Dmitri Goes to War

by Joe

graflz825@gmail.com

Foreword

There are a few historical personages, such as the Tsar and several of his admirals, who appear in this story. All of the other characters are fictitious and any resemblance to anyone in the real world is entirely coincidental. There are some real events in this story, the Battle of Tsu Tshima being one such event but the presence of our heroes is, again, entirely fictional.

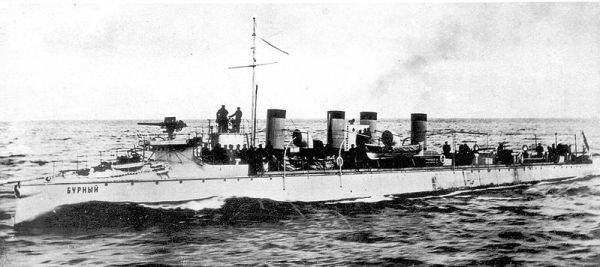

The Brilliant is a destroyer of my imagining and the name is arbitrary, in English, and not an attempt at translation or transliteration. The Borodino and the Izumrud are real and performed as described.

The complete command of the aristocracy over the lesser classes of society is difficult for the more egalitarian among us to realize. Russian serfs were emancipated in 1861 which would have been within living memory of people within this story. It should be remembered, that one princely family had sufficient spare resources to support a ballet troupe with orchestra and hall. Upon a command from the princely box the performers would retire to the wings and reappear nude. It was a different world.

Alan and Douglas have both assisted in the editorial process of this story and I thank them for their input and guidance. I sometimes take liberties with tense when it comes to attempting to set the tone of a character’s thoughts. If this offends, I hope you’ll forgive me.

If the thought of intimacy amongst persons of the same sex offends, one ought not continue with this story and should probably leave this site.

I welcome a reader’s comments on the story.

I hope you might consider supporting AwesomeDude. It is a delight and a treasure.

Tsar Nicholas II

We have been to see the Tsar. It was when we were rolling home across the sweeping grasslands of Russia to our estate that I began to wonder about the world, to wonder why, and to wonder about things well above my station in life.

We would be on the train for another day; then there would be two days by carriage. Normally we would have ridden the last two days on horseback because we love horses; additionally, it’s the thing when you’re young, and particularly as we always looked really good on our matched Arabs. They had matching tack and we had matching riding togs; but my Count was still recovering from the loss of his left leg below the knee. So it would be four wheels for him. He would carry on and insist that he wanted to ride; that it would be good for him to ride; that he was perfectly capable of riding; that it was essential to the greater glory of Imperial Russia that he ride. But our entourage would listen to me at the station. So, ultimately, would he. He would be able to ride again, but not until his stump had healed. We would take the carriage.

My Count lost his leg on the deck of His Imperial Majesty’s destroyer Brilliant the day after the Battle of Tsu Tshima. He was her Captain and His Majesty never had a finer man or sailor in his service.

The first day of the battle had not gone well. But what could you expect? We were exhausted: both the men and their ships. We had steamed half way around the world. We had no opportunity for major repairs or maintenance in a naval yard; no opportunity to dry dock and clean the barnacles and weeds from the hulls. Our ships were quite as tired as runners at the marathon finish line. Many small things were broken and could not be repaired and some more important things were barely working at all. We couldn’t even make our full speed. And we were tired too. There had been practically no shore leave, no rest, no holidays just the constant grind of the trip with all too regular stops to coal ship. As filthy and miserable a job as was ever devised. All too often we had to do this at sea where it took even longer than usual. Then there was the grinding tropical heat. There had been no really friendly port the entire voyage. We had stopped at the French Indo-China port of Cam Ranh Bay, but we could only use it for an anchorage. It was no sort of a base. We could do no repairs and the French were under international pressure to be “neutral” so they were very little help to us.

And so we met the Japs. They were all fresh, rested, repaired, exercised, experienced and ready. We still had tons of coal in sacks on the decks of some of our ships. It did not go well for us.

I did not see much of the action. There was some mist and fog, later there were clouds of gun smoke too. We were a small ship and close to the water. Even stationed on the bridge as I was, I could see very little. Besides, I was often dashing about as my Count used me as a reliable messenger. I remember seeing a huge plume of smoke and thought we had sunk a Jap; but I later learned I was wrong, it was the magazine of the battleship Borodino blowing up. We lost three more battleships that day.

There were several brisk destroyer actions and we were hit many times. We fell out of the fight for several hours when an enemy shell broke the main steam line and we lost steam pressure and so speed. One of our stokers had immediately shut the main steam valve in the boiler room, so our engineers managed to repair the line and we got underway again, but the action had moved away from us.

What was left of the fleet was, well, floundering around lost, scattered in bits and pieces. Some of it would actually surrender. Our engineers had repaired the main steam line, but it could no longer hold full pressure so we couldn’t make our full speed. Our torpedo tubes were jammed and twisted on their mountings; we’d had to jettison our torpedoes since they had ceased to be a weapon and had become a danger only to us. Of our two twelve pounder and four three pounder quick-firing guns, we now had only two three pounders serviceable and both of those were on our port side. Most of the crew were killed or wounded. So when two Jap destroyers came toward us, white bow waves flashing in the May sunshine, my Count called for the helmsman to turn to port and he ran to one of the remaining cannons and prepared to open fire.

