Chapter 7. On the Way

The king of the city of Sagala was named Milinda. He was learned, eloquent, wise and able, and a faithful observer of all the acts of devotion and ceremony concerning things past, present and future. Many were the arts and sciences he knew … As a disputant he was hard to equal, harder still to overcome, and the acknowledged superior of all the founders of the various schools of thought. And as in wisdom, so in strength of body, swiftness and valour there was none in all India found equal to Milinda. He was rich too, mighty in wealth and prosperity, and the number of his armed hosts knew no end.

The Buddhist view of Menander, from the Milinda Panha

Was this disaster?

“No,” said Zeno the perennial optimist, as Menkhes steered away from the land again. “It’s a relief, in a way. We’ll overtake it. Provided it’s not too far in front.”

Hours later his confidence proved justified. A sail became visible ahead, a big sail, growing slowly bigger. The little Tyche was faster than the lumpen Ammon, and gradually we caught up. As we drew near, I stood in the bow yelling “Hippalus!” until the captain appeared on deck, followed by Eudoxus. They looked, identified us, and waved acknowledgment. Menkhes slackened his sail and we drew abreast, on the side away from the shore. Throwing our baggage on board, we clambered across, and with a shouted farewell the Tyche veered off and crept ahead. Nobody on land could possibly have seen the transfer.

Eudoxus was almost as relieved as we were. He had not been looking forward to telling Menander that he had stranded us in Egypt, and he had had his own troubles at Myos Hormos, where the police had put him through an inquisition. He could not deny that he was expecting us, and they had searched the Ammon from stem to stern. On finding nothing, they had set a close watch, but of course in vain. We wondered how they would account for our loss. Possibly, when our abandoned belongings were found in the precinct of Ptah, they would assume that we had tried to escape by swimming the Nile and drowned in the process.

After the nail-biting traumas of our escape it was good to be back in the relatively luxurious safety of the Ammon’s deckhouse, where we could eat in comfort, wash off the lingering remains of the soot and, borrowing a razor from Eudoxus, shave. All Greeks prefer a smooth face, unless they are philosophers, and I have never been tempted to sport a permanent beard. Heliodorus shaved his boyish stubble. So surely would Zeno when the time came. Ram had always followed my example. Although Indians traditionally grow beards or at least moustaches, this was one of the few customs in which Gandhara was coming to imitate Greece rather than the other way round. That was doubtless why Menander was clean-shaven.

Thus, scrubbed and shorn and comfortable again, and heartily glad to be out of reach of the arm of Egyptian law and the miasma of interference and oppression, we looked forward to relaxing on the penultimate leg of our journey. Zeno, after exploring the ship, confided that he had found a space among the bales in the hold. Because Eudoxus and Hippalus might not approve of what he had in mind, would we keep a look-out while he and Heliodorus made up there for lost time? When after an hour they emerged, Ram and I went down while the boys stood guard. It was a deeply welcome discovery, and several times more we took advantage of it.

But alas for fond hopes of further relaxation. The route was the same as on the way out but in reverse. Once we had finished bowling steadily if ponderously down the Gulf, the south-westerly Etesian wind, when we picked it up near Adane, proved far more violent than the north-easterly which had wafted us the other way. As the Ammon, uttering dismal creakings, heaved stomach-churningly over the waves, we came to understand why only large and sturdy ships could make this passage. All four of us were flattened with seasickness, and to make matters worse Ram went down with a recurrence of his fever. The two do not go well together. All I could do, amid my own misery, was once again to hold his hand and try to cool his face; and, shamefully, not one of us remembered to congratulate him when his birthday fell due. Worse still, the wind blew us off course, so that we met the Indian coast too far south and had to spend three more days beating up to Barygaza.

