Their Finest Hour

4. Wind-down

Doug’s leg healed and he returned to duty. With practice, our home cooking grew markedly better. And that spate of bombing, thank goodness, despite the grief it had dealt us when it began, proved intermittent and feeble and lasted barely three months.

Early in March, however, we were visited by a different kind of horror for which Hitler was only marginally to blame. It happened just outside our boundary, but such was its scale that reinforcements were whistled up from boroughs round about. Soon after dark the siren went and throngs of people headed for Bethnal Green tube station on the deep-level Central Line. From the street to the concourse was a flight of steps, and on the lowest step a woman carrying a child slipped and fell. Gunfire opened up nearby, and the queue accelerated. By all accounts it was orderly, not a stampede, yet with its sheer momentum it simply could not stop. Starting from the bottom, everyone else fell too. Bodies piled up, one on the other, until the staircase was full. Doug and I helped remove them, women and men, babies and pensioners, crushed or asphyxiated, and it was as painful as any of our experiences. The final count of dead was 183. The bitter irony was that the alert was a false alarm, and that the gunfire had come from new artillery being tested in a nearby park.

* * *

“Charlie,” said Doug cautiously, “you’ll never forget your family. Of course you won’t. But it doesn’t hurt quite so much now, does it?”

“No. Mr Goldstein was right. It’s a lot easier, especially because I’ve got you. And life has to go on. What makes you ask?”

“That bomb in Ocean Street. If it had hit me in the head, under the brim of my tin hat, it could have been curtains for me. But it hit me in the leg instead. So I want to be reminded of how lucky I am to be here. With you. Yet I don’t want to remind you of how your family went.”

I thought I could see where he was heading. “You mean you’ve got that thing the doctor dug out of you?”

“Yes. He’d slipped it into the parcel of dressings he gave me. Do you mind if we keep it on the mantelpiece?”

“Not in the least. It’ll remind me too of how lucky I am, that it didn’t get you in the head.”

He produced it, a jagged chunk of metal, an inch and a half across, with an evil silver glint. We put it on the mantelpiece.

* * *

We turned seventeen and became Rover Scouts. But there was little Rover activity these days because so many in the age group had been called up or, like us, had full-time jobs. Nor were we in tune with the thinking behind the Rovers, which we saw as another of Baden-Powell’s misjudgements. The theme of the Cubs was based on the Jungle Book, which was fine for real youngsters like that. As a counterpart for the Rovers, however, who were ten years older, B-P had plumped for the Knights of the Round Table, and he had wrapped them up in a mystic aura of vigils and purification and errantry which had more than a whiff of Sir Galahad. That struck us as ballyhoo. But we tried to be positive, and we helped the new leaders of the Scout troop at its annual camp in Epping Forest.

* * *

The evening we came back from camp we were sitting with a mug of tea after our meagre meal.

“Doug,” I asked wistfully. “Do you remember coffee? Proper coffee, not chicory out of a bottle?”

“God, yes! And all the chocolate bars our pocket money would run to!”

“And omelettes.” I was in a masochistic mood.

“Oh don’t,” he groaned. “Please don’t. Not omelettes. Not when we get one egg a week. Omelettes are sacred.”

“Eggs.” My mind was back in the countryside we had just left. “Do you think the troop could keep chickens? Fence off a run on a bomb site, or a corner of the churchyard?”

“Wouldn’t they get snitched, like the veg from our garden?”

“Mmm. And what do they eat? I’m an ignorant townee. I know they peck for grit, but do they need to be fed?”

“I’m an ignorant townee too. We’d have to ask around … But know what I need, even more than an omelette? Right now.”

I could guess, because I did too. We had to be abstinent in camp. And this was a need that was easily filled. Right now.

We asked around, and for various reasons the chickens fell through, so to speak. They had never been more than a whimsical and nostalgic notion prompted by a war that had been going on for far too long.

