Tinker’s Travail

by

Cole Parker

colepark@gmail.com

I stopped with my hand on the door and called back inside. “I’ll get that on the way home and bring it in tomorrow.”

“Thanks, Tinker. See you then. Don’t get anyone pregnant.”

I left with a smile on my face. Working with, well, for, Tom was great. He was so easy-going that when I’d screw up, something I did now and then like anyone not long at a job, he’d take the time to explain how whatever it was should have been done, pat me on the back, and simply forget about the screw up. The way he acted, I always tried my best never to screw up at all, and to never do the same thing wrong twice.

He didn’t care that I was gay, either, as his teasing had just shown. I’d cared for a long time, and it wasn’t till I’d graduated from Northwoods High that I came out to my friends. That none of them cared surprised me, but not that much. I had good people for friends; their reactions had merely verified that.

But this was a Midwestern town, Sycamore Falls, and many of the adults weren’t quite that open-minded. Kids for the most part didn’t follow many of the examples their parents set for them, especially when it came to this attitude. ‘For the most part’ meant just what it said; it meant a few were exempted. A few retained the old-fashioned ethos: gay was bad; gay was wrong; gay needed to be put in it’s place and expunged if possible. I was reminded of that driving home that day.

I’d stopped and picked up the part Tom needed to finish his repair. His was a fix-it shop. I assisted him and helped where I could; started occasionally when still in high school. I’d loved fixing mechanical things from early on in life.

I wasn’t really college material, and I didn’t know what I wanted to do. I loved tinkering with things. Had all my life. Tinkering, taking care of my dog, reading and swimming were the things I enjoyed most, and of those, only tinkering seemed a way to earn enough money to live on.

Tom was an expert fix-it man. He’s loved tinkering, too, and he was the one who gave me the nickname Tinker. He was the only one who used it, though. Everyone else, other than the Vaughns, called me Ash.

Tom was teaching me things I’d never known. That was another great part of working with him in the shop: gaining knowledge and experience.

He needed a new solenoid for a dishwasher he was repairing, so on the way out after work, I drove to a parts supply shop in town, and I found the one Tom needed in stock.

The problem started after I left the store.

I was in a good mood, but then saw the two guys who’d given me nothing but grief all through school, the Vaughn brothers, Carl and Tuff. Tuff wasn’t his real name. That was Toliver, but call him that and you’d be missing some teeth. Tuff fit him better anyway as it described his demeanor and conduct. I think he may have given himself that nickname; well, even if so, it suited him.

The two of them had bullied me to the extent they could get away with in a small town where their dad was someone and mine wasn’t. My name, Ashley—Ashley Cooper in full—allowed them to make a lot of ribald noise, telling everyone I had a girl’s name because that’s how I acted. They told everyone that I was only pretending to be a boy and never did it convincingly.

They liked being in fights and made fun of those of us who didn’t. I’d never been in a fight in my life. I’d been beaten on, but what’s the use of trying to fight back when it’ll just get you hurt worse and prolong it?

And they were the only ones who’d ever done that to me.

The names they’d called me and the put-downs I’d suffered weren’t good for any boy and worse for one like me, a slight and nonathletic kid who’d realized early on he was different. Also, two against one wasn’t fair, and they were always together. They were also bigger than I was, and they were rough boys looking for a target; I’d always been gentle.

No, it hadn’t been a happy childhood with those two around. They’d bullied because they thought it was fun. They’d kept telling everyone I was girly because I wouldn’t fight back and because I didn’t go out for football or wrestling or even soccer and spent too much time in the library.

They liked the audience they got when they had me surrounded and were saying things and I was cowering in front of them. Well, I’d learned by the time I was 14 not to cower. I’d just stand there and let them say whatever they wanted, just staring at them.

