Ashes Under Uricon

On Wenlock Edge the wood’s in trouble;

His forest fleece the Wrekin heaves;

The gale, it plies the saplings double,

And thick on Severn snow the leaves.

’Twould blow like this through holt and hanger

When Uricon the city stood:

’Tis the old wind in the old anger,

But then it threshed another wood.

Then, ’twas before my time, the Roman

At yonder heaving hill would stare:

The blood that warms an English yeoman,

The thoughts that hurt him, they were there.

There, like the wind through woods in riot,

Through him the gale of life blew high;

The tree of man was never quiet:

Then ’twas the Roman, now ’tis I.

The gale, it plies the saplings double,

It blows so hard, ’twill soon be gone:

Today the Roman and his trouble

Are ashes under Uricon.

A. E. Housman (1859-1936)

Wenlock Edge, from A Shropshire Lad

Foreword

Four years ago I wrote a story called Those Old Gods, which tells of two boys and their discoveries — and self-discovery — while excavating a Roman-British temple near Bath. That tale is set in the present day. Here now is its ancient counterpart, the tale of those who patronised the very same temple in Roman times. None the less Those Old Gods, although it falls chronologically so much later, is perhaps best read first; but it does not greatly matter.

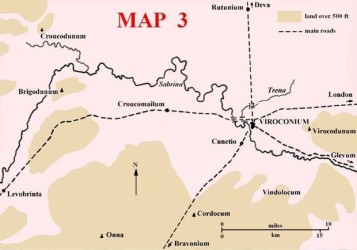

The present story unfolds, for the most part, at the town then known as Viroconium Cornoviorum, whose site near the modern Shrewsbury is marked these days only by the tiny village of Wroxeter and the spectacular remnants of its Roman baths. From the Severn plain nearby there rises, like a whale leaping from the sea, the isolated hill of the Wrekin. On its summit lies an Iron Age hill-fort, once a centre of the tribe of the Cornovii, that preceded the Roman town. Both names, Wrekin and Wroxeter, derive from the British-Latin Viroconium, which antiquarians formerly and mistakenly spelt as Uricon.

Among those antiquarians was A.E. Housman, whose famous poem has supplied my title. He was an interesting if melancholy character, not only gay but unfulfilled, who knew full well that no generation, as it comes and painfully goes, has a monopoly of grief and trouble. “The tree of man was never quiet,” as he put it; “then ’twas the Roman, now ’tis I.” Howright he was. There is little new, in this respect, under the sun.

None the less it is not easy for us, acclimatised to modern psychological constructs, to understand the Romans’ attitude towards homosexuality. Society was, up to a point, highly permissive. There were of course laws, buttressed by public opinion, against rape and to protect the free-born young. Beyond that, sexual activity between males involved, in principle, no shame or disgrace whatever, and it was widespread. Males were expected eventually to marry and procreate, and usually they did. But, from the evidence not only of upper-class literature but of mis-spelt graffiti scrawled by the lower orders, it is perfectly clear that they were free, indeed almost expected, to find pleasure in both sexes. The Romans, moreover, like the Greeks, had no word for sexual orientation as such, because they simply did not think of people as being gay or straight or bisexual. What mattered was not what you were, but what you did, and with whom.

This was the area where the Romans, for all their permissiveness, suffered from a great hang-up which is explored in the following pages. But it must be remembered that this hang-up was largely limited to the traditional culture of Rome and Italy. The make-up of Rome’s vast cosmopolitan empire, once it had spread around the whole circuit of the Mediterranean and far up into Europe, was endlessly varied. Away from the centre, conventions were not necessarily the same. Much depended on how far pre-existing local custom was overlaid by Roman custom and even by Roman law. And as the grip of Christianity tightened, yet another brand of morality, disapprovingly rigid and prudish, took over.

Thus in Roman Britain, at the very fringe of the empire, long-established native attitudes to sexuality were confronted by imported ones — not only by the traditional Roman attitude but ultimately by the Christian. What might have been the situation here is one of the themes of this tale. I say ‘what might have been’ because hard evidence of the British outlook is minimal. But, by extrapolating forwards from what is recorded of earlier Celtic custom and backwards from the oldest Welsh laws, I have made an informed guess. This is, after all, a work of fiction. But in another sense, as an attempt at a portrait of a fascinating age, it is also factual. The setting is real, and while the central characters are fictitious, all the emperors, most of the governors, generals and churchmen, and some of the minor players, did actually exist. The background, essentially, is history.

But what is history? I am not thinking of definitions like the glorious one offered by the schoolboy in Alan Bennett’s play, that history is just one fucking thing after another; although those overwhelmed by events at the end of Roman Britain would no doubt have agreed with it. What I mean is that all history is open to interpretation, and none more so than in this ill-recorded period. This is not wholly unwelcome, for it allows licence to offer my own interpretation. I confess, too, that to suit my fell purposes I have taken, as experts will spot, a few deliberate liberties with detail.

I have regularly employed one Latin term which can hardly be translated. The civitas was the major Roman unit of local government, meaning the territory which (in our case) had belonged to the pre-Roman tribe of the Cornovii, whose centre was Viroconium. The closest modern analogy is the county — Shropshire, for example, with its county town of Shrewsbury. But the civitas of the Cornovii was far larger than Shropshire, for it embraced adjacent counties too, as well as a fair slice of central Wales. The Cornovii in their turn were but one civitas in the province of Britannia Prima, whose capital was Corinium (Cirencester). There were four provinces in Britain at the time, each with its own governor, and over all four governors was the Deputy Prefect, based at London and answerable to the Prefect of the Gauls.

The portrait on the title page is a genuine Roman one, and although it comes from Egypt and dates from two centuries before our period, it is much as I imagine Docco, our protagonist, looked at the point when first we meet him. The story spans the years between AD 360 when he was about to turn twelve and 411 when Roman Britain had collapsed around his ears. To help readers of historical bent, I have added to the title of each chapter the date when its events took place.

If you have no Latin, it does not matter a hoot, for all quotations are translated. Those at the chapter heads are from late Roman authors, many of which themselves inspired aspects of the plot. But all those translated in italics in the text are from Vergil, whose standing in those days, even in distant Britain, was immense, higher even than Shakespeare’s is with us today. Some translations are wholly my own, others draw to some degree from those — notably the incomparable Helen Waddell — who have gone before. A geographical note, following immediately after this foreword, converts ancient place-names into modern equivalents and locates the British ones on maps.

This tale sees the light of day at a not inappropriate time. One of its threads is slavery, and we have just celebrated the bicentenary of the abolition, on 25 March 1807, of the slave trade in British territories. Another of its themes is the spread of Christianity, and last year we marked the 1700th anniversary of the acclamation, at York on 25 July 306, of Constantine the Great as emperor of Rome; an event which proved, for better or for worse, one of the most fundamental in the whole history of Christianity, of Europe, and indeed the world.

My thanks are due to the multitude of unwitting authors from whom, in the course of much magpie reading, I have filched facts, fancies, and even phrases; notably Mary Renault, Ellis Peters, and John Julius Norwich. As usual, too, I owe a huge debt to Jonathan for being with me, and to Ben, Chris, Hilary and Pryderi for reading drafts and making many wise comments. And it is to Pryderi that I dedicate the story, in gratitude for his broad-mindedness, his insights, and his support.

Ante diem IV Kal. Mai. MMVII

Geographical note

To keep this section available for ready reference, click here to open it in a new page

Should the historical novelist use ancient place-names or modern? The choice is a tricky one. To most readers, York and Bath will mean more than Eboracum and Aquae Sulis. Few, on the other hand, even present-day Britons, have heard of Wroxeter or Leintwardine, and Viroconium and Bravonium impart a finer sense of period. For better or worse, therefore, I have mostly plumped for the ancient names, in latinised rather than in native spelling. But where there are obviously similar English forms, ancient place-names like Roma, Parisii, Londinium and Britannia seem over-pedantic. The same applies to personal names like Constantinus and Vertigernus.

One special case, however, calls for comment. To the Romans, Ireland was Hibernia, and its inhabitants were Scotti, Scots. It was not until well after our period that Irish settlers gave their name to what is now known as Scotland. The Irish crop up frequently in this story, and it seems to me that, even with this warning, to call them Scots would invite confusion. Irish they therefore are, living in Ireland.