* * *

From January to April 1944 there was another small blitz, worse than the one of the previous year but nothing like as intense or prolonged as the Big Blitz of three years before, although the bombs were markedly heavier now. It offered the familiar menu of ruin and fire and heart-rending tragedies. But one night Doug and Sol came back to D1 grinning from ear to ear. Doug left the explaining to Sol. Their incident had been a bomb behind a terrace of houses. No damage had resulted, apart from windows broken and a flimsy wooden privy flattened by the blast in one of the back yards.

“Just a pile of planks, it wuz,” he said, “but it wuz squealing somefing dreadful. So we pulled it apart, and inside wuz this girl. Right good looker too.” He licked his lips. “Blown off the seat wiv her knickers round her ankles. Wuzn’t really hurt, but took us half an hour to pick all the splinters outer her bum, and everywhere else. What’s called first aid, innit? Cor, what a giggle! Biggest laugh since grandma caught her tits in the mangle.”

Barely was that spasm of bombing over than the Allies invaded France. Fire engines were brought south from all over the country to cope with the expected reprisals. But fresh raids did not come, or not in the anticipated form.

For months there had been vague warnings from the Government of a new secret weapon up the Germans’ sleeve. They did nothing to prepare us for the reality. On 13 June, just before daybreak, there was a noise above Stepney like the buzz or chug of a motorbike without a silencer. The sound cut out, and fifteen seconds later a row of houses in Grove Road was flattened. This was the first flying bomb, or buzz bomb, or V-1, or doodlebug as it was most widely known. It looked like a small plane with a tube on top, and it was vicious. With a warhead of a ton, it caused huge destruction. Up to a hundred a day were launched at London, so that we lived under an almost perpetual air raid alert. You would scuttle to the shelter at night, but by day you came to ignore the alerts because they gave no idea whatever of when or where a bomb might land. Life had to go on. What you relied on now was your ears. Hear the motorbike noise, and you stopped in your tracks. Hear it cut out, and you dived for cover.

With the arrival of the doodlebugs, we did not revert to our practice of the earlier raids. Then, the incidents we had to deal with were innumerable but, on the whole, relatively small. Now they were many fewer but individually bigger, and they might come at any hour of day or night. Blanket destruction had given way to localised strikes. There were no more incendiaries, and fires resulted only from broken gas pipes. A number of ARP posts were therefore mothballed. Doug and I, promoted now to senior wardens, tended to operate even more closely together as a pair, roaming the borough on troubleshooting missions. And because German planes no longer flew over us, the blackout was eased and replaced by the so-called dimout, which allowed a light level equivalent to moonlight.

But whereas the Blitz had generated stoicism — the Blitz spirit, we called it already — this new devilry spawned terror. There was a third mass exodus from London, larger than the first, with a million and a half clearing out. What with the dead and these temporary evacuees and people upping anchor for good, the population of Stepney was down to a third of its pre-war level. One benefit was that it made the place easier to look after. But all told we had fifty doodlebugs in the borough, spread over nine months, and together they did nearly as much damage as all the thousands of bombs of the Blitz.

As if this were not enough, in September a further devilry appeared. The V-2s were rockets that dropped out of the sky at more than the speed of sound and allowed no advance warning at all. The noise of their travel arrived after they did. The first you knew was the crump of the explosion. Being heavier than doodlebugs, they were more destructive still. The only saving grace was that there were not so many: an average of three a day hit London, and we did not experience our first until the end of October.

We had a new bomb disposal officer in Stepney, an extrovert and debonair young sapper lieutenant named Fergus Murphy. We met him a number of times, and at greatest length over a doodlebug that failed to detonate. Because these things fell from no great height, it was lying on the surface, battered but otherwise intact. Not trusting it an inch, we evacuated nearby houses and put up cordons generously far away in case it took it into its head to go off. Fergus, when summoned hotfoot by the Control Centre, went into raptures at having so good a specimen to play with. He set to work defusing it in person and alone, his team at a cautious distance, us at an even more cautious one.

“I hope he knows what he’s doing,” said Doug. “He must know that if it misbehaves he’s had it. How can people do that sort of thing?”

“Well, it is his job. But sooner him than me.”

After a long and — to us — nail-biting time, Fergus declared it safe, and his gang winched it onto a lorry to cart away for expert examination.

