Monk

by Joe Casey

joe_casey_writer-mail@yahoo.com

“Lou Whitney!” Scotty repeated, eyeing me with a disbelieving stare.

I shrugged. “No idea. Never heard of her.” Not entirely true, but good enough for this exercise.

The stare intensified. “Seriously? Monkeyshines? The Princess Wore Scarlet? Gunslingers? The Cartwright Sisters?”

“No.” I grinned. “That’s a lot of movies. How old did you say she was?”

“Cripes, Monk—you need to get out more. She’s only the most gorgeous doll in the movies right now.”

“Good for her?” At that, Scotty rolled his eyes; apparently everybody knew about this but me. Curiosity got the better of me. “So, why is she here on the ship?”

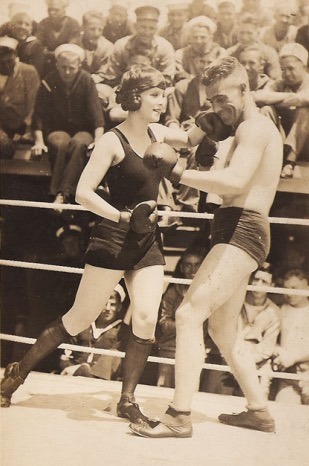

Gradually, I got the story out of Scotty, not one for finely polished rhetoric, although he made up for that in other ways. Lou Whitney was apparently here to shoot some publicity photographs for an upcoming movie—The Heiress and the Hero, presumably involving either sailors or boxing, perhaps both—and wanted to be seen “fighting” with some of the boys while the ship was docked in Brooklyn. It didn’t make much sense to me; why didn’t they just shoot some pictures at the studio instead of dragging everybody down to the Brooklyn Navy Yard?

“It’s what she wanted,” Scotty explained. “She wanted some of the boys to have fun.”

“And put bodies in seats when the thing comes out,” I retorted.

Scotty shook his head, disgusted with me. “Cripes, Monk—ya gotta be a critic about everything?”

•

Well, no, but …

Actually, I was just busting Scotty’s chops, an activity I found always rewarding. I knew who this Lou Whitney was, although I hadn’t seen any of her movies. I don’t go to movies, can’t stand them; the idea of sitting alone in a dark room watching flickering shadows on a screen seemed somewhat … gothic and strange, and more than a little pathetic.

A lot of the boys went to the movies when we were in port, mostly because it was a good, cheap way to kill a couple of hours of free time until they could end up in the saloons. Scotty had asked me to go with him on several occasions; I’d always demurred, claiming ship work or some other excuse.

I eventually forgot about it and settled in my bunk with a book; we were in dock for repairs and upgrades, and we all had some time to ourselves at the moment … apparently as part of whatever the hell was going on upstairs. Ordinarily, we’d all be busy; idle hands and the devil’s playground and all that.

But curiosity, again.

•

It was easy to spot the crowd on deck; I shouldered my way past some of the boys and found myself fetched up against Scotty and his buddies Nick and Pete. Scotty glanced at me and turned back again, smiling slyly.

“Couldn’t resist, could you?”

“No,” I smiled. “It was either this or Kierkegaard.”

Scotty rolled his eyes. “Okay, Monk.” He turned back to watch the growing activity. I watched Scotty out of the corner of my eye, delighting in his delight, in seeing excitement on his handsome Irish face. I wondered how many people besides me knew Scotty’s real name: Sean Patrick O’Malley. He’d quickly become Scotty when he’d come aboard, christened that by men who had no clear idea of geography, apparently. He was a Southie from just up the coast, in Boston. I’d been to his home, met his parents, was delighted that a bit of the brogue could still be heard in his speech.

Somehow, already, a square of bleachers had been erected—probably by the very people watching all the commotion—around a regulation boxing ring, which was empty at the moment. I assumed that this Lou Whitney was still backstage getting ready. The bleachers were full of men, talking amongst themselves; in the background, a medley of popular jazz tunes played through a loudspeaker.

“You got any idea who she’s going to be boxing, Scotty?”

“Nah. Somebody said she’s gonna pick somebody out of the all the guys, anybody’s interested.”

“You gonna do it, Scotty?”

He smiled, slyly. “Maybe. Chance to meet a dame like Lou Whitney? Why not?” He nudged Nick, looked back at me. “You gonna do it, Monk? You box, right?”

I did, sometimes, when the mood struck me, when the only way to release my inner devils was to throw a punch at somebody’s face. But … “I don’t know. She’s not gonna pick a joker like me.”

Scotty shrugged. “You say so. You’re a better fighter than most of us.” He grinned. “And you don’t look half so bad. In the right light.”

“I don’t know …”

“Even if you are an ugly mook.”

I chuckled. “Thanks, Scotty.”

Just then, a guy in a suit came out from behind a curtained-off area. He walked over to a microphone as the crowd started applauding … probably bored from sitting around waiting for all the fun to start. His voice, when he spoke, was honey-smooth and practiced; I pegged him as some public relations guy for the studio. He introduced himself as Chet Bingham. Basically, he confirmed—in better language—what Scotty had said, and more than a few guys started streaming down from the stands for a chance to meet the estimable Miss Whitney.

Eventually, all the candidates—including Scotty, Nick and Pete—were lined up along the perimeter of the boxing ring. When nobody else seemed to be interested, Bingham looked up into the crowd. “Anybody else, before we start?” he asked.

Nobody else came forward. Bingham stepped away from the microphone and beckoned to two other sharply-dressed men to join him; the three of them started walking around the perimeter, looking at the boys waiting eagerly for their chance. Every so often the trio would stop and confer amongst themselves, then offer a fellow a hand, dragging him up onto the stage to the applause and gentle derision of his mates.

They slowly worked their way around us. I stood behind Scotty, looking away, assuming that I wasn’t in the scrum. I applauded as they whispered amongst themselves—as much for effect as anything—and then offered Scotty his chance and hauled him onto the raised floor of the ring. But, then …

“Hey, you!”