The following list identifies such ancient names as are not blindingly obvious. Most are certainly genuine. A few are probably or possibly so. But where the ancient ones are not on record at all, I have fabricated them by working back from more recent names, and these are marked with asterisks. After the list are three maps, at different scales, which mark all the British and Irish places and peoples mentioned.

| Abona | River Avon (Bristol) |

| Abonae | Sea Mills (Avonmouth) |

| Aquae Sulis | Bath |

| Armorica | Brittany, France |

| Attacotti | Irish people settled in south-west Wales |

| Bithynia | Roman province, north-west Asia Minor |

| Bononia | Boulogne, France |

| Bravonium | Leintwardine, Herefordshire |

| Brigantes | British tribe/civitas centred on Yorkshire |

| Brigodunum* | The Breiddin, Powys |

| Burdigala | Bordeaux, France |

| Camulodunum | Colchester, Essex |

| Canovium | Caerhun, Conwy |

| Condate | Northwich, Cheshire |

| Cordocum* | Caer Caradoc, Shropshire |

| Corinium Dobunnorum | Cirencester, Gloucestershire |

| Cornovii | British tribe/civitas centred on Shropshire |

| Cravodunum* | Great Orme, Conwy |

| Croucodunum* | Llanymynech Hill, Powys |

| Croucomailum* | Cruck Meole, Shropshire |

| Cunetio | Cound, Shropshire |

| Deceangli | British tribe centred on Flintshire |

| Demetae, Demetia | British tribe/civitas of Dyfed, south-west Wales |

| Deva | Chester, also River Dee |

| Deva Sea | Liverpool Bay |

| Dobunni | British tribe/civitas centred on Gloucestershire |

| Dubris | Dover, Kent |

| Dumnonii | British tribe/civitas of Devon and Cornwall |

| Durotriges | British tribe/civitas centred on Dorset |

| Eboracum | York |

| Fanum Maponi* | Nettleton, Wiltshire |

| Ganganorum Promontory | Braich y Pwll, Gwynedd |

| Gaul | France, approximately |

| Glevum | Gloucester |

| Hippo | Bone, Algeria |

| Iceni | British tribe/civitas centred on Norfolk |

| Inberdea | Wicklow, Ireland |

| Isca | Caerleon, Gwent |

| Isca Dumnoniorum | Exeter, Devon |

| Isurium Brigantium | Aldborough, Yorkshire |

| Laigin | Leinster, Ireland; later Llŷn Peninsula, Gwynedd |

| Levobrinta | Forden Gaer, Powys |

| Lindum | Lincoln |

| Luguvallium | Carlisle, Cumbria |

| Mailobrunnia | The Malverns, Worcestershire |

| Mediolanum | Milan; also Whitchurch, Shropshire |

| Mona | Anglesey |

| Moridunum | Carmarthen, Dyfed |

| Nemetobala | Lydney, Gloucestershire |

| Noviomagus | Chichester, Sussex |

| Oaxes | fictional river |

| Oboca | River Avonmore, Co. Wicklow |

| Octapitarum | St David’s Head, Dyfed |

| Onna* | Linley, Shropshire |

| Pagenses | part of Cornovii in central Wales (hence Powys) |

| Pannonia | Roman province centred on Hungary |

| Picts | people of highland Scotland |

| Pons Aelius | Newcastle-upon-Tyne |

| Ratae | Leicester |

| Rutunium | Harcourt Park, Shropshire |

| Rutupiae | Richborough, Kent |

| Sabrina | River Severn |

| Sabrina Sea | Bristol Channel |

| Salicinum* | Helygain, Halkyn, Flintshire |

| Salinae | Middlewich, Cheshire |

| Saxons | people of coastal Europe, N Holland to Denmark |

| Scythia | Ukraine, roughly |

| Segontium | Caernarfon, Gwynedd |

| Silina | Isles of Scilly, Cornwall, then a single island |

| Silures | British tribe/civitas in South Wales |

| Tamium | Cardiff |

| Trena | River Tern, Shropshire |

| Treveri | Trier, Germany |

| Truscolenum* | Mynydd Parys, Anglesey |

| Uí Failgi | Irish tribe centred on Co. Kildare |

| Uí Garrchon | Irish tribe centred on Co. Wicklow/Kildare |

| Varae | St Asaph, Denbighshire |

| Vebriacum | The Mendips, Somerset |

| Vectis | Isle of Wight |

| Venedotia | Gwynedd |

| Venta Belgarum | Winchester, Hampshire |

| Venta Silurum | Caerwent, Gwent |

| Vertis | Worcester |

| Verulamium | St Albans, Hertfordshire |

| Vindolocum* | Wenlock Edge, Shropshire |

| Virocodunum* | The Wrekin, Shropshire |

| Viroconium Cornoviorum | Wroxeter, Shropshire |

| Vogius | River Wye |

| The Wall | Hadrian’s Wall, between R Tyne and R Solway |

Part 1: Boy

Chapter 1. Identity (360)

Haec dum vita volans agit,

Inrepsit subito canities seni

Oblitum veteris me Saliae consulis arguens:

Ex quo prima dies mihi

Quam multas hiemes volverit et rosas

Pratis post glaciem reddiderit, nix capitis probat.

Numquid talia proderunt

Carnis post obitum vel bona vel mala,

Cum iam, quidquid id est, quod fueram, mors aboleverit?

Life flitted by, old age crept on. Suddenly I was an old man, forgetful of how it all began. I was born when old Salia was consul, and my white hair tells how many winters have passed since then and how many times, after the frosts, flowers have re-decked the fields. What will all this mean, for good or ill, when my flesh is lifeless, when death has destroyed whatever I have been?

Prudentius, Preface

Boys of eleven rarely bother their heads with wondering who they are. But that is what I found myself doing, my very first day at Nonius’ academy. Its atmosphere was sedate and intellectual, a far cry from my elementary school with its repetitive round of reading, writing and arithmetic, its harassed and impatient teacher, and his relentless use of the cane. Nonius, by contrast, entered the classroom with grave dignity. He reverently opened the great book upon his desk. He cast a slow and comprehensive eye over the twelve boys and five girls of his new intake as they sat silent and mildly scared in these strange surroundings. And then he read.

Vergil was new to me, and the Aeneid struck an instant spark in my receptive young soul. Never will I forget Nonius intoning its opening lines:

Arma virumque cano, Troiae qui primus ab oris

Italiam fato profugus Lavinaque venit

Litora — multum ille et terris iactatus et alto

Vi superum, saevae memorem Iunonis ob iram.

Of arms I sing, and the man who first, fate-exiled from the land of Troy, reached Italy and the Latin shore; a man much buffeted on land and sea by the power of the gods, on account of ruthless Juno’s unforgetting wrath.

Vergil was singing the glory of imperial Rome, and there and then his song enslaved me; not merely the sonorous language, not merely the stately rhythm, but the great unfolding story of Aeneas himself, the battered soldier who, carrying his aged father on his back, had from the flames of dying Troy led a despairing band of refugees to found a new nation in the west. Aeneas was a hero, the hero from whom Rome herself had sprung, and Vergil’s epic rang in my ears like a battle cry. It was surely this, and the likes of this, that had inspired us to conquer the world. When school was over I avoided my friends and marched straight home, head high and patriotic blood pumping through my veins, proud to be a Roman.

But once home, as I passed the niche with its diminutive images of our household gods, I stopped, as I always did, to pay them my respects: Donnotarvus who looked after our cattle, cross-legged Cernunnos the guardian of the heads of men, the three Mothers representing fertility, sustenance and compassion, and the naive little Hooded Ones, the homely dwarves who stood for our family togetherness. Doubts, at that point, began to nibble at my new-found certainty. How did these very British beings square with the mighty gods of Olympus who had so buffeted Aeneas in his wanderings? Juno said nothing to me. I knew of course who she was — the bitchy wife of Jupiter, the boss of the Roman pantheon — and she was there in her official place in the Town Hall, honoured once a year in tedious civic ceremonial. She was a Roman formality, and she was not mine. Yet how could I feel Roman — how could I be Roman — without acknowledging her and her colleagues? I asked my own gods, and my mind began to clear.

I was not really Roman after all, was I? I was not one of the conquerors. I was British, and the British, in hard fact, were the conquered. The Romans were different from us. They were not our enemies, not now, though they had been long ago. But they were our masters. Benevolent they might generally be, but they were still our masters.

Their influence was all around. Latin was the invariable language of school, of literature, of the polite society to which we hardly belonged, of the army, of the law, of the government and its thousand bureaucratic tentacles which so infuriated my father. Latinspilled over into everyday life in all manner of details. In the wording on coins, for example — DN CONSTANTIVS PF AVG, they said, ‘Our Lord Constantius, dutiful, happy and august,’ which one took with a sizeable pinch of salt. Or in dates — I had been born on the sixth day before the Kalends of September in the consulship of Salia and Philippus, or (if you prefer) in the twelfth year of the same dutiful and happy Constantius, or (if you are pernickety) in the 1101st year since the founding of Rome.