They got to the point where just calling me names and belittling me wasn’t enough. They kept saying Ashley in a very feminine way and asking me to prance around. I ignored everything they said, acting like a wooden post rather than a sensitive boy. They pushed me, jostled me, but didn’t hit me. They knew they couldn’t get away with that. I just took the verbal abuse. It still hurt, however. I did my best not to show it.

But then, once, they took it too far. That time, they had a larger crowd than usual, boys and girls behind the gym after school. I got the usual treatment and took it stoically as usual, but the crowd was noisy and it stirred them into doing more. Tuff was big on the ‘Ashley is a girl’ taunt, chanted in a singsong voice. This time, he told me to prove I wasn’t a girl, that I probably was, and I had to show everyone my titties; that was to prove it.

When I didn’t move, he had Carl come up behind me and grab my arms and pull them behind my back. He held them there. I still didn’t say a word. I didn’t see where it would help me any. They’d do what they’d do, and then life would continue.

I had a tee shirt on, and there was no way he could show everyone my titties by pulling it over my head with my arms being held like they were. So he did what he thought was the perfect thing. He ripped it in two and let it flop open, hanging on my shoulders, showing my chest and stomach to the crowd.

By the look on Tuff’s face, I think he really had begun believing his own taunt; he’d never been accused of being smart; he looked surprised, quite disappointed in fact, that no girly titties were exposed.

Some in the crowd were now turning, getting on Tuff rather than egging him on. Many were compassionate; there were a few, though, who urged him to go farther. I couldn’t really separate all the voices and statements because they all were coming at the same time, overlapping each other, but I thought I heard: “Thought you were proving he’s a girl!” “He’s no girl.” “My little sister is built better than that and she’s only ten!” “He sure looks like a boy to me.” “You ain’t proved shit, Tuff!”

It was all too much for Tuff. He was being challenged. He was glaring at me, then at the crowd, then at me as though this was my fault, and he was getting madder and madder by the second. Then one voice stood out; I never did know who said it. “Maybe he’s one of those hermaphrotidies, Tuff!”

That was it. I never really knew if Tuff even knew what that word—or what that mispronounced word—meant. Maybe he did, though, because what he did then was grab my jeans at my hips and yank down.

I was slim and definitely didn’t have a girl’s wide hips. My jeans and underwear dropped down right to my ankles, and there I was, showing everyone in that crowd what a teen boy going through puberty who was definitely a boy looked like without any covering garments.

Everyone saw I wasn’t a girl. Even the teacher who had come up just at the right moment and saw the pantsing. I was horribly embarrassed; Tuff and Carl were in trouble. Both got suspended for two weeks. My dad filed charges at the police station for assault, and both boys were arrested. Only their dad’s intervention and maybe some money saved them from being sent to a juvenile facility.

But the suspensions meant they fell way behind in their schoolwork, and when they came back, they never bothered to make up any of their missed assignments, and so both failed and had to retake that year of school, meaning they had far less contact with me.

My dad went to court and had a restraining order filed against the two brothers. If they weren’t being sent away, at least with the order in place they’d no longer have access to me. I guess they were spoken to severely enough about that order and what would happen if they violated it, because they left me alone after that. They left me alone, but they hated me. I could easily see that in their faces when we happened upon each other.

That was always at a distance. They couldn’t come within fifty feet of me. If we were closer than that, they had to retreat immediately or it would be a violation of the court order and they’d no longer be a problem for me in the immediate future. Jail time was called for in the order, and they’d be spending some time in the cooler.

Why did they hate me? I always wondered about that. Was it for not fighting back? I could never quite figure out the why of the hatred, but they sure had it. I wasn’t out, so it couldn’t have been that, unless they were just guessing. They looked like lit powder kegs ready to explode whenever they saw me, and often I saw Carl put a hand on Tuff’s arm to hold him at bay. They both knew, however, they’d be in big trouble if they did anything. So I learned to ignore them and ignore their hate-filled glares.

I was always aware of them, though, and when I left the parts supply store that early evening and saw them not far from my car, I stopped and simply looked at them.

