly prized, hard, pure, slow-and-hot-burning anthracite coal in America.

Alternating layers of rock and coal are piled one upon the other; layers of a cake, each thick layer of rock separated from the next by the thin sweet filling of a coal seam. The rock layers vary from a few feet to two hundred, the coal seam from a foot high to thirty and more.

The smallest valley, lying along a river’s north branch, is just four miles wide and twenty long, its geology so sharply defined that one could pass in five minutes through any notch in the surrounding mountain walls and find oneself as much out of the coal regions as if a hundred miles away.

This coal, sometimes is called Black Diamond it is so very hard and lustrous, almost gem-like; has the highest carbon content, the fewest impurities, the highest energy content of any coal, had powered much of the industrial might of a nation. Coal mining became the business of generations. Because the steel mills and the foundries, the railroads, the furnaces and the boiler rooms in the plants and schools and offices and homes of a nation had a voracious appetite; and because the collieries aimed to please, a coal miner’s life is a hard one.

Or so they say.

Breakers squat upon hillside and valley like enormous preying monsters, eating the sunshine, the grass, the green leaves. Dragon-like, smoke from their nostrils ravages the air, leaves scant surviving vegetation miserable, half-strangled. Along the ridgelines the rare silhouettes of a few unhappy trees etch themselves against moonlit clouds.

In murky moonlight a wisp of a boy walks quickly, arms tightly wrapped, threadbare coat insufficient against the penetrating chill of pending dawn.

A towering frame of blackened wood looms above, tipped in a curious little peak. Along its sides a profusion of windows at unexpected points offer glimpses of whirring machinery. A mighty gnashing tears at his ear. With terrible appetite the monster sits imperturbably munching coal, mammoth jaws grinding out a hellish, monotonous uproar.

This is Jack Murphy’s first day in the breaker.

He is nine. By the new mining laws it is no longer legal for a boy this young to work the mine. So he lied. He was, he said, “twelve, goin’ on thirteen.” He was well coached by other boys. The foreman knows he is lying – anyone could tell just to look at him – but the foreman does not care; he is not paid to care.

Jack’s alternative is legal work in the silk mills, legal from the age of 8, and he did work there for a bit. But the mills don’t pay as well and the future is limited; one cannot become a miner working in the mills.

The mills are for children and women. Men do mining.

Grimy black coal dust lies deep on any unmoving surface; clouds of it billow, darken the air. The crash and thunder of the machinery is like the roar of an immense and violent tempest. The very structure is a-tremble with the sweep and circle of ponderous machinery. It is a place of infernal din, the very sound of hell. Conversation is nearly impossible.

At the top, laborers dump an endless procession of cable-drawn coal carts into the voracious maw. Huge black boulders of coal, some half the size of a house, slide forward reluctantly, to begin their journey down through the building. Great teeth on massive revolving cylinders catch and chew them; breaking them apart, namesake to the structure. Broken, pulverized, coal slips through sizing grates, each lump into its proper chute, until finally the entire mass passes by in black streams of carefully sorted fragments, leaving alone the ubiquitous dust to mark its passage.

At one time breakers were built directly over the main shaft, so the coal could be hauled up directly into the breaker.

Up at the Avondale mine a fire in the shaft set the breaker above burning, and for seven hours it blazed, cutting off both egress and oxygen, till the whole mass collapsed. Burning timbers fell into a choking, smoking heap, a pile forty feet high at the bottom of the shaft, burning to charcoal as the rescue teams helplessly watched. One hundred ten men and boys died that day; the youngest eight years old; many with faces to the floor as if they could somehow extract one last breath of sweet air from the very coal dust.

After that the reforms began; there had to be two exits, and the breakers had to be away from them. After Avondale, boys under fourteen could no longer work in the mine itself, and twelve was the minimum age for the breaker.

So, on a cold and gloomy late winter morning in 1879, Jack Murphy, twelve goin’ on ten, walks to work; and so to one side of the breaker, from the mine itself, men with blackened face and garments issue, the bright, flickering little tin lamps on their hats the sole counterpoint to the grime.

They are the night shift on the way home; the day shift already down below in such relief as is to be had. They walk stolidly, carelessly swinging now empty lunch-pails; the marks upon them of their forbidding calling fascinate young eyes ‘til these warriors of grim and deadly battle waged in sunless depth pass from view.