But the fact that Roman practice pervaded our life did not make us Roman. We might know Latin, but we talked nothing but British among the family, and to our gods, and with our neighbours, and in the shops, and on the farm where some of the hands had no Latin at all. Never did I speak Latin to my friends, except for special effect. Sometimes we made a day of it and scampered the three miles to Virocodunum where, three full centuries before, our tribe of the Cornovii had made its last stand against the invaders. We would slog up the slope to the ramparts of the old hill-fort, and there we would play our war-games, childishly re-enacting the siege. Most of us preferred the role of Britons, dying in proud but vain defence of our freedom. But some were willing to act as Romans simply because they liked to be on the winning side. The Romans always won. That was what history decreed. Yet when an infant Roman soldier fell and grazed his knee, it was in British that he blubbered, and in British that his enemies comforted him.

Three centuries is a long time. We were Roman citizens now, all of us who were free-born. In our distant corner of the sprawling empire we were prospering, usually, in our quiet and modest way. We owed allegiance, usually, to the emperor in far-off Rome or Constantinople or wherever he happened to be. We paid our taxes to him, and in return he defended us against our enemies; or rather he was supposed to, but far from always did. Another of our war-games was to man the town’s skimpy and half-rotten wooden palisade set on an earthen mound, local Britons shoulder to shoulder with a handful of Roman troops, fending off baying hordes of Irish barbarians who had outflanked the meagre coastal garrison and come marauding far inland. This game worried me. I could not readily cast myself as Irish, for the Irish were our present foes. But while I happily slaughtered Romans in make-belief at the hill-fort, I was uncomfortable at slaughtering Irish, even in make-belief, from the town walls. I was uncomfortable at calling them barbarians at all; for Bran was Irish, and Bran was not a barbarian. He was my friend.

More accurately, Bran was of Irish descent. His great-great-grandfather had been bought by my great-great-grandfather back in the days when Irish traders had ferried their own people over the sea to sell to us as slaves. The boot was now on the other foot, for the Irish in their marauding were enslaving many more of us than we of them. Of the current members of Bran’s family, Tigernac ran the house and attended to my father, Roveta presided over the kitchen and looked after my mother, and their son Bran was my slave. Not my personal property — I was still too young for that — but for all practical purposes he was mine. He was three years older than me, tall, handsome, fair-haired and loose-limbed, and a very special companion. My relationship with my ordinary friends was straightforward, for we were equals. My relationship with Bran was different, for we were not equals, and we both knew it. But I made us as equal as I could. My father had made it quite plain, as far back as I could remember, that it is not a slave’s fault that he is a slave. It is his misfortune. He is still a human being. And I took the advice to heart.

Pondering over my identity, that afternoon, saw me as far as the bath. There I found Bran coming up from the stoke-hole. He asked at once how my day had gone, and as I stripped and lay down for him to oil me I told him all that I had heard about the Aeneid, and recited what little I could remember. He understood my excitement. He was, for a slave, well-educated. He could read and write. His lessons had been paid for by my father, who had no truck with the philosophy of keeping slaves ignorant, and Bran’s British and Latin were as good as mine. More than that; his forebears had passed down the Irish language and the Irish tales, so that he was trilingual. And he was sensitive and intelligent. He was well qualified to help in my perplexity.

“Bran,” I said when we had progressed to the hot room and I was getting up a sweat. He had shed his tunic and was wearing only drawers and, as protection against the searingly hot floor, wooden-soled bath sandals. “Bran, what are you?”

Naive questions always made him tease me, which could be exasperating. I felt he was treating me as a brat; which no doubt I was.

“Your slave, master.”

“Dammit, Bran, don’t call me master. I’ve told you a thousand times. Why can’t you call me Docco? And what I mean is, what do you feel you are? Irish? British? Roman?”

“I feel whatever you feel you are.”

Despite my tender age, I thought I could understand. He did not know what answer I expected, and a slave, even a slave who is a friend, is anxious to avoid offence. But I persevered.

“But you must have your own ideas. Forget about me. If I died tomorrow, what would you feel?”

“Desolated.”

Frustrating again. It was still not the sort of answer I was after. But he seemed to mean it. He did mean it. We were friends.

“Well, thanks. And I’d be desolated if you died. Of course I would. But would you feel more Irish if you didn’t have me to bother about?”

He hesitated, at last giving it serious thought.

“No,” he said. “I’ve never known anything but this.” He waved his hand vaguely around. “I’d never want to go to Ireland. I doubt they’d understand my Irish, for a start. And life’s so basic there, from all I hear. None of the comforts of Britain. Of Viroconium. Of this house. None of the … well, of the civilisation. And then the Irish are your enemies. Enemies of Britain, of Viroconium, of this house. I could never be your enemy. Are you ready to be scraped?”

I nodded and turned on to my front, and he got busy on my shoulders with his strigil. As he worked methodically down, I wondered — it had never occurred to me before — who scraped Bran in the bath. I must ask him, but not now. This conversation was too important.

“But if you went back to Ireland,” I objected, “you’d have the freedom you don’t have here. Wouldn’t you swap our civilisation for that?”

He stopped scraping. “Freedom,” he said softly, “is what you do with what’s been done to you.”

As I thought that over, Bran resumed his scraping. He had now reached my buttocks, and it suddenly struck me that he never oiled inside my crack, or opened it to scrape inside, as my other friends and I did to each other when we bathed together. That too had not occurred to me before.

“Did you know,” he continued, “that three years ago, after my grandma died, your parents offered my parents their freedom?”

This was news to me, and very interesting. “No. I didn’t. And they turned it down?”

“Yes. They chewed it over, and included me in their talk. They’ve met plenty of other people’s slaves, they said — not just slaves of Britons, but of Romans who’re passing through — and they know how well placed we are. They know that when they grow old you’ll look after them, just as you did my grandparents, and theirs. If we stayed on in your service as paid servants we wouldn’t be any better off, because you already give us all we need. And if my father took up some trade, life would be thick with uncertainties. Don’t wriggle.” He was scraping my feet, and tickling. “They appreciated your parents’ offer. It was typical of them, they said. But they turned it down … There, that’s your back done. Roll over.”

I rolled over. By this stage of the proceedings, what with the sensuous stimulation of my skin, I usually had an erection. It had started a year or so before and, while it never embarrassed me a whit, at first it had embarrassed Bran, though by now he was used to it. But today our talk was too engrossing, and nothing stirred.

“But that was your parents’ decision, really,” I said. “Not yours. If you were offered your freedom, would you take it?”

“No.” He was quite definite. “Not if it was just a reward for good service. As it was when it was offered to my parents.”

Even I recognised, young though I was, that he had left something important unsaid. I was about to probe further, but he went on.

“You see, Docco, your life and mine … they’re intertwined.”

He wiped the gunge of sweat and dirt and oil off the strigil with a towel, and scraped carefully around my little tool and balls without touching them. He never touched them when oiling me, either.

“That’s what I meant when I said that I feel I am whatever you are. And I reckon you’re not Roman. Not wholly Roman, thank goodness. Partly, yes — otherwise you wouldn’t be having a bath like this. But you’re more British than anything, whatever Vergil’s been putting in your head. Did Nonius say who Vergil was writing for?”

I thought back and remembered it word for word.

“He said that he was writing for the Romans, at the beginning of the empire. But that what he wrote was a beacon to guide the ages to come. The voice not only of Rome but of all mankind.”

“There you are, then. You’re a Briton, basically, and therefore part of all mankind. Right, you’re done.” He had reached my ankles. “We’d better get a move on. Your father will be wanting his bath, and I’ve got to help in the kitchen.”

I had a quick wallow in the hot tub to rinse off, and Bran dried me, followed me to my room to find me a clean tunic, and disappeared. For an hour I lay on my bed, thinking gratefully over what he had said, and speculatively over what he had not. Tomorrow, I reckoned, I had two very particular questions to put to him. Then an idea swam into my head, and I wandered along to the kitchen. Little did I know it, but that idea was to set my friendship with Bran on a new path.

Later, in the dining room, there were only my father and myself for dinner, for Mamma was poorly. She often was, these days. She had had a bad time, apparently, when I was born, and had nearly died. The midwife had told her that another child would certainly be her death, which was why I had no brothers or sisters; any more than Bran did. She had got over that, but for the last few years had been ailing with some other illness, nobody knew what.