“Dmitri! Make sure our flags are still flying,” he yelled to me as he fumbled with the breechblock. He fumbled a little because, after all, he was the Captain and not a Gunner. I ran aft a few feet and saw that we still had our battle flags flying, one forward and one aft. We’d lost the after mast on the first day of battle, so the aft flag was flying from the flagstaff on the fantail, which wasn’t regulation, but was the best we could do. Then I ran to the bridge, took the tie ropes off the wheel and put the helm to port as my Count had ordered. There had been no one at the wheel when the order was given.

CRAACK! The little three pounder snapped at the Japs. It wouldn’t do much, even if it hit an enemy, but it was the gesture that was important. I retied the helm and, scrambling around the wreckage of our gig, and avoiding holes and shattered deck plates, ran to assist my Count. He was reloading. I grabbed a broken piece of stanchion and pried open the jammed cover of a ready ammunition locker. We couldn’t accomplish much with a three pounder, but we’d have plenty of ammunition.

CRAACK! We got another round off.

“Look there!” Fjodor shouted exuberantly, “I hit the bastard!”

I looked up and there was a trail of smoke from just forward of the bridge of the lead Jap destroyer.

“Helm amidships,” he yelled to the bridge, so I ran back to the bridge, untied the helm, swung it amidships and retied it. Then I saw young Serov, one of our loving young seamen. He looked shocked, but aware. “Mind the helm,” I ordered him, “Thank God you’re not hurt. His Honor intends to fight the ship.”

“Yes Dmitri,” he was visibly pulling himself together.

CRAACK! Went the cannon and Serov leapt to the wheelhouse while I ran back to the gun.

It was at that moment that the Japs opened fire and their shells swept into and over the Brilliant. She staggered beneath my feet under the weight of the shellfire. I was thrown to the deck as a great gout of steam and smoke belched from the second funnel and several hatches and one of the engine room ventilators. I could tell from the vibration of the deck that the engines were giving up and we were slowing, if not to a complete stop, then to a speed so slow that it may as well be a complete stop, because there would be no way we could escape the trim Jap destroyers, much less make it to Vladivostok.

Earlier, the beautiful cruiser Izumrud had gone past us; she was making turns, with a bone in her teeth, and a curling wake beside and behind. All her flags had been flying and she was glorious to behold. She’d signaled us to take station ahead, speed 20 knots. Sadly, we’d replied, that the best we could do was 12 knots. After a short pause, she flew the signal: “Proceed Vladivostok. God Speed.” We acknowledged, as she was the senior ship and we’d had no signals from anyone in command since yesterday; we watched her tear away to the north. I’ll always remember her. She could have waited.

Izumrud [1]

We later learned that she had refused Admiral Nebogatoff’s order to surrender to the Japs and left for Vladivostok on her own volition. That was a grand gesture. Sadly, she ran aground trying to make it into port and was lost.

‘Well’, I thought, ‘this is the end for us.’ I was just twenty-three, and my Count — my life and love — just twenty-four. I regained my footing and ran back to my Count who was sprawled beside the wreckage of the little three pounder with blood spurting from his shattered left leg. He was barely conscious. I pulled off my jumper and used it as tourniquet around his leg above the knee. The spurting stopped, thank God and good Saint George, but he was still bleeding, so I pulled off my trousers and rigged a pressure bandage which I wrapped tightly over his wound though it was obvious that he was going to lose the leg and possibly his life. I prayed. I prayed for him and, if truth be known, I prayed for me, for he was a part of me.

The poor faithful Brilliant, as feared, had come slowly to a stop and we were wallowing in the gentle swell; wallowing in a cloud of smoke and steam with the taste of coal dust everywhere. Serov came down from the wheelhouse to be with us. We kissed. If there was anyone else of the crew still alive, I couldn’t see or hear them. I very much feared that the rest of the engine room staff were dead. Someone had been stoking coal and keeping us moving. I prayed for them. They had brought us halfway around the world in the blistering heat of the boiler and engine rooms, only to end, almost as an afterthought, in a blast of steam and steel fragments. The Japs had stopped shooting and one of the destroyers came slowly by less than fifty yards[2] away. Several of them were yelling and pointing. I didn’t understand them, and all I could see when I looked where they were pointing was our ensign and I wasn’t going to take that down without His Honor Lieutenant Count Fjodor Gregorovich Berdyaev said to. To make this clear to them, I reached down and pulled his dirk from its scabbard and waved it over my head.

His Dirk

So there we were. The Japs were lowering a boat and would soon be boarding us. They’d probably kill us at once. Even if they left us alone and sailed away, the Brilliant was clearly sinking and when she left us we’d be alone in the cold sea, thousands and thousands of miles from home. Serov and I started saying our prayers in the proper way. I bent over and kissed my Count. Serov did too. Then we stood there waiting to die. I was wearing a singlet, a torn pair of the silk drawers my Count had given me, and the Saint Andrews medallion he had given me years ago when first he enlisted me in his service. Serov was in the tattered and smoke grimed remnants of his white uniform. He had lost his shoes somewhere; somehow, he was still beautiful and he looked at me hopefully, as if I knew what to do.

The Jap whaleboat came alongside, and a boarding party clambered aboard in a professional and seamanlike manner. My Count would have approved even if they were the enemy and were about to send us all to heaven. The leader of the Japs had an officer’s tunic on and was carrying a sword. The others all had rifles or pistols and were wearing their sailor’s uniform, which was, all things considered, very like our own.