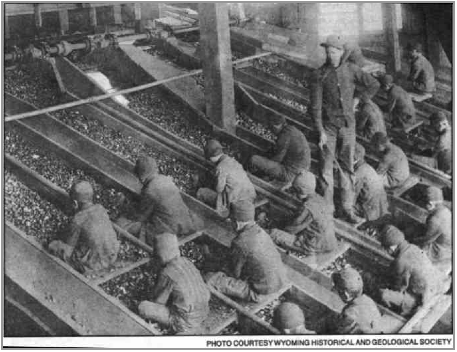

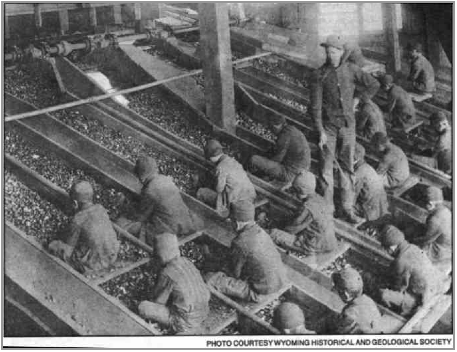

Little Jack climbs the long, steep, cleated ramp paralleling the coal chutes with their tough endless iron troughs, laden with the broken offerings of the far below miners, the fruits of their dark toil passing endlessly by; as boys crouch on wooden slat seats, straddling the flow, using their legs to push the conveyors of coal pieces, bending for hours at a time, wearing callused fingers and torn nails against iron, grabbing deftly at bits of slate mixed with the coal, tossing them aside into the tailing chutes. He finds his place and sits. There are five or six boys, one above another, over each trough. The coal is expected to be pure after it flows on past the final boy. It is as a form of religious duty; all pay homage to the coal.

Breaker boys carry an air of supreme independence. They swear long oaths with skill and seem proud of their villainy. These urchins are a terrifically dirty band. They inhale the dust until lungs grow heavy and sick. The clamor rings in ears until it is wondrous they can hear at all.

Despite his youth, Jack proves good with his hands, and not only in work. He is tough, uncompromising. He is not afraid of the other boys, even the big ones. He is uncowed; he swaggers. He gains more prestige than the average nine or ten year old, moves to a more preferred spot over the chute, one nearer the bottom where the coal is cleaner and there’s less to do. Jack very much aims to be the alpha male of his little band; he is ever challenging, seeking advantage, using his wiles to advance himself.

Down in the midst of hell he sits, working hard for his fifty-five cents each day.

During breaks he plays baseball, out on the culm heap, or fights with boys from other breakers or among his companions, as opportunity presents, while overhead arches a sky of soft pastel blue, incredibly distant from his sooty life.

When Jack laughs – and often he does, this cocky boy – his face is a wonder and a terror, white eyes and gap-toothed grin startling contrasts in face of lamp black night; through ragged shirt glimpses of shoulders, black as the coal they serve.

And yet at end of day, coal black night comes, and Little Jack runs home as fast as his young legs can carry him, panting in terror, sure that he will find his father and all his brothers dead, and himself alone. Nine is a tender age no matter how tough the exterior. Abandonment is a fear for every child, even the toughest of boys. Naturally, he does not speak of these things.

Time moves on, and Jack moves with it, up in the world; or more literally, down.

Every breaker boy hopes one day to be door-boy in the mine; and, later, mule-boy; and later yet, laborer and helper to the miner, each step bearing a higher wage and exacting a yet higher price in return.

Finally, when a boy is grown, if he grows to be a great and powerful man, then he may become a real miner.

Perhaps he will one day be Big Jack Murphy, and maybe he will have his day in the mines, for though Little Jack Murphy’s eyes are black like the coal, they burn as glowing hot and ambitious as ever did any anthracite.

Then he can have a wife and children and live the life of a man. Father Jack would be perhaps, if he were lucky, to a fine boy such as himself, and he’d name him Jack Junior. Perhaps.

And if he is so lucky as all that…why then, his fate is to escape a shattered old man: burdened with "miner's asthma," fit only for work in the breaker, robbed in the end of even the dignity, the manhood, of being a miner.

Coal mining becomes a business of generations, even within a single one.

A miner’s life starts as a boy in the breaker – and ends, as an old man, in the breaker. Once a man, twice a boy they say. Jack’s life may be no different.

Unless of course he gets squeezed.

* * * *

Mary Anne Ryan was an educated woman. She came from Ireland to be governess to her nieces and nephews, a high school graduate and qualified by teaching in the convent school in the old country; a woman who spoke three languages, and if one was lowly Gaelic, another was haughty French.

A woman with prospects she was, until she was raped – by her uncle, a rich and successful businessman with connections, father to the children in her care. Such shameful doings were not to be spoken of, and a woman who could not look after her virtue was presumed complicit. Her aunt showed her the door, never wanting this young, pretty nineteen-year-old with her narrow waist and fine features and wide brown eyes and educated ways and airs in her home in the first place.

But there are no jobs for a fallen governess. An Irish credential would serve nowhere but the parochial school; no school would take even a married woman with children for a teacher, certainly not a single girl of proven bad virtue.