Carl saw me first, and he grabbed Tuff’s wrist and tried to pull him away. Tuff looked back, saw me, and resisted Carl’s tug.

We were all stopped, just staring at each other. There was just about fifty feet between us. After watching them for over a minute with none of us moving, I took a step toward them. Two steps, and now we were definitely less than 50 feet apart.

I kept moving, walking slowly. I wasn’t 14 any longer or a quivering bowl of Jell-O. Carl pulled at Tuff again and said something to him, and I saw Tuff’s eyes widen and a sickly sort of grin appear on his face. He let Carl pull him away, and both of them kept moving farther and farther away as I continued forward. They were maintaining the fifty feet.

I reached my car and got in. As I was doing so, Tuff yelled at me. “Hey, fairy boy, my time’s comin’. Count on it.”

So maybe they had guessed and that was why they hated me. Didn’t matter, though. Hatred is hatred and the why isn’t that important.

I lived outside town. Dad was a vet specializing in large animal work, and his clinic and our house were both out in farm country. It was about a twenty minute drive. I’d been on this road my whole life, either in his or Mom’s car or on the school bus.

I was still allowing my heart to return to normal pumping—okay, just seeing the Vaughns brought back memories and I couldn’t keep my heart from reacting as it did—when I happened to look in my rearview mirror. I never had to do that often because nine out of ten times, the road would be clear. Today it wasn’t. Today I could see the Vaughns’ car behind me.

It was coming up fast, too.

I was driving my own car, my first one. It was an older model Nissan. Small and inexpensive as it was—it had ten years on it—it had been cheap enough that I was able to buy it. For its age it hadn’t been driven too much, and it was in decent shape; I was quite proud of it. I’d saved up enough of my own money to buy it, too. And then, well, Mom had helped, and so had Dad. Those two were funny; they spent a lot of time bickering with each other, but slept in the same bed at night, and their arguments never seemed to reach the stage of personal insults. I think it was the mental challenge of trying to outdo each other that appealed to them.

One argument had been about a boy needing to pay for his own car so he could be proud of it. That was Dad’s argument. Mom’s was more practical: how could I have a job in town if I didn’t have wheels to get me there? Dad said I could get a motorbike. Mom said it rained too often for that to be practical or safe. Back and forth they went, and I kept saving my money till I could afford something on my own.

Then, when I was just about to purchase the car I’d selected, Mom slipped me about half of what it would cost, and when she wasn’t around, Dad slipped me the rest.

Tom Mason’s fix-it shop was a financial success as it was the only place in town that did a little bit of everything, and as the owner-operator, he did it well. Electrical, plumbing, painting, gadgets, even computers and TVs. Everyone knew and loved Tom. When I asked if I could help out in the shop when I was still in high school, he took me on. Told me he didn’t make enough money to pay me even minimum wage back then, but if I wanted to work there, he could certainly teach me the trade, and he’d be retiring in a few years. The town would still need a jack-of-all-trades by then, and maybe I’d be ready. That’d be up to me.

I’d worked with him after school quite often and taken the last bus home. I’d graduated last year and gone to work for him fulltime. I was 19 years of age, now with a paycheck larger than minimum, and I was feeling fine. I didn’t need much, still living and eating at home as I was, and the paychecks before and after working fulltime had been the money I’d been saving for that car. It had stayed in the bank when my parents had stopped their arguments and was now used for gas money and incidentals.

I loved my car, but it was small, and Japanese cars were made from pretty light-weight steel. The Vaughns’ car was a full-sized late model Chevy, probably a half-ton heavier than my car and much more powerful. With my pedal to the metal, 70 mph would be about tops. They could do that in second gear.

The road was a country road, two lanes, one in each direction with shoulders that tipped away from the roadbed down into roadside ditches.