The officer stood there and yelled at us in his gibberish. Serov and I stood there, waiting to be shot. There was nothing that we could say or do. Finally, he drew his sword. ‘Oh shit’ I thought to myself, and put my arm around young Serov. But instead of chopping us down, he pointed his sword at my Count’s dirk that I was still holding. Then, carefully and with great exaggeration, he sheathed his sword. Well, I thought, maybe we’re not going to die just now. I leaned over my Count and put his dirk back in the scabbard at his belt and stood back up with empty hands. I pointed at my Count’s leg and started yelling at them that he needed a doctor. I used every word, in the three languages that I knew, that had anything to do with healing, I even yelled “veterinary” at them. They understood my actions if not my words. One of them started examining him. Others started off in pairs to search the ship. The officer went over to the mainmast, and cut down our battle flag. He bundled it under his arm; he looked at me, pointed to my Count and asked “Captain?” I nodded and gave him my Counts full name and titles. He seemed satisfied and handed the battle flag to me after wrapping my Counts dirk in the flag, gesturing that I should give it to my Count at some later time. I felt good. I had expected to die. But at least for now, we were going to have a little more time. I had never had a feeling quite like it before. It was good: joy seasoned with relief tinged with worry for my Count. The officer then went aft and cut down our other flag. His ship’s whistle sounded when our last flag came down.[3]

That’s why we went to see the Tsar in Moscow. The Japanese thought we were pretty noble. Not merely brave, but also loyal. A feeling I’ve come to understand they put great store by. Standing by our wounded officer and refusing to surrender appealed to their tradition. In fact, they took very good care of all of us they took prisoner. They nursed our admiral back to health. Our admiral was a fool. My Count had said so many times during our voyage so that settled the matter for me. They had Serov and I take care of our Count as he started to recover; they told everyone how noble we were. All things considered, if you have to lose a battle, best to lose it to the Japanese.

That’s why the Tsar wanted to see us. He had all three of us brought into the throne room. Our Count was in a wheelchair, with Serov and I standing on either side, the three of us in immaculate new uniforms. He personally decorated me and Serov with the Saint George Cross (Fourth Class) and he awarded the Order of Saint Vladimir (Fourth Class)[4] to our poor Count who was as close to heaven at that moment as it is possible to be while remaining in this world. I was proud of my Tsar and proud to have served him.

The Tsar was immaculately turned out, and I suppose that someone, somewhere, knew what all of his medals and orders were about, they were profuse. The throne room was incredible. Marble pillars, painted ceilings, ornate molding, complex parquet floors, and carving everywhere. Huge paintings of Tsars and Tsarinas hung on the walls interspersed with the occasional battle where men like the crew of the poor old Brilliant fought and died for their Tsar as we had for ours. It was only after we’d been ushered out of the room that it dawned on me that I’d not seen a throne. I asked a footman about it and the man attempted to sneer and ignore me simultaneously. He doubtless thought he was superior to me. I repeated the question in French; called him a cretin, threatened my Count’s vengeance, and used the familiar form of address. He cringed and explained that it was really only an audience chamber and the real throne was in a different room altogether. He begged my pardon. I smiled and thanked him, feeling vaguely cheated by the lack of a throne room for my Count’s ceremony.

You could tell that the Tsar was off his feed. He had bags under his eyes and while his beard and moustache were beautifully trimmed, he still seemed to be frazzled. It was strange: it was obvious that he was pleased to have us presented to him; that he was genuinely proud of us and the service we had rendered him. However the weight of his responsibility to our nation was clearly weighing heavily upon him. Some burdens can only be carried by the Tsar.

We peasants have always been taught to think of the Tsar as ‘Our Little Father.’ I certainly thought of him affectionately as he had smiled and clipped our medals to our tunics. We were happy that he was proud of us too, because, as the Good Lord knows, the poor man did not have much to be proud of in the last few years. True, the Tsesarevitch was born in 1904: but then everything went downhill fast, we lost the war in the next year, and that was quickly followed by riots and mutinies and hunger and talk of revolution. People were sullen and we felt it all across Russia as my Count slowly regained his health. We had spent several months in the naval hospital and a pensione in Vladivostok before starting home by rail. I sometimes had to be somewhat forceful in order to ensure first class accommodations for my Count. There was this strange feeling everywhere, as if something was not quite right, but it wasn’t wrong enough, somehow, to really know exactly what was wrong or how to fix it.

I looked around our compartment. Little Serov was dozing on one of the bench seats. Our Count was dozing in his wheelchair. I checked again to ensure that the wheels of his chair were locked so there could be no accidental rolling. The train was gently rocking.

I watched our beautiful country roll by the window and I thought back to when first I met my Count.

The poor faithful Brilliant [5]

++++++++

I was twelve years old and had stopped by the village well and was holding a dipper of water ready to take a drink. He came clattering up on a beautiful black and white pony. The pony had clearly been running, but she was breathing easily; she’d enjoyed her run, she’d not been overwrought. He looked me in the eye, his blond hair going every which way from the wind of his ride. He’d not been wearing a hat. His nose was straight and his eyes were blue. He reminded me of the icon of Saint George in our little church.