I glanced over, thinking he’d meant Nick or Pete, but one of the two assistants was staring directly at me. He’d been talking to me. Stupidly, I pointed to myself, eyebrows raised with the obvious question. He nodded. I stepped forward.

“You interested?”

“I … well, I don’t … I’m not sure.”

He stared at me, eyes squinting. Something about him …

He smiled. “Doesn’t hurt. Wait a minute.”

He turned to the other two and they repeated the same manic huddle; the other two men risked glances at me before turning back. Another minute of fierce whispering, and then they broke apart. The first man—the man who’d addressed the audience—came over and held out his hand. Nervously, I took it, and allowed myself to be dragged up with the others.

•

A baker’s dozen of would-be sparring partners for Miss Whitney were gathered there by the time the circus was done; they dragged all of us back behind the scrim of black curtain from which the first man had appeared. I looked at all the boys who’d been picked; to a man, they were all athletic and muscular, tall, handsome.

Which made me wonder what I was doing there.

I made my way over to Scotty, noticed that he had a bundle of something in his hands. I looked around; all the guys had similar bundles. I nudged him. “What’s that?” I whispered.

He looked at me; I gestured at the bundle. He unfolded it to reveal a pair of grey-black, form-fitting trunks and a well-used jock. I had a similar Navy-issued outfit in my locker, shoved under my berth; it was what we used when we boxed or did anything remotely athletic. I looked down at Scotty; he was already wearing his boxing shoes and a pair of white cotton stockings, which completed our minimal outfit.

Maybe I should have read the announcement.

“Was I supposed to …” I whispered.

“Yes,” he whispered, shaking his head.

“Shit,” I muttered, although it didn’t really matter; they weren’t going to pick me, anyway. I turned to go.

The assistant—genially handsome in a polished kind of way—noticed me. “Where are you going? Don’t you want to—”

“I forgot my uniform.”

“I—oh.” He frowned. “Well, wait up. We might be able to cobble something together for you.”

I opened my mouth again, but the smooth-talker told us to go into a curtained-off dressing area and change into our uniforms. I dutifully followed, and the assistant, Alan, followed me in. Inside, he turned to another man.

“You got anything to fit him?” he asked, jerking a thumb back at me.

This chap—short, thin, wasp-waisted—looked at me. Looked harder. A small smile wrinkled his pursed lips. “You forgot.”

I nodded. “Sorry. I hadn’t planned on …”

“No problem.” He turned and rummaged through a pile of clothing, surfaced with a pair of dark-grey trunks that were close enough to what we usually wore. No jock, but I probably wouldn’t need it if all I had to do was beat an aspiring young ingenue to a pulp.

“Shoe size?”

“Er—twelve.”

“Big boy, I see.” He smirked and laughed at his own joke and rummaged through another pile—shoes, this time—came up with a pair and handed them to me, then pointed to the dressing room.

“In there.”

“Thanks.”

•

Inside the room were twelve other guys in various states of undress. I joined them, quietly stripping off and slipping the trunks on. They weren’t quite right, both too short and too tight. The bottom curve of my … well, bottom, was exposed. I sighed and put on the socks and shoes, then joined the rest of the now-dressed men back outside.

The wardrobe guy, Stuart, noticed me and nodded his approval. I seemed to have passed.

Bingham ushered us back out and into the ring to scattered applause and good-natured catcalls. Some of the guys started clowning, drawing even more of a response from the men in the bleachers, who were clearly enjoying themselves. He let it go on for a few more minutes until Alan came out and nodded, then set about arranging us in a rough single-file line.

Miss Whitney must have finally decided to present herself to us. About damned time, I thought; I was already regretting the decision to take part in this, parading around almost naked in a pair of trunks that were sized for a sixteen-year-old. Kierkegaard was looking better and better.

Bingham stepped up to the microphone and turned it on with a small squeak of feedback and static. He started on a short introduction, telling the crowd about the upcoming movie, the stars in it, the studio behind it, the theaters it would be shown in … to me, it seemed like he was vamping for time. Finally, at a gesture from Alan that everything backstage was tickety-boo, he got down to business.

“Gentlemen—and I use that term loosely—” he said, to scattered laughter and catcalls; he had them hooked already, but they were starved for diversion, “thank you for waiting patiently. You have before you a bevy of beautiful babes to enjoy—and, oh, yeah, Lou will be out shortly, too.” More laugher; a few of the boys essayed pin-up girl poses. Bingham opened his mouth to say something else, but then the curtain behind him parted and a young woman stepped out.

Lou.

She was pretty, I had to admit; easy to see why she’d made it into the top ranks of stardom. Fresh-faced, with a girl-next-door air about her, somebody’d you’d have been friends with since you’d both been kids and then found yourself falling in love with at some point.

The men went crazy; Lou ate it up, walking around, posing and flexing like a boxer while the men whistled and applauded. She was dressed in the female version of what we wore: a black singlet and shorts, stockings and boots, more revealing than might have been good for her, given the crowd arrayed before her, but she exuded a strange and beguiling mix of sweetness mixed with a certain sensuality. When she was done parading, she walked over to Bingham and the microphone.

Bingham smiled and ceded control of the microphone to her; she bent it down to her height. “Thank you, Chet.” She smiled, arched an eyebrow. “Did you find anyone brave enough to go one-on-one with me?” Hoots and catcalls from the audience.

“I don’t know, Lou. Not much here to work with.”

She looked us over, then back at Bingham. “This is it?”

“Afraid so, Lou.”

She walked away from the microphone and over to the start of the line. She went slowly down, evaluating each man, squeezing biceps, doing thumbs-up or thumbs-down, depending. The crowd applauded or booed as she clowned. Even I had to chuckle as she worked her way through us men.

