Leaving Flat Iron Creek

CHAPTER TWO

Spears of lightning illuminated the southwest sky as we hurried to the Studebaker. Large drops of rain noisily pelted the shiny yellow hood as Thad sat in the driver’s seat and I stood on the passenger side of the Studebaker. Over the top of the door, I saw the menagerie tent sinking to the earth and felt a chill up my spine when it totally collapsed.

“Come on, get in. We’re ready,” Thad said loudly. “Seth, do you hear me? It’s going to rain. Let’s get going.”

I got in the car reluctantly and asked Uncle Harry how far we were from the railroad tracks. I wanted to come back to the tracks and watch the circus load and depart for South Bend.

“Seth, it’s going to pour,” Aunt Mildred admonished.

Uncle Harry said it was too far to walk and suggested that I take the car after dropping them off at home.

“If he wants to go, let him ride a horse,” Thad said sarcastically. Unaffected by his comment, I asked Thad if he wanted to go. “Maybe, I’ll decide when we get home.”

A few minutes later, Thad eased the Studebaker onto the macadam road and glided down Washington Street. I heard Mildred talking to Uncle Harry about the performance in the back seat, but Thad and I didn’t talk. He stopped the car outside the barn as the rain drops pelted the shiny hood. Uncle Harry and Aunt Mildred ran into the house.

We rolled the Studebaker inside the barn. I asked, “Are you coming with me? The rain feels good. It was stifling in that tent.”

He didn’t say a word as we fumbled around in the dark before finding an electric light string. We saddled the horses under the light from one dusty bulb hanging from the middle of the room. After switching off the light, we mounted our horses and headed toward the railroad tracks. We spotted a flickering, smoky smug pot on the side of the road.

“Follow these and I bet we’ll find ourselves a train,” Thad said.

We rode up an unpaved street passing a couple of houses with no lights before spotting a wagon with 86 painted boldly on the back door. Six wet draft horses slowly pulled the wagon through the rain.

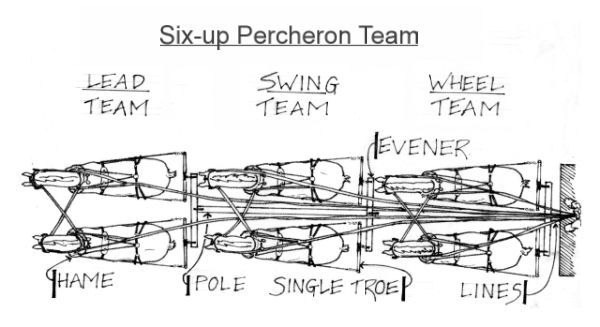

“What breed?” Thad asked. “Belgians aren’t white.”

“They’re Percheron. All circus stock is Percheron, originally from France, I think.”

A bolt of lightning and a huge clap of thunder spooked our horses.

“Could be an interesting night,” I yelled over the booming thunder clap.

Wagon 86 surged forward, but the driver had the team under control. “Barney,” he yelled, “Barney, get up.” The horse responded and immediately settled down.

“Guy knows his horses,” I said looking in Thad’s direction.

Percheron Six-Up Hitch

“Why am I out here, little brother? We could be struck by lightning. You are out of you mind.” He turned and I followed as we rode on down the street. We saw another smug pot. “Left corner must mean left turn,” Thad said with authority. We lay the reins on the right side of each horse’s neck, and they turned. Ahead we saw a team of eight blacks working hard to get the heavy wagon up the grade.

“I wonder what’s in there?” I said to Thad.

“Seat planks, damn heavy,” answered a man carrying a breaking block. We assumed correctly that he was to brake any backward movement if the horses stopped.

As the rain gushed down, Thad said, “Let’s go back.”

“Go ahead, I’m staying. I want to see how they do this.”

“Do what?”

“Get all this stuff out of town. They’re supposed to be set up in South Bend by eleven in morning,” I answered.