“Charlie! Doug!” he cried, bounding over. “Thanks so much for that.”

“Sounds as if you think we laid it on specially for you.”

“Didn’t you? Wasn’t it your good deed for the day?” He was eying the badges on our boiler suits. “I was a Scout myself once, long ago, so I know what you’re expected to do. But I’m not now, so I’ve given up good deeds.” He put his head on one side. “There’s something I’ve been wondering, though, if you don’t mind my asking. Whenever I see you two, you’re always together. Am I right in thinking what I’m thinking?”

We had not met this outright curiosity before. But we liked him and we trusted him.

“Yes.”

“Well done. And good luck!”

So Fergus, as well as being a former colleague, was evidently also of our persuasion.

* * *

Thus the winter passed, uncomfortable but manageable. Doug was worried because he had not heard from Fred for months. I offered what crumb of comfort I could.

“The Germans are under pressure. I’d guess that niceties like POWs’ mail are low down their priority list.”

Indeed by the beginning of March 1945 the war was clearly winding down. Germany was being squeezed hard from either side. It was nearly a year since the last conventional bombs had fallen. Doodlebugs, now that the Allies had overrun the launching sites in France, were markedly fewer. So far Stepney had had very few V-2s. Part-time NFS members had been stood down and many ARP wardens laid off. The Controller asked us for advice on how to cut back further still, once we were sure nothing more was on its way. One day, while working on that assignment, we were together in the west of the borough. Evening was closing in when we heard the familiar motorbike buzz of a doodlebug.

“Damn it to hell,” said Doug. “Haven’t had one those blighters for a month. Hoped we were shot of them.”

The buzz cut out. It was much too far away for the blighter to hurt us, but it was probably landing in our patch. There came the flash followed by the crump — somewhere, we reckoned, near the Bishopsgate goods yard on the railway into Liverpool Street. We rode towards it hell for leather. Yes, it was the goods yard. Men were milling around. Someone who seemed to be a foreman showed us a crater which had destroyed the entrance to a siding, and alongside were the mangled remains of a locomotive.

“Driver and fireman weren’t on board,” he said. “Nobody hurt, far as I can see. Could’ve been a sight worse.”

But a train of a dozen vans was parked in the cut-off siding and, from the roof of the end one, smoke was rising. Strange. Doodlebugs did not usually cause fires.

“Probably coal blown out of the firebox when the loco was hit,” the foreman said, following our gaze. “I’ve sent for the fire engine, but can’t do nothing more. The bastard’s buggered the hydrant main. Anyway, it’s only a van. Don’t worry about it.”

We did worry. The smoke on top was growing into flames.

“What’s in it?”

“Dunno. May say on the label.”

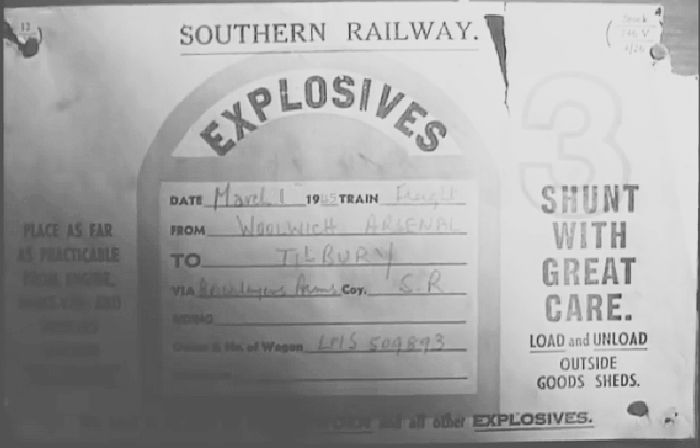

We went over and looked, and our hearts turned cold. All the labels on the vans were the same.

Explosives, en route from Woolwich Arsenal to Tilbury Docks.

“Hell!” said Doug. “If this one goes up, the rest will too.”

The foreman panicked and began to run.

“Come back!” I bellowed.

At least he stopped.

“We’ve got to separate that van from the rest. How do we get it moving?”

“Pinch-bar,” he said sullenly.