She got to Scotty and pretended to swoon; I had to admit, Scotty was the best-looking of all the men standing in line. The boys went crazy as she studied him, certain that he would be her choice.

Then she saw me, and went quiet. She walked over to me. “Hmm,” she murmured. “Look what the cat dragged in.”

“There’s been some mistake,” I answered. “This isn’t the line for Schrafft’s?”

“Not by a long shot, bucko.” She launched into her routine; I allowed myself to be poked and prodded by this slip of a girl. I had to admit that I enjoyed it; Lou was easy on the eyes and all of the laughter and joking from the audience was friendly enough. Finally, she turned to Bingham and the audience. “Gotta admit, Chet—slim pickings. But I think this one’ll do just fine. I think he’s a pushover.”

Looked like I was it.

•

The cameras clicked and whirred as we pretended to spar, throwing light blows at each other, dancing and bobbing around in a strange kind of foxtrot … and, I had to admit, Lou was pretty light on her feet.

“You’re being an awfully good sport about this,” she murmured, as she struck a glancing blow across my jaw. In the background, cameras clicked and whirred.

I grinned. “Not every day I get to beat up a girl.”

“Oh? Hobby of yours? Years of practice?” She grinned back.

“Well … had to give it up for Lent.”

“It’s August, sailor boy.”

“I didn’t go to church all that much, anyway. Couldn’t make it through the confessional without the priest fainting.”

“I’d have thought you were of another persuasion, by the … uh … look of you,” she retorted. When I understood what she’d meant, I blushed. There was nothing but me underneath the trunks … which fact was too patently obvious.

“Tut, tut,” I managed. “Nice girls don’t talk that way.”

“What did I say?” she protested. “Anyway, I think you’ll find that I’m not that nice a girl.”

Bingham leaned in, at that point. “Another minute, Lou, and then we’ll be done.”

Thank God, I thought.

To my surprise, Lou frowned. “So soon?”

“Yeah,” Bingham answered. “Sun’s at the wrong angle.”

Lou blew out a breath. “Fine. Tired, anyway. Being brutalized is horrible.”

I chuckled. “You’re the one who picked me.”

“I’m beginning to have second thoughts.”

“You know, I really don’t beat up girls, as a rule. At least, not the nice ones.”

She stuck her tongue out at me. Damn, she was charming.

•

Later that afternoon, before mess, Scotty poked his head into my berth, dressed in nothing but a towel wrapped low around his hips, skin still glistening from the shower. “What did you say to her?”

“To whom?”

“To whom?” he echoed. “To Lou Whitney, that’s whom.”

“Nothing.” I scrunched my face up, thinking. “Well … I might have mentioned that you preferred the company of farm animals to that of humans. Other than that, not much. Why?”

He sat on my bunk. The towel did some interesting unfolding things around his thighs as he got comfortable. The whole of his right leg was bared, up to the knot he’d tied in the towel, at his slender waist. One sneeze, I thought … I glanced and looked away, quickly. “She’s inviting all of us—even you, you lunkhead—to some swanky club up in Midtown. The … Domino Room, I think she said?”

I’d heard of it. Invitation only, so I’d heard, and chock full of Broadway types mixing with young turks living on what was left of their fathers’ inheritances. “Have fun,” I answered.

“Jesus, Monk, c’mon! Loosen up a bit! Free booze? Movie stars? Lou Whitney?”

“I’ll pass.”

“But she asked for you! Specifically! You gotta go! You’re the one she picked!”

I didn’t gotta do anything, I thought. But … “Okay. When?”

“An hour. You’re supposed to wear your dress uniform.”

•

We arrived at the club shortly after eight in the evening; a fleet of shining black Cadillac V-16 limousines had pulled up alongside the ship and divided us up into groups of three and four to usher us into Manhattan.

We looked pretty impressive, I had to say, decked out as we were. We seldom got to wear dress uniforms; as it was, some of the younger boys had to be reminded how to wear them. Heads turned as we entered the club and the room went very quiet as the crowd took us in, wondering—as I would have done, were I in their shoes—what the hell a bunch of Navy was doing in a place like this. Luckily, Lou showed up quickly and explained what was going on; the boys dispersed quickly through the crowd, heading, no doubt, straight to the bar.

Lou, of course, looked like a million bucks, in a beaded peacock-blue gown that sounded like rainfall when she walked … a far cry from the uniformed brawler I’d “contended” with on the deck of the ship this afternoon. She was easily the most beautiful girl in the room … and the room was full of them, actresses, probably, as Lou herself was, along with a handful of heiresses and models, all of them splendidly turned out. There was a handful of men as well, all of them immaculate in tuxedos. Some part of me noticed that while most of the men were in the company of women, some few of them seemed to be paired off by themselves, talking quietly—even intimately—over cocktails.

The club itself was elegant, easily the swankiest place I’d ever seen or been in, all black lacquer and mirrors as befit its name, with black velvet and leather club chairs trimmed in white piping scattered throughout the room, punctuated with black glass and chrome tables.

Lou caught sight of me and made her way over. “Hello, you,” she said, smiling. “You decided to come, after all. I was worried.”

I smiled back. “How could I resist? You, by the way, look wonderful.”

She beamed and turned a quick pirouette; the beads tinkled and pattered in response. “Thank you. I do, don’t I? So do you. By the way.”

“Don’t expect me to twirl around.”

“Spoilsport. You’re supposed to be athletic.”

“Only when I’m fighting. Other than that … two left feet.”

She looked down at my empty hands. “Do you have a drink, yet? Come on, you need a drink.” She took me by the hand and dragged me to the bar, where I disappointed both her and the bartender when I ordered a pint of beer.

We started towards a pair of empty seats when she stopped. “Oh! There’s Martha Dunning! I should … but …” She turned back to me, confused.

I chuckled. “Go ahead. I can wait.”

She eased away towards a tall, graceful blonde in a maroon dress that looked painted on her twig-thin body. “Thanks! But—don’t go away!”

