“And they likewise, bound upon the Wheel, go forth from life to life — from despair to despair,” said the lama below his breath, “hot, uneasy, snatching… Enter now upon the Middle Way, which is the path to Freedom. Hear the Most Excellent Law, and do not follow dreams.”

Rudyard Kipling, Kim

Introduction

Not everyone, perhaps, will be aware that for nearly two centuries the ancient Greeks ruled present-day Afghanistan, and for another two centuries ruled Pakistan and north-west India. But so they did. Sadly, we know much less about it than we would like. All their home-grown chronicles have perished. Western Greek, Indian and Chinese sources offer only meagre snippets of information. Coins of the Bactrian and Indo-Greek kings supply the broad but emphatically not the exact chronology. Archaeology is of limited help. Thus, although an overall pattern emerges, the detail remains highly uncertain, sometimes conflicting, and hotly debated. What follows is not only a story but, just as much, an attempt at a portrait of this little-known society. While I hope it is roughly accurate, it is inevitably much coloured — even perhaps a trifle rose-tinted — by my own interpretation and yet more by my own imagining.

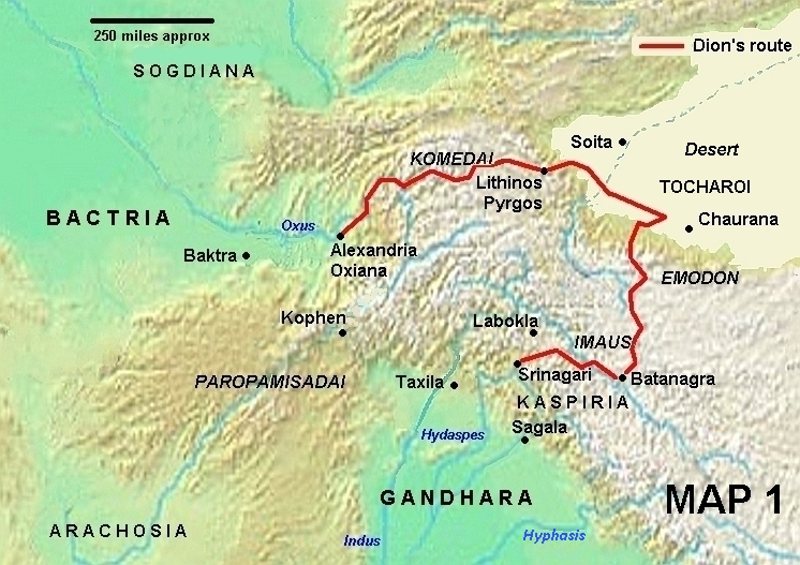

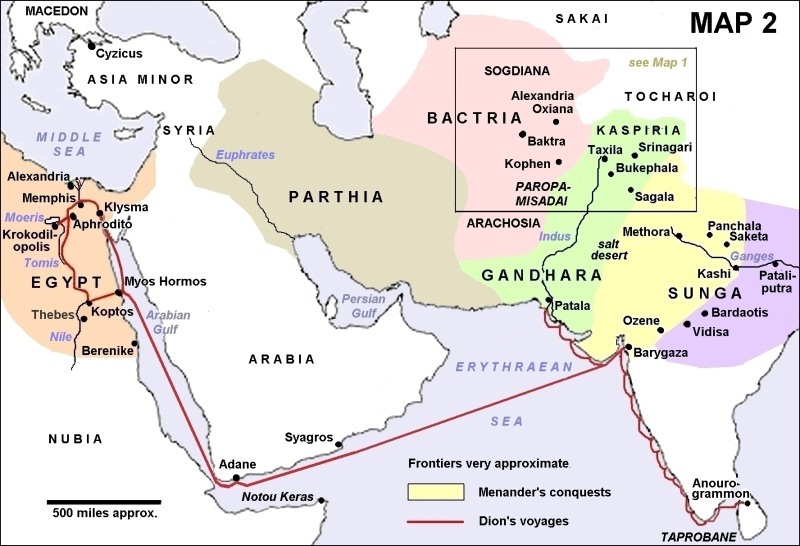

At the same time I have included as much fact as I can. Menander, for instance, the greatest of the Indo-Greek kings, was indeed held in deep respect by his subjects. While the career and character of my protagonist Dion are fictional, there really was a Greek of that name in the right place at the right time. The inscribed pillar dedicated by his son Heliodorus to the great god Vishnu stands near Bhopal to this day. The tapestry used by Dion as a saddlecloth (see the title picture) was recently found in a grave near Khotan in China, recycled into a pair of trousers and still clothing the legs of a contemporary skeleton. In the Karakorams, all five of the passes which Dion crossed lie some 18,000 feet above the sea; small wonder that, a little later, the first Chinese to venture this way called them the Greater Headache Mountains. Those parts of the cities of Alexandria Oxiana and of Taxila that have been excavated were much as here described. The bad jokes in Chapter 6 are genuine Greek ones. And so the list could go on.

