Dodd Forrest

CHAPTER EIGHT

Doctor Harvey Bloom was not a drunk. True, there had been a time when he tippled too much, but he’d seen where that was taking him and put a stop to it.

Harvey was from northern New York, the Adirondack country. He’d had a profitable, pleasant country practice there, and a good life. He had a lovely wife and three beautiful children. His home was nestled on a hillside among pines and maples. He was a leader of his community and his church, not only because of his education and position, but because of his friendly and generous personality. His life was full. He was truly blessed.

He had, for a year, spent all his evenings in the Silver Strike Hotel saloon, pouring down whiskey—wondering why God had let it happen, wondering why he had chosen to live rather than to die with them. The wind had blown over the oil lamp which the children insisted be left burning in their room. His wife became aware of the fire while he was still sleeping. She rushed to the children’s room and entered it just as the roof over that portion of the house collapsed. It was that sound that woke him and for two years he’d hated God for letting that happen. If he’d remained asleep, he would have died of asphyxiation—he would have died with them. As he watched, that whole half of the house collapsed into a burning hell.

He thought of jumping into the fiery abyss himself but could not bring himself to do it. For that, he had hated himself. He jumped instead out of a second floor window and broke both legs. He was able to pull himself away from the unbearable heat but could not go for help. He lay there, helpless, while his life crackled and hissed and roared and crashed and finally dissipated in black smoke in the bright starry sky.

The fire had burned so hot that nothing could be found of his loved ones. He had tried to be a man, to buck up to his grief. He continued his practice, tried to move on. He did what he thought God and his family would have wanted him to do. But then they brought little Gutrude Schlaginhof to him. She was six, the same age as his Marie. Her mother had been heating wash water over a fire outside the washhouse. The very active, very curious Gutrude had climbed a tree over the trestle that held the boiling kettle. She loved the smell of wood smoke and she wanted to watch the bubbling water. The branch broke. Gutrude fell headfirst into that caldron.

The child was dead, of course, when they brought her to him but the skin and flesh on her head and upper body had simply cooked away. It was a horrible, ugly sight but he did not see Gertrude Schlaginhof. He saw Marie and Alice and little Harvey. He saw his wife and he saw no way he could go on living.

Upbringing and what was left of his faith would not allow suicide but his memories and the horror that was Gutrude drove him to western Nevada and the bar at the Silver Strike Hotel saloon.

Harvey Bloom’s transformation was sudden. One night as he threw down a jigger of whiskey, he caught his image in the mirror behind the bar. His eyes were sunken and his skin was sallow. He was thin and pallid, a mere shadow of his former robust self. The man he saw he would formerly have viewed with a confused mixture of compassion and disgust.

It might have been the alcohol. It might have been his depression. It was probably God. In his mind that pitiful visage was replaced by the image of what he had been—a man of glowing health who loved and was loved. He saw that man being loved and admired by three beautiful children and in shocked horror it occurred to him that they might be able to see him now.

He still spent his evenings in the bar but now for different reasons. Lonely evenings were still impossible for him and most of his evening work came from the bar. But he was, perhaps, not completely conscious of the real reason. He had to constantly prove to himself and to his heavenly children—if they could, indeed, see him—that he was the man they had loved and looked up to. He wanted them to know that, with God’s help, he was stronger than heartbreak and grief, that he was stronger than alcohol, that he understood that he was still a child of God and had to conduct himself as such.

This, then, was the man with whom Dodd took up partnership. Carson City was growing. Doc Bloom had almost again worn himself to a frazzle, this time not out of drunken despair but from overwork—trying alone to keep up with the medical needs of this rowdy, dangerous, growing community.

Dodd saw Elizabeth several times a week—as often as the medical demands on his time would permit. Elizabeth was still as Dodd remembered her, fun-loving and daring. She loved horses and owned several, all more spirited than most women and many men could handle. She and Dodd frequently spent their evenings together riding, Elizabeth dressed in levis and boots, much to the dismay of the more ‘proper’ ladies of the town. She seemed to be at her happiest when she had her horse at full gallop. She had always lived on the edge, and from the time she was a little girl her adventuresome nature had worried her mother, shocked the pompous, and intimidated the boys.

Elizabeth loved the wild country. The risks she took while climbing mountains gave even Dodd pause. He soon learned, however, that she knew her limits and that her exploits were not risks but a very high level of skill, confidence, and courage. Elizabeth, Dodd was to learn, loved excitement and danger and challenge but she was not a fool. There was never a hint of bravado or pretentiousness to her. She was what she was, and with all her love of adventure and excitement, what she was primarily was a lady.

They would take walks—long walks—and talk. They talked of many things but never of the one thing Dodd wanted to talk of most. He knew that it was too soon to propose marriage. He had to be sure that was really what he wanted. He had been in love with a memory. Did he love the real person?

As he spent more time with her, however, he no longer questioned his love. He knew he loved her and he wanted to tell her that. But each time he gently alluded to the subject, a wall seemed to erect itself between them. It was not a wall of rejection but, rather, it seemed, one of confusion. There was never the slightest hint that Elizabeth did not enjoy his presence, but she definitely did not know her mind concerning him.

Dodd, though he did not know the reason for her reticence, understood. Love and marriage were major decisions and had to be made with utmost care and sufficient time. He was sure she had the same questions he had, so he was willing to allow Elizabeth the time she needed. To assuage his own desire that the relationship move faster, he threw himself into his work.