“You,” he said pointing at me with a silver mounted riding crop that had been tucked in his boot and not used on his pony. He used the familiar form as was proper for the nobly born to a peasant.

“Yes Your Honor,”[6] I replied. I just naturally assumed he was thirsty so I took my dipper of water over to him and held it up for him to take. He looked at it, and at me, for what seemed the longest time.

“You drink first,” his smile was dazzling.

I took a tiny sip. Then I thought he’d not want to drink out of the dipper I’d used. “I’ll get you some fresh water Your Honor.”

“No! No! Take another sip. You’ve offered me your water. That’s a grand gift. It is genuine.” I took another sip and handed him the dipper. He swallowed it down and gave me back the dipper.

“More Your Honor?”

“No. Thank you. That was very good indeed. What’s your name?”

“I’m Dmitri Mikhailovich Dyachkin Your Honor.”

“Do you live here, Dmitri?”

“Yes Your Honor, just down the road there. My Da is the smith.”

“Excellent, that means you’re my man. Of my estate. Can you ride Dmitri?”

“Yes Your Honor.”

“Good. Climb up behind me,” and he reached down and I was up behind him in a trice. “We’ll ride down to the river,” and we were off at a walk. “Don’t be scared. Grab me around the waist and hold on. We won’t be walking all the way.” I circled his waist with my arms, he felt good.

‘Don’t be scared,’ he said. I was thinking, ‘that’s easy enough for him to say’. But I was plenty scared. In fact, I really was for all intents and purposes, ‘his man’ of ‘his estate’ and if his intents and purposes were bad, there was nothing much for me to do but pray. I decided to pray to Saint George as we cantered down the path.

He obviously knew his way around for I barely had my prayer organized, much less actually said, when he pulled up at this small meadow that slopes down to the riverbank. It was late in the year and the river was low so there was a nice stretch of sand before the river.

We dismounted. He rummaged in his saddlebags and handed me a halter. I slipped the bridle off his pony, confiding in her what a wonderful lady she was all the while, and slipped the halter on. I thought the bit, a comfortable snaffle, was silver; it was etched with a small eagle and another insignia that I didn’t recognize. The bridle was beautiful leatherwork. He had loosened her girth and was hobbling her. I strapped the bridle onto the saddle and worked on my prayer some more. He stood up and looked at me, the mare started cropping the lush grass; I ducked my head to him, as I had no hat to doff respectfully.

“Take off your clothes Dmitri.”

“Yes Your Honor.” Boots, blouse, pants: my boots were my older brother’s and they were still a little large, I just had to kick them off; the drawstring on the throat of my blouse was already loose, nothing else to worry about and over the head it came; I’d already dropped the leather strap I used for a belt so my work trousers almost fell off. Didn’t take long and I stood naked before him thinking of Saint George. I had a small hand carved wooden cross around my neck on a leather thong and that was all I wore.

“Help me get undressed.”

“Yes Your Honor.”

This was a lot more complicated. To get his boots off, he sat down and lifted a booted leg up between my naked legs and we had to push and pull each boot off. I helped him stand up and we went to work getting his riding britches off: there were laces at the foot of his britches that allowed them to be neatly tucked into his boots; buttons secured his fly and kept them snug around his slender waist; these britches were obviously made just for him as they fit him beautifully. Then there was his blouse, which had a high collar, more buttons secured it, with even more buttons to allow him to open the throat and get it easily over his head; it had wide sleeves with yet more buttons on each cuff. I thought this blouse must be silk, it was certainly finer feeling than any material I’d ever handled before. I thought he must have more buttons on this one outfit than were owned by my entire family. I cannot help but admire his naked body: lithe, tanned, wiry. Like me he had hair only on his head. His staff of life was standing strong; the tip had fully emerged from beneath its sheath. Mine was a little more hesitant, not really sure, but hopeful.

“Can you swim Dmitri?”

“Yes Your Honor.”

Can you swim Dmitri?[7]

“Good. Let’s cool off.” He grabbed my hand and we entered the river. He swam beautifully, a stroke I’d never seen before; I paddled around, as a puppy would, just like all the other village boys. But I didn’t splash him or really play. He came back to the bank and splashed me and I tried to duck and act playful, but it was hard to be really playful when you were trying desperately to please another, but you barely knew the person you were trying to please. He stopped splashing me and we stood, knee deep in the water, and looked at each other.

He grabbed my hands, pulled me close, and kissed me on the lips. I kissed him back. “You are a beautiful boy Dmitri.”

I began to grow hard like him, our sexes nuzzled while we kissed. Mine was becoming firmer — more hopeful.

Oh Good Saint George, whatever do I say now? “And you are handsomer…er…than anyone Your Honor.”

He laughed, then smiled. “How old are you Dmitri?”

“I’m twelve Your Honor.”

“Excellent. I’m thirteen. I’m too young to be handsome, so we must both be beautiful. And I think we’re both still boys. Don’t you think?”

“Yes Your Honor.” That was what I was saying, but I was thinking, ‘whatever you say, I’m gonna be okay if all he wants is to fuck me’. Of course, I didn’t really know what that meant having nothing to base it on except the fumbling and rubbing the village boys sometimes engaged in at this very spot on the river. I mean, I knew about bulls and stallions, but there’s always a cow or a mare involved with that; here at the river there had only been boys doing it.

We went up on the beach and sat down on the sand. “Now, it’s about how I want you to address me. My name is Fjodor Gregorovich Berdyaev. Do you know who I am?”