There we tottered ashore and carried Ram to the governor’s house to sweat off the rest of his fever, and for all of us to recover our equilibrium. Only then could we ride north to Sagala and home. By the time we arrived it was the middle of October. It had been a mish-mash of a year, an amalgam of high discovery and debilitating tedium and agonising suspense. But the mental cost was heavily outweighed by the rewards. If Ram and I were elated by what we had found, Heliodorus’ face, as he led Zeno by the hand into our house to meet the family, was a picture of proud delight.

The welcome we received was rapturous and, on the part of the womenfolk, tearful. Ashmi had been convinced that she would never see us again, and repeatedly said so. Lavani, while she did not say so, had evidently thought the same. Bappa was as down-to-earth and paternal as only he could be. For poor Zeno it cannot have been easy. With everyone talking nineteen to the dozen and Heliodorus trying desperately to keep up with a translation, he was looking increasingly bewildered. Then the slap-up meal which was finally set before us left his face red and his eyes streaming, at which I had to suggest that next time it might be better if slightly less ginger and pepper were included in the sauce. We travellers retired to bed as early as we decently could, and the boys were quite indecently late in getting up.

Our next duty was to report to Menander. We took Zeno with us. The king was delighted to hear of our technical discoveries and everything that they meant for Gandhara; and he was deeply interested in all our other doings. He quizzed Zeno, necessarily in Greek, at such length that the afternoon session had to be extended to include dinner. Zeno, as quickly won over as Ram had been by Menander’s informality, unburdened himself about Egypt, occasionally inserting a “sir” when he remembered that he was addressing a king. He held forth about the iniquities of the police and the downtrodden lot of the slaves; about the burden on the poor of excessive taxation; about the atmosphere of suspicion and fear; about the flummery of Physcon’s court — here he looked meaningly around Menander’s simple dining room — compared to the restraint of this. From all that he had seen of Gandhara so far, he added, it revealed a sensitivity and tolerance and inclusiveness that he doubted Egypt would ever enjoy.

“Well, thank you,” Menander replied. “What you say about Egypt makes it sound rather like the Sunga realm, and even more like Bactria. You can pride yourself, Dion, that it was your forebears who laid the foundations that make Gandhara so different.”

“What do you mean, sir?” Zeno enquired. “What did their forebears do?”

Neither I nor, it seemed, Heliodorus had mentioned our ancestry to him. Until now it had never been remotely relevant to anything we had talked about.

“So they haven’t told you?” asked Menander. “No surprise, I suppose. They’re modest men, Dion and Heliodorus, who’d no more boast of their royal descent than the Buddha did. The point is that this kingdom — complete with its inclusiveness — was created in the first place by Dion’s grandfather King Demetrius, and moulded further by his father King Pantaleon.”

My son and I blushed, as if we had also been responsible.

Zeno was once again amazed. “Dion and Heliodorus descendants of kings!” he exclaimed. “And yet they’re still alive and kicking! In Egypt they’d have been bumped off long since. Every king there is liable to see other royal descendants as a threat that can’t be tolerated.”

Menander smiled at us. “Not here,” he said.

“At home,” Zeno told us as we finally left, “a chat like that would be totally unthinkable. There, they’re self-centred and power-crazed, Physcon and all the rest. They’ve got no modesty and no moderation. Their minds are closed. I was right, this is a place where things are done properly.”

Heliodorus showed him around Sagala and even took him to Srinagari to witness snow, which impressed him almost as much. But Zeno had less than a month in the north before he would have to set off for Barygaza to rejoin the Ammon. To nobody’s surpise, he rebelled, and Heliodorus was outspoken in his support. So I told him what his father had said about staying on, and with huge relief he sent, by way of Eudoxus, a letter postponing his return. Nor, again to nobody’s surprise, did he ever did go back to Egypt. He set about learning Gandhari, and next year he sent another letter begging for a further extension; and so on, despite querulous pleas from his father, until he came of age. If he went back, he pointed out, he would be tempted to say or do something dangerously unwise about the state of Egypt; and in any case he would not leave Heliodorus.