Tad too asked how things had gone at school, and I told him what I had told Bran. He chuckled.

“Arma virumque cano! So Vergil made you feel proud and Roman?”

“Yes, very. But only for the time being. Then I began to feel more British than Roman. What do you feel you are, Tad?”

“The same, Docco. Exactly the same. People come in a whole range of types, you know. Like the colours in a rainbow, one shade merging into the next. If you take the full-blooded Roman as the red end, I’d say that we were nearer the other end. At blue, perhaps. We’ve adopted some of our masters’ habits. Without them, we wouldn’t have this.” He tapped the jar of fish sauce with his knife. “Or this.” He looked at the wine cup in his hand. “If it wasn’t for them, we’d have nothing to drink but beer. But our cousins up in the mountains have precious little contact with the Romans, and they’re still right at the violet end. No fish sauce. Nothing but beer.”

“But why are we so different, Tad? I’ve never met a Roman, a real Roman. I mean, how are we different? Apart from language?”

“Well, we treat people differently, for a start. For instance, a Roman wife is very much under her husband’s thumb. With us, husband and wife are equals. Do you reckon your Mamma’s under my thumb?”

I grinned. “No!”

“I hope not. Nor me under hers, either. And Romans are rigid. They live by the rule-book. They put their own dignity above other people’s. Real Romans, that is. I’ve met plenty of Gauls and Spaniards, say, who’re more Roman than we are but are still fine and easy to get on with. But real Romans … not necessarily from Rome or even Italy, but people who subscribe to traditional Roman ways … well, I’ve never yet met one I really liked. Don’t get me wrong. I’m sure there are good Romans, just as I know there are bad Britons. But I reckon the closer a Roman is to the red end, the colder he’s likely to be. Harder. More unfeeling. The real Roman exploits people.”

He interrupted himself to pick bones out of his salmon.

“Whereas we care, or we try to. We try to treat people as individuals. To respect their feelings, and their dignity. Take your own case. You’ll come of age when you turn fourteen. If you were a girl you’d come of age at twelve. After that, boy or girl, you own your own property. After that, if I wallop you, you can take me to court. After that, you can leave home if you want — I hope you won’t, but you can. After that, your personal life is your own affair and you can marry without asking me.

“But if we were Romans, you’d be under my authority indefinitely, either until I died or I released you. In fact in strict law — I think I’m right in this — I could even kill you with impunity. You’d have no property rights. You’d need my permission to marry, and your wife would be under my authority, although you could have a mistress, or even several, and you could ditch them as you saw fit. But look at what British law says about that — if a man sleeps for only three nights with a girl and then ditches her, he has to pay her compensation. Three oxen, I think it is. Don’t forget that, Docco” — he wagged a mock-serious finger at me — “when you’re old enough. So which of those approaches appeals to you?”

“Ours. No argument.”

“Agreed. I’m not at all surprised you’ve fallen for Vergil. He’s great stuff, so long as you keep him in context. Nor that you got flushed with Roman patriotism. But you’ve been pretty smart at recovering your Britishness. How come?”

“I talked to the household gods,” I said, and saw approval in Tad’s face. “And then I talked to Bran.”

Bran had been in the dining room all along, waiting on us in his usual silence. Tad looked at him in approval too.

“Good for you both. Why do you take that line?” he asked Bran.

“Sir, because no Roman, from all I hear, would treat his slaves as you treat us.”

“Thank you. Well, let’s take that a step further. Today’s a milestone for Docco, a special day. And so it’s a special day for us too. First of all, Bran, would you give Docco some wine, please? Do you think it should be watered?”

“I think he could take it neat.”

Bran was straight-faced. He knew my capacity, having often enough given me neat wine in the kitchen, surreptitiously.

“But in moderation,” he added austerely.

“Very well then, neat but in moderation. Thank you. And now would you care to lie with us and join us with a cup of your own?”

“If you’d excuse me, sir, I’d rather not. I’ve already had wine this evening.”

“And,” I could not help interjecting, “a large cup of it, too.” I was feeling happily mischievous.

“How do you know?” asked Tad, surprised.

“I waited on them in the kitchen while they ate.”

Tad bellowed with laughter. Even Bran wore a broad grin, and I had a third question for him.

On the way to bed I passed the household shrine. The Romans were welcome to their own gods, so long as I had mine. I said my thank-you and left them two olives I had saved from dinner. Next morning the food would be gone. I used to think that the gods ate it. Nowadays I suspected that Roveta tidied it away when she did her housework, though I had never seen her at it.

That day — those few days — lie more than fifty years in the past. At various stages in my life I have relived them, before half-forgetting them again. My hair may now be white, but reliving them once more has brought the detail back as clear as if it were yesterday, for they were the time when I began to grow up, the time when my path through life began to be defined. What it will all mean, for good or ill, when death has destroyed whatever I have been, is more than I can say.

Chapter 2. River (360)

Amnis ibat inter arva valle fusus frigida,

Luce ridens calculorum, flore pictus herbido.

Through the meadows ran a river; down the airy vale it wound,

Smiling mid its radiant pebbles, decked with flowery plants around.

Tiberianus, Amnis ibat

Life was good, at that age. Next day, because Nonius was a traditionalist who kept Saturday as his day of rest rather than the new-fangled Sunday, there was no school. I spent the morning with the gang of my three closest friends.

We roamed and larked as eleven-year-olds always have and always will. We went out to the dam where the aqueduct takes off from the stream, and threw flowers into the water — a poppy, a daisy, a dandelion, a cornflower — and followed them as they drifted the mile to the town, and ran shrieking through the gate to see which should arrive first at the reservoir inside the walls. We watched the waterwheel turning at the northern mill and poked our noses into the dark and dusty interior and annoyed the miller. We kicked an inflated bladder around the cattle market until the superintendent chased us off. We dodged through the crowded streets, stopping here and there to watch the weavers at their looms, or the bronzesmiths fashioning brooches, or the glass-blowers and enamellers, or the blacksmiths at their clanging forges. We spent our small change on bread and cheese and ate it squatting in the market colonnade, in an empty space not yet taken by a stallholder, while we played knucklebones. We held a little competition, in a back street, to see how high we could pee up a wall. We passed the temple of Epona bedecked with horses’ heads and, sobering, dropped in to leave our insignificant offerings of a sweetmeat or a crust, for Epona, as guardian of horses, was important to the Cornovii. Behind the temple, we found the horse-fair arena was empty, and for a while we kicked our bladder around that.

By now we were hot and sticky and close to the Sabrina.

“I’m going for a swim,” declared Amminus. “Coming?”

“Yes!”

“Yes!”

“Not me,” I said. “I want to think.”

The others, to whom thinking outside school hours on a summer’s day was a fool’s game, dashed down to the river, stripping as they ran. I had arranged with Bran for an early bath at home, and the sun told me there was still a good hour to spare. I sat on the brink of the low cliff that sloped down from just outside the rampart almost to the water’s edge. Below me lay the roofs of the row of warehouses, one of them stocked with my father’s pigs of lead and ingots of copper. In front of them was the long timber wharf. Moored to it today were only a couple of small and shallow-draught barges, one unloading olive oil and fish sauce all the way from Spain, the other stone-coal from the gorge a mere dozen miles downstream. The grimy porters heaving amphorae or sacks ashore would doubtless, when their work was done, join the bathers in the Sabrina.

The rest of the wharf was lined with naked male humanity, sitting, shouting, laughing, squealing, jumping off and climbing up: little boys minded by older brothers or slaves just as I had once been minded by Bran; in-between boys like my friends revelling in their freedom; almost-men boys studiously ignoring their juniors; grown men, young and middle-aged, taking a break from work to cool off or to wash. The water bobbed with swimmers’ heads and sparkled with their splashes. While the current was quite fast, at this time of year only toddlers would be out of their depth. Debris caught high in the bushes showed how winter floods could rise, but in winter only the hardy or the foolhardy bathed here.

To my right, on the pebbly beach just upstream of the wharf, some women were washing clothes, pounding them with stones as they sang a traditional song. From round the corner beyond came shrieks from the bathing place reserved for girls. They were segregated, in theory, but we used to spy on them. Of course we did. We were boys. Anyway, they spied on us. And here was our only source of information in that department, for paths could not cross at the public baths where it was female-only in the morning, male-only in the afternoon.