I sat in one of the chairs and sipped the beer, which was far better than my usual swill. The chair was comfortable; I could easily have fallen asleep in it. I waited for Lou to reappear, but at some point I lost her in the crowd. A couple I didn’t know looked anxiously around for a place to sit, so I gallantly surrendered my chair and went back to the bar.

“Is there an outside patio in this place?” I asked.

“Yes, sir.” He jerked his head towards a passageway. “Go through there, then up.”

“Thanks.” I made my way to the hallway and up, emerging onto a pleasant, landscaped rooftop terrace surrounded by towers that I guessed might be Rockefeller Center. Other couples were up here, as well; I walked over to the parapet and glanced down to the crowded street below. I looked at Manhattan every night from the deck of the ship when we were in port, delighting in the majestic rise and fall of its skyline; being here in the middle of it was both strange and wonderful.

•

“Thought I’d find you here, Mr. Monk.” Lou eased herself into a chair opposite me; far below, the noise of the streets drifted up. A faint breeze, welcome and cool, drifted across the terrace.

“Sorry. Needed a bit of fresh air.”

She fanned herself with the palm of a hand. “I know what you mean. Stuffy in there.” She looked at me through narrowed eyes. “Having fun?”

I saluted her with what was left of my beer. “Of course. Thank you for doing this.”

She toasted me with what looked like a gin and tonic. “It’s the least I could do. You earned it.”

“Well, I don’t know about that …”

“Well, I do. Thank you for being such a good sport, again. I hope it wasn’t too painful.”

“No, no … I enjoyed it. We all did. It means a lot, to be here in this place.”

She looked around; a few other couples were still out here with us, some of them trying with little success to see what we were up to without being too obvious. “It is nice, isn’t it? I tend to take it for granted. I know that I shouldn’t. Oh—I’m sorry I abandoned you earlier. Not very polite, but …”

I shrugged. “How are the boys doing? Behaving themselves?”

She nodded her head. “For the most part. I’m sure Emile will let me know if they get too rowdy.”

“Emile?”

“The owner.”

“Well … just knock a few heads together if you need to.”

We fell silent; I nursed my beer, which was now warm. Lou sipped delicately at her cocktail, looked idly around. I was probably boring her to tears and she was trying to find a nice way to rid herself of me. I couldn’t blame her. She turned her attention back to me. “How long have you been in the Navy, Mr. Monk?”

The Mr. Monk was strange; I assumed she was being clever. I turned my face up to the night sky, thinking. “Well … let me see … five—no, six— years.”

“Long time. You like it?”

“I do. It’s what I needed, I think. Where I needed to be.”

“Interesting. Why is that?”

I smiled, shook my head. “Long story. Boring. No plot.”

She grinned. “I like long, boring stories with no plots. Certainly you’ve seen some of my early movies.”

I chuckled. “Actually, I haven’t.”

She feigned surprise. “Well! If I’d known that, I wouldn’t have picked you.”

“I gave you a chance to back out. You should have picked Scotty. He’s in love with you.”

“I almost did, you ingrate. Scotty’s a doll.” She giggled. “And Scotty may be in love, but it certainly isn’t with me.”

“I wouldn’t be too sure of that. You might want to watch yourself.”

“Oh, please. If anything, Scotty’s in love with the girl in the movies.”

“And that’s not you?”

“Oh, no. Not by a long shot.” She frowned as she said that, looked away.

The frown surprised me. “I’m sorry. I didn’t mean to be rude.”

She turned back, smiling again. “You could never be rude, Mr. Monk.” She gestured to a waiter lurking in the shadows, ordered another beer for me before I could refuse, and another gin and tonic for herself. She polished off the last of the one she had.

“God,” she started. “I’m so glad Prohibition is done with.”

I chuckled. “Been drinking long, have we? Since we were six?”

“Hah! Well, Daddy always was a little indulgent. He insisted that we get plenty of fruit and grain. I just prefer mine in a slightly altered form.” She glanced at me. “Must have been horrible for you boys. What did you do?”

“Made our own, sometimes, although there’d be hell to pay if we got caught. Plus, we have these things called ‘ships’. You may have heard of them. They can sail to other countries, with other customs.”

She stuck her tongue out at me again. “Clever boy.”

“I try. Not always very well.”

“So. Back to my original question. I want to hear your long, boring, plotless story. What were you escaping?”

I swallowed, a bit nervous, hoped that she couldn’t see it, but she seemed to notice everything. I shrugged. “Oh, just boring life on the farm.”

Her mouth quirked. “Not a bad place to be from. What was so horrible about it?”

“Animals. Plants. Acres of empty prairie. Mindless anonymity and a horrifying banality.”

She smiled. “Oh. That.” I chuckled. “So, the Navy, then?” she continued. “Why?”

“A chance to see the world. New places, new people.”

“Stuck in the Brooklyn Navy Yard.”

“Well … it’s better than my childhood. And we’re here for only a short while.”

“Have you, then? Seen the world? New places, new people?”

I thought about it. “For the most part. I’ve enjoyed it.”

“It must be hard work.”

I nodded. “It can be. I don’t mind it. It keeps me in shape.”

“It certainly does.” The waiter returned with our drinks; she took hers and held it up. I did the same.

“Cheers,” she offered.

“Cheers,” I replied.

“Here’s to a good long life in the Navy, Mr. Monk. May your ship never sink.”

“And to a good, long life in the theatre, Miss Whitney. May you break many legs.”

She chuckled.

“Incidentally,” I continued “why do you keep calling me Mr. Monk?”

She set down her gin, frowning. “But … I mean … well, isn’t that your name?”

I shook my head. “Nickname, maybe. My real name is Dan Keller.”

She rolled her eyes, obviously annoyed with herself. “I’m so sorry. I heard the boys calling you that and I thought it was your given name.”

“It’s alright. I’ll answer to Mr. Monk. Usually, it’s just Monk.”