Oh Sweet Jesus and Good Saint George. My worst fears came flooding back. He’s the Count’s only son! We were asked to pray for him in church every Sunday. I knew he was highborn when first I saw him, but I thought maybe he was a nephew or a cousin, or a guest, something like that. I guess I should have known from the start, he as much as told me that he owned me.[8] “Yes Your Honor.”

“Good, so from now on, you can call me ‘Your Honor’ or ‘Count’ only once a day, unless we are in public, or in the presence of someone who outranks me. After that, you are to call me Fjodor. Whenever we’re alone, you will address me with the familiar ‘ty’. Just as I do you. Understood?”

“Yes Your Honor.”

“What?”

“Uh, Yes Your er Fjodor Sir.” That wasn’t very good. “Yes please Fjodor I’ll try very hard to do that.”

He laughed and he kissed me again. He put his arms around me and we lay hugging on the warm sand. Daringly, I reached up and kissed him. “I’m practicing,” I whispered to him, “Fjodor. Fjodor. Fjodor. A gift from God is Fjodor. I thank God for all His gifts.” I rolled over and lay on top of him. I looked deep into the blue of his eyes and kissed him again. I loved the feel of him. I put my ear to his heart and listened to the life of him. This was the first time I’d lain naked with another boy, touching completely, from head to toe. If he wants to fuck me, if that means what I think it means; well, that will be just fine. We moved slowly against one another and I knew that great passion; this time shared with another and for the first time.

We swam again. As I started to dress him, he stopped me. “Tomorrow I’ll come for you and take you into my service. I wish you to wear this in token of me.” He removed the golden medallion of Saint Andrew he was wearing and placed it around my neck on its chain of gold. He kissed me on each cheek and on my lips.

I looked at him searchingly. ‘Do I dare?’ I thought as I knelt before him and pulled the wooden cross that I’d been wearing off and held it out in both hands before him. “Please Fjodor. It’s only beechwood. My Grandfather carved it for me when I was born. I am your man and it’s all I have to offer you.”

He pulled me standing. My God he was crying. “Put it around my neck Dmitri.” I did. Then I kissed his tears away.

I finished dressing him and leapt into my clothes. Mine were much faster and easier. We rode back to my cottage. My older sister was the only one there. Fjodor told her that he’d be back for me in the morning with his Steward. He hoped my parents would be there.

And, sure enough, next morning he came cantering up on a fine chestnut gelding. An older man followed him on a bay with the pretty little mare that took us swimming on a lead rope behind him. They dismounted and handed their reins to my younger brother. My Father is the village smith so all of his boys were trained to help riders without consciously thinking about it.

“Good day to you Mikhail Timofeyevich,” my Count greeted my Father; he clearly knew who we were without the need for an introduction.

“Good day to you Your Honor,” my Father replied bowing deeply as my Mother curtsied.

“Your son, Dmitri Mikhailovich has agreed, with your permission of course, to enter my service today. He will be first in my household. We will be at the country house most of the time and you will know when we are away. You and your family are welcome to visit him at any time.

“Of course, he’ll no longer be able to assist you in the smithy. Please accept this small token of my esteem.” The other man handed my father a small leather purse that clinked. “Well,” my Count continued, “there you have it.” He waved me to the pony.

I ran to my Mother and hugged and kissed her. “I’ll come and see you as soon as I’m settled.” I hugged and kissed my Father, “Thank you Father.” I ran to the pony and told her what a superior girl she was, mounted, and we started up the track to the big house.

That was how it all started. But now, I reminded myself, we were returning home from the war by railroad. We have gone almost completely around the world I thought. Not in one trip, of course, but our entire adventure began on the estate to which we were returning. We left going west. We were returning going west.

++++++++

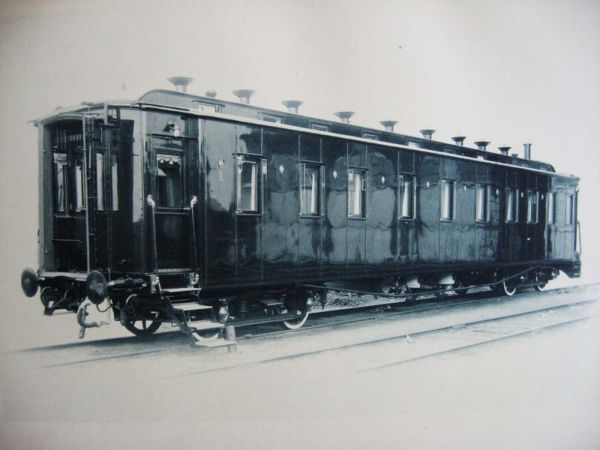

This is one of the very latest railroad cars

Fjodor was shifting about in his chair. “Will you get my crutches please Dimi; I need to use the water closet.” I’m brought back from being twelve and beginning to fall in love. Now I have a lover to care for.

“I’ve a chamber pot right here Fjodo, will that do?”

“No dear, it won’t.”

Serov led the way into the passageway and I followed so that no one could trip him up. We waited outside the water closet until he’d finished, and then escorted him back to our compartment. He could have done it by himself; there were hardly any first class passengers in our coach: but that would not have been correct.