Downstream to my left, below the men’s pool, was the ford on the road to Cunetio and Bravonium. A loaded hay-wagon was creaking in from the country behind a plodding yoke of oxen. An empty mule cart was rattling out of town, followed by a horse-rider, probably a government official, officiously yelling at it to get out of his way. Below the ford two fisherman in coracles were spreading their net. Beyond them the river, bordered by smiling meadows, finally lost itself to sight behind a thicket on the bank. Above it the sharp twin peaks of Cordocum poked up remotely through the haze. Behind me, much closer, rose the ever-present lump of Virocodunum and its hill-fort. Between them stretched the long wooded ridge of Vindolocum. Midsummer rested green and luscious on the quiet hills. And our river was good. Our playground, our highway, our fishery and our laundry, our river was undoubtedly good. Thank you, Sabrina, I said to her. You are kind to us.

I was woken from my reverie by a new sound, as a squad of scruffy soldiers splashed across the ford, cursing raucously at having to wet their boots. Present-day Romans were not what they were. Aeneas would not have complained. This pampered lot was no doubt on its way from Bravonium to Deva and would stop off at the state hotel, of which they had free use at the civitas’ expense.

But it was time to get home. I made my way along the grass of the cliff-top. Ahead of me, after a couple of hundred paces, loomed a bush, and in front of it, nicely hidden from the girls’ bathing place but emphatically not from me, was a naked girl squatting wide-legged for a pee. She had not seen me. I stepped softly and was within a few paces, enjoying an excellent view, before she spotted me and straightened up, squawking and clutching at her breasts; which gave me a better view of what interested me yet more. I grinned to myself as she fled. She was Senovara, daughter of Lovernius the stonemason, with an attractive face, an attractive body, but a reputation of being more prim and proper than was good for her. The boys would be green with envy when I told them. They might even accuse me of making it up, which would be grossly unfair.

I turned in through the postern gate and cut across the town, nodding to my friend the policeman who was as usual bored, his only real job being to chuck drunks out of taverns. I wrinkled my nose at the putrid stink of the tanyard, savoured homelier stenches from the cattle market and backyard pigsties, half-closed my eyes to the acrid fumes of stone-coal from a bronzesmith’s hearth. Then I smelt the wood-smoke from our own little bath suite. Our household was modest and economical, and our bath was heated only when it was needed in the afternoon and early evening. Mamma’s was the first slot, followed by mine and then by Tad’s. Our slaves bathed as convenience allowed.

I found Bran in the dining room, on his knees and washing the mosaic floor with its simple design of stylised flowers surrounded by a wide border of meanders. I flopped down beside him and helped, and when the floor was done and the dirty water poured down the drain, we went to the bath. As Bran began to oil me, I got down to business with my first question.

“Bran, can I ask you something? About last night, when you didn’t want to join us at the table. Yet you’d been happy for me to wait on you at your meal. I know you’d already had wine, but even so … Why did you say no?”

He looked at me consideringly, as if debating whether I was old enough to understand.

“It’s complicated. You’re free, and you can do what you like. I’m a slave, and I can’t. That’s the usual rule. Even in this house … well, everyone knows what you expect us to do, and what you don’t expect us to do, and you respect our feelings. When your father said that if the Romans hadn’t brought wine to Britain you’d be drinking beer, he knew it wouldn’t offend me, because he knew that my family prefers wine. He might have said that if the Romans hadn’t brought the custom of lying on couches for meals you’d be sitting on benches or stools. But he didn’t, because he knew that we still prefer benches, like all the Irish do, and lots of Britons too. Saying that might have made me feel, um, uncivilised. So he didn’t say it.”

I nodded. I was following him perfectly. Bran had paused in his oiling to concentrate on what he was saying.

“In the same sort of way,” he went on, attacking my legs, “you’re considerate about giving us orders. Even in this house we can’t say no, if we’re ordered to do something. But we can say no if we’re asked in the right way, like ‘would you care to join us at table?’. And you’d never even ask us to do something we might think was unreasonable, let alone order us. The other way round, never can we order you to do anything, even in this house. And we have to be careful about what we ask. None of us would have dreamed of asking you to wait on us at table last night. But you offered to. You asked if you could, off your own bat. It wasn’t unreasonable. It was almost a joke. But not a real joke,” he added hastily, “because we could see you were serious. We didn’t play along with you just because you’re young, or because you’re my master.”

He had finished oiling me and was wiping his hands.

“And there’s another thing. If it had been my father who was invited to join you at the table, he might have said yes. But he’s the same age as your father. I’m not. I respect your father enormously, but I’m never as, well, as comfortable with him as I am with you. But I knew he wouldn’t be angry, or even disappointed. So I said no.”

“But if Tad hadn’t been there, and I’d asked you to join me, would you have said yes?”

“Yes. Almost certainly yes.”

“Ah!” Now for my second question. “Bran, something else. Who scrapes you in the bath?”

He was surprised. “Why, nobody. I have to scrape myself. My father respects my privacy. He’d never come in when I was bathing, any more than yours would when you were.”

“And you can’t scrape your own back.” I took the plunge. “Bran, would you like me to oil and scrape you? Now?”

His blue eyes gazed at me for what seemed an age. “Thank you, Docco,” he said softly, coming to a decision. “Yes, I’d like that.”

Without more ado, he unbuckled his belt, slipped off his tunic, untied the string of his drawers and stepped out of them, and lay down to be oiled. I was no stranger to nude male bodies. I spent countless summertime hours naked in the river with my friends, and we often oiled and scraped each other, occasionally at the public baths when our pocket money could run to it, more frequently in one domestic bath-house or another. But my friends were all much the same age as me, and we could not boast a single body hair between us. Nor were older bodies a total mystery. I had seen plenty in the river and at the baths, all the way from pubescent to geriatric. But never before, I reflected as I poured oil from the flask on to my hands, had I been at such close and intimate quarters with an older body.

For all that Bran was fourteen to my eleven, we had grown up together and I still thought of him as a boy rather than an incipient man. I constantly saw his torso and his legs, but it was many years since I had seen him totally naked. I had expected his equipment to be larger than mine, and so it was, considerably larger. But for some reason I had not expected him to have hair. Yet there it was, a bush of already some size, though fine rather than coarse. All this, as I oiled him, I carefully avoided, just as he avoided mine, and I did not allow my fingers to stray into his crack. At first he lay tensely as if he did not fully trust me, but soon he relaxed, and when he was done we clopped in our sandals to the hot room.

To show him that roles were being fully shared, I sloshed water on the scorching floor to raise steam, and we lay down together on the slab. He was very quiet, and I looked at him sideways. His eyes were shut and his hands behind his head. In his armpit were wispy hairs. I had noticed those before; and, now that I thought about it, his voice had been deepening over recent months, though so gradually that I had hardly noticed. I had simply failed to put two and two together about his emerging manhood.

“This is so strange,” he said out of the blue.

“But good?” I asked anxiously.

“Yes. Good. I never thought I’d be with a free man, a citizen, almost on an equal footing.”

“Well,” I laughed, “when you’re both starkers it’s difficult to be unequal, isn’t it?”

“Oh no. It’s easy, believe me. To be equal, there has to be the same freedom on both sides. The freedom to give. A free man has it. But a slave can’t give to a master, not freely, because he’s under an obligation. You know that some masters, um, exploit the fact that their slaves can’t say no? Take advantage of them? Impose themselves, especially when they’re both naked?”

He was putting it delicately, I realised, for my supposedly delicate ears. But I knew from hearsay what he meant. There were men, even Britons, even in Viroconium, who had that reputation. And I read his comment as a warning, if not for the present, at least for the future. Not that I needed the warning.

“Yes, I know. But Bran, don’t worry. I’d never dream of, er, taking advantage of you.” I meant it, with all my heart.

“No. You wouldn’t. I know that. Shall I scrape you?”

By now we were both sweating hard, and he went into his usual routine. When he had finished my back, “Roll over,” he said.

I twisted my head to grin up at him. “Who said a slave can’t give his master orders? You just ordered me to roll over!”

He responded by smacking me playfully on the backside. Never had he done such a thing before. I rolled over, wearing not only my grin but my normal erection. He was standing beside the slab and I could not see below his waist, but I sensed a sudden worry in him.

“I’m sorry,” he said, “but I’m in the same state as you. Would you rather I went?”

“Of course not!” I cried. “If you don’t mind me like this, why should I mind you? We’re equals like this, or as equal as we can be.”

“There are things that equals can do together, which unequals can’t. But yes, we’re as equal now as we can be, as long as I’m a slave.”

“Good. But Bran.” This was the cue for my third question. “You said yesterday you wouldn’t accept freedom just as a reward for good service. Does that mean you’d accept it for some other reason?”