“Then bring one.”

I thought he would refuse, but he went. Meanwhile we detached the van, easily done because it was loose-coupled. The foreman came cautiously back, carrying a crowbar with a flat angled end.

“Get it moving!”

He put the bar between a wheel and the rail and levered. The van inched forward. The moment there was room we slipped in behind it, our shoulders against the buffers, and pushed for all we were worth. The van speeded up a little, but it was still at snail pace. The fire on top began to sizzle. There was a clang as the foreman dropped his bar and ran; for good, it seemed. But how far did we need to move this damned thing away from the rest? And even if the fire engine arrived in time, where was the water to come from?

The fire was positively crackling now. I did not want to die. Really I didn’t. Not even to join Mum and Dad and Brenda, because I had Doug. But it looked as if I was heading that way. Snippets of the past swam into my mind … ‘I don’t need to think, Dad. I’ll stay’ … ‘Well done, Charlie. That was very brave’ … ‘We stay together until the end, right?’ That memory was a comfort of a sort. If this was the end, we would be going together.

“Look!” panted Doug. A few yards ahead was a column where locomotives took on water. “Might be on a different main. I’ll try it.”

He ran to it, leaving me pushing alone.

“It is!”

He rejoined me. Aeons later, it seemed, we were in position. I rushed round and dropped the brake.

“Give me a leg up!” I was taller than him.

He gave me a mighty heave. My fingers caught on the edge of the roof. I hoisted myself up. The roof was covered in tarred felt, burning fiercely now. Heat was scorching my skin, singeing my eyebrows. Doug swung the column’s hose within my reach.

“Turn it on!”

He spun the control wheel and a torrent gushed out. Never have I been so glad to see water. I played it over the roof, which hissed and spat. The flames died away. Weak with relief, I continued to play. Mustn’t risk any sparks or embers surviving.

“It’s coming out under the door,” called Doug.

The roof must have burnt clean through. Yes, there was a hole. I pushed the hose into it. Fill the whole damned van up, just to make sure. Then at last, as I was clambering down, the fire engine arrived. We explained to the captain what had happened, and that everything seemed to be over. He was not comfortable.

“Tricky stuff, explosives. Better get a second opinion.”

This fire engine was a modern one with a radio, into which he spoke. Before long an army lorry rolled up. Out jumped an officer in khaki overalls. Fergus again.

“Might have guessed! Charlie and Doug, the terrible twins!”

He listened to our tale, looking at the dripping van and its label.

“We need to know what this explosive is. If it’s TNT, say, it’s safe enough and wouldn’t have gone up anyway. We’d better turn the water off and break in.”

Doug spun the control wheel backwards. The fireman took a crowbar and broke the padlock. The door, when opened, released a Niagara of water. Fergus shone a torch on the crates inside.

“Holy mother of God!” he cried. “It’s tetryl!”

“Jesus!” said the fire captain, reverently.

“What the hell’s the Arsenal up to,” Fergus ranted, “sending this stuff in flimsy little vans? God, I’m going to raise a stink about this.”

“Hang on,” Doug interrupted. “We’re just simple and ignorant ARP types. We know the effects of high explosives, and only too well. But we don’t know one sort from another. What’s tetryl?”

“A booster. For detonating a secondary explosive charge like TNT. Sensitive to heat. If it gets too hot, it goes off. If this van had gone up, it would’ve set the others off too. Maybe eight tons per van, say a hundred tons all told. Christ! There’d have been nothing left of you. Or of the yard. Or of most of the buildings within a half a mile. Did you know what you were doing?”

Doug and I looked at each other. “Well, we thought there might be quite a bang if we didn’t get the fire out. But we didn’t know it would be that big.”

“Any size of bang and you’d have been sky-high. Bloody heroes!”

“Heroes? Why heroes? It’s just the same as you defusing doodlebugs. It’s what we’re here for.”

“Whatever. But I need a drink after that, and so do you. Chances of another doodlebug right here are sweet FA, but we don’t want nefarious types tampering with this stuff. So let me just put a guard on it, and then we’ll buzz off to the pub and celebrate.”