We settled him on one of the benches and he announced that it was time for more of Serov’s lessons. When Serov first came aboard the poor old Brilliant he could neither read nor write. But he quickly caught my Count’s eye — mine too if the truth be known; and as soon as this lack became apparent, nothing would do but that Serov’s horizons must be expanded and he was taken beneath our wings, into our nest.

That was pretty much what had happened to me, only I was constantly learning from Fjodor as well as Monsieur, our tutor, and I could already read and write a little from the village school. Then there was Sebastopol and later Kronstadt. Now I know three languages, I can signal with flags and the signal lamp, I can shoot the sun, and I manage all of the accounts.

On this day, Serov and Fjodor were reading a book of Russian fables that Serov loved. Serov liked young Grand Dukes and Cossacks, flashing swords and snapping banners, handsome men and magic. Fjodor would read a paragraph, and then Serov would read a paragraph. Fjodor would correct any errors that Serov might make. Recently, Serov had begun to correct Fjodor. To be sure, Serov’s corrections were not about pronunciation or grammar, or any of that; he tended to think that Fjodor’s reading lacked drama; he wanted more excitement so he gave his reading great life. He never missed an opportunity for a sexual allusion if the characters were handsome and male. You could tell, though, that sometimes he was more interested in the drama than the written word; his telling of the story frequently went in directions, and might consider sexual issues, not always clear, indeed as often as not quite thoroughly hidden — that is if you relied solely on the written word.

Dinner was sumptuous, and the service was suitable to our station. It was served in our compartment because of Fjodor’s injury. The chief steward was obsequious and obnoxious. He thought his station in life was grand and sought to curry favor with Fjodor by talking only to Fjodor and ignoring Serov and me; Fjodor just ignored him completely thus compelling him to receive his orders from me. Serov would make faces at him when his back was turned and this caused one of his assistants to start giggling silently. I thought there might be hope for this assistant; he had coal black hair, eyes even bluer than Fjodor’s, and a ready smile that blew away the gloom cascading from the chief steward.

We dined lightly, lobster bisque, oysters on the half shell, fresh sturgeon, caviar, squab with wild rice and asparagus washed down with a bottle of white burgundy. We seldom had more than one bottle of wine with dinner. Fjodor thought that drunkenness was unbecoming and took the edge off sex. There was a fruit tart and coffee for dessert. Once the last course had been presented, the young steward that I liked remained in our compartment to care for us as we finished. I told him that we were pleased with his service, and gave him two roubles. An astronomical tip. I gave him my card with our address written on the back. “If you tire of the railroad, you might consider joining Count Berdyaev’s household. We’re just back from the war. As soon as you’ve cleared this away, we’d like a bottle of Veuve Clicquot Brut on ice and a nice bowl of fresh strawberries.”

“Yes, sir,” he replied, but his eyes as well as his smile were twinkling.

It was time to start preparing for sleep. This had become a lengthy process once Fjodor was well enough to fully participate. After our champagne arrived, Serov and I locked the compartment door, and we pulled the blinds and curtain over the windows that gave into the passageway. We made up the two lower berths. Then we stood before Fjodor. We hugged and kissed as we started to undress each other. Slowly, with lots of hugs, and kisses, we shed our uniforms; we stood naked and aroused before Fjodor. Then we went to each side of Fjodor, helped him out of his chair and settled him on one of the berths. Because he was convalescing, sex was limited. We began to undress him. Again, very slowly, with lots of lush kisses and fondling. When we had him stripped, we washed him gently with sponges dipped in warm water. We replaced his bandages, and carefully checked the wound as the surgeon instructed us, we ensured that he was healing properly. He really was starting to improve in all respects, he had his color back, pretty much; and he was hard and ready for passion long before we had him naked; but he would be on crutches for a long time before his stump would be ready for a wooden leg.

When we had him all clean; we stood before him, I wiped down Serov with a sponge, then he wiped me down. We stood before him, arm in arm, and waited for him to decide which of us he wanted to taste. Last night, it was Serov, so it’s no surprise when he points smiling to me, “Come Dimi,” he whispered.

That’s the signal, for our gentle passion to commence. Fjodor has always been very concerned about what he calls “evenses” when it came to sex, so all three of us must be replete.

Then we sat on the berth and sipped champagne and ate strawberries off each other. There is nothing quite like sipping champagne with the men you love to the gentle rhythm of the train. Particularly when you’re all naked in a first class compartment, passion expended, and the world will not intrude again until breakfast.

At length, we fussed Fjodor into some silk pajama tops and settled him in his berth. Fjodor doesn’t like to wear pajamas. But I was quietly insistent telling him that he can’t move as easily as he thinks he can and that he’s not going to catch pneumonia while Serov and I are here to love him. We made him take all of his medicines too.

“Tyrants,” he called us smiling. His smile always dazzles.

This was one of the very latest railroad cars, it had those new electric lights and they really are the greatest. We had them on the Brilliant too. Much better than oil lamps or candles, all you do is flip a switch and they’re off or on: no chimneys, no smoke, no matches, no footmen or maids bustling about. Serov and I spooned together in the other berth. Serov wiggled his bottom around until he had me snug between his cheeks. I reached over to lightly cradle his manhood with my hand. Sleep came quickly.

