Leaving Flat Iron Creek

CHAPTER SEVEN

The train pulled into Stockton, California, on the third day of my cross-country odyssey. I stepped off the train into the blistering noonday heat of central California. I asked the station manager about the circus, and he told me they left town. Unable to find a billing announcement, I asked a livery man who was loading freight onto a freshly painted wagon. Two Shire colts stood perfectly still as he worked. He ignored me and seemed wrapped up in his work.

“Yeah, what’a’ya want?” he finally spat.

His jet black, short-cropped hair his square head accentuated his serious, angry look. His torso filled his wore, tight shirt causing buttons and sleeves to bulge when he lifted the boxes and barrels onto his livery wagon. I guessed him to be five-six, but he appeared taller because he wore heavy railroad boots.

I felt heat surge throughout my body. A cold sweat swept over me from head to foot. I had minor anxiety when I got on the train in Ft. Wayne but nothing like this. My leg muscles softened and my knees turned to rubber. His harsh voice brought back bad memories. I took one step away from him. “What’cha want?” he yelled.

I couldn’t make my lips work. That was all I remembered until I found myself propped against the edge of the freight dock. The man I had spoken to stood over me, splashing water in my face. A few men talked to him. I was outside my body watching them talk about me. “Maybe it was the heat. Is he drunk? Should we call the police?”

I tried to shake my head but it wouldn’t move.

“He’ll come round,” the livery man said. “Give him a couple of minutes. Looks like he had a hard time of it with his leg and all.”

I tried to move my leg, but it did not respond. The livery man just looked down at me with piercing brown eyes. His hands rested on his hips, making his biceps bulge. Then he bent over and put his hand on my forehead like my mother did when I had a fever.

“You OK, man?” he said in a caring tone.

“Yep, I think,” my lips struggled to form.

He childishly apologized, “What wuz you askin’ me?”

“I was inquiring about the Rawlings Bros. Circus.”

He looked puzzled.

“I work for the circus and have been recuperating from an accident.”

“What kinda’ accident?”

“It wasn’t really an accident,” I said. “I was pushed off a moving train.”

“Is that true?” he asked with naive curiosity in his voice.

I looked into his eyes, which were deeply set in his deep olive face.

“Very true.”

“Why are you looking for the circus now?”

I thought I was going to pass out again, and he detected the stress that his question caused. “I should know better than to ask too many questions,” he said softly.

He rose and then took one step before realizing I was still on the ground.

“Can I buy you lunch?” I said, trying to smooth over the awkward situation.

“Only if you can git off yar ass,” he said as he walked behind me, placed his huge hands under my armpits, and hoisted me up. His hulking shoulders hardly flinched as he lifted me to my feet.

I dusted off the seat of my pants and steadied myself.

“Man you don’t look so good. Take it slow.”

Fortunately, a lunch counter stood across the street in one of several similar white clapboard buildings. The diner had double front doors and a plank sign with “Railroad Diner” in faded blue letters that hung lifeless in the hot, dusty afternoon air. My new friend followed me as I opened the right screen door and stepped across the threshold. I motioned for him to come inside, but he just stood in the doorway. “What’s wrong?” I asked with irritation.

I knew I had to sit soon. The lunch counter, with a stool bolted to the floor every three feet, stretched down the left side of the room. About half of the stools were covered by the blue demin, gingham or calico of a patron’s clothing. A tiny, wiry woman with wispy white hair scurried back and forth behind the counter placing white stoneware plates covered with meatloaf, potatoes and gravy in front of customers. The temperature in the room had to have been ninety degrees. Breathing was a chore. The sounds in the room were muffled, but the longer we stood in the doorway the louder the murmurs became.

“Shut the screen, goddamnit. You’re lettin’ in the flies,” someone snapped.

“Bert,” the woman said angrily, “watch your mouth!”