“Yes,” he said slowly. “I might, if the circumstances were right. But that’s in the future, if it ever comes at all. I can’t see that far ahead. Let me do your front.”

An enigmatic and unsatisfying answer, but I could press no further. He did my front as usual, and then it was his turn. I slid off the slab, and as I was feeding my feet into my sandals he lay down on his belly. I had missed, for the moment, seeing what I was hoping to see. I took a great deal of care in scraping his back clean of sweat and oil and dirt — plenty of dirt from the stoke-hole — and I did not trespass. But there was fine down on his thighs, which intrigued me.

“Bran, does scraping take the hair off? Rather like shaving?”

“I don’t think so. There are plenty of hairy men around who must have been scraped for years.”

“That’s a pity. I don’t want to be hairy.”

“Maybe you won’t be. After all, your father’s not very hairy, is he?”

“That’s true. Right, back done. Roll over.”

Bran seemed to be summoning up courage, and hesitated. But he rolled over, and I drank in the sight. As with naked male bodies, I was no stranger to erections. My friends, like me, regularly sported our little ones in the bath, and we had even seen a few in the public baths where men often made assignations, and we had giggled at them. But, to me, an erection seen at close quarters on a handsome and maturing young man was a complete novelty, and a fascination. It did not, as such, turn me on, for I was too young for desire. But, like all my friends, I knew what erections are for. I knew all about what men get up to with men and with women. Like the rest of our community in those days, we talked about it without shame or inhibition. We did not yet have to guard our tongues. In my age-group it was no more than salaciously theoretical talk, for the practical and personal application lay in the future. None the less, even if I had no desire, I did have a boy’s full and boundless share of curiosity.

As I worked down Bran’s firm chest and belly, I could not keep my eyes off his proud display.

“I can’t wait to be like that,” I said, nodding at it as I meticulously bypassed it with the strigil. “But there’s still three years to go.”

“It may be more for you, Docco. I think I’ve, um, bloomed earlier than most.”

That prompted me to risk a new and unplanned question which had been in my mind ever since he stepped out of his drawers. With my other friends I would have had no qualms, but Bran was different. His personal territory was different. So I asked it with some trepidation, and phrased it carefully.

“Bran, can you make seed yet?” I knew about seed, but it was another theoretical knowledge.

“Yes. These last six months or so.” He hesitated again. “And I’ve used it, too.”

“What do you mean?”

“That I’ve, well, put it in other people.”

My first reaction was further shock that my companion, my friend whom I still thought of as a boy, had already become a man without my knowing. My next and ignoble reaction was jealousy. He was my Bran, wasn’t he, my slave, not other people’s. But worthier thoughts at once took over. In this realm he was his own master, or he should be, and I was glad for him. Envious, too, that he was so far ahead of me on the path to manhood.

“Well done! With a girl, or a boy?”

“Both. One of each.”

There were plenty of slave boys and girls in Viroconium, and I could not possibly ask who. That was too personal, with Bran. But other questions might be permissible.

“But Bran … girls … babies?”

“It’s all right if it’s during their safe period. Don’t you know about that?”

I did, theoretically again. “Oh yes, I was forgetting … But Bran, what’s it like? I mean, being in a girl or a boy?”

He screwed up his nose. “You’re too young to understand. I’m not trying to be superior, or off-putting, but you can’t. Not until you begin to bloom. It’s, well, it’s the same sort of thing as doing it by yourself, but better. Much better. And you can’t really understand even that yet, can you? I wish you were older.”

“So do I.”

He thought a bit more.

“Oh, I can’t really describe it, Docco. It’s ecstasy. That’s the nearest I can get.”

There, as I scraped his legs and tried to visualise ecstasy, the conversation languished. But when I had finished and everything seemed to be over, he suddenly said, “Docco. Would you like to see?”

“See what?”

“See me make seed, by myself. It might give you some idea of what it’s like.”

I looked at him in astonishment. Of desire, as I said, I had nothing. But of curiosity I had plenty, and now of gratitude, and even of humility.

“I’d never have asked you to do that.”

“I know you wouldn’t. That’s why I’m offering. Like you offered to wait on us last night. Like you offered to scrape me.”

Was he really right that a slave can not give freely? Or was he offering in repayment for my offers? I was not sure, but it touched me deeply.

“Well, if you really don’t mind, yes please.”

“But you won’t tell anyone, will you?”

“I won’t, I swear. Not a soul.”

He smiled at me, grasped himself between fingers and thumb, and began to manipulate his foreskin up and down, faster and faster. His round tip emerged and disappeared, emerged and disappeared. His left hand fondled his balls. The technique was familiar. Ayear ago I had learned it from my friends. But, while it was undeniably pleasant, with me it generated nothing approaching ecstasy, still less any visible product. What fascinated me now was that it was sending Bran into another world. He closed his eyes, he bared his teeth, he groaned, he panted. After a while, a little clear fluid began to ooze out.

“Hold my hand!” he gasped.

I held his left hand. He worked away ever faster, his grip tightening, and suddenly he arched his back with a great cry from his depths. Out shot a squirt of white liquid which splashed on his neck. Five more, ever smaller, landed in drops on his chest and belly. The pressure of his hand nearly broke the bones in mine. As I watched spellbound, he sank back sweating, panting still, and his erection slowly subsided. I had an inkling at last of what lay in store for me.

Looking back over the years, I can now see that Bran had after all answered my third question, the unresolved one. He would accept his freedom if it were offered in love. All the signs were there. But, may the gods forgive me, I was too young to read them. Yet, having an inkling at last of what love might mean, I leant down and kissed him gently on the lips.

“Thank you, Bran,” I said.

He raised himself on his elbows and kissed me back. “Thank you, Docco.”

That moved me more than all that had gone before. As I lowered my face to hide the tears, my eyes lit on his body again. Down through the smooth meadows of his chest and belly a river was trickling, to lose itself in the thicket below.

Chapter 3. Vergil (360)

Libidinis in pueros pronioris, quorum maxime dilexit Cebetem et Alexandrum, quem secunda Bucolicorum ecloga Alexim appellat, donatum sibi ab Asinio Pollione, utrumque non ineruditum, Cebetem vero et poetam.

Vergil had a marked desire for boys. Above all he loved Cebes and Alexander. The latter, whom in the second Eclogue he calls Alexis, was a gift to him from Asinius Pollio. Both boys had some education; indeed Cebes was a poet as well.

Donatus, Life of Vergil

I was quiet at dinner. So was Mamma, who was better but pale. So too was Bran, who was waiting on us again; but then he never spoke at meals unless he was addressed. But Tad, who arrived a little late, was in expansive mood. He had a present for me, he said. It would have to wait until after we had eaten, but if I wasn’t bowled over when I saw it, then he was emperor of Rome. Although everyone likes getting presents, I could imagine nothing that would even approach Bran’s gift to me that day, and over Tad’s I was pessimistic. It was probably some trinket that had caught his eye, or a new knife, or a bargain tunic which would split at the first wearing and Roveta would have to mend. But I played the game, and Mamma joined in, of making wild and silly guesses. Apedigree stallion. An ostrich. A luscious concubine. A chest of treasure buried by the Fair People which Tad had found at the rainbow’s end.

When we had finished with our snails and fruit, Bran cleared the dishes. Tad went out, and came back with a cloth-wrapped bundle which he laid on the table. Bran would normally have left at this point, but he stayed on, hovering in the background. I saw lively curiosity on his face and smiled at him.

“Open it up, then,” Tad ordered.

I unwrapped the cloth. Inside was a stack of narrow double cylinders of parchment, each about a foot and a half long and with wooden knobs at both ends. They were tied together with twine. I fumbled with the knot.

“A knife, please, Bran,” said Tad.

I cut the twine and the cylinders clattered apart. Each carried a little projecting label, and Tad bent over to peer at them. “Try that one first,” he said, pointing.

I picked it up and unrolled it. After a few inches the parchment gave way to a pale brown sheet, coarse and grainy, of a material I had not seen before. I fingered it.

“Papyrus,” said Tad. “All the way from Egypt.”

I unrolled more, and there was writing, column after column in regular and beautiful capital letters. Amazed, I read the beginning out loud. I have since acquired the difficult knack of reading to myself, but I did not have it then. Almost everybody read out loud, even mundane things like sums or accounts.

The title, written in red at the head of the first column, said,

VERGILI MARONIS AENEIDOS INCIPIT LIBER PRIMVS

HERE BEGINS BOOK I OF THE AENEID OF VERGILIUS MARO.