++++++++

The Order of St Vladimir 4th Class

As expected, His Honor Lieutenant Count Fjodor Gregorovich Berdyaev, late Captain of His Imperial Majesty’s destroyer Brilliant, with the Order of St Vladimir agleam on his chest, was having a cow because he was going to be riding home in a carriage rather than on horseback. His bluster was offset somewhat because he was standing on the station platform on crutches with the absence of his lower left leg obvious to all. But he was carrying on in splendid form for all of that. I’m not at all sure why he was doing this, but I was not surprised either. Partly, I suspect, it was because Serov had lately told him that his reading lacked drama. If there was one thing My Count, My Lieutenant, the Prince of my Heart loves, it would be drama. He knew very well that he was not going to be on horseback and he knew he was not going to win this argument. So he was really just playing to the crowd at the station. Drama! He was their Count’s son, after all, so these onlookers were a wonderful captive audience for his performance. He was clearly feeling very much better, almost his old self, so that made it all worthwhile so far as I was concerned.

Clearly, if he really wanted to ride, he could have compelled it. But he was addressing all of his orders and bombast to me, and he knows I’ll not be moved. At no time did he address any of these orders to someone who might feel that they must obey.

At length, he came to a breathing spot. I gestured for the phaeton, as it was a beautiful day. Serov stepped up to him and whispered, “Come, Angel Prince, let’s go home.”

He stared around the platform looking to the people; the people who had been pretending they’d heard nothing, as if to ask: ‘See how I, a hero! Am tyrannized?’ He clutched at his heart as if in pain. To look at him you’d think he was a prisoner going to the knout. He crutched over to the phaeton and climbed in with Serov and I right behind him. He looked a little surprised.

“Dears,” he whispered, “you don’t have to ride with me. You can ride horses if you’d like.”

“Thanks love,” I whispered back, “but we can’t do that. It’s you who taught us all about ‘evenses’.” He answered with his radiant smile and settled back on the cushions.

He did teach us about ‘evenses’ a concept which struck me as incredible when first he mentioned it. Once I thought about it, however, it was something that was evident in all of his actions. In bed, he wanted to be pleased, but he also wanted to please. As if the sex act were insufficient if it did not bring satisfaction to all involved.

In the same way, he did not want to win, if he could not do it on his own. For years, now, he had been losing our wrestling matches, but winning with the saber. Winning at chess, but he was always the loser at dominoes. He was better with the shotgun, I with the pistol; but then I never thought of shooting as a sport.

It frequently struck me that if all of the Motherland’s counts were as my Count, then Russia would rule the world.

“Home,” he told the coachman, and off we rolled. A phaeton, a carriage, two troikas, and ten spare horses, managed by two coachmen, two apprentice coachmen, four footmen, two grooms, a cook and his helper. This panoply was needed to take a Lieutenant, a Petty Officer and an Able Seaman home from the war. By now I had been with Fjodor long enough to know that this was as it should be.

I remembered that when Fjodor was sixteen he had come dashing up excited and all out of breath. He was waving a letter and he announced happily, “When I’m seventeen, we’ll be joining the Navy.” His smile, then as now, dazzled me. “And this summer we’re going to Sebastopol and we’re going to practice sailing. Papa has ordered a boat for us.”

I go all dreamy again.

‘Why?’ I asked myself. ‘Are things the way they are?’ I wasn’t asking myself the simple why. That was easy enough. Fjodo and I had met quite by accident and quickly fallen in love. Then, when I met Fjodo’s father, whom I always called the ‘Old Count,’ everything seemed to follow logically. I passed muster as a loyal retainer.

I’d been exercising Tiglath and Pileser, our matched Arab geldings, and had just stepped out of the stable when I met the ‘Old Count’ for the first time. He was standing as if he had been waiting for me. That was absurd of course; he’d never wait for a peasant. He’d been looking right at me when I came through the door. I stopped and bowed formally to him as Fjodo had taught me. He was a beautiful man: imperially slim, immaculately attired in a silver-gray uniform with only one decoration glittering around his neck, golden epaulettes, straight leg trousers with golden stripes down the outside seams; he was blond, too, with little sparkles of silver at his temples, and his eyes shimmered blue just as his son’s did. I could not help but think that, when we were old, Fjodo would still be beautiful.

He quizzed me at length. “You’re Dmitri Mikhailovich are you not?”

“Yes, your High Excellency Colonel-General Count Berdyaev, I am.”

He went on from there to cover a host of topics, from the length of my hair; to how I felt about being in Fjodor’s service; and what I thought about this estate including discussion of some crop management issues and livestock breeding programs.

“So. What do you think of Fjodor Gregorovich, Dmitri Mikhailovich?”

Well. There it is. How in the world can you answer that?

I looked straight into the Old Count’s eyes and I sense no animosity, no guile, just genuine concern. I’d been raised a peasant, son of the village smith, so of course I knew my manners when in the presence of the highborn; but I’d also been the constant companion of Fjodor for several years now, I was loved; I was steeped in the stories of Tsars and Princes, noble deeds and spear points gleaming; of courage and faith and gallantry; of loyalty and service. I looked into the eyes of the father of my beloved and knew that this was not the time for peasant servility.

I went down on one knee, but continued to look up at the Old Count, straight into his eyes. I knew, somehow, that I must. “I am Fjodor’s man. Of his estate. He is my Prince to whose service I was born. God and Good Saint George willing, I’ll be with him for so long as I breathe.”

The Old Count looked at me for the longest time and then gestured for me to stand up. “What do you call my son?” The examination was not yet over it would seem.