Menander, seeing where his heart lay in both departments, gave the pair of them official posts working with his son Antialcidas on improving the lot of the lowest rank. Over the next few years they did a good job at breaking down such barriers as still hindered movement up the social scale; or rather, it seemed to me, the boys did a good job, because Antialcidas, unlike his father, had a limited appetite for reform and an even more limited imagination. Thus they became, like us, servants of the realm. Once it was clear that Zeno was in India for good and for all practical purposes a permanent member of the family, we had a sculptor portray him, and very well he did it. Our mistake was to have it done not in stone but in stucco, and after the frosts of its first winter outdoors at Srinagari it emerged sadly flaked.

In our absence, we heard, everything had been quiet in Gandhara. There had been no trouble with our neighbours. The rains and the harvest had been good. But the main subject of gossip — no doubt much embroidered as it passed from mouth to mouth — was a recent series of ethical and intellectual debates between Menander and the renowned bikkhu Nagasena, from which the king had emerged with great credit. He had long had a high reputation among his people as a man of compassion and enterprise, and now a new reputation as a thinker was firmly established.

One loose end of the story of our visit to Egypt remains to be tied up. On his next voyage, a year after our return, Eudoxus came to Menander with the news that he had again been questioned by the police and — good man — had denied that he had brought us back. None the less he handed over a letter from the chief of police there who, it said, had some reason to believe that three Indians, by name Heliodorus, Dion and (mis-spelt) Pham, having committed a serious crime in Egypt, may have escaped to their own country and without, to make matters worse, an exit permit. In the interests of justice, would the king make enquiries and, if he succeeded in searching the miscreants out, send them back for trial and punishment?

Menander, who might have sent an immediate reply, delayed it until the following year, “in order,” he told us, “to let the trail grow a little colder.” When finally he did write, he said that to the best of his knowledge and despite the most diligent enquiries, his kingdom was harbouring no criminals of those names. He was sorry, but he could not help.

“From that far away,” he pointed out, “there’s nothing they can do. They can hardly send an army here, or even agents, to track you down and kidnap you. Don’t worry, they’ll simply forget about it all.”

And so they must have done. We heard no more.

*

The rest of my tale may be even more quickly told.

Our own life became fuller than ever. The two of us — no longer the three — spent much time demonstrating to Gul and Kavi the lessons we had learned, and we began to apply them. All of us had, in effect, to start again from scratch with our programme of spreading the message. Gul concentrated on improving irrigation channels by lining them to reduce loss of water. In a lengthy channel which passes through an area that does not need watering, it is a waste if half the flow soaks into the soil before arriving where it is needed. He therefore experimented with waterproof linings, whether of stone or gypsum mortar or bitumen or a combination of them. The upshot was a more effective use of what water was available.

With the machines, Ram and his brother Kavi found that, in some respects, they are easier to build in India, where there is plenty of large timber, than in Egypt where there is nothing but acacia trees which yield only small pieces of wood. The baiga was gradually replaced by the chain lift for raising water from such rivers as the Indus and Ganges and even at the shallower of the desert wells. The bucket wheel for moderate lifts, whether turned by flowing water or by oxen, found some use. But, being much smitten by the principle of rotary water power, they also applied it to rice hulling by attaching projecting trips to the axle of a water-wheel, which activated pounders not unlike the cam’maca but working at a very much faster rate and thus at a much greater efficiency.

They were smitten too by the principle of the cogged wheel, which they applied to crushing and pressing sugar cane in a single operation. They set two rollers close together, vertical if powered by ox, horizontal if by water. One roller was turned by the ox or water-wheel, the other by teeth meshing in the same plane rather than at right angles. When cane was fed between the rotating rollers, the hard fibrous stalk was cracked and the juice was squeezed out, with remarkable ease and efficiency, to be caught in a trough underneath. They even began to think of using water power to turn millstones for grinding grain.