As he worked, he became convinced that he had chosen the right field. He was practicing a science he loved but it was no longer merely a science. It was a drama that covered the entire spectrum of human emotion. He experienced the ecstasy of birth, the trauma and fear of injury or illness and the pathos and sometimes tragedy of death. He felt the thrill of possessing knowledge that could heal some, and the frustration and helplessness of not having enough knowledge to help others. Using the knowledge he had drove him to constantly learn more. Just as Doc Bloom did, he pored over the few medical journals that were available, and shared experiences and ideas with any of his Harvard professors and colleagues who would correspond with him.

As was Doc Bloom, Dodd quickly became respected and trusted. These were real people, the kind with whom he had grown up. They were simple, hardworking folks who needed strong bodies to perform the work necessary to feed themselves and their families. Life was important to them only so long as their bodies allowed them to be productive. The body was the essential tool of their livelihood, a tool that must be kept finely honed. One did not trust the care of that tool to just anyone. Dodd was humbled by that trust.

Some, however, assumed that death was the inevitable result of illness or injury. Such fatalism, or lack of money and unwillingness to except services gratis, frustrated both doctors. Many people who shouldn’t have died, or lived with unnecessary permanent disability. Both Doc Bloom and Dodd knew their jobs to be both healing and education and they patiently wooed those who were frightened or non-believers. They grieved at an unnecessary death and rejoiced at a strong arm that would have gone unset and been useless had they not convinced the owner or the owner’s parent to accept treatment.

It was a vital, productive life, a good life, and Dodd was happy. There remained the question of Elizabeth’s reticence but Dodd had taken his time to make life decisions and, though it was becoming more and more difficult, he thought it only fair to let Elizabeth do the same. He had a tentative sense of peace about the matter. He had no real evidence, just a feeling that it would work out.

Pete was still a very important part of Dodd’s life. He wrote at least once a week and usually received an answer from each letter. Pete’s letters were full of expressions of love for his mama and daddy and his brother. Each also contained an expression of love for Dodd and a heartfelt thanks for Dodd’s finding him a family. The letters spoke with pride of the chores he was doing to help his daddy and how he and Ervin kept their room tidy to help their mama. They told of Ervin’s new horse, of fishing, hunting, camping, and long rides—usually with his daddy and Ervin, but often it was just Pete and Ervin. They told of picnics, Sunday School, new friends, and the Schultz cousins Dodd hadn’t told him about.

Lukie had come to visit for a week. A fast friendship had been formed with both boys. Lukie wanted the boys to go to his house for a week but Pete didn’t think his daddy could spare him. Dodd smiled. He knew Pete. He remembered how Pete clung to him when they first began living together. That boy just got his daddy. He wasn’t about to leave him even for a day, much less a week.

Ervin, although he barely knew Dodd, insisted on adding a few lines to each of Pete’s letters. He didn’t know Dodd but he knew that it was because Dodd had rescued Pete that he had his mama and daddy. Ervin too loved Dodd and thanked him repeatedly.

Dodd smiled at Pete’s loving exasperation with Sim’s girls. They were his cousins and he loved them, but they were, after all, girls. Dodd both anticipated and dreaded Pete’s letters. He dreaded the reminder that he no longer had Pete with him but he felt deep satisfaction at the boy’s adjustment and happiness.

Dodd’s busy, happy, fulfilling life was, however, touched with a tinge of guilt. He knew that he must find a way to help orphaned children but there seemed no time to even devise a plan, much less put a plan into action. Two seemingly unrelated incidences developed the plan for him and drove him to action.

Although Lillian had insisted that he stay with them, Dodd had chosen to take a room in Mrs. Looney’s rooming house. He was not sure what the result or duration of his stay in Carson City would be and told Lillian that he did not want to disrupt her household for what could become an extended period of time. That was true but not the full truth. Dodd had not realized how much a part of him Pete had become and, although he loved his nephews, for now, when he was with them, he hurt. He had enough to think about with Elizabeth’s uncertainty. Time, he knew, would heal his Pete-related emotional wounds but he saw no reason to continue to irritate them. Lillian seemed to understand and did not press the issue beyond Dodd’s third refusal to accept her kind offer.

It was to Mrs. Looney’s Rooming House that little Reva Potts had been taken after Dodd had repaired her arm. It was to have been a temporary arrangement, Dodd paying for the room and extra care the child needed. But Mrs. Looney, a relatively young army widow, fell in love with the child and just kept her. Even though Dodd had paid the remainder of Pick Fillion’s bound fee, Bob Quinlen tried to collect another from Mrs. Looney. Dodd’s conversation with Quinlen was not an angry one but Quinlen took his meaning. He also took back to Sheriff Thorn and Judge Butler a growing suspicion that this Dodd Forrest was going to be trouble.

Dodd had gotten home early one evening. Elizabeth had gone with her mother to San Francisco to do some shopping and Dodd regretted that he could not spend this one of very few free evenings with her. But, as occurred each of the rare evenings he was home before her bedtime, a nightgown clad little Reva crawled onto his lap, begging for another story.

Dodd could deal with Reva. For some reason, she did not engender painful memories of Pete. He had, in fact, grown quite fond of her and amused himself as well as the child with the stories he invented. He had no idea he had such an imagination. He didn’t know where the ideas came from but he was able to spin the tale until he felt Reva relax into sleep and then he carried her off to bed.

But that evening, he was barely into his story when a frantic knocking and yelling sent him to his room for his bag. Boyd Kilmer, the slow-witted, fifty-year-old son of Simon Kilmer, a bull-headed small rancher, said his pa was hurt by a bull and looked like he needed some doctorin’. “Mama said come quick.”