“’Your Honor’, Your High Excellency. I call him ‘Your Honor’ as is seemly.”

A broad smile stretched across the Old Count’s face and he chuckled gently. “Horse shit!” He laughed deeply. “Let me see if I’ve got it right. The two of you gallop up to the river bank, tear off your clothes, and then you say: ‘Last one in is a fresh horse turd, Your Honor Count Fjodor Gregorovich Berdyaev, Sir.’” He laughed deeply for a few moments and then looked the question at me.

I could feel my face burn red with embarrassment. I looked at the ground, I mumbled, “I get to call him ‘Your Honor’ once a day. Most of the time I call him ‘Fjodo’; I call him ‘Fjodor’ if I really need to get his attention. I call him ‘Fjodor Gregorovich’ if he’s in troub…er, about to make a mistake, or, I mean, well, something. I always call him’Your Honor’ in public, as is proper.” I had finished in a rush.

And that was that. The Old Count smiled and nodded. I was acknowledged as Fjodor’s man and had been with him ever since.

We stopped to camp for the night along the river. The same river that Fjodo and I had swum in that first time. Just a day’s ride further up the river from our original spot. Serov and the young footman Genrikh had taken Fjodor down to the river where they stripped for him so that he could enjoy their beauty. Then they undressed Fjodor and carried him, one on either side, down and into the river where they splashed and played gently as they were joined by other members of our little troop.

They splashed and played gently[9]

Serov and Genrikh delight the eye. Genrikh was just starting at the Great House when we had left for the war. Then he was rather awkward and gangly, a young teen full of promise and young enthusiasm. He had matured beautifully, a ready smile, dark blond hair, deep brown eyes and a certain sexy swagger that he carried off well whether he was dressed, or playfully nude.

I’d known Serov since first he came aboard the Brilliant back in Kronstadt before the war began. His beauty is lush and rich; his hair is a brown so deep as to seem black unless you catch him in the sunshine, then his hair flashes with dark highlights as it cascades in waves over his head; his eyes are hazel; and there’s a scatter of moles that attract the eye favorably to a muscular but smoothly boyish torso; he’s beautiful to behold and his soul is beautiful to know.

We shared a pleasant camp and a delightful meal. Some gentle music from the balalaikas of the servants, and then the music of the night.

Mid-afternoon of the next day we arrived at home. We had slept late in the glory of the morning. Breakfast was late. We did not stop for lunch.

We were home again, and I continued to wonder and question God and the Saints. What had we done? Why had we done it? What about our friends and shipmates who had accompanied us and could never return? Were we better off for our actions? If Serov, in the full glory of his young manhood, would wake up screaming in the night if he tried to sleep alone: well, could that be a good thing?

We were, home again, with three small medals, a torn and stained flag, Fjodor’s naval dirk, our lives, and our memories. But there was more. There was that question. The one that was beginning to haunt me. A question for which there seemed to be no reasonable answer; I would simply ask ‘why’ and the answer fled in a thousand directions at once. Would the sun ever really shine again? For me?

Saint George Cross, 4th Class

I looked off across our estate into the expanse and tears came.

[1] Here is the Izumrud at anchor and she has ‘dressed ship’. At the battle she would have had large ensigns flying from each mast, but the signal flags would be used to signal, not to ‘dress’.

[2] Imperial Russia did not use the ‘yard’ as a measurement; neither did it use the metric system, but it seemed an unnecessary distraction to attempt to use the original Russian measurements. Since a yard is an ‘imperial’ measurement it seemed more appropriate than the thoroughly pedestrian metric system.

[3] It should be noted that the Japanese military had not as yet been infected by the contempt they would show to prisoners of war in later years. The Russian commander, Admiral Rozhestvensky was seriously wounded in the battle, but he was hospitalized and healed in a Japanese hospital as were others. He was even visited by Admiral Togo Heihachiro when in hospital. There are a number of accounts of the adventures of the fleet he commanded readily available; Pleshakov’s The Tsar’s Last Armada is contemporary and well written. It also provided the spark for this story. Years ago, Richard Hough’s The Fleet that Had to Die was serialized in The New Yorker. This is a great sea story that continues to fascinate.

[4] Books have been written about the complexities of the different orders of different nations. There is a lot of confusion on the subject, particularly if Hollywood is involved. Suffice it to say that the “classes” of these two awards do not mean their value is in any way diminished, they are just the first awards of the orders. The next classes would represent subsequent awards of the same order awarded for similar deeds. The Order of St Vladimir could be, and was, awarded for service to the sovereign other than military. Until 1900 the award of the 4th Class conferred nobility upon the recipient. The Cross of St George was originally for enlisted men, but junior officers were later included. These medals might be very roughly comparable to the US Silver Star or the UK Military Cross.

[5] In real life, this is the destroyer Brinyi in 1901.

[6] Extreme deference was required of the lower classes to the aristocracy. I use this form of address to indicate that deference.

[7] Swimmers by Joaquin Sorolla y Bastida

[8] Fjodor is accorded the title ‘count’ as an honorific. He depends on his father for an allowance or other properties. He will inherit all the estates in the usual manner. It was not unusual for Russian noble sons to have rank but no authority of any kind. The Grand Dukes, as children, would be a case in point.

[9] Boys Bathing by Max Liebermann, 1896.