I finally pulled my friend by the sleeve through the door. I moved to one of the three square wooden tables nearby and sat down quickly. My friend looked from one side of the room to the other. I sat down and slouched in my chair, hoping the eyes would turn away. He followed my lead, but the chair he chose slipped out of his grasp and clattered to the floor. All eyes turned back on us. My friend almost bolted out of the door.

“Meatloaf looks good,” I reassured him, “Do you want some? That’s what I want.”

He pulled his chair up to the table. His grimy hands needed to be washed. He looked at them.

“I’ve got to wash,” he said, making his way out of the diner.

I wondered if he would return. I quietly waited, noticing the overhead fans, doing little to drive out the heat. A few minutes later, the waitress startled me by loudly slipping the plate of meatloaf and mashed potatoes in front of me. She had a plate for my friend as well.

“I hope he comes back,” I said with less than full assurance in my voice.

“George’ll be here,” she assured me.

“What would you like to drink?”

“Water will be fine. Same for my friend,” I said.

“No, George likes milk,” she said as she turned and walked toward the kitchen.

Just as she predicted, George returned and drank the milk sitting before his place.

“How’d you know I wanted milk?”

I ate slowly without saying anything.

When my plate was clean, the woman brought us each a piece of peach pie.

'While ago you wanted to know about the circus,” Geroge said. “Well, they pulled out last night after midnight. I watched ’em.”

“Which way were they headed?”

He responded with the certainty of a fourth grader who knew the answer to a geography question.

“Modesto.”

I said out loud, “They’re performing now!”

“Wha’d’a mean?” he sputtered with a mouth full of pie.

“I mean the afternoon performance is about to start. When’s the next train to Modesto?” Without hesitating, George pointed out the window.

“That ones ready to go out there.”

“I mean the next one that I could catch,” I said with annoyance in my voice.

“Tomorrow, unless you catch the 610 at midnight,” he answered.

“OK, George, where do you think they might go after Modesto?”

He didn’t respond. I watched the waitress walk by our table and slow down so she could hear what was being said.

“I don’t know,” George finally said.

Although I was getting tired of asking questions, I found myself strangely drawn to George. “Let’s pay and go.”

I picked up the check and pushed my chair away from the cluttered table. The total bill was thirty cents. I took a silver dollar out of my pocket and put it in the hand of the waitress standing by our table.

“Young man,” she said, startling me, “if George goes with you take care of him. He’s special.”

Since the diner was virtually empty except for us, she sat down and introduced herself as George’s mother. She began to tell me about George as he sheepishly gazed at the floor.

He, like me, had a scar over one eye. George’s mother said he sustained the injury in one of the numerous fist fights he had when he was younger. George, I learned, was the product of a brief affair between a railroad construction worker and his mother one summer. She discovered that the man had wife in San Francisco and sent him packing. George was born in Stockton. She was thirty years old at the time and raised her son on the wages of a waitress.

George shifted nervously in his chair as she told the story. She unapologetically said, “As a boy George was constantly taunted because of his birth status. I told him he was a good person but George grew up defending his reputation with his fists.” As the story progressed, she told how he was befriended by an old priest who at one time had been an amateur boxer. The priest operated a little gym and taught George the fundamentals of boxing. “George worked very hard, but his height kept him from becoming a professional. He learned how to physically defend himself from the hecklers and loved working out with barbells. That’s why he has a barrel chest.”

She continued to tell me more than I ever cared to know about George, but she wouldn’t stop. She told me that George had odd jobs from a very young age and always gave the money to her. I could tell from George’s reaction that he was embarrassed about what his mother was saying but politely remained quiet. “I worry about his lack of confidence He would rather fight than talk.” She told me that they had lived in a small rented house on an alley near the railroad station restaurant, but about the time George was fifteen their house burned to the ground along with several other buildings. She said, “We moved into a rooming house but shortly George wanted his own place. It is room at the top of the stairs over a wholesale plumbing business not too far from the livery barn. He started cleaning stalls when he turned thirteen. He has lived in the same room for twelve years.”