It crossed the occasional small bridge; trees, mostly sycamores, grew alongside it, and I kept thinking, if the Vaughns rammed into me and I got knocked off the road, my car could easily roll over because of the tilt of the shoulders, or I could be run right into a tree or a bridge abutment.

There was no way I could stop it from happening. I was scared. No question. My heart had resumed the pace it had taken when I’d spotted the two boys in town. The car was now about 15 or 20 feet behind me and was keeping pace with me. Then the driver honked the horn briefly. I thought they were trying to make sure I knew they were there. They wanted me scared.

Well, they’d certainly accomplished that.

In the rearview mirror, they were close enough that I could see wide smiles on their faces. I couldn’t see their eyes, but they were certainly filled with glee. They’d run me off the road, quite possibly kill me, and who knows if anyone would ever know how I’d happened to flip my car on a road I knew like the back of my hand?

“He was driving way too fast for the road,” I could imagine the sheriff saying, telling my parents they no longer had a son. “Teens, you know? They drive too fast. He should have known better. Dumb kids!”

The sheriff wasn’t a nice man.

The Chevy, still close behind, began pulling out into the oncoming lane, moving forward, and I had to quickly move into that lane myself to keep them from pulling alongside me. That didn’t work for them and they fell back again. This happened several times before their plan changed. Instead of pulling up beside me, they began closing in on my back bumper before retreating.

I slowed down. This was much too fast, and if I crashed, I wanted it to be at 30, not 70 mph. The Chevy fell in behind me again, matching my speed. Then it moved forward and just gently nudged my back bumper. I felt it. My first reaction was to speed up again, but I resisted; slower was safer. Just like being a wooden post had been.

I had to think of a way out of this. I had to.

They fell back again, maybe even a little farther than 20 feet. Tuff was driving. If it had been Carl, I’d not have been quite as worried. Tuff, well, I didn’t know what to expect, but knew he was out of control most of the time. Rarely would he think ahead about consequences.

What he did was suddenly speed up and come up behind me quickly, only slowing at the last second, but not enough. His nudge this time was a solid bump.

I had to fight to control the wheel, but I managed to keep the car going straight. Just barely managed. I was sweating badly now. Scared for my life.

He fell back again, ever farther. He was playing a game with me, a cat-and-mouse sort of game. I’d be lucky to survive it. I had to do something. Just accepting this was like standing and taking all his abuse back in high school, but this wasn’t name calling. This was a deadly business.

I was older now. Not a quivering mess of a boy. But I still was scared like one.

He fell back again, much farther, maybe even 50 feet. Maybe he decided we’d played long enough, or he had that 50-foot restraining order in mind. Glancing ahead, I saw a bridge abutment quite a ways ahead. No question I’d die if I ran into that, even at 30 mph. The Nissan would probably disintegrate. No protection at all.

He started forward, fast, chirping his wheels at the start, and he was accelerating. On he came, getting huge in my rearview mirror.

I tightened my seatbelt and slammed on my brakes.

The crash was tremendous. I was as ready as I could be for it. I had a tight grip on the steering wheel, I had my wheels set straight ahead, and I had my head back against the head support attached to my seat. I had all my weight on the brake pedal, and had yanked the emergency brake lever up. I’d thought about releasing the brakes just before he hit me, maybe reducing the effect of the collision that way, but it all happened too fast. I was still braking as hard as I could when he hit me.

The car skidded rather than rolled forward for some distance after the crash, but didn’t move to either side of the road or off it, and it came to a stop sooner than I’d expected it would. Maybe fifty yards short of the bridge. The brakes held all the way.

I sat still for several moments, inventorying my various parts, looking for pain and not finding any. I was shaken up, no doubt about that, but I didn’t seem to be injured.

The engine was still running, and I turned it off. I unfastened my seatbelt, then tried the door to see if it would still open. It did, though a bit grudgingly. A quick survey showed the trunk of my car was pushed forward into my back seat, the rear window was shattered, the bumper was on the ground, the rear side windows were cracked—but that was all that was immediately apparent. Still, the car was obviously toast.