The four of us were therefore busier, if possible, than we had been before. And it all worked. The machines released the labour needed to extend the land under cultivation, and with improved irrigation the land under cultivation was more productive. Gandhara, it is not immodest to say, had never had it so good. Strangely enough, after a time, this began to raise anxieties. More and more village headmen told us that, with the increased prosperity, unusually large numbers of babies were being born. The population had formerly been smaller than the land could support; if it grew too much, might it now outstrip the new productivity of the soil?

“Yes, I suppose it is a risk,” said Menander when we raised the matter, “but only a small one. Our very existence, over much of Gandhara, depends on the rains, and from time to time, the world being what it is, the rains are bound to fail. There’s nothing we can do about that, beyond what you’ve already done to minimise the effects. For the last twenty years we’ve been lucky, but one day they will fail again and there will be another famine. Many, sadly, will die. But that, for a while, will solve the problem of over-population, if problem it is. Perhaps it’s nature’s way of keeping a balance. Meanwhile, our duty is surely to keep the people as well-fed, and their life as easy, as we can.”

Whether he was right or not, we will not know for many years to come.

At the same time, but wholly unconnected with our work, our isolation was somewhat reduced. Word had spread among Egyptian merchants of the success of Eudoxus’ ventures, and further ships began to ply across the Erythraean Sea until there were five regular sailings a year and the promise of others to come. India was in closer touch with the west than it had been for a century.

More interestingly still, several years later, a window also began to open to the east. It started with the delivery to Menander of a letter, ornate but incomprehensible and written on silk. It had been entrusted in Chaurana to the master of a caravan who brought it on across the Imaus. All he knew was that it originated from the fabled Seres and was written in Tocharian, which presumably they hoped we could understand. Our only contact with the Tocharoi being the occasional caravan, there were few in Gandhara who spoke their tongue. But the master did, and the letter, when he translated it, turned out to be from none other than the emperor of the Seres himself. Report had reached him, it said, of the just and prosperous kingdom of Gandhara, and he asked for safe passage for a group of his emissaries, who were already on their way with the purpose of finding out more about us and in the hope of fostering trade in silk and jade. Menander replied with a letter, if less ornate, of warm welcome, and a year later there arrived five small men, as battered as I had been by their passage of the mountains, whose flat faces were not unlike those of the hillmen of deepest Kaspiria.

We knew far less of the Seres than we had known of our cousins in the west; in hard fact we

knew nothing whatever except that they produced the silk which reached us through an uncounted

succession of caravans and middlemen. And this encounter, as far as anyone was aware, marked

the first time that Greeks had come face to face with Seres. Not even Sikandar himself had done

that. With them, these five men brought a Tocharian interpreter. Although he had some knowledge

of the Seres’ language, he knew not a word of Gandhari, and once our few Tocharian

speakers had departed again with their caravans we were unable to talk to our guests. The

interpreter was, however, better than nothing because he did have some Bactrian. As a Bactrian

speaker, if by now a woefully rusty one, I was given the tricky task of teaching them, through

him, enough of our language to communicate directly. Once that was achieved, I returned to Ram

and to agriculture, and Heliodorus and Zeno took them over. They showed them much, including

many of Ram’s machines, and reported that the Seres were especially interested in the

water-powered rice pounder.

Sadly, however, it all came to nothing. The Seres succumbed to some disease, three died, and

their mission withered. The two survivors headed for home, but whether they reached it we never

heard.

Indeed they had arrived at an unpropitious moment. Time had flown by. Menander had now been on the throne for thirty years. He was growing old, his hair white, his tall frame stooped, and his final months were not happy. Civil war was stirred up in the Paropamisadai by two pretenders, Zoilus and Lysias, with the support of Heliocles in Bactria, and the last time we saw the king he was in unusually pessimistic mood.

“The lion is the king of beasts,” he said, “and when it is put in a cage, even a golden cage, it still faces out. That is how I live too: still master in my house, still facing out. But were I to go forth into the world I would not live long, so many are my enemies. Death holds no fear for me, but I would rather not die before I have to.”