Dodd knew immediately that it was serious. Simon Kilmer didn’t believe in doctors and if Sadie, just as bull-headed as her husband, was sending for a doctor, the man was probably almost dead. Boyd was not astute enough to tell Dodd the nature of his father’s injuries. He only repeated that a bull got him in an exasperated tone that suggested that if Dodd knew his doctorin’, he’d know what kind of injury a bull caused. He mirrored the haughtiness of his parents. He just didn’t have the intellect to carry it off well.

Simon was near death. Sadie said when he came home right after he got away from that damn bull, his belly hurt bad and there was blood in his shit. Dodd knew there was some internal injury but since Sadie said he seemed to be gettin’ some better and the blood had cleared up, Dodd assumed those injuries had not been too serious. But, Simon had a deep horn wound in his thigh which was now infected. He was extremely warm and delirious from the fever. That was the part that scared Sadie into sending Boyd for Dodd. “I can take care of belly hurts and cuts and such but I don’t know nothin’ about fixin’ folks who is talkin’ out of their head. You go on and fix him but I ain’t payin’ you no more than a dollar.”

Dodd tried hard to mask his exasperation. Why did these people insist on killing each other with these cow manure poultices? As Dodd began to remove it, Sadie again wanted to discuss finances. “Do what you want with that damn leg but I ain’t payin’ for nothin’ but fixin’ his head.”

“It’s what’s happening in this leg that’s causing him to be out of his head.”

“I never heard of nothin’ that dumb. A hurt leg is a pure distance from a head. Can’t be no hurt leg put a man out of his head.”

Dodd was patient. “Sadie, now, you know Simon has a fever. You know how hot he is. That fever is from the infection in this leg wound.”

Sadie interrupted, “Hell, I know infection when I see it. What the hell you think I put that cow shit poultice on him for?”

“You tried to do the right thing, Sadie, but it’s the manure that’s making the infection worse.”

“What kind of bullshit is that? My mama and her mama and her mama before her been usin’ cow shit poultices. Everybody knows cow shit draws out the poison.”

“You’re right, Sadie, cow manure does draw but it has too much bacteria…”

“That’s the trouble with you book learned doctors. You know all them words that don’t mean nothin…”

“Sadie, a man by the name of Louis Pasteur in France found out that little bugs, so tiny you can’t see them, cause infection. Most people call them germs but the correct name is bacteria…”

He was beginning to make sense. Sadie had heard of germs. “I hear tell of germs. You mean that French found germs in cow shit?”

“Sadie, germs are all around us. Unless we get a wound like Simon has, they can’t hurt us. But if they get in a body, they can do some harm.”

“Was that French lookin’ at Nevada cow shit?”

“Probably not.”

“Well, there you are. French cow shit is probably different from Nevada cow shit.”

Dodd did not wish to pursue a discussion on the properties of foreign and domestic manure. He wanted to get at the treatment of the wound. “I don’t know about that but Simon got some germs from somewhere or he wouldn’t have an infection. An Englishman by the name of Joseph Lister found some things that can kill germs just a few years ago. Can you get me some hot water and lye soap? I want to wash this out good and then I want you to leave your poultice off for three days. I’m going to put on some carbolic acid. Look at me, Sadie. I want you to promise me that you will give my way three days. If Simon’s leg and his head aren’t both some better by then, you can go back to your poultice. Will you do that?”

It was the idea of germs that made Sadie agree. She was afraid of germs. A lot of folks was sayin’ that germs can raise all kinds of hell with you. She didn’t think much of Dodd’s idea that Simon’s hurt leg was puttin’ him out of his head and she didn’t know why Dodd was payin’ attention to all them damn foreigners but the poultices wasn’t makin’ Simon no better and, from what she’d heard, could be germs causin’ all the trouble. She didn’t like giving in but she wasn’t takin’ no chances. She didn’t like the idea of Simon dyin’ from germs more so she’d give Dodd his three days.

While Dodd worked on the wound, Simon maintained a continuous line of chatter. Dodd quickly became very interested because what Simon was saying was the result of reduced inhibition, not delusion. Simon ranted about his bound-boy runnin’ off. “Paid a hundred dollars for that little bastard and as soon as he got big enough to do some real work, he run off. And, that ain’t the worst of it. Damn Quinlen wants a hundred-fifty now for one ain’t big enough to see over the back of a six month calf. That’s all he’s got no more. Damn Judge Butler makin’ all the Ormsby County orphans go to school. Whoever heard of such a thing. It’s that damn Hatcher at the bank and that damn Josh Forrest. Who the hell they think they are? Judge Butler’s a good man but them two high and mightys makin’ him send them orphans to school. Dumbest goddam thing I ever heard of.

“But they ain’t as smart as they think they is. Quinlen is sendin’ all them boys when they get big enough to Douglas County. Judge there ain’t makin’ them boys go to school so they can sell them out and folks is buyin’ them and puttin’ them to work in the mine. Hell, the mine pays them boys a half dollar a day. Take less than a year to get your money back and start makin’ a profit.”

Dodd tried not to act too interested. Sadie was right over his shoulder. “Those boys working in Forrest mines?”

“Hell, yes. You a dumb ass for askin’ that. Ain’t no other mines around here.”

Dodd finished scrubbing the wound and applied carbolic acid salve. He gave a supply to Sadie with instructions to do the same for the next three days. If he wasn’t any better by then, she could send for Dodd again or go back to her poultices. Dodd didn’t tell Sadie this, but if Simon hadn’t improved after three days he would die and it didn’t make any difference what was put on the wound.