I had heard enough and moved to leave.

“Do you want to see my room?” George asked. “You look tired and you could rest there before you move on.”

I accepted his invitation so we could get away from his mother. It occurred to me that his mother might be turning George over to me.

“If George goes with you, take care of him,” she said.

“It’s all I can do to take care of myself.”

She smiled and moved to the counter.

We left his mother in the diner. We said nothing to one another as we walked toward the wagon. George returned the rig to the livery barn about six. His boss, a man with a black cigar clamped in the right corner of his mouth, raised his black hat off of his forehead with his right hand. He pushed his greasy black hair back with his massive left hand. His hands seemed completely out of proportion to the rest of his short, stocky frame. He was the blacksmith and spoke with clinched words.

“George, why you so late?”

“Lota’ freight, Mr. Aston,” George said defiantly.

“Put the horses away but leave the wagon here. Then pick up freight from the 610 train. Can you get it?”

“Mr. Aston, I will see it gets done. Don’t worry, it’ll be right here on the wagon in the morning.”

“Give me the delivery sheets and git going.”

We both got off the box and George drove two horses into the barn. Aston never spoke directly to me or acknowledged my presence. I followed George around like a puppy. He seemed to care about how I was doing and asked frequently about how I was feeling. After he had fed and watered the horses, he turned to me.

“Seth, let’s go to my place so you can rest.”

I grabbed my bag off the livery wagon and fell in step behind him. The western sun hit George, casting a long full shadow. I followed about six feet behind. My leg was sore, and I limped noticeably. He turned the corner into an alley and started toward the outside stairs of a white clapboard house fifty feet away. He slowed to wait for me and then took the stairs that squealed or squawked under our feet. He grabbed the screen door handle and waited at the top as I slowly made my way up each stair.

He opened his room door and invited me in. The room was so tidy, as if a maid had been there to clean it. The towel by the sink was folded, and a lace doily covered the table top beside his bed. Lace curtains framed the window.

“Seth, sit down you look tired,” George said. “You want a bath? That’s what I do on Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday when I come home. It costs a dime for the bath and a nickel for the towel, but it’s worth it.”

“Yeah,” I said wearily. “Where?”

“Across the alley, I’ll show you. Leave your money and valuables here. Things disappear there. It’s never happened to me, but I’ve heard…”

His words trailed off as he headed toward the door. Except for a quarter to pay for the shower, I left my money in a bag on George’s floor. We traipsed down the stairs and across the alley, climbed up the porch, and opened one side of the double screen doors. The little reception area was dark and hot. No one was around. George walked up to the small counter and gently laid his big hand on the peak of a beautifully engraved brass bell. The tone resonated throughout the room. No one responded, and George rang once more.

My eyes wandered around the austere space. A rug covered the floor in the center of the room. A large oak pedestal table sat beneath a gas lit chandelier. Four elaborately carved oak chairs surrounded the table almost like those around our table at home. My eyes paused on the metal sculpture of a naked goddess centered on the white doily. From the figurine, my gaze led me to yellowed photos of women in fancy underwear that hung on the wall. The place was made sense. A woman, maybe forty years old, stepped from behind a curtain of clicking glass beads. “George, you here for your bath. Whose your friend?”

“Maggie, this is Seth,” he said. “Seth this is Maggie. We both want a bath.”

I nodded my head politely in Maggie’s direction.

Fixing her beautiful brown eyes on me, Maggie said, “Nothing else? Can I interest this young man in some companionship?”

“No, Maggie,” George said firmly, “just two baths and two towels.”

“Towels are clean. The water is fresh, but there isn’t much privacy right now. I had the curtains washed, and they’re still out on the line,” she explained.

“I don’t care, George if you don’t.”

The thought of a bath was appealing.

“Pay first, house rules,” Maggie ordered.