“The same surely goes for all of us, sir,” I replied. “But do you remember our very first conversation, when we talked about that inscription in Alexandria? In middle age, fairness; in old age, good advice; in death, no regret. You’ve lived up to the first two in full. And when the time does come, as it must to everyone … in death, I hope, no regret?”

He laughed. “I do remember, Dion. No, no regret at all; except for the ending, because my work is unfinished. It’s at risk of being undone. Not your work, mind you — that will endure, and one of my greatest prides is that you’ve done it in my reign. No, my disappointment is that the frontiers are still not secure.”

Not long after this he returned to the campaign, where he died not in battle but in camp,

not bravely of wounds but humiliatingly of cholera. A light had gone from us. Bactria gloated.

All Gandhara, and much of the rest of India, went into mourning. He was revered as a saint. His

body was carried back to Sagala for cremation and his ashes were not placed in the royal

mausoleum but distributed, as the Buddha’s had been long ago, between the chief cities of

his kingdom where they were enshrined in stupas. Antialcidas reigned in his place.

Sadly, the son had inherited none of the father’s charisma or skills. The mess in the west was cleared up largely by chance. Bactria, it turned out, had laughed too soon. Within a few months another horde of nomad Sakai, pouring in from the north, put an end to Greek rule there. Gloriously or ingloriously, it had lasted two centuries since Sikandar first added the province to his empire. Heliocles went down with his kingdom, and the pretenders Zoilus and Lysias went down with him. But in the east Vasumitra, the current but short-lived Sunga king who had never lifted a finger against Menander, took advantage of the weakness of his much less popular son by attacking and soundly defeating him. One factor that lured the Sungas onto the warpath, ironically, was that agricultural productivity in the valley of the Ganges had by our efforts been greatly improved, and they were determined to have it back. We were forced to retreat ignominiously to the River Hyphasis, the frontier of nearly thirty years before, and the capital moved once again to Taxila.

Discontent with Antialcidas mounted. We heard mutterings in certain circles that he should be deposed and replaced by Dion son of Pantaleon, who had as good a claim to the throne. But I was not in the least tempted. My great-grandfather Euthydemus, I was sure, would have disapproved of my stance. My grandfather Demetrius would perhaps have been puzzled. But my father, I thought, would have understood. Quite apart from my lack of ambition, to confront the ruling king would mean civil war, which was the last thing that Gandhara needed. So I made it known as forcefully as I could that I was not interested. To his credit, Antialcidas, who must have been aware of the rumblings, believed me. Whereas the Ptolemies would have eliminated a potential rival and his offspring without compunction, he made it known in turn that he trusted me. This was no doubt because he trusted Heliodorus, at whose side he had long worked.

Ram and I, in the circumstances, were nowhere near as close to our new king as we had been to his father. But my son still was. Antialcidas now appointed him ambassador to Vasumitra’s successor at the Sunga sub-capital of Vidisa, charged with the task of trying to repair the battered relationship between the two realms. The Sungas being Brahmin, it was in Brahmin guise that Heliodorus went. With him he took Zeno under the title of his deputy, both of them now sporting beards in best Brahmin style.

“Diplomacy,” he told us unashamedly, “is largely a matter of pretence.”

Half a year later we happened to be on a tour of irrigation works near the Indus mouth, and continued east to visit them. It was the first time that Ram and I had set foot in Sunga lands. At Vidisa, with some pride, my son showed us a tall pillar topped by a sculpture of the Garuda-eagle, the mount upon which the great god Vishnu was said to ride. The dedication was not in our usual Kharosthi script but in unfamiliar Brahmi, and Heliodorus had to read it to us: ‘Erected to the God of Gods by his devotee Heliodorus, son of Dion from Taxila, sent by the great Yona King Antialcidas as ambassador to King Kasiputra Bhagabhadra.’ It was curious to see my name immortalised in stone.

From Vidisa, moreover, although they could not come with us, they sent us on an excursion to Bardaotis, a town along the road to Pataliputra. There, Heliodorus said, we would find a great stupa adorned with countless elaborate sculptures.