Simon Kilmer would eventually recover and both he and Sadie became believers. There would be no more manure poultices at the Kilmers’, and Dodd and Doc Bloom noticed a distinct rise in business from the Kilmers’ neighbors.

Dodd did not know as he was leaving the Kilmers’ that night that Simon would recover but he was convinced that he would not. He had never been so angry. His own brother was putting children, perhaps as young as eight years old, in the mines. Quinlen was operating a slave market and he was now sure how much money was involved. Somehow, he had to get a look at the county books to see how much of that money was being turned over to the county. He was sure he could not stop Quinlen, Thorn and Butler on a plea of compassion for the children. This was hard country and compassion, particularly for those who were costing tax money, was an extremely rare commodity. But, if he could show that hard-working folks were being cheated out of tax money, then he would get some support. It probably wouldn’t change attitudes toward children but it would get rid of Quinlen, Thorn and Butler. That would be a start.

Josh Forrest was almost in a state of shock. He had never seen his little brother so angry and, after a half hour of listening to him rant, Josh still hadn’t figured the reason for Dodd’s rage. It had something to do with the mine and young boys working there but why should that be a problem? Since the lode had been discovered and they started drifting into mountain sides, small boys had been used. When the vein was thin, it could be followed farther with a small body. Some of his men brought their sons to be hired. Boys worked on ranches. Boys had always worked. What was Dodd thinking? Josh had told his father that it wasn’t a good idea to let Dodd go to Harvard. He knew the boy would get some of those outrageous eastern ideas.

“Dodd, you just settle down. We’ve never had a boy hurt. If we’re going to blast, I’ve sent orders to see that the boys are completely out of the mine. Who’s going to take care of those boys if they don’t work?”

“Why don’t you take Joshua down there and put him to work?”

“Okay, we’re more fortunate than most. I wouldn’t want Joshua down there, but then he won’t starve if he doesn’t work. It’s done all over, Dodd. You’ve been east. They work children in coal mines. They work them in textile mills—both boys and girls. I won’t let them send a girl down the mine.”

“So you’d let the girls starve?”

“No sense trying to talk to you until you settle down. I’ve heard stories about children losing hands and arms in some of those looms and spinning rigs. I’ll say again, we never had a boy hurt and using boys is good business.”

“I know there are still many problems but Massachusetts has had laws limiting the length of the work day for children for years. How long do you keep those boys in the mine, Josh?”

“They work a regular twelve-hour shift.”

“So they go in before light and come out after dark. You have children as young as eight years old who never see the light of day.”

“They do, too. We never work anyone on Sunday.” Josh’s responses were beginning to sound defensive.

“Do you know what they do on Sunday, Josh? They sleep all day. You’ve seen them sleeping in church. Some of them are so dead tired they can’t even be awakened to walk out of the church. How many boys who work for you have you seen carried out after service by their daddies, who are almost as tired? These children are worn out and many of them are sick. You can’t keep a growing, developing child in that dampness or dust and expect it not to affect them.”