We stepped our horses off the road as another clap of thunder rumbled across the sky. Our horses stood calmly when we heard, “Tompkins, drop the block and grab Tommy’s head.”

With the next clap of thunder, the wagon stopped and lurched slightly uphill. Tompkins was only half-way to the lead team when the wheel team stepped back. The driver yelled, “Tommy, Bert. Goddamn, step up, step up. Tommy, Tommy.”

The brakeman, who sat beside the teamster, turned the red brake wheel furiously. But the brake shoes did not hold and the wagon wheels squealed as they rolled slowly backward. The wheel team closest to the wagon was forced right because a pole swung in that direction as the wagon inched toward a ditch swollen with rain water.

“Set the brake, dammit,” the driver screamed. “Step up, Tommy. Step up.”

“I’m trying goddamnit. It won’t hold.”

I got off my horse and threw the reins to Thad. “Hold him. The guy needs help.” I ran to the right lead horse, grabbed a bit, and tried pulling it while at the same time speaking calmly to the horse. In a flash of lightning, I saw the wagon drop into the ditch. The massive wagon stopped and rested precariously at a fifteen degree angle. Slowly it began to sink as rain water poured down the ditch. I held a bit in each hand. Men ran up the hill and converged at the back right wheel.

Thad jumped off his horse, tied our horses tightly to the fence, and ran to the back of the wagon with the others. A few minutes later he came up to me. He started to speak, but first blew the drops of water off of his lips and brushed his wet hair out of his face. “Let’s get out of here,” he shouted. “They’ll be working on that wagon for hours.”

A man dressed in a heavy rain poncho rode up on a brown and white pinto pony. He didn’t seem to be too concerned about the stuck wagon and ordered teamsters to maneuver other wagons around it and move their loads to the train.

“Get to your wagons,” the boss ordered. “We’ve got to get out of here. The loading area is soft.” Then he turned to one man and asked, “Topeka, you got the new six-horse hitch or your regular.”

“The new one,” Topeka replied before addressing an older man with short white hair. “Shorty, bring your team up. Be ready to hook to the right forward ring.”

Shorty dismounted, examined the incline on the right, and shook his head negatively.

“Your team can’t do it?” the boss asked

“Nope. There’s no way my team will be able to pull it out, Mr. Williams,” Shorty said.

“Then Johnson’s eight.” Williams barked. “They could do it. Where are they?”

“Probably coming back from the train,” Shorty said. “He was ahead of me with tents and probably went back past the school.”

“Who’s behind?”

“McCann’s with dem poles, three or four blocks back,” spoke a Negro without looking directly at Williams. The boss paused momentarily about fifteen feet away from where I stood holding Bert and Tommy.

“You,” yelled Williams to a Negro wearing a tattered undershirt, “Yeh, Nigger! You! Go tell McCann to pull the poles over. Tell him to bring his team up here. We’ll try to get the others by.”

Williams looked my way and noticed the fidgety horses. “Boy,” he said, “can you hold onto those leads?”

“Yes sir, but I’m concerned that the right wheel horse is squeezed,” I said. “Any way to straighten the tongue? Then they’ll stand all night.”

He stepped the pony back. I couldn’t hear what he said. In a matter of moments, eight guys stood at the right front wheel while a driver held the lines in his hands. Slowly, they worked the tongue over about two feet.

Williams rode back to me. “Pole straight enough.”

“We’ll hold no matter what passes,” I said.

Wagon 86 inched past us, with the driver keeping his wheels as far from the left edge of the road as he could. The hubs of the two wagons cleared by eight or ten inches. I spoke frequently and calmly to the lead horses whose bits I held firmly in each hand. I saw fear in their eyes as the other horses passed. A crashing clap of thunder surprised me as much as it did them. They surged forward but only took up slack. The wagon didn’t move. A string of three wagons with jungle cat cages hooked in tandem passed us. The wagons had new rubber tires, and four dapple gray Percherons did not have trouble getting by. A seat plank wagon followed, which was less bulky than 86 but still heavily loaded. A driver they called Topeka drove a young team of six blacks slowly up the hill, never taking his eyes off of his leads. He constantly talked and encouraged the horses as they slipped by us. Topeka slowed only after he was over the crest of the hill.