“Look carefully,” he instructed, “and one will stand out from the rest. It won’t be obvious who it represents. This will tell you.” He gave us a folded scrap of parchment. “But don’t read it until you’ve seen the stone. You’ll be surprised.”

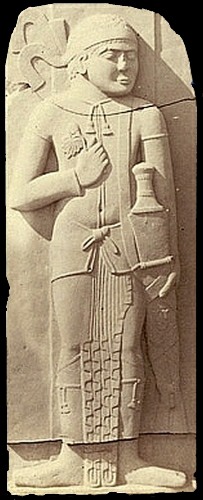

It took us little searching to find the sculpture in question. The stupa was surrounded by a massive circular railing of red stone, six cubits high and covered in carvings. Among the florid riot of symbols and figures of benefactors and scenes from the life of the Buddha — by themselves a wholly unexpected sight in these predominantly Brahmin lands, and evidence of the Sungas’ change of heart — what stood out in its simplicity was a relief of a soldier in Greek military garb. He was holding an ivy leaf, the mark of Dionysus the Greek god of wine. The scabbard of his huge sword was adorned with the triratna or trident symbol which represents the Enlightened — that is, the Buddha — and the teaching and the community. But the soldier’s face, being carved in formalised Indian style with none of the realism of Greek art, could not be readily recognised.

“Who is it, then?” I asked.

Ram opened Heliodorus’ note.

“It’s Menander!”

So … So … Even here, even in this land of different beliefs and different outlook which had never been part of Menander’s realm, he was remembered; not merely as a great warrior but, more crucially, as a statesman and sage and thinker who had embraced Indian ways. Ignoring the throngs of pilgrims who were milling around the stupa, we sat down in the shade of a nearby banyan tree to contemplate and revere his image, almost as he had contemplated and revered his image of the Buddha. If he was proud that our successes had been achieved during his reign, we were proud to have lived and worked under his aegis. Dare we call him our hero? Certainly he had been our very good friend, certainly our patron and inspiration. He had presided benignly over most of our life together. And that invited memories, both of his past and of our own.

Menander had been loved by everyone. Because of our mobile lifestyle, it was in the palace that our paths had most often crossed, and our meetings had usually been in private. But from time to time we had seen him in the streets of Sagala, where after a year or two he had given up his bodyguard and walked freely around with no escort at all except for a couple of servants to run errands. Although he wore no outward sign of his royalty, everybody, high and low, recognised him, and anyone was free to accost him. One more particular example of his common touch was engraved deep on my mind. To this day I can visualise him squatting outside a humble hut in some wretched village in the back of beyond and chattering with a gaggle of grandmotherly old women. Like them he was chewing paan, like them he was spitting without any selfconsciousness, like them he was scratching his fleas, or pretending to. And all of them were laughing their heads off as if he were their favourite son returned home after a long absence. A Greek by birth and upbringing, yet he was as Indian as any of his subjects. But were they really his subjects? Might one rather see him as one of them? Might one see them as his family? Might one even see them as his substitute for a lacklustre wife and son? What a very good thing that it was Menander who had become king, not me.

And then, alongside him, there was the pair of us, with thirty-five years of companionship behind us. Ram was now fifty. Flecks of grey were beginning to invade his hair, as they were mine too, but his ready grin had lost none of its cheeky charm. Nor had his body lost its lure. Nor, more important still, had his mind, which read mine more often and more accurately than ever. Now he took my hand in his.

“Here we are, Dion,” he said, “you and me. A half-Yona and an Indian. The son of a king and the son of a carpenter. Anyone can tell from the way we speak that we come from different walks of life. But that’s never mattered to us, has it? And it didn’t matter to Menander either.”