It continued, in black, Arma virumque cano …

I looked up, flabbergasted. “Tad!”

He was beaming at me. “I bought them off Lugubelinus. For a song.”

“But … they’re not ordinary books, with pages.”

“No. They’re scrolls. They’re old … must be a hundred years old at least. From the time before proper books came in. Haven’t you heard of them?”

No, I hadn’t. All I knew was proper books, and they were uncommon enough. There were none in our house. At school, all we had ever had was little booklets of a dozen parchment pages stitched together, full of grammatical rules. Nobody I knew possessed a real book, except old Nonius. When he introduced us to Vergil he had read from his own, a proper thick book bound with boards. None of us expected, or was expected, to have his own copy, let alone ancient scrolls.

“Oh, thank you, Tad! It’s unbelievable! And is it all here? All of Vergil?”

“Not quite all, I’m afraid. There’s one scroll missing.” He peered at the labels again, muttering. “Yes. There are two books of the Aeneid to a scroll, and the one with Books XI and XII is missing. Sorry about that. It must have been lost a long time ago, because Lugubelinus said he’d never had it. So these five” — he sorted them out — “have most of the Aeneid, and these two have the Eclogues and Georgics.”

“Oh, Tad!”

I was desperate now to get away and pore over my scrolls in private, but first I must thank him properly. I gave him the biggest hug I could. My head did not come up even to his chin, but I was on top of the world. My friends would be … no, they wouldn’t. They would be green with envy at my close-up view of Senovara’s pussy, but not at my nearly-complete Vergil. They were not that sort. And then my eye lit on Bran. He was still in the background, but almost twanging with interest and hope.

“Thank you, Tad,” I repeated. “I’m going to take them to my room and start reading them. Bran, would you like to come too?”

Mamma smiled at us. “But don’t be too late to bed! You both need your beauty sleep.”

We were late to bed. Very late indeed. The evening was sultry and we stripped off our tunics. We unrolled the first scroll on the floor and lay on the rug in front of it, side by side, propped on our elbows. I let Bran start. Arma virumque cano … he intoned, almost as well as old Nonius. He carried on for thirty lines or so, down to Tantae molis erat Romanam condere gentem, Such was the heavy cost of establishing the Roman people.

There he ended, and looked at me wide-eyed.

“Oh, gods!” he breathed, and I knew that he was as enslaved as me.

So we continued, reading in turn. From time to time we paused to debate what Vergil was saying, and once to wonder what kind of a man he was. When daylight faded, Bran went to find a lamp and we closed the shutters to keep out the moths. Drunk on words, we carried on reading …

I was woken by the insistent demand of my bladder. The simple need to empty it turned into simple farce. The lamp had run out of oil and it was pitch dark. I was still lying on my front, the floor was hard as iron and, although Bran’s arm seemed to be over me, I was cold. I disentangled myself gently and crawled blindly around the room in search of the pisspot. Once I had found it, I had a long struggle trying, by touch alone, to untie the string of my drawers. Only then could I let rip, trusting that I was aiming straight. Yes, I was, and the noise of it roused Bran. He came over, in urgent need of the pisspot too. He had a similar struggle with his drawers, and by the time our joint fumblings had succeeded and I had pulled them down for him I was giggling uncontrollably and he was almost paralytic with laughter.

“Oh gods!” he gasped. “I’m going to burst! Where’s the damned pot?”

“Here,” I managed. “Stay put.”

He was on hands and knees, and I moved the pot into what I hoped was the right position. I had promised not to take advantage of him, but this didn’t count, did it? No,this wasn’t taking advantage, it was just play. I felt for his penis, grasped it, and aimed.

“Shoot!”

As he shot, groaning with relief, I pulled and squeezed it like a cow’s teat, exactly as if I were milking at the farm. Psss — psss — psss went the spurts into the pot. That sent him into even more helpless spasms which threatened the floor, so I put my other hand on his buttocks to hold him still. At that point, having lost all control, he farted, and I felt the warmth of it on my hand. When the sound of pissing died away, I gave him another squeeze and felt him swelling between my fingers. That set me swelling too, and I let go. I knew, obscurely, that from this point it would be taking advantage.

“Bed!” I spluttered. “I’m freezing.”

I had to help him into bed, such were his convulsions, and we snuggled together under the blanket. Without thinking I put my arms round him, his came round me, and we lay tight, erection against erection, as our quaking worked itself out. And so we fell asleep again.

I was usually woken by the sun, but not that morning. Nor was Bran. We were woken by a knock on the door and by Tigernac poking his head in. He seemed relieved to find Bran, but surprised to see us so intimately close, and even concerned when he spotted the two pairs of drawers on the floor. He said nothing and went out, but Bran, rubbing sleep from his eyes, sat up in alarm.

“Oh dear,” he said. “I’m going to get a wigging. I’m sorry.”

“Well, I’m not. Not a bit sorry for anything. For yesterday in the bath. For last night with Vergil. For sleeping together. For that fun with the pisspot” — he grinned at that — “Thank you, Bran.” And I kissed him again.

He kissed me lightly back. “And thank you, Docco. For all of those. But I’m supposed to get you up and ready, and help get breakfast.” He was out of bed, slipping on his drawers and tunic. “I must run. You’ll find a clean tunic and drawers in the chest. All right?”

“All right. And Bran! Borrow the Vergil whenever you want.”

He smiled and went out, and my heart sang. Over the past day I had acquired not only an old Vergil but a new Bran, an even better Bran, a deeper friend, more trusting and caring, more fun, more equal.

I dressed rapidly, carefully rolled up the scroll and put it away with the others, and ran to the spout to splash my face. I made it to breakfast just as Tad was finishing his. Tigernac was there, looking worried.

“So Vergil kept you both up, did he?” asked Tad, half stern, half humorous.

“Yes, Tad, till I don’t know when. Sorry. We fell asleep over him, and when we woke up it was cold and we had no light. So Bran slept with me.”

Tad looked at me quizzically. “That phrase can mean more than one thing, Docco. You know that, don’t you? One can be quite blameless. The other … well, it’s blameless too, I suppose, but you’re very young for that sort of thing. And there’s another consideration.” His eyes flickered towards Tigernac.

I understood him. My theoretical knowledge, as I have said, was considerable. But in practice I was an innocent. I was only eleven, remember.

“It’s all right, Tad,” I protested. “We didn’t do anything together. Except sleep. We didn’t even think of doing anything.”

“Good. I believe you. That’s all right then. But don’t make a habit of it. All right, Tigernac?”

Tigernac nodded back, visibly reassured. No doubt he would ask Bran the same question, and he would get the same answer.

“I must be off,” said Tad, “but I’ll be back for lunch. Have a good morning at school, if you can stay awake.”

As I finished my bread and cheese, I reflected. I was a truthful child, as a rule. Mamma and Tad had drilled it into me, and life was easier that way. But was it true that Bran and I hadn’t done anything together? What about me milking his cock? No, that still seemed different. That was a bit of boyish fun, not the sort of thing Tad had in mind. And I’d said we hadn’t even thought of doing anything. Well, I hadn’t. Not that sort of thing. But had Bran? Remembering yesterday’s revelation, I was hit by a sudden qualm and scurried to my room. Bran had already dealt with the brimming pisspot, but the bed was still unmade. I looked at the sheet and blanket. No wetness, no staining. Everything was all right. I was dimly aware that Bran might have exercised considerable restraint.

Next, to Mamma, who was still in bed. I kissed her, said good morning, asked how she was, and apologised for being in a hurry as I had overslept.

“But you can’t go to school like that, Docco,” she complained. “Your hair’s a haystack.” Bran normally combed it for me. “Use my mirror.”

It was a wonderful thing, an heirloom of solid silver and worth, I’m sure, a great deal of money. The disc was a foot across, and the complex handle on the back was formed by two thick bands of silver looped together in a reef knot. Around the edge ran a gilded wreath of flowers. The polished face was slightly convex, so that even if you held it at arm’s length your head was larger than the disc. Besides, it was very heavy. I propped it on Mamma’s dressing table and stood back to reduce my curly black mop to order with one of her combs.

“That’s better!” she said, inspecting me. “You’re a very handsome lad, did you know? And I love you.”

“And I love you, Mamma. See you at lunch!”

At last, to school. Although it was only a hundred paces down the street, I was almost late, and as I sat down old Nonius was opening his Aeneid. Old Nonius? He can hardly have been over thirty, but already I thought of him as old because already I worshipped him. On our first day he had read as far as the point where the Trojans land on the shores of Carthage after the storm. He now carried on from where he had left off. I sat, chin on hands, drinking it in, matching it with what we had read last night. Then suddenly, after only fifteen lines or so, something jarred. Dederatque abeuntibus heros, he had said. That was not what Bran had read from my scroll. Startled out of my absorption, I jerked upright. Nonius happened to be looking in my direction, and stopped.