I glanced back at the car behind me. It was stopped dead in the middle of the road. I could see blood on the window of the passenger side and it appeared maybe someone—Tuff, I guessed—sprawled over the steering wheel. The front end of the car was obviously damaged, but nowhere near as badly as the rear of mine was. There was steam coming out from under the hood, and the engine had died.

I didn’t want anything to do with that car or its inhabitants. For all I knew, Carl had bumped his forehead during the crash. Maybe he, maybe both of them, weren’t wearing seatbelts. That wouldn’t have surprised me. They were the type who’d pooh-pooh anything as sissy as seatbelts.

But I had no idea if either was hurt, and if not, what they’d do to me if they could. I was sure that in their minds, I was responsible for wrecking their car. Their response to that vis-à-vis me didn’t bear thinking about. They’d already showed no worries about killing me. I wasn’t going to give them the opportunity to do so now.

It was unimaginable that I was still alive, still in one piece.

Was my car still drivable? I doubted it; it surely wasn’t repairable, but could I drive it?. I got back and turned the key. It started up just like it hadn’t just been annihilated. I put it in drive, released the hand brake, and it moved forward. The steering still worked, and touching the foot brake pedal showed they were still working. The rear end felt squishy and wobbly, and I drove home very slowly, hoping the rear end would stay intact.

You’re not supposed to leave the scene of a crime. Did that hold true if people involved in the crime were attempting to kill you? Maybe that was something for lawyers to argue about. I didn’t spend any time thinking about it. I was shaken up and discombobulated and my thinking was fuzzy, my body shaking. I headed for home.

}} {{

The first thing I did when I got home was call the cops. I called the city cops, not the sheriff, even though what had occurred had been out in the country and so not really in the city cops’ jurisdiction. But I knew the city cops; they were customers at our shop and I was friendly with those guys. I didn’t know the sheriff at all, but he and his department had a reputation. It wasn’t a good one. I called the city cops.

They sent a car out to the site and an ambulance, too. Another one came to our house. I knew the policeman who came. We weren’t exactly friends but were friendly with each other. He was only a year or two older than I was. I’d always wondered if maybe he was gay. I knew he wasn’t dating anyone and was single.

Talking to me about the crash, he was sympathetic and supportive. He had me write out a statement of what I’d been through. I did, including all the details I could think of, starting with seeing the Vaughns in town and everything that had happened after that. I took him outside to see my car.

He radioed to the crew at the site. He found out that the ambulance had taken both Vaughn boys away. There was no official word of their condition. It was only the next day that I learned Carl was dead of a broken neck when his head had hit the window. Tuff was in the ICU; it wasn‘t known if he’d survive. He had broken ribs and a punctured lung.

Neither boy had been wearing a seatbelt.

The newspaper went into gory detail about what was termed an accident. I refused to talk to their reporter. All sorts of speculation ran through the town. The time they’d pantsed me at school was mentioned, along with the restraining order. They’d had other problems with other boys in town, and those were brought up; I wasn’t the only one they’d bullied, and they’d had a number of misdemeanor offenses as well. The tenor of the story was that these guys had been heading for trouble for a very long time.

The mumblings had about stopped when it was reported a week after the crash that Tuff had succumbed to his injuries.

Then they started again when I was arrested for vehicular manslaughter for the deaths of the two Vaughn boys.

}} {{

At my arraignment hearing before a judge, I was released on bail that my father put up. He spoke to the court-appointed lawyer who’d been with me at the hearing and was advised to hire an experienced defense attorney for me.

“I’m new to all this, and the county has a really hard prosecutor. I’d be over my head trying to get your son off on a non-guilty plea. You need a good defense lawyer, not one just starting his career.”