We did not say no. We were careful not to drink while on duty, but we had found the occasional pint to be a good sedative after a stressful day. Even before we reached the legal age, a warden’s tin hat had always been an infallible passport to beer. And alcohol, like tobacco, had never been on the ration, even if supplies might sometimes be erratic. Fergus, having left a few men to watch over the tetryl, led us to a pub just inside the City. As we went he bought an Evening Standard.

“So they’re asking questions in Parliament about Dresden,” he observed, flipping through his paper as we sat with our pints. “What do you think about it?”

A couple of weeks before, the RAF had launched a monstrous air strike and left the city in ruins and no doubt many thousands of civilians dead. For the first time in the war, the public was beginning to question the military actions we were adopting to bring the Germans down. Editorials in some of the more serious papers pointed out that the war was already in the bag, that Dresden was not a strategic target, and that this smacked of outright terror bombing.

Our own feelings were mixed. We had been at the receiving end of precisely the same thing. Away from the docks, Stepney was even less of a strategic target. What Hitler had unleashed on us could only be described as terror bombing. We too had lost thousands of civilians dead. An eye for an eye, you might say — and plenty of people did: Hitler started it, let him have a taste of his own medicine. When monomaniac dictators — or, for that matter, power-hungry nations — get too big for their boots, they have to be restrained. Yet German civilians were as innocent as British ones, even though they were German. Two wrongs do not make a right. We said so.

“Yes,” Fergus replied. “It’s a tricky one, isn’t it? But there’s a difference between us — no offence intended at all. You’re civilians and you think civilian. I’m a soldier and I think military. As I understand it, Dresden was a strategic target. Lots of munitions factories. Huge marshalling yards — it’s a railway hub. It’s close to the Russian Front, and it’s surely legitimate to disrupt German supply lines. And as for the war being in the bag, well, maybe it is. But isn’t it our duty to do all we can to shorten it? The longer it goes on, the more people are going to be killed. Agreed, it’s sad if they’re civilians. But doesn’t saving Allied lives take precedence over saving German ones? If your tetryl had gone up today, tens of thousands of our own civilians would have copped it. If the war had ended yesterday, there wouldn’t have been any risk of it going up.”

We continued to argue, without result because no result was possible. It was one of those inevitably murky upshots of the insanity of war, and no doubt people will still be arguing the matter in fifty years’ time.

None the less the beer had done us good. We went home, and to bed, to recover further. Duty over, rest in peace. Boys long ago, but now grown up, still together until the end.

* * *

Stepney’s war, however, did after all go out with a bang. So far we had suffered only three V-2s. In the second half of March alone we had four more, and the last of them was by far the worst. On the 27th, two large blocks of flats called Hughes Mansions in Vallance Road were almost totally demolished. So great was the mess that searching the site took a week. The final count of dead was 134, of whom 120 were Jewish, and it was particularly cruel because it happened to be the eve of Passover. Once again mass burials were the order of the day.

But just as Stepney had received London’s very first bomb back in 1940, this one proved to be not only London’s last V-2, but London’s very last bomb.

* * *

April saw various loose ends tied up. The evacuees, nearly all, came back. We heard, to our unbounded astonishment, that for our escapade in Bishopsgate goods yard we were to be given Bronze Crosses by the Scouts and George Medals by the King. Fergus, we strongly suspected, was behind it, but did we really deserve them? Then on the 23rd, St George’s Day, to universal relief, the street lights came on for the first time since 1939. The same morning found the pair of us back on St Dunstan’s church tower. No ack-ack guns today, no blimps, no dogfights in the sky, but on every side stark ruins and the arid wildernesses of bomb sites which would soon be carpeted purple-pink with willow herb. If we had had all too few open spaces before, we had plenty now.

“Most of what Hitler has left,” said Doug, gazing, “will have to be pulled down. The only option is to start again from scratch. It won’t be the Stepney we knew. In some ways it’ll be better. But the old community will be gone. We’ve lost a lot of it already. We’re going to be losing more.”

“To be selfish, though, we’ve gained a lot as well, us two.”