I handed her a quarter, paying for both of us. We went inside, which was almost like going outside. There were two big windows on our left and one similar window in front of us. Wires, strung from opposite walls, crossed in the middle of the room. Other wires hung from the ceiling, suggesting that curtains usually separated the room into quadrant spaces. Each quadrant had a tub, rather a watering tank of galvanized metal in the middle of the space. Beside each tub was a small wash stand and chair. Pegs on the wall were for clothes.

I stepped toward the tub near the screen door to see where Maggie had gone. She stood in a tiny backyard that was surrounded by a high stockade fence. As she bent down and picked up a bucket, water sloshed out as she strained to lift it onto the porch. I opened the door for her. She looked at me with saucer-sized, chocolate brown eyes

“Git undressed. This water’s good and warm, almost hot.”

I dutifully stepped over to the closest chair and sat down to pull off my boots. I stood up to unbutton my shirt exposing my chest. She looked intently my way.

“Can’t a man get a little privacy here?” I said sarcastically.

“Hun, you ain’t got nothing I haven’t seen hundreds of times. Git in.”

I stripped and stepped onto a wooden crate to get into the water. I faltered because of my leg, and George rushed over to steady me. I sat on a submerged stool as Maggie slowly released the pail’s contents over my shoulders. The warm water was soothing.

“Maggie,” George said while fully dressed, “you have to leave.”

“OK, George, you get your own water. Twenty minutes, and you’re out of here.” Maggie stalked out of the room.

He stood awkwardly unsure what to do. He fumbled with his belt and slowly let his pants drop. He sat down to untie his boots. Finally, he slipped out of his underwear to reveal a solid, large enlarged dick. I couldn’t help but look his direction. He smiled as he lifted the water bucket and poured it into the tank.

I smiled at child-like George and commented, “George, a stiff dick she has seen many times.”

“But not mine. Seeing your tan butt made it get hard.”

I took a deep breath, “So it’s me not her that turned you on.” I laughed softly.

Continuing in his soft, serious tone George, “I don’t know what happens but sometimes I just get hard like this and it stays that way until I do something about it.”

“That part I understand. Are you going to do something about it here?

He looked at me puzzled, “That would get the water messy. I don’t think I should.”

My tone changed and I suggested that he sit on the chair and use the soap. He did and he seemed surprised at the sensitivity and within minutes a steam of white shot out of him. He was naively uninhibited in front of me and closed his eyes when he was softening. I watched this child. He spoke, “Do you ever have to do that?”

“George, every man does that. It’s called masturbating. It keeps a man healthy when he doesn’t have a woman to make love to.”

He looked at me puzzled. “What do you mean?”

“I mean most men would like to share themselves with a woman. That’s what Maggie does. She lets men stick their dick in her and move it back and forth until they come. Sometime men do it with other men but that is rare and illegal but men still do it.” I waited for his reaction.

“Maggie asked me to help this man once.”

“She said he needed help coming so she asked me to suck on his dick.”

“Did you do it?”

“Only after he bathed and cleaned up. I never told anyone I did it. She asked me if I was OK and I was fine. The guy seemed happy.

We were back in George’s room by the eight o’clock. I was relaxed and refreshed. George insisted that I lie down on his bed, and I fell asleep instantly. Later, I was gently aroused by George pushing and pulling of my shoulder.

“Seth, the 610 leaves before long,”

I heard George’s voice, but my body would not respond. The bed felt so good after so many hours a railroad car seat. He pushed my shoulder again.

“For where?” I mumbled. “What time is it?”

“After eleven,” he said.“Seth, I want to go with you. Do you think the circus would hire me?”

“They will if I tell them to,” I said in cocksure tone.

“Let’s get going,” he said. “I’ve got to unload freight before the train pulls out or Mr. Aston will be mad. I’ve got the team hitched, and Bill will drive them to Mr. Aston’s after we leave.”