Thad carried the brake block for Topeka’s wagon. As he passed me, he said, “I wasn’t going to let you have all the glory.”

Williams barked loudly in my direction, “Goddamn, where’s McCann?” No one answered. Williams stepped his pinto backward as a wagon load of canvas pulled by six grays straining against their harness passed. The horses pulled but never faltered as the hubs almost scrapped.

Williams paced his pinto back and forth, looking for a team that never appeared. He looked toward me and our eyes locked. “Boy, go see what’s taking McCann so goddamn long.”

“Yes sir,” I said as if I worked for the guy. Thad hadn’t come back so I checked to see if our horses were still tied to the fence. My glance caused the man to look in the direction of our horses, too. He realized I wasn’t part of his crew, but he said nothing as I ran down the hill. I did not see a big team, and ran two long blocks. I passed several four-ups pulling equipment wagons and yelled to the first driver, “Seen McCann.”

The driver spat a wad of tobacco juice. “Who wants to know?”

“Mr. Williams.”

“McCann is back about a block,” the guy called back.

I kept running and soon saw horses. They pranced nervously. I walked up to them and firmly said, “How goes it boys.” I assumed the leads were geldings. My voice comforted them. I finally got to the men standing near the front wheel of the giant poles wagon. A skinny fellow with a straw in his teeth sat high atop the wagon in the driver’s seat. His sideburns came down to his sharp jaw line, and a Fedora hat sagged from rainwater. He held the lines firmly in his hands. No one moved to unhitch the team.

“Sir, Mr. Williams sent me to see if you would bring your team up for a rescue operation,” I said firmly.

“Yes, I heard that Mr. Williams wanted my horses.”

“There’s a wagon, a heavy one, off in the ditch,” I replied.

There was a long, agonizing pause as I stood looking up at his gaunt silhouette. “Son, I can’t make it. Tell Mr. Williams that he’ll have to find Johnson and his eight or somebody else.”

“Do you want me to give him a reason, sir?” I said.

“Son, just get along now. I’m not of a mind to explain to you. Why are you so intent on me being a good Samaritan?”

“I just thought we could help the guy out.”

“If you are so set on us helping, hoist your tail up here beside me,” he said in a tone of my eighth grade English teacher.

I stepped on the wheel spoke, then onto a step, and finally up top on the driver’s perch. A glance over my right shoulder confirmed the size of the giant center poles. There were five poles. I had noticed earlier that four poles were used to hold up the main tent and presumed the fifth was a spare.

The man next to me spoke first. “McCann is my name. What’s yours?”

“Seth Newman,” I drawled.

“Well, Seth Newman, can you drive?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Ever drive a team of eight?”

“Yes, sir. I have driven six and nine, three abreast.”

“Seth Newman, circus workers help each other,” he said, handing me the lines.

Only a few moments earlier, this man hadn’t seemed the least bit interested in helping anyone. I simply nodded and organized four sets of lines in each hand. I fed them up from the bottom, pulled the slack across his lap, and dropped the extra length over the back of the seat on my right side.

”Ready, Mr. McCann,” I said. “What are the names of the lead horses? Do you gee and hah them or something else?”

McCann smiled. “Seth, you ask the right questions. Ted is the left lead. Barney, the right. Their names mean left and right to the team. Step them out.”

My heart pounded like a bass drum. “Where’s your brakeman?” I said.

“He disappeared when the storm started,” McCann stated matter-of-factly, taking the great iron wheel in his grip. “Step them up, let’s go.”