At the time this story took place — between about 160 and 125 BC — south and central Asia, like everywhere else, were very different from now, and a few words of explanation may help.

- The distinctive multiple-caste system of modern India had not yet evolved. At this date, the only social stratification was that common to most cultures, with four loose rankings.

- Buddhism and Hinduism, having a certain amount in common, were not as mutually exclusive as religions tend to be today.

- The word ‘Hindu’ was originally a geographical or ethnic label. Only from medieval times was it also applied to the religion; hence my use of ‘Brahmin’ instead.

- By ‘Greeks’ in Bactria and Gandhara I mean those descended from original settlers. Most of them were in fact Macedonians by origin, which ethnically is not quite the same.

- ‘Yona’ — that is, Ionians — was what the Indians called the Greeks, but I use the word only in direct speech from the mouths of Indians.

- Alexander the Great named some eighteen cities after himself, and with the single exception of the great Alexandria in Egypt (in Chapters 5 and 6) the Alexandria in this tale is always Alexandria Oxiana in present-day Afghanistan.

- One thread in the story is the development of some basic technologies. When and how these were transferred from one part of the Old World to another is not on record; but my fictitious account does not conflict with what evidence there is.

- A stade was roughly an eighth of a mile, a cubit was a foot and a half.

This territory and this subject matter, being strange to many readers, seem to demand illustrations. If you want to know where you are, you will find maps and a gazetteer at the end of this introduction. If you are interested in what the machines were like, you will find modern pictures there too. And if you like mental images of the characters, you will find in the text a number of Bactrian and Indo-Greek portraits of the period — including some from the finest coins ever minted by the Greeks — to show how they saw themselves and, occasionally, how they were seen by Indians.

Anyone familiar with Kipling’s Kim will recognise that I owe it much. The issues it raises of identity and allegiance, combined with its vivid first-hand picture of the diversity of India, make it, in my view, one of the best novels of all time. Its narrative and descriptive genius, however, is far beyond my power to emulate.

I am also indebted to Ben, Hilary, Jerry, Paul and Pryderi for commenting on my draft, to Gardner for guiding my faltering footsteps along the Middle Way, and to Jonathan for everything.