“No, it didn’t matter, not in one sense. But in another sense, wasn’t it something that he put great store by? That two people of such contrasting backgrounds should be in partnership, and that nobody should think twice about it? I doubt I told you at the time how disappointed he was when we parted company. But you were with me at the palace after the fire, and you’ll remember how delighted he was to see us back with each other. If we hadn’t made it up then, I shudder to think what I’d be doing now. Ram, why did you forgive me after I’d been such an idiot?”

“I’m not a dog or a snake,” he said almost sternly, “to bite when I’ve learned to love. When you arrived in Gandhara you were sick in the head, and I cared for you with all the love I could find. Whenever I’ve been sick with the fever, you’ve cared for me with all the love you could find. When we broke up you were sick in the head again, and while I couldn’t care for you then, I couldn’t abandon you either. Some things really are delusions, no argument. But the dove of attachment emphatically isn’t one of them. Doves, after all, mate for life.”

He crossed his hands on his lap and smiled, as a man may who has won salvation for himself and his beloved.

Salvation? We can hardly call ourselves followers of the Buddha. Sympathisers, yes, as was my father, but not followers as was Menander. As such, I hope we are not self-satisfied. It may be that we are simple-minded. Some might say that we have fallen into heresy. Yet it seems to me that Ram, by that act of supreme forgiveness in the face of my folly, set us on the path to freedom from the wheel.

We may not follow the Buddha, Ram and I, or not in every particular. But we do try to follow the Middle Way. We are guided, as we go, by example and experience. As an old Athenian put it in one of the few quotations that has stayed with me from my schooling, we love beauty without being extravagant, and we love knowledge without being soft. That described Menander, the most open-minded of men, and I hope it describes us. We are comfortable now with what we are and where we are. We intend to continue in that direction. It is not quite the direction we expected to take, or the direction we are necessarily expected to take, but it is the direction that is right for us. Even the Brahmins see it in rather similar light, that the quest for fulfilment is an individual one: any path we may choose becomes the right one.

We like to think that, with a single qualification, we have found the inner peace enjoined by the Blessed One. The three principal delusions to be avoided, he taught, are ignorance, hatred and attachment. Our stumbling block is attachment. It embraces greed which, like ignorance and hatred, is indisputably wrong. It also, so Dipankar claimed, embraces love; not just desire for the loved one’s mind, but for his body. I was admittedly not the best of students, for the cogs of my soul do not mesh with the gear wheel of such speculations; and perhaps Dipankar was not the best of teachers. But in so far as he bracketed love with greed, our thinking parts company with his. And therefore, if he was right in his interpretation of the Buddha’s message, our thinking parts company with that of the Enlightened One.

To live fully, it takes two. As Ram put it all those years ago, one leg is not enough to walk with. Back then, I had hardly understood. Now, in the maturity of our togetherness, I do. To us, love is the meeting, without shame and without reserve, of two people who have no barrier between them, and no pride. To us, long experience has shown that love is the most blessed of all bonds. To us, love is the ultimate and indispensable attachment. It stands inviolable. Not even the most rigorous practice — not even (dare I suggest?) perfect enlightenment — has the power to erase it.

So say I; and Ram agrees.

*

Over the next hundred-odd years, piece by gradual piece, the kingdom of Gandhara fell even further apart. Fragments splintered off, fresh waves of invaders swept in — Parthians from the west, yet more nomads from the north attracted by the new fertility of India — and around AD 10 Greek rule came to a final end. None the less, the Greek language was retained on coins until AD 151, and pockets of Greek speakers survived no doubt for centuries more. So too did Indo-Greek art, complete with its once-revolutionary images of the Buddha which rapidly became the norm. And so, of course, did Buddhism itself, which with Menander’s active encouragement had already begun to spread north to the Bactrians and the Tocharoi and before long stretched its long arm east into China. Greece — and one Greek king in particular — had left an indelible mark.

The whole earth is the tomb of famous men. Not only are they commemorated with monuments and epitaphs in their own country, but in foreign lands they have unwritten memorials, graven not on stone but in the hearts of men.

If you like the story, please help keep this site on the web by clicking on the PayPal Donate button at the top of the Home Page.