I spoke Ted’s name first because we had to get to the center of the street. He responded, as did the other horses on the left side. Barney’s name came out of my mouth. Eight sets of hooves dug in, and the poles slowly moved. There was tremendous pull on the lines and the steel-rimmed wheels. The wagon vibrated as we rumbled toward the concrete grain silos ahead of us. The closer we got to the accident site the easier the horses pulled.

“Prepare to turn left,” McCann softly spoke. We saw the wagon off the road. “Is the ground firm enough to stop them before the hill?”

Without taking my eyes off Barney and Ted, I said, “Yes.” Several men walked beside the wagon as we completed the turn. Williams rode in our direction. The pinto slipped as Williams pulled up beside us. Luckily, the horse and Mr. Williams stayed upright. “McCann, goddammit, where have you been?”

McCann replied calmly, “I’ve been sitting up here waiting for you to come by and fire my ass. Mr. Williams, if I had descended this seat, I would never have gotten back up here. My arthritic knees would not have permitted it. I found this boy walking along the street and he agreed to drive my horses for me.”

Williams glared at us for a moment. “Can he handle ’em?” he snapped. “We’ll talk about your sad sack crap later.”

“He’s a natural,” McCann said firmly. Williams grunted and rode back to the wagon. “Seth Newman, now you must prove you are a good teamster.”

McCann looked toward the men on the ground, but didn’t see a familiar face. “Get the rope out of the front box,” he said, “Get down and get ready.” I felt confident even though I wasn’t quite sure how this whole thing was going to work.

My brother came up to the wagon just as I put a foot on the ground. “Thad, help me with the chains.”

“Why?”

“I’m going to drive this team and help pull the wagon out of the ditch.”

“You’re shittin’ me,” he said giving me an astonished look. “No, you’re not shittin’ me.”

He bent over and picked up the hook. Other men unhitched the team and waited for me to drive the team forward a few feet so Thad could attach the rope to the pull ring. I had the lines in my hands and I called for the leads to step up. They did their part perfectly and responded to my “Stop” command instantly.

Instead of mounting one of the slippery wheelers, which I would have done if we had going any distance, I walked the one hundred yards. When I called “Ted, Barney, step up,” their ears peaked and immediately responded. The tugging made the front left swing horse behind Ted nervous. He stumbled and caused the team to pull left momentarily, but they straightened out quickly.

My hands worked furiously to get the lines properly organized. My eyes never left the tail of the two wheelers. I didn’t see the heads of the leads, but knew Thad was up there with them. When we were beside the wagon, I pulled the team to a stop with a long, loud “Whoa.” The Negro I had seen earlier attached the hook into the ring on the front right corner of the wagon while Thad placed the hook into the ring on the evener. We were ready. As the rain clouds dissipated, I noticed how the moonlight illuminated the haunches and shoulders of the two horses nearest the wagon. Their tremendous power was in my hands and ready to be released on command.

“Kid, pull up,” Williams ordered. I stopped immediately and saw Thad ahead ready to catch the lead’s bits. “Kid, you ever pulled a load ’a logs? Moving this wagon will have the same kind of drag. I want this to work the first time.” He looked apprehensive.

Moving my team along side the other team made me realize just how little room there really was. I looked carefully to my right.

“Can I drive them off the road?” I called up to Thad. “Is the ditch over there very deep? What if I swing the lead horses to the right ten or twelve feet? What problems will we have?”

Without giving an answer, he ran to the ditch to check. “If you’re thinking of driving off the road, I think it’ll work. There’s plenty of gravel out front.”

Williams checked the hook in the ring at the right front corner of the wagon. The driver and brakeman sat atop the wagon. The horses pranced nervously, sensing our tension. Negroes positioned themselves behind the wagon and on the right wheel, their massive black hands gripping the spokes and wheel rims. I wanted a slight right pull as we went forward because I felt that the team would naturally pull to the left.