So my dad asked around. Everyone in town knew and liked my dad, and the general opinion was those boys got what was coming to them. Townsfolk were unhappy the sheriff and county district attorney were going after me like they were. As those two were both elected officials, word was they wouldn’t get voted back in come the next election. Our town had the largest population in the county

That didn’t do me any good right then. I couldn’t believe I was being tried for killing those two when the fact was, the Vaughns were trying to injure or kill me.

Dad found a lawyer. It would cost him big time, but the lawyer said he’d win, and he suggested we could then sue for our costs, including his fees, and for punitive damages.

I sat and spoke to the guy. He was a very confident man. Maybe defense lawyers have to be. He told me we’d win, but that I’d made it much harder.

“How did I do that?” I asked.

His name was Frederick Washburn. I was to call him Fred, which seemed wrong to me as he was in his fifties, had white hair and a regal bearing, and I was just me, an awkward, naive kid. But he was pleasant and not at all aloof, and so I did as he asked, name-wise, though I got around my discomfort by almost never using his name at all.

“Ash,” he said, answering my question, “when giving a police statement, it’s best if you stick to facts and are brief. The prosecutor will have your statement, and he’ll use it to try to crucify you. I’m going to need to protect you from your own words. Some of that won’t be easy. But you’re young and you’ll look scared and all that will help. Don’t worry too much. I almost never lose, I have loads of experience, and I won’t lose this time.”

Easy for him to say, I thought but didn’t say. I doubted anything I said would undermine his self-confidence, but I didn’t want to take that chance.

}} {{

I was so nervous, sitting at the defense table, listening to opening arguments, that all the words being said sounded like buzzing to me. I tried to keep up, but I couldn’t. I wondered if all defendants felt like this. I’d been nervous watching the jury being impaneled, them all looking doubtfully at me, but it was nothing like this.

Finally, I was called to the stand and given the oath. Then the prosecutor was given permission to approach me.

After the preliminaries, his voice became stern, much less friendly, and he asked, “Mr. Cooper, did you know those boys you killed?”

“Objection!” Fred was on his feet immediately. Calls for an assumption of fact.”

“Sustained.”

The prosecutor’s name was Bailey Stewart. He glanced at the judge, then turned back to me. “Did you know the Vaughn boys?”

“Yes, sir.”

I’d talked to Fred about this. Should I call Bailey ‘sir’? I felt much more comfortable calling adult men ‘sir’. Had been doing so all my life. Fred said it was unnecessary and made him look more important than he was. “But,” he said, “your comfort is important, too, so do as you like, but don’t think by calling him sir you’ll be currying his indulgence. You won’t.”

“And did you hate them?”

I looked at Fred. He nodded.

“Yes.”

“And did you stop your car in front of them knowing they’d be unable to stop?”

“Objection.” Fred was up again. “Calls for an opinion. There’s no way Ashley could know if they could stop, if they wanted to stop, if they intended to stop, the fitness of their brakes—” he paused for effect, then “—I could go on.”

“Sustained.”

This time Bailey rolled his eyes, but not so the judge could see him. Then back to me. “You intentionally stopped in the middle of the road; yes or no.”

“Yes, sir.” I so, so wanted to add to that, but Fred had told me not to. “Answer just the question. Explanations, excuses, apologies, anything but a yes or no can lead him into what for you could be trouble. Make him do the work. Don’t make it easy for him.”

“Did you plan on them hitting you?”

This was when I really needed to say something other than answering in the affirmative. Or the negative. Actually, he was making an assumption again. I looked at Fred. He simply looked back, but smiled. It was up to me how to handle this, but we had discussed what to do if I got into a fix.

My nervousness made thinking almost impossible, and clear thinking even harder. But I did force myself to think. Fred had said it was all right to do that, and I did. Then I said, “I decline to answer, citing my fifth amendment rights, but in no way doing so to suggest any guilt. My refusal is more a reflection on the nature of the question than anything else.”