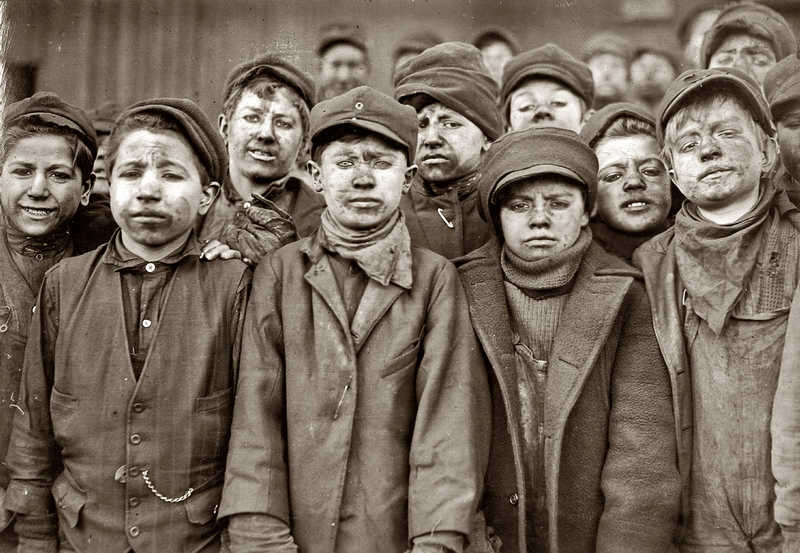

Breaker boys, aged 12-13, Pennsylvania, 1911

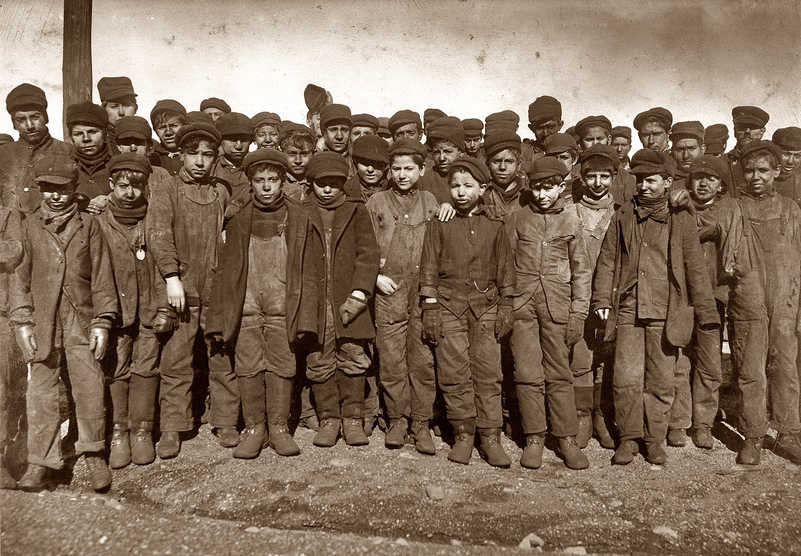

Young coal sorters, Pennsylvania, 1911

Josh had no retort to that. He could not argue medical issues and he had never thought that working in the mine might be harming the children’s health. He seemed for a moment to have lost the argument but a too-common and too-accepted practice occurred to him. “I don’t understand why you’re so upset. Do you have any idea what might happen to these children if we didn’t hire them? There are always men around trying to buy children to take them to the cities for prostitution. They take boys and girls to New Orleans, Philadelphia, New York, who knows where.

“Have you ever heard of a peg house, Dodd? If we didn’t hire these boys they could end up in San Francisco to be used by sailors and miners. James says they’re trying to close them down but they’re still a whole lot of them there. Wouldn’t you rather have a boy in a mine than sitting with a wooden peg up his rear, stretching him out so that someone can use him like a woman?”

“Do you hear yourself, Josh? You’re taking what is perhaps the most despicable thing that can happen and using it as an excuse for doing something almost as despicable. You’re saying there are only two choices. Either put them in a mine or a mill from before dawn until after dark, or they’ll be raped.

“I know those places exist and they have to be stopped. When I was reading the law, several of us tried to advocate for those children but it was almost hopeless. You’d be shocked if you knew the identity of some of the people who patronize those places. They’re people of wealth and power. They want to keep children in those conditions for perverted reasons. Others want to keep children in their present condition for economic reasons. One is as bad as the other as far as I’m concerned. Saying it’s either slavery or that is ridiculous. There is another way.”

“What?”

“Treat them as much as possible as you treat your children. They may not have parents but we can let them be children.”

“Who’s going to pay to raise them?”

“We should—society.”

“You want to leave children in orphanages all their lives? You think I’m being cruel putting them in a mine; I think an orphanage in much more cruel. Have you ever been to the Ormsby County Orphanage?”

“No.”

“Well, don’t have so much to say until you know what you’re talking about. If I had to make a choice between the two, I’d much rather have Joshua in a mine.”

“We need to pass some laws and make counties run better orphanages.”

“There’s not a thing wrong with the way things are done now. These children get homes. Good Lord, Dodd, they have families.”

“Do you know that people are going to Douglas County and buying boys to put to work in your mine? The judge up there doesn’t make them go to school. They’re Douglas County wards but they’re working in your mine. They’re bought and sold like cattle. People in Ormsby County buy them. They don’t have families, they have owners. The half dollar a day you pay them is taken from them. The boy doesn’t get a thing, barely enough to eat, rags to wear and he’s a slave. Is that what you call a family?”

“Now that’s not true. That’s just not true. How do you know that?”

“I’m a doctor, Josh. I get around the community. I get into people’s homes. People in semi-delirious states say things. It’s true, Josh. It’s true.”

“I don’t believe it.”

“You don’t want to believe it. I hope it’s because that kind of cruelty just never entered your mind. If I thought you chose not to believe it because you can make money off those boys, as much as I love you, big brother, I swear, I’d knock you down.

“I don’t like being angry with you but what you’re doing is wrong. Pete was once one of those boys. Look what he’s become already. He’s a boy who is intelligent, witty, playful and very loving, and he’s made your brother very happy. He’s a child of God, Josh. They all are children of God. Who knows what they could become if they had a chance?

“I won’t mention it to you again but I can’t stop fighting for what I believe is right. I’ll do everything in my power to see that children are treated with the respect due to a child of God—and that includes stopping those children from being sent into the mine.”

Josh Forrest remained his jovial, mischievous self but in his more pensive moments the argument seemed always to be in his mind. He did not understand the faint sense of guilt he felt. He was doing nothing that others were not doing. He was paying a better wage to the boys than was paid to most men. He was a good man. He loved his family. He went to church every Sunday and tried hard to live what he heard preached there. He often gave money to people in need. He was keeping those boys from starving or perhaps worse. He knew all people were children of God. He did care about them. In his mind he had nothing to feel guilty about, but he could not shake that subtle, nagging feeling. Of course, he wished all children could live like his. Of course, many children were treated unjustly but he and Dodd could not solve all the problems. He had told Dodd that. He wished Dodd hadn’t answered, “No we can’t but we can solve some. We can solve the ones we know about. We can solve the problems in Ormsby County. It’s an old and lame excuse, Josh. Just because we can’t solve everything, we don’t try to solve anything.”

Travis Butler was a pathetic sort of man. He tried so hard to be impressive but he had neither the experience nor the sophistication to get that done. He had wandered west from the destruction of post-Civil War Georgia. He had never read the law. Nevada state law did not require that judges be lawyers.

Carson City had only one lawyer until Elizabeth came back from the east. Luther Morrison was an adequate lawyer, and though there wasn’t much law business, he could not afford to run for judge. They paid the judge less than they paid the sheriff. Butler had been one of Thorn’s deputies. Thorn knew he could control Butler and convinced him to run. He had no competition. He had been judge for the five years that Nevada was a state.