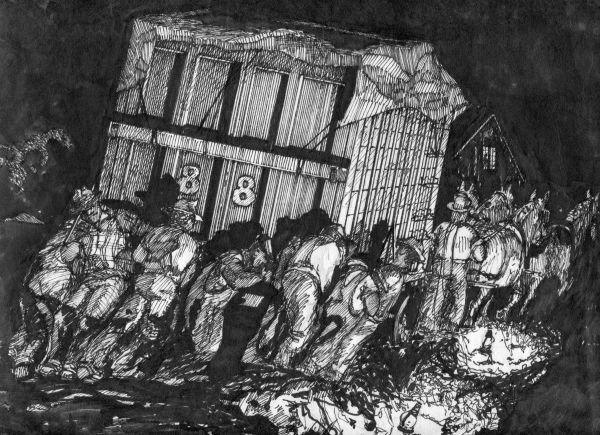

Moving Wagon #88 from the Ditch

“Let ’em go,” Williams hollered.

The other driver said, “Ye, ha, gitty up.” His team straightened and suddenly yelled, “Whoa… Goddamn chain is loose on a front swing. Get in there.” Several men crawled under the horse to reattach the chain.

Everyone relaxed momentarily. “Ready,” Williams called loudly. “Try it again.”

The driver let out, “Gitty up, gitty up.”

As the other team moved to tighten up the chains, I called, “Barney, step out. Barney. Ted, step up.” They responded perfectly, and their chains spread to full tautness. The poles lifted off the ground to mid-thigh, and the hooves dug in for traction. Slowly, the wagon began to move.

With the horses struggling and straining, I called, “Barney, Bane, Buster. Step up, step up.” They gave it their all. The reins in my hands were taut. I tried to make sure I did nothing to restrain them and felt a surge forward when the wheel was back on the road.

“Keep going, don’t stop.” Williams yelled. I tightened my grip on the left reins as I said, “Ted, over.” He and the others on the left pulled, and the team followed. It was barely twenty yards to the crest of the knoll, and I watched carefully to ensure that my wheelers didn’t get to close to the other team.

At the top of the hill, I stopped the horses, and the brakeman set the brake. Williams called to me, “Back ’em!” I did, and the tension eased on the hook. It was quickly removed. “Take ‘88’ to the train. Tell the train master to load everything he can, and we’ll have the poles there within a half-hour. Tell him poles will be fine on 101. I’ll be there soon,” Williams called to the driver.

He turned to me. “Listen, kid, get McCann’s team back down the hill. They got enough left to get the poles up the hill.” He moved away before I could answer. The turn was tight, but we inched around and made it. Fifteen minutes later, McCann had his horses hooked and ready to go. He held the reins in his hands and said, “Seth Newman, climb up and ride with us to the yard.”

“My brother, too?” I said.

“Certainly. Let’s go.”

The team had plenty of power left as we sailed up the hill. When we got to the loading yard, McCann pulled the team twenty yards in front of the run that would guide the pole wagon to the top of the flat car. The poles were secured on the train. Thad and I stood with a dozen men until after midnight, when the final wagon was loaded. I was too excited to be tired. The sleek black body of the Pennsylvania Railroad engine chugged slowly backward with the slap of metal to metal signaling that the circus was ready to leave town.

As Thad and I walked to our horses, Williams hollered, “Kid, you want to be McCann’s first assistant? Job’s yours. Three dollars a week with bunk and meals included. You did OK.”

Williams turned and caught the hand rail of a Pullman as it slowly passed him. He never looked back, and the train slipped off into the night.

A chill gripped me as I mounted Best for the ride back to Aunt Mildred’s. The cool night air crept into my soaked clothes, taking away the wonderful warmth I felt minutes before. The moon illuminated our route to the house. The silence was disturbed only by the clicking of the horse’s hooves. We rode into the yard without saying a word.

On the back porch, we pulled off our clothes and hung shirts, pants, and underwear on a towel rack. Thad grabbed a dish towel to cover himself, but I didn’t find one and slipped upstairs hoping no one was wake up.