His room looked cold and bare in light flickering from a coal oil lamp. I noticed that George folded a quilt from the bed and tucked it under his arm.

“My grandma made this quilt. Let’s go.”

He snuffed the lamp, and we walked downstairs. He never looked back. George and I boarded the 610, which departed at midnight. My head swayed from side to side as the train chugged through the desert blackness. I looked across the aisle and watched George sleep with his head on his quilt propped against the arm rest. He made me feel secure in a strange way, and that was why I agreed to let me join me. I needed someone who didn’t know the circus to keep me safe and he could protect me.

At two in the morning, we pulled into the Southern Pacific station in Modesto, and I tried to arouse George from a sound sleep. He jumped up ready to fight. His reaction eliminated any hesitation I had about having George along. Before we stopped, I spotted the third cut of the circus train on a parallel siding. From the station George and I walked back along the tracks to the loading area.

The block-in-tackle squeaked as ropes running between the wagon and the pull-up team strained to get the heavy, center pole wagon up the ramp. We watched the team settle the wagon wheels over the hump and then relax. Wagon 86 was on the flat car ahead. I knew I was home. Williams sat astride a pinto pony, with his left leg hitched up on the saddle horn. He carefully watched the action.

“Mr. Williams,” I shouted.

He looked our direction. In the darkness and shadows, I knew he couldn’t see who was speaking.

“It’s Seth, John S. Lloyd. I’m back. OK, if we hitch a ride. We can talk tomorrow.”

“Boy, get your butt over here,” he ordered. “I want to see you. You OK?”

George followed closely behind me. Williams dismounted and hugged me.

“Sure relieved you’re back. Good teamsters are hard to find.”

I was embarrassed at this strange show of affection from my boss.

“Mr. Williams, this is my friend George. Hope he can be my new assistant if and when I get a team again.”

“Boy,” he said sharply, “that black and white team better be harnessed by dawn’s early light.” “Whose been drivin’ ’em?”

“I think Topeka’s assistant, what’s his name? He will give 'em up to you.” I was glad he was so sure. I didn’t want a tussle on my first morning back on the lot. Williams turned to bark at a teamster hauling the poles.“Pick up the pace!” he yelled.

The teamster jumped because he was sleepwalking.

“Where to now?” George asked as the ramps were being pushed under the last wagon.

“Follow me,” I said with a happiness that comes from being warmly welcomed home after a long journey.

“We’ll sleep under 86 tonight. We’ll find the porter tomorrow.” George got on top of the flatcar and pulled me up. I didn’t use my leg at all. For a little guy, I was surprised by his strength. As I stood leaning against the wagon, I realized that I had been gone a month to the day. It felt really good to be back

Ten minutes later, the train whistle sounded and the cars lurched forward and then backward as we started our run to Fresno. To my surprise, my blanket was still in the box under the wagon. I offered to share it with George, but he pulled his favorite quilt out of a bag. He was like a child clutching his favorite baby blanket. With the white light of the moon George’s eyes became the size of saucers with every new sound or motion. I counted the stars and closed my eyes, listening to the clicks and clacks of the rails. The desert air was cold. All too soon the train ride was ending.

As the train slowed, the light moved inch by inch up the horizon in the eastern sky. There was no call to get up, so I assumed that the lot in Fresno was close to the train. George and I were up early because I wanted to find my team. We started toward the stock cars, and a straggly Negro boy stood at the door of car 101.

“Boy, is there a black and white team in your car?” I called up to him. He looked at us.

“Whoz you?”

“I drove the team before I got hurt,” I said.

“Oh, youz the one they try to kill.”

I watched George’s face out of the corner of my eye. He grabbed my arm. “Is it true what he said?”

“Yeah, for reasons that I can only speculate about, my assistant was killed, and I was thrown off the train. I’m sure they hoped I would be dead, too.” I was truthful with him because I needed him. I didn’t want to lie.

“Man, I take good care of them horses,” the Negro boy said.