Josh had a difficult time acting as though he were taking Butler seriously. Butler was trying to be forceful but he could not look Josh in the eye and the assertiveness in his tone was lost in his fumbling for words, which frequently when found were used improperly. It was just plain funny, this man imagining himself to be erudite and eloquent. Josh usually roared with laughter at funny things but he was able to maintain a degree of feigned decorum.

After some minutes of Butler’s gibberish, Josh realized that he was trying to tell him to have Dodd keep his nose to himself. “Keep him out of the county orphanage and make him stop bothering the county treasurer about a look at the county records. Them records ain’t nobody’s business but Fred Zander’s and mine. “Bill Thorn says, ‘Keep ’em out of the orphanage and they ain’t got no business lookin’ at them books.’”

“Well, now, Travis, I can check with Luther to be sure, but I do believe all public records are to be made available for public view. Do you really think we ought to try to keep folks from their rights?”

Bill Thorn hadn’t rehearsed Butler on a question like that so the poor man was left with nothing more to say. He left and in a few minutes, returned with Thorn. “Josh, the mine and the town have always got along just fine until them two come back from the east. Damn fool Elizabeth Hatcher tried to be a lawyer. Luther made a fool of her and Travis threw her out of his court.”

Josh chuckled. “As I recall, Elizabeth made a fool of both Luther and Travis. She knows more law than either one of them.”

“Well, no damn fool woman is gonna’ be no lawyer in Ormsby County so long as I’m sheriff. It ain’t Christian. Woman supposed to be stayin’ home having babies and doin’ for her man. It says that in the Bible.”

“You’re sure one to be quoting the Bible. How long’s it been since you’ve read the Bible or even been to church? It says other things in the Bible you sure don’t pay much attention to.”

“I reckon I know what you’re talkin’ about. I do my share of drinkin’ and I use them whores. Lot of folks think them things is wrong. They ain’t. I got my Bible learnin’ from my pa. I can’t remember what the Bible says about whiskey and whores so it can’t be that it looks bad on them. I remember real good what it says about women. It says right out a woman should do what her man tells her to do and keep her damn mouth shut in church. A courthouse is some like a church so I take that to mean the courthouse too. It’s in the Bible. There ain’t supposed to be no woman preachers or lawyers. I remember that good ’cause my pa believed them things real strong and kept tellin’ ’em to my mama and my sisters.

“Pa was a good Christian man. He went to church every Sunday. He was a deacon. Lot of folks looked up to him. He knowed his Bible and wouldn’t ’a done nothin’ the Bible was again’. But he liked his whiskey and he give me a nigger girl when I wasn’t even a popinjay boy yet. Had a belly smooth as a baby’s behind. But he said I was soon gonna’ have the need heavy on me. He said that’s what niggers and whores is for. God give boys the need long time ’fore they old enough to marry and a whole lot of times them southern ladies didn’t want to be bothered. Pa said when I got the need, go to a nigger or a whore and leave my sisters and them church girls be. Pa went to the niggers all the time when my mama didn’t want to be bothered.

“I done what he said. I never tried to touch none of my sisters and I ain’t never bothered no church girl. Might be I don’t go to church but I done all the rest of what my pa said.” That declaration of Bill Thorn’s virtue was stated in tones of sanctimonious piety.

Thorn continued, “Your brother’s been nosin’ around the orphanage and botherin’ Fred Zander. Travis says you been tellin’ him the law gives anybody the right to look at them books. Well, Josh, I’m the law in Ormsby County and I say ain’t nobody but who I say got that right.

“Now, like I said, the mine and the town’s got along real good. We don’t need your brother here stirrin’ things up.”

Josh scratched his chin as though in deep thought. “You’re right, Bill. You are the law. You have a problem with my brother, you take care of it. But I heard that Dodd went over to the orphanage with Harvey. Harvey’s Health Commissioner. He’s got every right to be in there and if he wants to take Dodd with him, that’s his right, too.”

“Well, I don’t want either of them in there. You tell them that.”

“I pay my taxes, Bill. They pay your salary. Why are you here telling me to do what you think is your job?”

Bill Thorn trembled with frustration. He and Josh Forrest had always gotten along. He had assumed that things would be no different this time. “You seen how the man fights. Only way I can keep him out is to kill him. That what you want?”

Josh stood and walked to Bill. He stood with their noses almost touching, looking Thorn hard in the eyes. “Let me just say this, Bill. There are some folks in the County who think you have something to hide. The way you feel so strongly about keeping people out, it makes me wonder. I’m quite sure I know what the law is. I know that Dodd knows what the law is. If he wants in, you better let him in.

“You say you are the law in Ormsby County. You go right ahead and think that but if you kill him it’s the laws of this state that will hang you, that is, if I don’t send my security men over to do it first.”

Thorn was now not only confused. He was scared. “Why we havin’ this problem? We always got along.”

“We’re not having a problem. You and Dodd are having a problem and I’m not going to be part of it unless something happens to Dodd. You’re going to settle your problem through the law. But should you decide to do it another way, don’t worry. If Dodd ends up dead, I promise, we’ll hang you with a new rope.”

Doc Bloom and Dodd had gone to the orphanage because Hi Dinzey came to them. He had been to the orphanage to see if he could get a bound-girl to help his wife with their new-born twins. “I think they got the grippe over there. All them young ’uns got the shits and the place smells like hell itself. You got to get over there and put a quarantine on the place. You let any of them folks out of that place, the whole damn county will be dyin’ off. I hear tell the grippe is catchin’ as hell.”