Mary Anne Ryan married Jack Murphy, Jr. on a midwinter afternoon in January, 1915, and became a coal miner’s wife; better than washerwoman or whore, her two other career options. Jack Junior, for all the roughness of an upbringing by a very tough father in a tough world, was mad in love with her and soft as butter in her hands.

Too bad she did not share his feelings. She didn’t think much of her choice. He was a man to give name to her illegitimate, incest-spawned son; and eventually to too many more children of his own.

It was a bitter marriage, a loveless aching life for a smart woman who had once had prospects. To Mary Ann, Jack Junior was a stinging choice from a set of equally poor choices, the local maxima on the bounded curve that was her life. The best available alternative, or so she often said.

Her first borne later that year she named for him, Jack, though both knew he was her son and her cousin and no relation to him at all.

Mary Anne hadn’t found sex particularly worthwhile, and despite another sin involved made sure she didn’t have a second child until she wanted one – for herself.

Daughter Evelyn, her second borne, would remember her daddy Jack Junior as a sweet man; he loved his little garden behind whatever ramshackle house they rented, tended to it with a religious fervor, and as well he was devout Catholic. He was, all in all, not so much like Jack Senior. He was submissive to his angry, sharp-tongued wife, and lacking in ambition as his choice for a wife demonstrated. Softhearted he was, seeking only the peaceful pleasures of a tender moment with his child. He would hold little Evelyn in his lap after church, sitting in the old wicker chair on the porch, softened on Sundays only, with her mother’s hand-embroidered needlepoint cushions, and sing to her in a fine Irish tenor.

That was what she remembered best, that was what kept her sane after, when life as a coal miner’s daughter unfolded upon her.

Evelyn’s grandfather, Big Jack Murphy, was long gone, in a small incident, squeezed until his eyes no longer burned with intensity, then squeezed until the light in them was extinguished as a poorly shored section collapsed, unremarkable amongst a half-dozen similar accidents in the valley that year. Big Jack was the sole fatality that time. Perhaps an earlier crew had been a little too frugal – in those days, like the lamps and wicks and kerosene on which life depended, shoring material was the mining crew’s obligation to supply, not the company’s. The coal belonged to the company, the space it occupied was the miners’.

She visited the curse of intelligence upon her children, raised them with culture, took them to the nickelodeon and real plays when possible, read to them, sent them to parochial schools, taught them herself. Perhaps it would have been better not to do so, perhaps a life of ignorance is preferable to one of knowing and never being able to reach, never to connect, never to achieve. What need a coal miner’s son or daughter for culture? Ignorance is bliss.

At least, that’s what they say.

* * * *

It was different after the unions had gained a measure of control and the laws strengthened; the boys really had to be twelve to start and the worst of the dust was damped and the hours of labor for the boys diminished to thirty in a week until they turned fourteen. Then they were old enough for the mine and a miner’s life.

Thus Evelyn’s father led a life fractionally less hard than his father; had a fifth instead of a third grade education, two-thirds more; spent a mere sixty hours instead of seventy-two in the mines each week, one sixth less.

And yet his life was not much different; still he came away with little money, his pay owed to the company store, most of it docked away before he saw it, and much that was left over went to drink, the only escape from this dark drudgery, this life in hell. This was the calculus of a coal miner’s life, for inside a man those hard lumps of anthracite would remain unbroken, inevitably exacting their internal toll, grinding him down.

Then the day came – they were becoming generational tradition in this family, these special dark days— five other men were with twenty-seven year old Jack Junior in the cold and wet and impenetrably dark bowels of the valley, squeezed to heaven expressed direct from hell with an incense of blasting powder smoke, coal dust, oil, and earth. If anyone cared – and no one really did, nor in the end did they know – it was one’s careless moment with a lamp compounding another’s with an open powder box, and merciful quick it was, for which all who remained later gave thanks to God.

There was no workmen’s compensation, no disability insurance, no life insurance, no survivor’s benefits; the mine would not even pay to bury him, though they did dig him up first – burial was the union’s job. He left a pregnant wife and five children, Evelyn’s brother the eldest at thirteen, Evelyn herself a mere ten.

Like a wildflower in a weed patch, Evelyn grew, surpassing her mother in beauty and intelligence and ambition, none of which was any damn advantage in this coal-sodden valley.

At a spinsterish twenty-six she married beneath her ambitions - little choice she had - another grandson of Ireland, another progeny of the coal fields, Thaddeus Holmes, a man of demeanor amazingly meek to even her father’s example, accepting his fate as passive mate to an unhappy wife.

Well, she was pretty, and she bore pretty children, five of them, until, as the night followed the day, it was his turn. The mines were safer, but safer is not safe. Not so quick, not so merciful; two limbs lost to machinery and death from shock and blood loss and infection a few days later.

Not exactly squeezed.

Fractionally better.

Or so they might say.