“Are there four horses?”

“Yeh, man, Reel perdy.”

He gave us a toothy grim.

“But ain’t got no harness on.”

“Is the harness here?” I asked.

“No, man, They took it.”

Even if I didn’t get the new harness back, at least I didn’t have to retrieve my horses.

“Let’s go find us some harness,” I said to George. We took our time, watching horses unload two cars down. Only a few people acknowledged me. We saw Topeka’s assistant leading his own team so he obviously not going to drive mine.

“How’s it goin’, Bud? Good to see you back. Been strange around here last couple of weeks.”

It was busy. We couldn’t do anything about the harness until the blacksmith supply wagon and the horse tent were unloaded from the first cut. The clumsy, paint-chipped wagons were hooked and pulled across the flat cars as we watched.

First one, then another rolled down the ramp. A pull-away teamster dropped a ring on the hook on the end of each pole and pulled it ahead to a spot where four, six or eight dusty gray

Percherons waited. When the blacksmith wagon came down the run, I couldn’t see who had the lines. I hoped I would know the guy because I wanted to ride up top. Shooting pains in my leg told me it was still too early for me to do much walking.

“Mind if we ride over with you?” I called up to the teamster.“We need to gather some harness.”

“Sure,” he said. “Climb up, it’s easier on the right side.”

George was ahead of me extending a hand as I carefully worked my way to the top of the badly scared red wagon. Planks, ladders, and saw horses were haphazardly tied to both sides. The disorganized mess brought a smile to my face. Somehow men made harness, shod horses, and fixed metal gear with this jumble of equipment. For thirty minutes, George quietly paced around taking in each new sight and sound. He hadn’t said two words and all of a sudden let loose.

“Seth, we are along way up here over them horses. They going to pay attention? Watch them ears.”

We hit the railroad crossing and steel-rimmed wheels nosily crunched gravel and then slid across the rails. George thought that would be enough to send the whole team charging. They didn’t. George handled livery horses with grace and when he had the lines, his voice was calm and his words were spoken with assurance. But now he was unable to turn his head fast enough to see all that was going on. He chirped like a magpie with a hundred questions. The first day back was long and arduous. I did not see Raina and Rudi that day or the next.

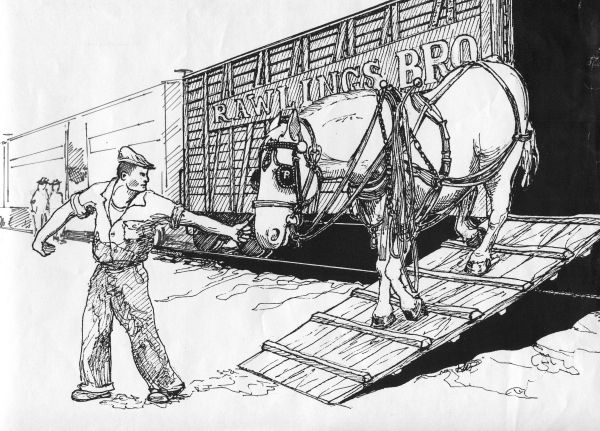

Seth Unloading Lead Percheron

By mid-afternoon, action slowed down. George and I collected the last few pieces of our harness. My team was ready even though deployment was not imminent. I wanted to be ready if the call came to load the cookhouse tent, which was first to be loaded. The team looked spectacular. More than three weeks out of the sun had allowed Travis and Indy, my black Percherons, to rejuvenate their shiny, coal-black coats. George agreed that I had the perfect team.

Brassy music announced the afternoon performance was beginning and mounted flag bearers started the procession of performers followed by the bears and then the clowns. The opening gave the audience a preview of who they were going to see. The performers hated the “spec,” as it was called, but smiled broadly because it was part of their job.