But pajama-clad Uncle Harry turned on the lights as we hit the landing at the top of the stairs. “Hi, boys, lose something?”

“Left our wet clothes on the back porch,” Thad explained.

“Fine, fine,” Uncle Harry said as he led the way to the sleeping porch. He opened the French doors and a gush of warm air hit our cool bodies. He flicked on a small table lamp right inside the door, but the light was not strong enough to illuminate more than the side wall. Uncle Harry was unconcerned about our nakedness; I guessed as a doctor he sees patients this way all the time. He opened the tall porch windows, and the cool night air rushed in. Thad and I watched him, not knowing quite what to do.

“Busy night?”

“Yes, sir, but fun,” I replied.

“Want a shower bath?”

“Sure,” Thad said. “Will it bother Aunt Mildred?”

Uncle Harry shook his head slowly and led us to the bathroom which had a built-in shower. I stepped inside the shower first, and the warm water felt wonderful.

When I finished, I saw Uncle Harry examining Thad’s left knee, the one that had gotten him discharged from the army. He gently rotated the knee with his right hand while his left was behind Thad’s knee.

“Good body, well-proportioned, good stud.” I said laughingly, “Laureen’s a lucky girl.” He looked over his right shoulder in my direction. “What’d you say? What are you looking at?”

“Your butt,” I jabbed. “I was thinking Laureen’s a lucky girl to get a hunk like you.” Thad blurted out, “If you join the circus, there won’t be any more nice warm showers.”

That was Thad’s way of letting Uncle Harry know that I might leave home. Harry would tell Mildred, who would eventually tell Mother.

“Sorry,” Thad said reluctantly. He turned back to Uncle Harry and recounted the night’s events concluding with my job offer to be McCann’s first assistant.

“Good opportunity,” Uncle Harry said. “Are you going to take it?”

I didn’t answer. Uncle Harry, who had been sitting on the toilet seat while doing the examination, stood up and walked toward the open door. He put his hand on my shoulder and warmly said, “Good luck with your decision.”

After my head hit the pillow, the next sound I heard was the slam of the screen door on the back porch the next morning. I walked to the window to see Aunt Mildred’s housekeeper hanging our clothes on the line and realized Thad and I had one pair of boxers between us. I reached for my overalls, leaving the underwear for Thad, when Uncle Harry walked in carrying several pair of cotton boxers.

“Need these.”

“No, but Thad will.”

My brother opened both eyes. He threw back the sheet and sat up. “Thanks, Uncle Harry. Do you have an old shirt and pair of pants I can borrow for a little while.”

“I’ll be right back.”

Uncle Harry seemed to relish our company. Both daughters, Hope and Eileen, had already left home. Hope married a Boston lawyer after graduating from Mt. Holyoke College. Eileen, a sophomore at Smith College, was in Europe for the summer. I think he was lonely. We talked briefly after Uncle Harry returned with the clothes, and then he told us he was on his way to see a patient who had fallen off a hay wagon, breaking a hip and a leg. Uncle Harry said the guy was in traction in the hospital.

Thad and I had not spoken. It was a breezy, sultry morning, and we sat on the screened porch eating eggs, bacon, toast, and coffee prepared by Aunt Mildred’s housekeeper. Aunt Mildred stopped by to say good-bye and was off to a meeting to plan the Fourth of July celebration. We thanked her and gave her a hug.

I sat back in deep thought when Thad said, “Are you going or staying.”

“I don’t know, I’m thinking,” I whispered.

There was an uncomfortable pause as we took bites of egg and sips of the steaming hot coffee. I spread fresh strawberry jam on two slices of toast. The knife raked across the top of the toast, adding to the strained silence between us.

“If you leave, it’s going to be hard on father,” Thad said. “You’ll leave two of us to do the work of three.” He sat back with a cup of coffee clasped between his two hands looking squarely at me.

“I could send money home. Father could hire someone to help. Thad, I really want to go with them.”

“Why do you get to leave and I have to tell them.”