“You should have told me. I’m so sorry.”

“My mistake.”

“Why Monk? Does it mean anything?”

“I think it refers to my unfortunate physiognomy. I’ve been told that I rather resemble a baboon on most days. The better ones.”

She arched one eyebrow at me. “Really? Who told you that? I beg to differ. You’re a very good-looking man, Monk. Mr. Keller. Dan.”

“Well …”

“Why do you think I chose you?”

“Pity?”

She pulled a puckish face. “Well, of course … at first. But you were … well, the best of a bad lot.”

I laughed. “I’ll tell Scotty you said that.”

“So, again. Why Monk?”

I shrugged. “I don’t know. I guess I keep to myself a lot. I don’t … well, I don’t do things like this, as a rule.”

“Why?”

I shrugged again. “I don’t know. It just wouldn’t seem …”

“Prudent?” At that, I nodded. She continued. “You’re young, you’re handsome, you’re … well, as far as I know, you’re unattached … and I assume that all your various bits and pieces work as advertised?” She looked the question at me; I nodded again. “So—sow some wild oats, Monkey Monk! Have fun while you can!”

“I do have fun.”

“Reading Kierkegaard? I’d rather have my fingernails pulled out.”

“You’ve been talking to Scotty, I see.”

She smiled smugly. “A bit. He is rather engaging. One of his many fine qualities.”

“That’s one word for him. I can think of others.”

“I’m sure you can … probably a few you’d rather I not hear. But, really … do you ever just … cut loose, sometimes?”

I shook my head. “No. Not really. Dangerous.”

“Boring.”

“Predictability isn’t a bad thing.”

“One’s life should never be predictable, Monk.”

“It’s safer, maybe.”

“Oh, to hell with safe! You’d be surprised how far you can push things and have them snap back. At least while you’re young.”

“Perhaps.” I thought back to a certain fall some years ago, in college.

Lou studied me. “What are you thinking?”

I tried my best to look inscrutable. “Nothing.”

She returned my inscrutability with a simpering smile, trumped it with a look of her own. She sipped her gin; I sipped my beer. Part of me was actually enjoying this.

“Your nickname should be ‘Cat’. As in ‘Cheshire.’”

I grinned wildly, eyes flaring wide.

She laughed. “‘I’d like to ask you an impertinent question,’ stated our plucky young heroine.”

I grunted out a laugh. “Ask away.”

“You’re not going to like it, I think.”

“Try me?”

She pursed her mouth, considering. I steeled myself.

“Who was he?” she finally volunteered.

“I … who was who?”

“The boy you loved.”

•

Timothy.

Shy, even more so than I, to the point of painfulness. Halting in speech, diffident, unsure of himself, always there on the periphery of things, never in the middle.

Two peas in a pod, us.

His beauty, under the thick spectacles, under the thatchy tow of an unfortunate haircut, under the ill-fitting and drab clothing he habitually wore, was simple and austere, that of a saint, perhaps, or some prophet alone and adrift in the desert. Most people wouldn’t have bothered. I bothered.

I couldn’t even recall, now, how we’d met. A shared class, or some other commonplace thing, perhaps seeing each other on campus one day, eyes locking to eyes, that shared glance that revealed so much while concealing everything.

Coffee next, each of us huddled over a steaming cup at a café far from campus, a rough, time-worn diner actually, nothing remotely café-like about it, surrounded by workers and tradesmen and careworn housewives with plaintive children in tow. But we were safe, or thought we were, from curiosity and prying eyes and wagging tongues. We imagined ourselves in Paris.

Each word spoken revealed another layer; he was the son of academics, whose love of knowledge far outpaced any love for their son, the shared product of their one and only fruitful union before they’d separated. He floundered daily with life, forever confounded by it, sent away to boarding schools, left in the haphazard care of governesses, now cast free upon the world, cosseted by university life, at least for now, until kicked rudely out at some point because that was the way things were done.

He and I shared little but this one thing, this dark and voluptuous thing that circled just under our skins and evoked such thoughts as no man should ever have about his fellow man.

We were each in our last year of college, he immersed in his poetry and language, in Greek and Latin, in the oaken reveries of Elizabethan English and tongues far older. I, more practical, an engineer, the first in my family ever to attend college, careful to make no missteps, to bring no shame to my family, to show them that I could do this thing and become something greater than what they had been and were still, always on tenterhooks that I would be found out, revealed for the monster that I thought myself to be.

And now, Timothy, the wrench gumming up the works, the irksome stone in my boot, the unscratchable itch in the base of my brain and the base of my manhood.

Gradually, we fell in love.

In college, if nowhere else, one was granted a certain license, a certain pattern of behavior. Friendships were encouraged between young men, if only because such friendships led to greater things, to good jobs and promotions and other things that our society deemed noble and worthy of pursuing. Eventually, one sorted things out and found a girl and married and had children and a foursquare[1] in the suburbs and a maid.

We styled our friendship on those friendships, at least on the surface, thinking that we had everyone fooled, that our camaraderie was the same as those we saw between other young men, some open and guileless thing we had as each sought to determine his place in things, in life.

But, underneath, temptation. Oh, what temptation! How could one not yield to it?

And, thus, we did, one day, one bright and golden October day that will forever be graven into my memory. While the world performed its clockwork dance outside our window, we stopped time, if only briefly.

Temptation was a third person, that day, in that room, sitting between us, negotiating each twist and turn, brokering our desire for each other until we lay there, on the bed, side by side, attired in nothing but that which God had dressed us in at our birth. We tatted ourselves together like Battenberg lace, knotting and knotting until we were nearly one, limb against limb, lip against lip, breath mingling in the still air of our room, silent in our shared passion lest we be found out.