October 2014

Gazetteer of ancient place-names and their modern equivalents

| Adane | Aden, Yemen |

| Alexandria Oxiana | Ai Khanoum, Afghanistan |

| Anourogrammon | Anuradhapura, Sri Lanka |

| Aphrodito | Atfih, Egypt |

| Arabian Gulf | Red Sea |

| Arachosia | Southern Afghanistan |

| Bactria | Northern Afghanistan / Tadjikistan |

| Baktra | Balkh, Afghanistan |

| Bardaotis | Bharhut, Madhya Pradesh, India |

| Barygaza | Bharuch (Broach), Gujarat, India |

| Batanagra | Leh, Jammu & Kashmir, India |

| Berenike | Madinet-el-Haras, Egypt |

| Bukephala | Jalalpur, Punjab, Pakistan |

| Chaurana | Khotan, Xinjiang, China* |

| Cyzicus | Belkiz Kale, Turkey |

| Emodon | Kunlun Range, Xinjiang, China* |

| Erythraean Sea | Indian Ocean |

| Gandhara | Pakistan / Punjab, India |

| Hydaspes | River Jhelum, Kashmir, India / Punjab, Pakistan |

| Hyphasis | River Beas, Himachal Pradesh / Punjab, India |

| Imaus | Karakoram Range, India / Pakistan |

| Kashi | Varanasi (Benares), Uttar Pradesh, India |

| Kaspiria | Kashmir, India |

| Klysma | Suez, Egypt |

| Komedai | Pamir Range, Tadjikistan |

| Kophen | Kabul, Afghanistan |

| Koptos | Qift, Egypt |

| Krokodilopolis | Madinet-el-Faiyum, Egypt |

| Labokla | Gagangear, Jammu & Kashmir, India |

| Lithinos Pyrgos | Tashkurgan, Xinjiang, China* |

| Maurya | empire ruling much of India to c.185 BC |

| Memphis | Mit Rahina, Egypt |

| Methora | Mathura, Uttar Pradesh, India |

| Middle Sea | Mediterranean |

| Moeris | Faiyum Oasis, Egypt |

| Myos Hormos | Quseir al-Quadim, Egypt |

| Notou Keras | Cape Guardafui, Somalia |

| Nubia | Sudan, approximately |

| Oxus | River Amu Darya, Afghanistan / Tadjikistan |

| Ozene | Ujjain, Madhya Pradesh, India |

| Panchala | Farrukhabad region, Uttar Pradesh, India |

| Paropamisadai | Hindu Kush Range, Afghanistan / Pakistan |

| Parthia | Iran and Iraq, approximately |

| Patala | Thatta, Sindh, Pakistan |

| Pataliputra | Patna, Bihar, India |

| Ptolemaios Potamos | Nile-Red Sea canal, Egypt |

| Rhapta | Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania |

| Sagala | Sialkot, Punjab, Pakistan |

| Sakai | Scythians, people of central Asian steppes |

| Saketa | Ayodhya near Faizabad, Uttar Pradesh, India |

| Seres | people of China proper |

| Sogdiana | Uzbekistan / Tadjikistan / Kyrgyzstan |

| Soita | Yarkand, Xinjiang, China* |

| Srinagari | Srinagar, Jammu & Kashmir, India |

| Sunga | Indian empire following Maurya |

| Syagros | Ras Fartak, Yemen |

| Taprobane | Sri Lanka |

| Taxila | Taxila, Punjab, Pakistan |

| Thebes | Luxor, Egypt |

| Tocharoi | people of Taklamakan Desert, Xinjiang, China* |

| Tomis | Bahr Yusuf canal, Egypt |

| Vidisa | Vidisha, Madhya Pradesh, India |

| Yona | Indian name for Greeks |

|

|

Machines

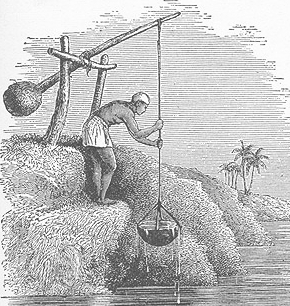

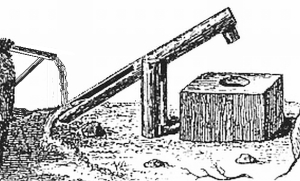

Tula / kelon

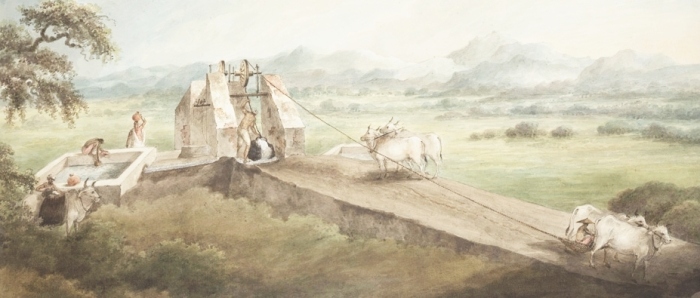

Jhula

Cam’maca

Baiga

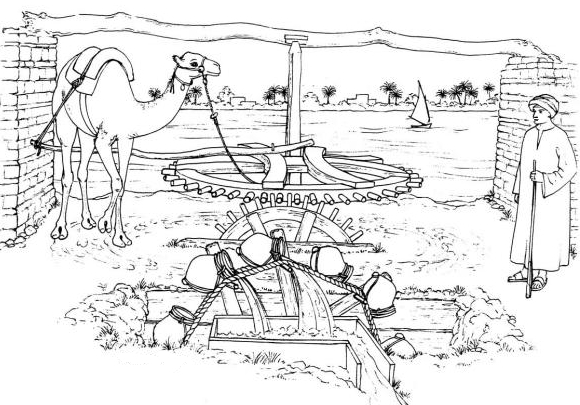

Halysis / chain lift

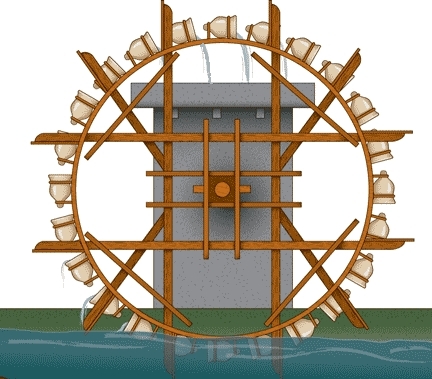

Tympanon / bucket wheel

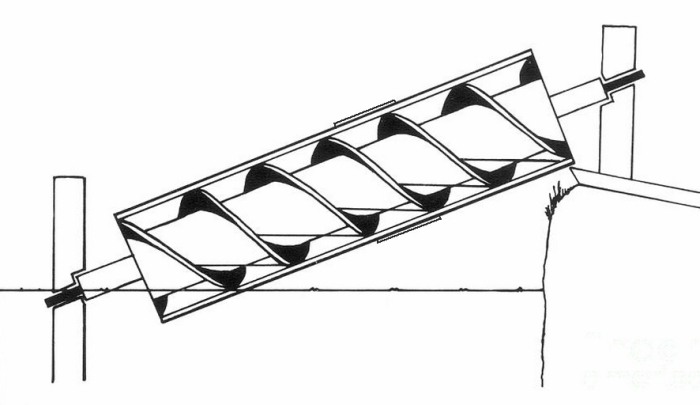

Kochlias / snail

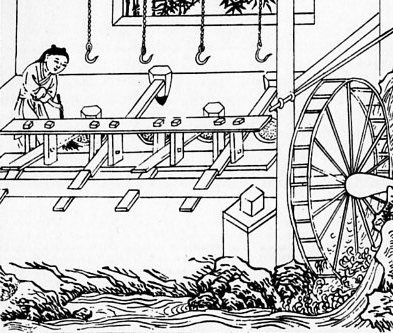

Rice pounder

Cane crusher