When Doc Bloom and Dodd got there, Bob Quinlen was not going to let them in. Doc Bloom said state law required that County Health Commissioners investigate possible contagious diseases. Quinlen stood defiantly in the door. Dodd moved in front of Harvey. Quinlen didn’t hesitate for a moment. As soon as Dodd made his move, he stepped aside and the two doctors entered.

Most of the children were sick. They were vomiting and had diarrhea. But it was not the unemptied slop jars that enraged the doctors so much as the general filthiness of the place. When they walked into the kitchen area, a rat was eating from an open pan of food. Quinlen chased it away. “Goddammit, that’s supper!”

“Are you going to feed that to the children after a rat’s been at it?”

“What you so fussed about? I know what I’m doing. I been running orphanages for thirty years. How long you been doing it? And I don’t see what you’re so worked up about. There’s nothing catching here. These children don’t have the grippe. They always have the shits on Monday. I think it’s because those meddling church folks won’t let us make them do chores on Sunday. ‘Sunday’s the Lords day,’ they say. ‘It’s a day of rest.’ They fill their bellies and lay around all day so they’re sick on Monday.”

Dodd had taken a handful of what the rat had been feeding on. He smelled it. “You can’t feed this to the children. It’s spoiled.”

“It can’t be spoiled. It was just made Saturday.”

“It was made Saturday and left sit out in this heat overnight and you fed it to the children on Sunday?”

“We always do. I got to please the church folks. They say it’s a sin for folks to work on Sunday so I can’t get any cooks to work on Sunday.”

“Doc Bloom asked, “Do you always cook Sunday’s food on Saturday?”

“Yes.”

“And, you say, the children are always sick on Monday?”

“It’s from the lying around.”

Doc bloom looked at Dodd. Dodd nodded.

“It’s not from lying around, Quinlen. This food spoils overnight. It’s rotten. These children are being poisoned by this rotten food.”

Harvey Bloom spoke more sharply than Dodd had ever heard him. “You have until Thursday to clean this place up. I don’t mean just the kitchen. I mean the whole place. I want the bedding washed. I want the mattresses aired. I want the floors scrubbed and, whether children are sick or not, I want those slop jars emptied as soon as they’re used. If that’s not done by Thursday, I’ll bring the State Health Commissioner in. He’ll bring his police and your buddy, Bill Thorn, won’t be able to protect you. If I ever hear of another rat in here, I go to the state. You just may go to jail, Mr. Quinlen.

“And, oh yes, I want the children’s food cooked daily and what is not eaten by the end of the day, I want thrown away. I’ll find you people who will cook for you on Sunday.

Dodd and Doc found that the regular cooks were more than willing to cook on Sunday. His story about church people was a lie. Quinlen lined his own pockets by making the Saturday help work twice as hard so he wouldn’t have to pay folks to work one day a week.

Once the orphanage employees learned that some people of community status were interested in what went on in the orphanage, they had a great deal to say. Quinlen became aware that people were talking and it frightened him. He had been doing cruel, illegal things and he no longer had the leverage to intimidate his help into silence. He thought of leaving town. He wasn’t really making that much money off the sale of those children. It wasn’t enough money to go to jail over. He could go to California. He could start over—he didn’t know at what but he was tired of children. There wasn’t any money in them anymore. Quinlen knew that Dodd wasn’t the only one fussing over orphans. He knew of other folks running orphanages who had their own Dodds. There’d soon be enough of those busybodies that you couldn’t sell children anymore. Then what would be the use of putting up with those damn brats?

Quinlen thought very hard about just leaving town but all his money was in a Forrest bank. If he drew it out, Hatcher would tell Josh and if Josh knew, Dodd would know. He was afraid of Dodd. Bob Quinlen desperately wanted to just run away but he went instead to Bill Thorn and his lackey, Travis Butler.

To verify that he was correct regarding state law on public records, Josh asked Luther Morrison exactly what the law said. Morrison said, “Of course public records are available to the general public but you’ll never get me to file a brief forcing Fred Zander to show them to anybody. That damn brother of yours is just looking to stir up trouble. He’s so taken by that Elizabeth Hatcher who thinks she’s a lawyer, and I know she put him up to it. I’ll have no truck with any man who lets a woman run him.”

Josh showed little emotion. In fact, he was amused, not angry. “Luther, I’ve been thinking about this for a long time. You’re fired. You have just shown me that you know about as much about people as you do about the law. From the time he crawled out of his crib by himself, nobody ran Dodd Forrest. If you can’t see that in him, you don’t know the first thing about people and that’s a pretty damaging quality in a lawyer.”

“You can’t fire me. There are no other lawyers in Carson City. Who’s going to do your mine legal work?” Luther Morrison’s confident smirk looked a little tentative.

Josh leaned back in his chair, his hands clasped behind his head. “I saw one beat you six ways to Christmas not too long ago and you know you were beaten. I’m giving the mine’s work to Elizabeth Hatcher. Our work is mostly business law so Travis can’t interfere and if we have to go to court here and if Travis gives us too much trouble, I’ll have Dodd handle the courtroom. Even if Travis Butler rules against him, we’ll win it on appeal.”

Morrison was visibly shaken. He could not make a living if he did not have the mine account. “What the hell does a doctor know about the law?”

Josh was enjoying this. “The boy was a lawyer before he was a doctor. When he came to Carson City, he wasn’t sure which he would practice. He saw that Doc Bloom needed help and he knew that if any real law work was to be done, there was always Elizabeth.