Precious few such days followed, each a prized jewel stolen from this cruel and wanton passion; winter was transformed from its grey and frozen humdrummery into a crystalline and magical realm, the cramped and drafty room in which we loved each other became something befitting royalty. We were that royalty, princes in our private sovereignty; we communicated by thought across long distances, or imagined that we did. Whenever we saw each other—on the streets, walking across campus, passing each other in a hall—bolts of brilliant and electric fire flashed between us.

We were invincible.

And then there was Margaret.

She was there, but barely … a drab thing, all beiges and tans and shapeless clothing and short, tangled hair that robbed her of her sex. There one evening at a reception for his college; I the one out of place in this crowd, listening to recitations of Chaucer and Beowulf and Plato, incantations designed to winkle out some ancient and chthonic god. I thought of Druids circling Stonehenge under dark winter skies, of war-madded Spartans goading themselves to battle.

Margaret, a planet to Timothy’s dim sun, a foxed and spotted mirror to his wan, pale light, never challenging, never daring, never her own person, content to turn her pale, mottled and moon-round face to his.

There again, tucked away into some oak-shaded corner of the quad, heads bent together in some shared thing, noticing no one but themselves, not even me who stood there, mouth agape, until prudence impelled me away. Did she not know, I thought? Could she not tell?

Had he not told her?

“Who is she?” I asked, one day, when I could no longer stand it.

He looked at me, eyes welling. “She is what I need right now.”

“I thought I was that.”

He looked away, into the gathering spring as the year —our last—wound down. “I can’t. Do this thing.”

“Well,” I replied.

And that was that.

•

“Sad,” Lou murmured. I shrugged.

“How did you know?” I asked.

“I’m not sure,” she answered. “I suppose one might call it feminine intuition, if there’s such a thing. I’m not sure there is; I’ve seen plenty of stupid women who should have known better. Plus, I’ve seen it before.”

I began to stand up. “Maybe I should go.” Part of me was irked, somehow, by her forwardness. My story was my story, sad or not; with its telling, it came out sounding … I don’t know, tawdry, perhaps. Perverted. And that was one thing I never, ever thought that it was or would ever be, even if it described a life I had learned to live in secret.

She leaned forward, placing a hand on my thigh to stop me. “Please, Monk. Don’t. I’m sorry. I have a mouth on me and no brain to stop it. And the gin doesn’t help.”

I sat back down. I liked Lou, was reluctant to leave her company.

We stared at each other until she looked away, frowning.

“What?” I volunteered, smiling.

She looked back. “Nothing. But …”

“Yes?”

A truculent look crossed over her; it seemed she was fighting not me but some inner urge. Then, “You said you grew up on a farm.”

“I did.”

“Where was that?”

“You’ve never heard of it.”

“Try me.”

Fine. “Chillicothe, Ohio. Just outside.” I stared at her, expecting anything but what I got: a delighted clap of her hands, followed by a loud peal of laughter. “What?” I demanded, a bit irked. Again.

“Oh, I’m sorry. I’m not … well …” She leaned over, held out a hand. I took it. “Howdy, neighbor,” she said. Her voice, suddenly, was flatter, with a bit of half-remembered twang to it.

“How’s that, again?”

“Patsy Turner, Mr. Monk. From West Carrollton. Pleased to meet you.”

Patsy Turner? But … “Dayton,” I murmured.

“Yes. Just outside.” She grinned.

“But.”

She shrugged. “But,” she replied.

“Your voice.” Clipped, angular, precise; I’d spent part of the evening imagining English boarding schools tucked away in Surrey, young ladies in pinafores and smocks, Lewis Carroll and Beatrix Potter.

She shrugged again. “It’s what they do, if you make it. They take you and they look at you and they decide who you are, who you’ll be, who they need you to be. Patsy Turner was turned around the spit a few times and came out as Lou Whitney, vaguely from New England, vaguely well-educated, vaguely moneyed, vaguely vague. She’s brassy but always a lady in the end, can hold her own in a scrap—”

“She certainly can,” I interjected.

Lou—Patsy—nodded. “Thank you. She can probably fix a flat if she needs to, but would rather have some big, strong, strapping fellow like yourself help her out in a pinch.”

“Your voice,” I repeated.

She nodded and chuckled. “That, too. You take classes.”

“Are you Lou Whitney?”

She frowned, thinking. “Most days, I guess. Every so often Patsy turns up, mostly when I’m not working. It’s rather like having a slightly dim-witted twin sister.”

“I’d like to meet her.”

“In time, perhaps.”

“Why did you leave beautiful West Carrollton?”

She chuckled. “Animals. Plants. Acres of empty prairie. Mindless anonymity and a horrifying banality.”

“See?”

“I had a sister—well, still do, of course. She’s not dead. But she might as well be. Got pregnant at seventeen and now she’s got four kids and a husband she hardly ever sees any more, and they’re living hand to mouth. I didn’t want that.”

“So, acting. Far cry from West Carrollton.”

She grinned. “Oh, I don’t know about that. Once you get past the glamour and the costumes and the footlights and your name on the marquee and in the papers and all the accolades and an Oscar nomination, there’s not much to recommend it.”

I chuckled. “Funny; that’s exactly why I joined the Navy.”

“Well, of course. Who wouldn’t?”

Something in all that she said stuck out, so I grabbed it. “Pretending to be that which you aren’t …”

She nodded. “I was wondering when you’d see that, too. That’s why I brought it up.”

“Far easier for you to be Patsy than for me to be … me.”

“But men do it.”

“Not here.”

“You think not? This is a very artistic town, Mr. Monk. Artists, writers, actors—I think you’d be surprised. Why, I’ve even heard that their Navy might have one or two numbered among its rank.”

I smiled. “Touché. So, Stuart …”

“Of course. But every man you met from the studio today is the same as you. Some of the men downstairs in the club are, as well.”

“I think I’d noticed that, somehow. Bingham?” I had a hard time believing that.

“Even Bingham. I’ve met his boyfriend. They’re practically married. They have a perfectly divine little place up in one of the canyons.”

“Canyons …?”