It was nearly five years on from that first defining milestone, and on the very same spot. Together then, and together still. But back in those days we had recognised only comradeship. Now we had a bond that was stronger by far. We looked at each other in solemn communion. We saw that, as usual, we were thinking the same. We ducked down behind the parapet, where we not only hugged but kissed.

We were on the tower because, as senior wardens, we had been given the task of liaising with Fergus, who was beginning to systematically clear the borough of an astonishing number of UXBs. Our work, for a change, was easy. Once we had located the sites from experience and from the wardens’ records, he and his gang did the dirty work of digging for the things and disposing of them. Some they defused and carted to the Kent marshes to blow up, some they destroyed on the spot with controlled explosions. This morning they were dealing with one in St Dunstan’s churchyard. For years it had languished behind barricades and warning signs, but being in nobody’s way it had stayed low on the priority list. It was some distance from the church itself, whose windows had long since been boarded up, and there should be no damage; but out of courtesy we had notified the rector.

“This one’s an old friend,” Doug had told Fergus when we met up that morning. “It nearly did for me. Quite early on, it was. October ’40. We were messengers then, and I was cutting across the churchyard when it whistled down. A small one, I’d say — you’ll probably find it’s a fifty-pounder. It thumped into the ground ten feet away and spattered me with dirt. You know how it is. When disaster threatens, you freeze. Then in the last act of survival, you run. Well, I froze, then I ran. Even running, of course, wouldn’t have done a blind bit of good if it had gone off. But it didn’t. I thought the bugger might be delayed-action, but it wasn’t. Must be a dud.”

“How old were you?” Fergus asked.

“Fourteen.”

“Christ.”

So while they excavated Doug’s friend, we had climbed the tower for old time’s sake and from there we were watching them dig. When Fergus called us we went down, made doubly sure nobody was in range of flying bits, and retreated with the gang. The bomb expired with a muffled woomph and a spray of dirt, and the men began to fill in the hole.

“One down,” said Fergus happily. “A hundred and twenty-seven to go.” He looked at his watch. “Time to break for lunch. We’ve got sandwiches. Have you?”

“No,” said Doug. “We’re going to the British Restaurant round the corner. We half-starved yesterday, saving up goodies for tonight.”

“What’s happening tonight?”

“My birthday party. Sorry, Fergus. Just the two of us. You know why.”

“Fair enough. Many happy returns then, Doug. And very appropriate, because I’ve got a little present for you.”

He handed over a dented chunk of metal.

“The nose plug from your late lamented friend. It came off nice and easily, and I thought you might like a souvenir of your near miss.”

“Oh, lovely! Thanks a lot, Fergus. Guess where this is going, Charlie!”

“Where?” Fergus asked.

“On our mantelpiece. Alongside a bit of bomb that got me in the leg two years ago.”

“If you were fourteen for your near miss,” said Fergus, doing sums in his head, “you’d have been sixteen then. And that makes you only nineteen today.” He looked at our senior wardens’ helmets, now white with black stripes. “Christ! You nineteen too, Charlie?”

“Still eighteen.”

“God! Babes and sucklings. Thought you were old men like me.” He must have been all of twenty-five.

We laughed. “We’ll be back in half an hour, Fergus. But we’ll have to clear off about four, remember, for that other thing.”

“Understood.” We had told him why. “I’ll have to change too. I’ve got a proper uniform in the wagon.”

So he was coming as well. We had not invited him, or anyone else. Our suspicions increased that he had been responsible.

On our return from the restaurant, another and major loose end was tied up. As we entered the churchyard, there ahead of us was a man in khaki battledress, making for the porch. Something about him seemed familiar. Doug stopped dead and clutched my arm. Then he ran forward yelling “Dad! Dad!”

A reunion such as this, I find, is difficult to describe without becoming over-sentimental. So I will not try, except to say that it was sentimental. Not only for father and son, but for me too. His Stalag, Fred told us, had been liberated the previous week. He had been flown home, processed by his regiment, and released with a massive backlog of pay, a massive backlog of overdue leave, and double ration coupons. He had gone first to the flat and, unable to get in, was returning to his old stamping ground in the parish room. The double ration coupons were because he was badly undernourished and emaciated. Without elaborating, he implied that conditions over the last few months had been grim. But, three years though it might be since we last had met, he was still the same Fred.