Thad revealed his true concern. He didn’t care if I stayed or left home. He just didn’t want to be the one to tell our parents.

“They’ll blame me for not talking you out of it.”

“If father needs me at harvest, I’ll come home. Tell him that.” I knew my decision was final. With my heart pounding, I blurted out, “I’m going. Let’s get to the depot to see when the next train leaves for South Bend.”

Thad frowned, but I saw the tiniest tinge of relief on his face. We finished our breakfast, gathered up our clothes, and rode to the train depot. I planned to stay at the station while Thad rode home with the horses. The plan faltered when we discovered that the next train did not leave until three-thirty. As we tied the horses under the branches of a giant sycamore, we reminisced about the circus we saw years before with Aunt Mildred, Uncle Harry, and their girls. The conversation quickly became a game of one-upmanship.

“Remember the chariots careening toward the crowd screaming for them to go faster? And that gladiator wearing a helmet and kilt. He would have been dragged by the lines if he hadn’t caught the handle on the side of the chariot,” Thad said.

“He didn’t fall off. I know he didn’t.”

“I know he didn’t. But he almost did and probably would have been crushed under the hooves of the horses behind him,” I countered.

“They were racing to win,” Thad said. “I thought it was just for show, but they were really racing.”

We tried to out talk each other as we walked across the patterned stones that defined the turnaround in front of the low brick structure that was the Pittsburgh and Ft. Wayne Railroad passenger depot. The curved terra-cotta roofing tiles, some lighter and some darker, were arranged in a diamond pattern. We entered the double screen door on the left that led into the sandwich shop.

As Thad grabbed the left hand door handle, forty flies scattered. I stepped ahead of him as he recounted the antics of clowns that had the crowd belly laughing with comic skits.

“The acrobats,” I interrupted. “Do you remember the eight or ten men and boys with the billowing white shirts and red shoes? I had never seen such spectacular flips and twists. I can still remember the kid that flew off that teeter-totter and landed on the shoulders of a guy who was perched on two other guys. I was sure he would have killed himself if he missed.”

I followed Thad to a table with four white chairs tightly pushed against stained linen adorned with a metal topped sugar dispenser, mismatched salt and pepper shakers, and milk pitcher whose rim was the resting place of two flies. Thad drew back the rounded chair that faced the counter, flung his left leg over the top, and solidly dropped his butt onto the plank seat. He talked, and I half-listened as he recalled the terror he felt as a uniformed man entered a cage with ten or more leopards. A shiver ran up my back when I remembered how the man attempted to get the sly, spotted predators to do tricks.

A waitress, wearing a stained white apron around her waist and a gingham kerchief on her head, stepped toward us. She had two white porcelain cups in her right hand and a tall, blue-white speckled coffee pot in the other.

“Almost missed lunch. Want coffee?” She spotted the flies on the pitcher rim and set the cups down. “I’ll get some fresh milk.”

I quickly said, “Don’t bother. Neither of us uses it.”

“You want something to eat?”

“I want a bologna sandwich with mustard,” Thad said. “Got any sliced pickles?”

“Yes, I do,” she snapped.

“Put cheese on my bologna. No mustard. White bread,” I said.

Although Thad never looked at the waitress, her body movement told me she longed for him to pay attention to her. She turned and walked away.

Thad looked squarely at me and said, “When was that?”

“When was what?”

“When did Uncle Harry and Aunt Mildred take you, me, Eileen, and Hope to the circus the first time? Do you remember?”

“I remember that we had been staying with them for several days. That was the time you spied on Eileen when she was taking a bath.”

“Oh, yeah. It was before the war in Europe started. The circus had a German name like Richenbach or Wallenbeck.”

“It was Hagenbeck, the Hagenbeck and Wallace Circus.”

“We must have been ten and eleven. Something like that. Do you remember the white bears, the polar bears? The trainer had a red coat that made him stand out against the backdrop of white fur.”