“Los Angeles.”

I chuckled. “I was trying to imagine them up in the Catskills.”

“You should go to Los Angeles when you’re done navy-ing. It’s wonderful. Different. Freer.”

“Not predictable.”

She beamed. “Exactly.” She sipped another bit of the gin. “The Navy …”

“Yes?”

“Seems like an odd choice for someone of your … temperament. Big metal tubs full of virile young men, floating for weeks on end at sea.”

I grinned. “Well, when you put it that way … no, it’s different, somehow. Certainly you see a great deal, but everything is … I don’t know … ordered. Regimented. No time to … well …”

“Fraternize.”

“Exactly. It’s generally not encouraged among the men.”

“More’s the pity,” she quipped. “Is that why you joined? Couldn’t trust yourself?”

“Maybe. Punishment, perhaps.”

“For …?”

“Timothy.”

Lou’s mouth quirked. “Timothy got scared. I understand that. You don’t strike me as the kind of man who easily gets scared.”

“I don’t know.”

“That kind of world exists, Monk. I know it does; I’ve seen it. I live in it, and it can be quite lovely, most of the time. Besides, Timothy left you.”

“But—”

“I know it wouldn’t be easy. I know it’s not perfect. But it’s what you are. It’s what you can have.”

“Maybe out there. In this mythical land you call California.”

She stuck her tongue out at me. “You’re the one who talked about different countries, different customs.” She leaned back. “I don’t know—maybe California is different.” She looked me in the eye. “So, why not?”

“Why not what?”

“California.”

“I already have a day job.”

“Boatswain’s coxswain’s ensign’s mate third class?”

I chuckled. “That’s not a thing.”

Again, the tongue. “Is this what you want to do for the rest of your life?”

“It’s not a bad life.”

“It’s not a bad life, if you want it. But if you’re just running away from something …”

“Not running; just … parked, for a while.”

“Stuck in neutral.” She smirked. “I think you need someone to give you a push. Out of this unfortunate metaphor, at the very least.”

“Lou …”

She leaned forward, her face solemn and very earnest, no smile playing on those beautiful bow lips, no twinkle in those cerulean eyes. “I’m going to say something very rude, Mr. Monk. You know what? I don’t like monks. I don’t like people who hide themselves away from everybody else because they don’t think they belong. Monks strike me as being very unhappy, self-loathing people, even if they claim to be filled with the spirit of God. It’s an unrequited love at best, and a waste of a life at worst.”

I said nothing. I just stared at her. She noticed. “Nothing? Fine. I’ll go on. You may joke that you’re not an attractive person, but you’re wrong. Timothy found you attractive. You had that. And—well, why do you think I chose you?”

“Faint from hunger, perhaps. Delirious with the heat.”

She smiled. I loved seeing her smile, knew that it didn’t necessarily mean she was happy. “Jerk. No—I chose you because … well, because you’re a beautiful man, Dan Keller. No other reason.” She looked at me, hard. “At first.”

“At first.”

She looked away, looked back. “Purely visceral, at first. I admit it. If I were a different kind of woman and you a different kind of man, we’d be having a very different conversation right now, and I don’t think there’d be much actual talking.”

I grinned. “Tut, tut.”

“I warned you.”

“Why do you care so much?”

She paused. “Because I like you.”

“Lou …”

“When I realized that you weren’t … well, that you were … not interested … of course, it was a disappointment. But then, I understood that I liked you not because you were handsome—”

“Thanks.”

“Shut up.” She smiled, to take the sting out. “No … I liked you because you turned out to be the perfect gentleman, which—believe me—is a lot more important to me than how you looked.” She glared at me, still smiling. “Now you’re supposed to say ‘Thank you, Lou.’”

“Thank you, Lou.”

“See? A gentleman.”

“I’ll ask it again. Why do you care so much? After tonight, you won’t see me again.”

She raised her head, looked levelly at me down the length of her nose, very haughty and grande dame, every inch of her Lou Whitney. “Why do you say that?”

“Because …”

“Because I do this and you do that? That means we can’t be friends?”

“It makes it … difficult.”

“Absolutely.” She looked at me for a long moment, then continued. “With some people, you just know. They may not fit exactly into whatever role you initially cast them, but you just know.”

“Know what?”

“That they need to be a part of your life. That you need not to lose them. I don’t want to lose you, Dan Keller.”

“That’s … I don’t know what to say.”

She grinned. “‘Thank you, Lou.’”

I smiled. “Thank you, Lou.”

“You’re welcome. Just doing my part to bollix up the lives of everyone I meet.”

We both fell silent; not much to say after that. It had been an interesting and … disquieting evening, so far. I glanced at my watch. Lou noticed and smiled.

“Tired of us already?”

“Not at all. But I do have to get back soon.”

“Oh, of course. Curfew. Captain needs to tuck you all in every night.”

I chuckled. “Of course. That’s the other reason why I joined up.”

“I was wondering. Of course, that explains everything. I stand corrected.”

I stood up, as did she. We looked at each other; something passed between us at that point, and I realized that if I were a different kind of man and she … I shook my head, smiling, mostly at my own predicament.

A faint smile ghosted her lips. “What?”

“Nothing. I just …”

She reached out, rested a hand on my forearm. “I know.” She turned, then stopped and looked at me. “Sometimes having a good friend is better than having a lover.”

We walked together into the stairwell and back down to the club. I went over to Scotty and told him we had to get going, to start gathering everyone together. I knew the boys would be disappointed, but military—well, naval—discipline took over and soon we were gathered outside, at the curb, waiting for the fleet of limousines to take us back to the ship.

Lou went through the crowd, wishing everyone well, and the boys did me proud; to a man, they were nothing but polite and well-mannered as they thanked her for her generosity. Sailors always seem to conjure up, for most people, images of rough and rude men, but discipline beats something into you at some point, forces good behavior on you because if you refuse, you generally don’t make it very far.