“Luther, I’ve got to tell you. For the last year I’ve been sending your work to my brothers and our attorneys in San Francisco to be checked. Most of your work had to be redone. You just haven’t kept up with mining law. Can’t use you anymore, Luther. I’ve been trying to think how to tell you and you made it real easy for me. Any man dumb enough to insult his client’s brother is too dumb to work for me.”

Luther Morrison was white as a sheet. He started to plead his case but Josh interrupted. “The conversation’s over, Luther. Sorry but I’m running a business. I need a lawyer who knows what she’s doing. Elizabeth Hatcher’s that lawyer. Good day, Luther.”

Bill Thorn was surprised to see Luther Morrison in the Silver Strike Saloon at eleven o’clock in the morning—stone drunk. “Luther, you old sot. Ain’t you supposed to be in your office over at the mine?”

Luther cried like a baby. “Josh Forrest just fired me. He’s going to use that damn woman. What am I going to do, Bill? I can’t make a living if I don’t have the mine account.”

“Why did he fire you, Luther?”

“Said I didn’t know the law and he was bent out of shape because I said I thought his brother was being run by that damn woman.”

Bill’s eyes flashed. “I reckoned that damn Dodd had something to do with it. Luther, you be in my office at eleven o’clock tonight. Things was goin’ just fine till he come along. We got some planning to do if we’re going to take back this town. You quit your drinkin’ now. I need you sober tonight. And, don’t worry. I can find work for you and you’ll make more money than working for the mine.”

Bill Thorn, Travis Butler, Bob Quinlen and Luther Morrison were there. The meeting stretched into the night. It took three hours for Bill Thorn to convince the others that the only solution was to kill Dodd Forrest. Dodd nosin’ around the orphanage and gettin’ folks all stirred up about the county books was the cause of the problem. Kill him, things would be back the way they was.

At first most didn’t think there was enough money involved to risk killing but Bill Thorn was adamant. Dodd had to be killed. He was too smart. He knew or could figure out too much. Everyone in that room had broken the law. If Dodd was just let go, they could all end up in jail or some, perhaps, could even feel the rope. Besides, everyone in town knew that Dodd had whipped Pick Fillion. Pick would get the blame. No one would suspect them but Bill had to be seen when it happened. He told the others of Josh’s threat. He joked, “At least the man thinks enough of me to hang me with a new rope”. They all agreed Bill could not do the killing.

Luther Morrison protested that he had broken no law. He didn’t want to be involved. He hated Dodd and wanted him killed but he had no legal culpability now and was not going to put himself in any.

Bill’s smile was almost a sneer. “Luther, you ’member those boys you took to San Francisco for me?”

“Yes, of course.”

“Where did you take them?”

“Like you said, I met the man you told me would be at the boat dock on this side of the bay. He took them.”

“You know where he took them?”

“I have no idea.”

“You ever hear of a peg house?”

Luther blanched.

“You’re capable or whatever the hell it was you said.”

“I didn’t know.” Luther could barely gasp it out.

Bill’s smirk became a complacent grin. “You’re in as deep as the rest of us, Luther. You try to leave now, I’ll arrest you for the murder of Dodd Forrest and it will be a shame you tried to resist and I had to shoot you.”

Luther could say no more. He was in shock. But Bill’s comment about sending boys to San Francisco peg houses created considerable interest among the others. Bill had told them nothing about this aspect of his business and had not shared the profits. Quinlen had wondered what became of some of the children Thorn took from the orphanage but he was too afraid to question. He still made money. He always billed the county when he got new children but usually forgot to tell them when a child left. He was often paid for years for children no longer under his care. It didn’t make him rich but it was good, easy money.

Thorn’s dealings with children, on the other hand, were much more lucrative. Prostitution houses paid an average of $500 for a nine-year-old. The boys usually went to San Francisco and the girls to New Orleans or Denver and occasionally to cities further east. While his coconspirators did not know the extent of his business, they did have some idea of the value of his chattel. It now became clear why he was so adamant about killing Dodd. He had a large financial stake to protect.

There was anger and shock. Selling children for labor was one thing but this… Quinlen, Morrison and Butler were repulsed but each knew that he was trapped in the conspiracy. None could back out but none was willing to do Bill’s killing. Bill had to be seen. The others, now not trusting Bill, wanted to be seen. They agreed that Dodd should be killed but no one present was willing to do the killing.

There was only one solution. It was dangerous to bring another person into the conspiracy but it was necessary. Pick Fillion, they were sure, would be glad to do the killing. The man had face to save. They’d offer him five hundred dollars—money he’d never get. Bill would kill him while he was resisting arrest. Bill would go to him on the pretext of paying him for the killing but he would have told around town that he was going to arrest Pick for the murder of Dodd Forrest.

Bill was extremely proud of himself. It was a perfect plan. They’d get rid of Dodd, Pick would get the blame and Pick’s children would go to the orphanage. Pick’s boy was about ten or eleven and his oldest girl was about that old. They were pretty and they would clean up good. They’d bring good money.

Thorn himself had no interest in that sort of thing. In fact he held a strong disdain for those who did, but then Thorn held a strong disdain for everyone and everything other than himself. He felt nothing about the children in whom he trafficked just as he had felt nothing about the niggers. They were money but more than that they were a means for him to exercise power. There were many ways to get money but trafficking in human beings was the only way he knew to get both money and the exhilaration of power that was his true addiction.

Copyright © 2003 Gordon L. Klopfenstein