My mind wandered as Thad said something about horn-honking seals. My brother was a nice guy, a bit stubborn at times, but still a nice guy. He was my height, five-ten, but heavier. Maybe one hundred eighty pounds. I see his mouth moving, but my thoughts crowded out the sound of his words.

“What are you looking at?” Thad asked.

“Your mustache.”

“Not you too,” Thad groaned. “I didn’t shave it off for Father and I’m not for you.”

In addition to, mustaches Thad and Father argued about which crops to plant in which fields, how and what livestock to buy or sell, and even what to feed them. Their open irritation with each other did not prevent Thad and Father from working side by side. Their personal relationship was comfortably tense. Mother and I knew that their constant banter rarely turned nasty. We just walked away when a verbal altercation began.

Everyone knew that Thad would take over when Father retired. Thad liked farming. Thad’s relationship with Father was similar to Father’s relationship with our Grandfather. Pop, as he was called, openly and vigorously insulted Father at every opportunity. Grandpa did not respect Father, who had married his favorite daughter and, in Grandpa’s opinion, was not worthy of her. Thad saw that relationship since he was a small boy and fumed that Father would not strike back. After Grandfather died, Thad took Grandpa’s place when it came to arguing with Father.

“You don’t care about me at all? Think of the number of times I’ve saved your butt when you didn’t do your chores,” Thad mumbled. “You’d be wandering in the fields, and I’d be cleaning stalls and shoveling your manure. Now you want me to do your dirty work and tell our parents you’re joining the circus.”

The waitress put two white porcelain plates with our sandwiches on the table. “Seth, where the hell are you? Come back into the world,” Thad said.

“You boys want some pie? I got fresh cherry pie and, I think, one pie of chocolate.”

Thad went for chocolate, and I ordered cherry.

“I remember the trapeze acts. When the girls flew, they were birds. They let go of their bars and floated across the air into the hands of a guy who caught them. Then they’d fly back.”

Thad picked up my thought. “Yeah, they didn’t seem nervous wondering if the guy across the tent was going to be there. If I was a girl, I don’t know if I’d trust a guy. Except me, of course.”

I laughed and knew that Thad was more worldly than me. I knew he lost his virginity when he was fifteen, and I knew he had had several intimate girlfriends, because he told me about every single encounter. Like a hunter chasing his prey, Thad treated girls as conquests. I knew he might lose the current hunt.

He was smitten by Laureen, a smart and aggressive woman strongly motivated not to be a farmer’s wife. She was a sophomore at Ball State Teachers College in Muncie, Indiana. Thad’s challenge was to convince her that she could be a teacher and a farmer’s wife. She was a tiger to be tamed.

Thad munched silently as the depot shook and quivered as an eastbound freight ponderously rolled past the open windows. The soot-grayed curtains danced as the boxcars and hoppers sped toward New York. We didn’t speak for minutes. The spell was broken when the waitress set pie saucers on the table. She couldn’t remember who got chocolate or cherry so she set the plates in the middle of the table.

“Tell me again, little brother, how and why I get to take your horse home and tell Mother and Father that you took a train to South Bend to join the circus. Why should I do your chores? Why am I doing this?”

“Well, big brother, you want to be a farmer and I don’t. I want to go see what the world has to offer. I’ll come back, tell them I’m not leaving for good.”

“OK, OK, I hear the train. Pay the lady,” he said as he pushed himself back and started toward the door. The waitress stood over the cast iron cash register at the right end of the counter and rang up our thirty-five cent lunch, leaving me little more than a dollar to buy a train ticket to South Bend.

I followed Thad to the ticket window inside the depot. A squealing spring snapped the door closed as quickly as we entered. With a ticket in hand, I followed Thad’s footsteps onto the platform.

We exchanged a few words. Thad seemed sad but finally gave me a good luck handshake and surprised me by giving me a firm bear hug. I boarded the coach and turned to wave good-bye, but Thad had already left the platform.