“Something surprises you, Docco?”

I felt small and confused. “I’m sorry, sir. It’s just that the words I know are different.”

“You know the whole of the Aeneid by heart, then?” He was being only mildly sarcastic.

“No sir. But we were reading it last night, and my copy says dederatque abeuntibus hospes. But it doesn’t matter.”

“But it does matter. We need to get the master’s words right. Is your father’s Aeneid complete, then? Like this?” He patted his own book.

“Not my father’s, sir. Mine. And it’s missing Books XI and XII. And it’s not a proper book. It’s on scrolls.”

Nonius’ eyebrows went up. “It will be old, then. No copy is ever perfect but, other things being equal, older copies are likely to be less imperfect than newer ones. There is less opportunity for errors to creep in. I would like to see yours, Docco, if I may. Would you have a word with me, please, after school?”

I wished I had not raised the matter. Whether it was heros or hospes, the sense was virtually the same. When Nonius had finished his stint with the Aeneid he handed us over to an assistant who introduced us to Sallust which was, by comparison, boring. Then we were finally freed, and Nonius sought me out.

“You have a good ear, young man, to spot that discrepancy. And enthusiasm too, to be reading Vergil out of school. With whom were you reading it?”

“With my slave, sir. Bran. He’s older than me. Fourteen.”

“Bran? So he’s Irish?”

“Only by descent, several generations back.”

“And what education has he had?”

“Elementary, sir. My father paid for it.”

“And was he reading Vergil with you at your command, or of his own free will?”

“Oh, of his own free will.” I was quite shocked that Nonius might have thought otherwise. “He’s as interested as me.”

“Hmmm. Docco, may I ask you to introduce me not only to your scrolls, but also to Bran?”

“Yes sir, of course. Shall I bring them here, or will you come to see them?”

To cut a long story short, he came to our house. He inspected the scrolls with interest, dipping into them at random, reading to himself, nodding here and pursing his lips there. He asked to borrow them one by one, starting with the second so as not to interrupt our reading, in order to compare their text with his own book. He talked to Bran, had him read and explain a passage, and was impressed. It was lunch time and Tad invited him to join our simple meal. Over the eggs and vegetables and wine Nonius remarked that talent and enthusiasm should be fostered, and asked Tad if he would allow Bran to join his school for a year or two, free of charge. Gladly, replied Tad, having consulted Mamma with his eyes, provided of course that Bran and his parents agreed. Bran, who was waiting on us, gave an eager yes. Tigernac and Roveta, when summoned, gave a more qualified one, asking for the household routine to be reviewed to compensate for Bran’s absence.

If Nonius was surprised by this democratic consultation, he did not show it. And as he was leaving with the scroll, I ventured to ask him a question.

“Sir, we were wondering last night what sort of man Vergil was. Please, can you tell us?”

“Better than me telling you myself,” he said, “I have a book which will tell you. Anew book, which arrived from Rome only a month ago. If you will treat it carefully, I will lend it to you in return for the loan of this scroll. You may collect it now, if you will come back with me.”

And so we brought home Donatus’ Life of Vergil and read it there and then. It was short and terse, but informative. When we reached the section on Vergil’s love life, Bran snorted.

“Typical Roman, having it off with his slave boys who couldn’t say no. What does the second Eclogue say about this Alexis? Let’s have a look.”

We found the right scroll. The poem began:

Formosum pastor Corydon ardebat Alexim,

Delicias domini, nec, quid speraret, habebat:

Tantum inter densas, umbrosa cacumina, fagos

Adsidue veniebat: ibi haec incondita solus

Montibus et silvis studio iactabat inani:

‘O crudelis Alexis, nihil mea carmina curas?

Ni nostri miserere? Mori me denique coges.’

The shepherd Corydon had lost his heart to the beautiful Alexis. But Alexis was his master’s favourite, and Corydon’s hopes were unfulfilled. His only comfort was to haunt the spots where the tall beeches spread unbroken shade, and there, alone in his unrequited love, he raved to the hills and woodlands these disordered words: ‘Cruel Alexis, do you care nothing for my songs? Have you no pity for me? You will end by driving me to death.’

“I like the language,” I remarked, “but Corydon sounds a bit soppy.” I was too young to recognise the pangs of love.

“Not soppy to me,” was Bran’s verdict. “I know exactly how he felt. I’m a slave too.”

Did he mean that his own love was his master’s favourite? No telling.

“Anyway,” I said, looking at the sun, “it’s time we had our bath.” Our bath it had already become, not my bath.

Thus Bran became a schoolboy again, and together we worshipped at Vergil’s shrine.

Chapter 4. History (360-2)

Planis absolutisque decretis aperire templa arisque hostia admovere, et restituere deorum statuit cultum. Utque dispositorum roboraret effectum, dissidentes Christianorum antistites cum plebe discissa in palatium intromissos, monebat civilius ut, discordiis consopitis, quisque nullo vetante religioni suae serviret intrepidus … nullas infestas hominibus bestias ut sunt sibi ferales plerique Christianorum expertus.

With simple and unambiguous decrees Julian ordered that temples be opened, sacrifices brought to the altars, and the worship of the gods restored. To increase the effect, he summoned to the palace the squabbling Christian bishops and their bickering flocks and politely warned them to lay aside their differences and allow everyone to practise their own belief boldly and without opposition … He knew from experience that no wild beasts are as dangerous to man as Christians are to one another.

Ammianus Marcellinus, Histories

The summer wound towards its close, and I turned twelve. I was spending most of my time, these days, with Bran. I had more in common with him now than with my other friends. They had no problem with a slave, especially so congenial a slave, as their fellow-pupil. But where we were deeply bewitched by Vergil’s magic, they were not, and they saw us as swots and teacher’s pets. Which was no doubt true. We had finished reading the Aeneid by ourselves — having spent weeks in after-school hours laboriously copying Books XI and XII from Nonius’ great tome — and were well into the Eclogues. Already we had large chunks of both by heart. Why were a typical British youngster and a not-so-typical Irish youngster so enslaved by a Roman poet? I can give no good answer, but the fact remained. And, as time went by, it put us in touch with unexpected people.

One afternoon that September, for example, Roveta sent Bran to the market to buy mushrooms. As so often nowadays I went with him, and as we walked we were comparing Vergil to our own native tales.

“The Aeneid’s more, um, well, sort of elaborate, isn’t it?” I remarked, struggling for words.

“More literary, you mean? With more craft in the language? Yes. The Irish tales … about ConCulainn and Fergus and Brid and suchlike … they’re much simpler. Great stories, but not so much skill behind them. I suppose it’s partly because Vergil’s in verse, not prose. And partly because all Latin literature’s written down from the word go. It’s meant to be read. The Irish tales aren’t written down. They can only be memorised and spoken. I think that’s the difference.”

“Yes, and the same with the British tales … about Lugus, and Rigantona, and Vedicondus, and Maponus son of Matrona. Though some of them are in verse. But they’ve never been written down either. Wouldn’t it be strange to see British in writing? Or Irish.”

“I wouldn’t know how to set about writing British, or Irish. How to spell it.”

We both laughed. It was unthinkable. Latin was the only language that was written. Oh, and Greek — in the cemetery we had puzzled over the incomprehensible gravestone of some immigrant Greek.

We were now abreast of the tavern next to the Town Hall. It was mild and sunny, and several customers were sitting outside, drinking and talking. Among them were two ancient army veterans, well-known local characters who suffered, it was said, from verbal diarrhoea and would, if given the chance, bore you to tears. I had never spoken to them, or they to me. To my young eyes, if truth be told, they were scary: wrinkled, deeply sunburned, bald as eggs but with stubbly white beards, and of incalculable age. While Pacatus had at least one tooth, Titianus apparently had none.

As we passed by, we overheard a snippet of their talk.

“One of them,” Titianus was saying, “says R.S.R. I can do that. It stands for Redeunt Saturnia Regna. The golden age returns, or something like.”

That stopped us in our tracks.

“And the other one,” he went on, “has the next line, doesn’t it? But I’m blowed if I remember how it goes.”

“No more do I,” said Pacatus, scratching his stubble. “Except that it’s Vergil. You’ll have to dig it out and look.”

Bran and I exchanged a glance, and he nudged me. Emboldened, I piped up.