Then Fergus came in search of us and was introduced. “Welcome back, sir! And excellent timing!”

Fred was puzzled. “What do you mean?”

“Oh,” said Doug lightly, “there’s a do this evening at Roland House that we’re expected to attend.”

To divert further questions I changed the subject. In any case they needed private time together.

“Look, Doug, you take Fred back to the flat … uh, sorry, I mean Mr Bruford.”

“Fred let it be. After all, you’re my equal in rank now. I hadn’t heard about your white hats.”

Pleased, I carried on. “And I’ll stay with Fergus. Then I’ll try to find more meat for tonight, and more bottles. You see, we’re having a little celebration for Doug’s birthday. But we hadn’t bargained on you being here, so there’s only enough for two. Could I borrow your new ration book?”

I set Fergus going on the next UXB, which proved an easy one. And the one after that. Then I headed for the butcher and mercifully had to queue for no more than a quarter of an hour. Extra booze took no time. Back to the flat for a wash and brush up and a change into Rover uniform, including for good measure our ARP armbands — a bit of both worlds, again. Doug had found Fred’s old scoutmaster’s kit and persuaded him to put it on. Our ceremony was due to begin at five, and we presented ourselves at Roland House with no time to spare. Waiting in the hall was a small bevy of very senior Scouts.

“I remember a few of these,” said Fred quietly as we came in. “But who are they?” He nodded towards two of the oldest.

“The one on the left’s the District Commissioner. The one in the kilt must be the Chief Scout. Lord Rowallan. Haven’t seen him before. He’s only just taken over from Lord Somers, who died last year.”

“Top brass, eh? You still haven’t told me what this is all about.”

But we were being chivvied down to the chapel in the basement, a small room already full almost to bursting. The whole St Dunstan’s troop was there under Sol, its current leader. Fergus was there, in something much smarter than his usual dirty overalls. And so too, in his dark blue ARP battledress, was Mr Goldstein, whom Sol must have smuggled in. That was good, because recently we had seen him little.

Doug and I stood side by side at attention. Someone read the citation. There was an audible gasp as Fred finally realised what was going on. The Chief Scout said a few words of commendation and praise. Only one bit can I remember.

“This is what scouting is all about. Remember the Law. A Scout is loyal. A Scout’s duty is to be useful and to help others. That is what you two have done, at a personal risk far beyond the ordinary call of duty. You, and the likes of you, may never have fired a gun, never have sailed a ship, never have flown a plane. But you have done more for your country than many a serviceman.”

To each of our shirts he pinned a Bronze Cross, and he shook our hands. A further very private chat and, the formalities over, Doug beckoned Fred forward. The Chief Scout had probably been wondering who this scruffy individual was, with tears wet on his gaunt cheeks and a creased and moth-eaten uniform hanging loosely from his bony frame.

“May I introduce my father, sir,” said Doug. “Fred Bruford, scoutmaster of the 11th Stepney Troop. He’s just today come home from three years in a POW camp.”

“Good heavens!” exclaimed the Chief Scout, returning Fred’s salute and shaking his hand. “Well timed, sir! Very well timed. And welcome back to where you belong!”

Fred stammered a reply, apologising for his tears.

“No shame in tears, sir. It’s a day made for emotion. The war on its last legs. A reunion with your son, whose birthday I understand it is. Pride in his achievement and the achievements of your troop. And it will be a day for further emotion when the King invests these two with their George Medals.”

As Fred gasped again, he was commandeered by the warden of Roland House, who was an old friend; while I made a mental note that we really must invite Auntie to that investiture. She would never forgive us if she missed it.

The evening plodded on. A well-meaning event, but hardly up our street, and it embarrassed us. Extricating ourselves as soon as we decently could, we returned to the flat to change, cook, celebrate, and talk far into the night. One topic deserves recording.

“You want me to use your old room, Doug?”