People moved around the lot slowly that afternoon because of the intense September heat. When the performance ended and the music stopped people began streaming out of the tent from all its orifices. Children pulled their parents to candy and souvenir vendors for a last taste or memento of the circus. The audience in Fresno had a distinctive Western appearance, with cowboy hats and broad brim hats. I learned that the farmers grew vegetables in the fertile San Joaquin Valley and shipped them all over the country.

I stood motionless in a sweltering daze puzzled by my surprised reaction to the performance being over. With my hand on Travis’ rear, she shifted from one foot to the other, and I knew she was ready to go. I waited until a familiar but unwanted voice broke my concentration.

“Butt-head has returned.” I ignored the comment.

“Farmer, wake up or someone will drive over your good leg.”

Ralph moved directly in front of me, and his breath reeked of cigarettes and onions.

“Sorry, your Kraut girlfriend is gone!”

It was at that instant that I realized that there had been no von Leuvenfeld music during the performance.

“Where’d she go?”

“You’re lover-girl and her paranoid, superstitious family left when we were in San Francisco. Stupid Krauts.”

Ralph stepped back. “Here to stay?”

“Yep, and I brought my own assistant this time.”

“Little fellow?” Ralph asked with a smirk.

“Big enough.”

I turned away from his sewer breath and misshapen, acne-pitted face and looked at my horses that stood quietly. Ralph walked off. I was shaking with anger at the thought that Ralph might have driven the von Leuvenfeld’s away. The sound of Travis scraping her hoof across the gravel brought me back. My attention was drawn to a sharp pain in my leg.

“That’s the way the circus is,” I said to myself with my teeth gripped together. The hot air seemed to have fingers poking me. I stripped off my shirt letting the straps of my overalls rest directly on my skin. The canvas fabric was coarse. I longed for a cool swim in Flat Iron Creek.

That first evening with George and the team was fun. I watched George’s excitement, which he tried not to show. At tear down, we hooked the first cookhouse wagon. I climbed up with a little pain in my leg as George firmly planted himself in front of the team. He backed the team, so he could easily attach the chains to the eveners. He bounded up the wagon ladder like a kid. His smile reached from ear to ear.

The horses strained and stumbled with the heavy wagon, but they never faltered. George and I endured a dust cloud that enveloped us as we drove. It soon became difficult to distinguish Whitey from Travis through the layer of grit. We stopped several times to give the horses a drink. The water washed the layer of dust from their throats and ours.

The train left for Bakersfield at midnight. In the cookhouse the next day, I overheard talk about who and how long it would take to replace the von Leuvenfelds. Most workers knew absolutely nothing about what had happened, but they freely speculated. The conversation shifted to movies and movie stars. It was rumored that the whole Rawlings family would be to hobnobbing with their movie star friends when we got to Los Angeles. Some of the men hoped that the stars would come to the performances so they could see them. We would be in Los Angeles for four days, the longest stop since Chicago.

George and I slept under 86 even though I had been able to get my old bunk and George as my bunkmate by slipping a two dollar bill to our porter. He liked me and was as happy to see me back as was Williams. Since Bakersfield we had only slept in the bunk one night and George accused me of never lying still. This night George and I decided we wanted to be able to see Los Angeles and chose to sleep outside. The night landscape was dotted by thousands of lighted windows the closer we got to the sprawling city. By dawn, hundreds of houses appeared as the train slowed on the east side of downtown Los Angeles. George and I lay awake for quite a while. Finally George ask, “Seth do you know what day this is?”

“Yeh, its Saturday.”

“I mean the date?”

After a pause I said, “Saturday the twenty-third. Why?”

“I can’t forget my mother’s birthday. It’s September 28. I’ll send a letter or a card. She’ll like that.”

Then we moved without speaking to the old “possum belly,” where we stored my blanket and George’s old quilt.

I crawled out from underneath 86 and walked to the back of the wagon. I stood there hitching up my pants. George joined me, and we watched the light spread over the faces of our audience. Hundreds of people gathered to watch the train unload.