* * * *

At least once he was gone there was no reason to stay in this narrow valley, this Iron Maiden, this filthy place. Evelyn Murphy Holmes moved, north and west, to a city, a place of culture and industry and wealth, even if it was colder; and most of all a place without coal mines, coal dust, coal miners, or coal memories.

No more of hers would be left for squeezing in that hideous dark.

Wealth did not, of course, mean wealth for her. A widow with a tenth grade education, eight children, union widow’s pension and now social security – pittances they were, based on her husband’s meager wages – had neither money nor career paths to pursue, no matter how sharp her mind. Or tongue.

Even here Evelyn was a very frustrated woman, her intelligence and ambition smoldered in an airless world where her gender and lack of formal education ensured she would never find fulfillment.

There came a brief procession of men, better heeled than her dead husband, more educated, more able to appreciate her mind, yet none wished to be saddled with five, then six, seven, and finally eight children of other men.

In this new place Evelyn moved often, as each of her last three were born. In a big city any reputation can be buried in indifference with fair ease and short distance. For though she did what she needed to make ends meet, to try to quench her loneliness and bitter anger with the warmth of a man, she would contain her sins: she would neither commit the unspeakable murder of the unborn; nor compound and double sin with contraceptives.

And yet, life goes on and one beauty of calculus is how unexpectedly elegant, balanced forms can issue now and again from the most stark and static equations.

Evelyn Murphy Holmes’ last born, would have been a delight to any mother not so badly used, nor so worn by time and events and frustration; one not so inured to a hard life; to one less familiar with the taste and burn of a leather belt in her mother’s furious hand.

To one not so burdened with the crushing weight of her own sins and God’s retribution.

One might think a pretty boy, to a woman whose brother was her cousin, a boy with her very own wide brown, yet so innocent eyes, his grandfather’s sweet disposition and voice; a boy with a wicked sharp mind – well a boy like that should be a blessing, a comfort, a hope for the future; a better future for a child is what all parents want, is it not?

Isn’t that what they say?

To Evelyn he was one more mouth to feed on too little money, one more soul to be damned for her sins, for her mother’s sins, for her great-uncle’s sins, one more reminder, in his every success, of every stinging failure in her life.

* * * *

The mines flooded. Careless mapping led one mine to blow out the wall to the river; the other mines closed when a rising flood swamped the area, shifted the river itself as it cascaded into the open shafts. The jobs gone, the lives played out, the breakers abandoned, this tired land sank into an even greater poverty. People left. The churches and the parochial schools mostly closed, the convent her sister Mary belonged to transferred her to this city where Evelyn lived and sinned. Two brothers followed.

Her father’s sweet tenor was too far away. She could no longer hear its gentling lull.

When Barry was singled out and sent to special schools, when he was offered scholarships to Princeton and Harvard, when his genius at mathematics emerged and his world opened wide it was more than she could bear. And when he finally left, it was no happy day for her, rather a vile one: now deserted by her father, her husband, all her ungrateful children; left only with a widow’s pension and a small monthly check from her eldest son; abandoned like the breakers; like the very mines.

Crushed beneath life’s weight.

Squeezed.

Author’s notes:

While Big Jack Murphy and his descendants are all fictional, much of this story is true.

My great-grandfather, a twenty-seven year old Civil War Veteran, died 6 Sep 1869 in the Avondale Mine Disaster. He left behind a two year old daughter and pregnant wife, who gave birth to a boy just three months later; that boy was my grandfather.

If a photo of a

coal breaker accompanies this story, it is in the public domain.

Intended: Coal Breaker, by George F Gates

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Coal_breaker,_by_Gates,_G._F._(George_F.).png

Some portions of this story are extensively rewritten or adapted from the publications below; the minor original, unchanged portions of those materials used here are in the public domain:

Calculus n.; pl. Calculi. [From Latin, calculus: a small stone used in reckoning.] …

1a : a method of computation or calculation in a special notation (as of logic or symbolic logic)…

3a : a concretion usually of mineral salts around organic material found especially in hollow organs or ducts…

4: a system or arrangement of intricate or interrelated parts

Webster's Revised Unabridged Dictionary, ©

1996, 1998 MICRA, Inc. at

https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/calculus?show=0&t=1360157661 Last

accessed 2/6/2013

Fellicific Calculus (non-mathematical): a method of determining the rightness of an action by balancing the probable pleasures and pains that it would produce.

Webster's Revised Unabridged Dictionary at

https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/felicific%20calculus Last accessed 2/6/2013

Barycentric calculus, a method of treating geometry by defining a point as the center of gravity of certain other points to which co[e]fficients or weights are ascribed.

(The Free Dictionary at https://www.thefreedictionary.com/ Last accessed 2/6/2013

© 2002, 2003, 2004, 2013 by Philip Marks, aka Fisher Boy, boyfisher69@yahoo.com.