And, let’s face it, Lou herself seemed to command something from people. You wanted to be nice to her, wanted her to like you. That was her secret, I realized; it must have been the secret that impelled many young women to choose this kind of life. It was more than her beauty, I realized, more than how she dressed. If Lou Whitney was a fiction, it was a very nice fiction to get lost in.

•

Presently, the Cadillacs rounded the corner and pulled up in a long line at the curb, glittering like beetles under the street lamps. Chauffeurs stepped out and began ushering the boys inside. Without me noticing, Lou managed to guide me back to the last car, where Scotty, Nick and Pete waited, talking quietly amongst themselves.

The chauffeur for this car was as brisk and efficient as the others, and the three of them climbed in. Lou pulled me aside one last time. “Our intrepid heroine wishes to say one last thing to her magnificent hero,” she said, her voice quiet, barely audible.

I rolled my eyes. “Oh, Lord.”

She smiled. “You’re really not going to like this one.”

“I’m not sure what else there is to ask. I think I’ve told you my entire life story. Such as it is.”

She opened her mouth to speak, but then the chauffeur stepped over, interrupting her.

“We’re ready to go, ma’am.”

“Oh. Okay. I’ll be quick.”

“Yes, ma’am.” He stepped away and into the Cadillac, started it up with a low, silky rumble.

Lou turned back to me, pursed her lips for a brief moment. “You know I like you, Monk.”

“Yes. For whatever reason. If it means anything, I like you, too.”

“Of course you do. I’m the annoying little sister you never had.” I chuckled; she went on. “The one who tells you what’s good for you, even if you can’t see it yourself.”

“Oh, Lord,” I repeated.

“I told you—you’re not going to like it.”

I grinned. “Don’t make me slug you again.”

She leaned in, pitched her voice so that only I could hear it. “Earlier, when we were talking about Scotty.”

“Were we?” I’d forgotten. Scotty?

“Yes. You said that Scotty was in love with me. I said he wasn’t, that he was in love with the girl on the screen.”

“Okay. I get that.”

“But … Scotty is in love with somebody real. It’s just not me.”

I was tired of talking about Scotty, let a little bit of my exasperation slip into my response. “Fine. I’ll play along. Who’s he in love with?” Racking my brain for any memory of Scotty talking about a girl, getting a letter or a postcard, or taking the day to go visit someone.

She smiled, slyly, her own version of the Cheshire Cat she’d accused me of being. “Really, Monk? You can’t think of anybody Scotty could be in love with?”

“Lou, I have no idea who Scotty’s been seeing. Nobody, as far as I know. I think he would have told me at some point.”

“No? Somebody he sees practically every day of his life? Someone he doesn’t really have to tell?”

And then I understood. She watched my face. “I told you you weren’t going to like it,” she murmured.

“You’re serious.”

“About this, yes. Never more so.”

“Lou …”

“I’m sure of it.”

“More of your feminine intuition?”

She sighed. “It doesn’t take a lot to see it, if you know what to look for. I do.”

I thought about it, thought about the three years Scotty and I had spent in each other’s company, in a ship full of hundreds of men. If I looked back, I could see it, could see that we’d been around each other far more than most of the men. Scotty was younger—several years younger, nineteen to my twenty-seven—and more in need of someone to show him the ropes, show him how things were done. And I’d done that. I thought it had been more of a big brother kind of thing, but … well, there was this evening, when he’d come to my berth after he’d showered, to tell me about Lou and the invitation to the club. He’d been nearly naked, hadn’t minded when he’d sat on my bunk in his towel. I could think of other times like that, but things like that happened all the time, were naturally going to happen in a ship. You see things and you ignore them because you have to, because if you don’t …

I hadn’t really minded Scotty latching onto me, had actually rather enjoyed it, had been flattered that he’d picked me; things like that happened often onboard, only because these are the only people you’re probably going to be able to befriend, and it’s better to be friends with someone than enemies. I thought about college, and Timothy, and how close some of the men had been with each other; the same was true, I thought, about shipboard life, even if it never consummated itself in the manner in which Timothy and I had done that one miraculous October afternoon, when most of the rest of campus was at some football game. We could hear the roar of the crowd from our room as we made love, laughed that they must have been cheering for us.

I sighed. “Lou …”

“Monk …”

“I don’t—”

She held up a hand, stopping me. “It’s there, Monk. It’s there if you want to see it. It’s there if you want it.”

“I’m not sure …”

She put a finger on my lips, silencing me. “Don’t lose him, Monk. Don’t lose sight of him. He’s a beautiful boy, and he loves you, and you deserve him. You’ll know when it’s time, Monk. I promise. You’ll know when it’s time to leave that ship of yours. Just make sure he’s with you. And don’t lose sight of me, either.”

I opened my mouth to speak; before I could, she leaned up and grasped my jaw, pulling me towards her, and then she kissed me. I could feel myself responding. A hint of her perfume drifted up into my nostrils; I nearly swooned. I understood a little of what other men must feel, in the presence of such loveliness, how it completely and utterly took control of that part of you that didn’t think so much as felt and intuited that this was the only thing possible. I’d felt that with Timothy.

If I were a different kind of man …

Even as she kissed me, she fumbled something, a piece of paper, into my hand; without looking at it, I slipped it into my pocket. I thought I knew what it was, what it had to be.

She released me, stepped back into the shadows. I turned to the waiting car and stepped into the plush, coffin-like interior even as the chauffeur began easing the door shut behind me.

I turned to Scotty, wedged in beside me on the mohair seat. He’d been playing with some of the switches in the compartment; an overhead light shone down upon him, highlighting his handsome face. He smiled. The loose curls of his hair glistened like new copper.

“What was it like, Monk? When she kissed you?”

And I realized then that I desperately wanted to show him.

[1] Foursquare is a type of house common to the American Midwest: two stories, four rooms down and four up. See American Foursquare at Wikipedia.