Doug took the bull by the horns. “If you don’t mind, Dad. We moved into your room because of the double bed.”

“Does that mean what I think it means?”

We were on the sofa, and gripped each other’s hand. Were we imagining it, or was there a twinkle in Fred’s voice?

“Yes, Dad, it does. For two years now. Ever since we moved in here. The strange thing is we hadn’t recognised it long before.”

“Hadn’t you?” Fred chuckled. “You must have been the only ones. No, that’s a gross exaggeration. But your parents, Charlie, had put two and two together, and so had I. We were entirely happy with it. You seemed to be made for each other, and if that was the way your nature was taking you, we reckoned we had no right to interfere. But you had to work it out for yourselves, and I don’t find it at all strange that it took you a long time. Both of you were always so … what’s the word? Pure-minded? Simple-hearted? … No, virginal.”

Doug let out a deep breath. “Then you don’t think we’re unmanly, Dad? Like in the Tenth Law?”

“You two unmanly? You must be joking!”

* * *

Thus we entered the final lap, or almost the final lap because Japan still held out. To Londoners, however, Germany meant so much more. President Roosevelt, that stalwart ally, had already died. Now Mussolini died too, and so did Hitler, good riddance to both. Public anticipation mounted. Civil Defence was stood down, at which we felt a twinge of regret, although we were kept on the books to liaise with Fergus. On 7 May it was announced that the next two days would be public holidays, and the nation made itself ready. Flags and bunting — taken off the ration specially for the occasion — were strung up along the battered streets.

At last, at long last, came Victory in Europe Day. It was also my nineteenth birthday. We were up with the lark. The sun shone. Church bells rang. Ships hooted on the river. Everyone laughed, everyone danced, everyone sang. Later there would be street parties, and bonfires, and public buildings floodlit. And, far from the least, there was the crowning moment to savour.

“Hostilities will end officially at one minute after midnight to-night, but in the interests of saving lives the ‘Cease fire’ began yesterday to be sounded all along the front, and our dear Channel Islands are also to be freed to-day. The German war is therefore at an end.”

The three of us — three, not two, now that Fred was back — were listening to the Prime Minister’s broadcast. The place was our sitting room. The date was 8 May 1945. The time was three in the afternoon. The news, though hardly news by now, was an undiluted relief. Churchill had more to add about crushing Japan, the final foe; and more about the indispensable parts played by the Commonwealth and Russia and the United States, and quite right too.

The wireless reported that in the evening he would be making a public appearance at the Ministry of Health. On the spur of the moment we decided to go; just the two of us, Fred having already arranged to celebrate with his old pals in the pub. The District Line train to Westminster was packed. Parliament Square was packed. We squirmed round the corner into Whitehall, which was also packed. And there was the Ministry. There were its flag-draped balconies. There, before long, were the senior members of the Government, Winston Churchill in the centre. The crowd went wild. He spoke off the cuff, with a message more personal to us than his broadcast had been.

“My dear friends, this is your hour (No, cried the crowd, it’s yours!). This is not victory of a party or of any class. It is a victory of the great British nation as a whole. We were the first, in this ancient island, to draw the sword against tyranny. After a while we were left all alone against the most tremendous military power that has been seen. We were all alone for a whole year.

“There we stood, alone. Did anyone want to give in? Were we down-hearted? The lights went out and the bombs came down. But every man, woman and child in the country had no thought of quitting the struggle. London can take it. So we came back after long months from the jaws of death, out of the mouth of hell, while all the world wondered.”

Anonymous in the depths of the cheering crowd, Doug and I stood silent, hand hidden in hand, emotions overloaded, tears streaming. Tears of joy in each other. Tears of pain that Mum and Dad had not seen this day. Tears of relief that, out of the mouth of hell, Britain had made it, that London had made it, that the two of us had made it. We hoped we had done our bit. Beyond argument the Boy Scouts had been useful and had helped others, as their Law decreed. More than that: they had so borne themselves, to borrow Churchill’s words, that in years to come men would still surely say, ‘This was their finest hour’.

But the war had been long. The journey had been hard. And we were very weary.