Now it was Bailey’s turn to stop. He turned to the judge. “Can’t you stop him from making outrageous statements that aren’t responsive to the question?”

The judge fought to repress a smile. “Please move on, counselor.”

He turned back to me, annoyed and flustered. “Did you think they would hit you? Yes or no?”

“Answering ‘yes’ would be deceptive , sir, and so would answering ‘no’. I can’t answer that question without explanation. So I decline to answer.”

That pissed him off even more. “Alright, we’ll take that as a yes, that you did plan on them hitting you.”

“Objection!” Fred was up again. “He’s now instructing the jury how to interpret Ashley’s answer with an extemporaneous statement that has no basis in fact. Ashley didn’t say that at all! Counsel is giving final argument rather than questioning the witness!”

“Sustained. The jury will disregard Mr. Stewart’s final remark. Mr. Stewart, don’t do that again.”

“My apologies, your honor, I was simply trying to clarify the

defendant’s unresponsive remark.”

“Approach the bench, both of you.” The judge didn’t sound a bit pleased. She in fact sounded pissed. I couldn’t hear what she said, but she was speaking to Bailey, chewing him a new one quite apparently, and how he kept his voice so soft when replying to her when his face was so red, I didn’t know. Mr. Stewart just nodded and they returned to their positions.

“Mr. Cooper, did you have a history with those two boys?”

“Yes, sir.”

“And that history is why you hated them?”

“Yes, sir.”

“And when you braked in front of them, and they slammed into you, did you feel pleased?”

Oops, another hard question to answer. This time I knew what to say, however.

“I decline to answer. This question is like asking me if I’ve stopped shoplifting. Answering the question as asked would be misleading, no matter what I said.”

“Your honor, please instruct the defendant to answer the question and stop wasting our time!”

The judge glared at Bailey again for several seconds, then turned to me. “Why can’t you answer the question, son?” Her tone was much softer when speaking to me.

“As I said. your honor, the question as asked is ambiguous and assumes I had one thought in mind when in fact I had several. The question doesn’t allow for that; it’s a yes or no question.”

The judge thought for a moment, then said, “Please answer the question. Let your own lawyer correct impressions when it’s his turn.”

I gulped, then thought, the hell with it. “Please repeat the question,” I asked Bailey.

“Did you feel pleased when they slammed into you?”

Wow, this was much better. “No, sir.”

That startled him. But he also realized there was a trap waiting for him, so decided to move on.

“Did you know it’s illegal to stop in the middle of a highway, that you need to pull to the side and off the road before stopping?”

“Yes, sir.”

“And you stopped where you did on purpose?”

“Yes, sir.”

“So you knowingly, with intent, broke the law?”

I looked at Fred, and he gave me the slightest of nods.

“Though that never crossed my mind when I did it, I was and am now aware stopping where I did was against the law. Yes, sir.”

He was smart enough not to ask why I’d stopped there. Therein lay tigers for him. Instead, he asked, “How many other times have you willfully broken the law?”

He was sneaky, no doubt of that. If I said I didn’t know, or couldn’t remember, it would suggest I did it so often I couldn’t keep track. But if I said never, what if he had evidence of something? That would be perjury.

I had to think, and I took the time to do that, and then smiled at him. “That’s way too broad a question for me to answer intelligently. You’d have to ask about specific instances.”

“Ah, so it’s so many you can’t remember.”

“No, it’s actually so few I can’t think of a single one, but if you’re aware of one, or any, let’s discuss it or them.”

He didn’t like my answers, that was obvious by the way he was glaring at me. He continued.

“You admit you stopped in front of those boys, in fact killing them, knowing you were breaking the law

doing so? Yes or no?”

Fred had told me this was where the prosecutor would probably end up, and the best way for me to respond would be to simply say yes and not equivocate. That way it would be over and he could fix anything needing that.

I couldn’t do that, though. “I stopped, they crashed into me. They’re both now dead. I didn’t kill them, sir.”

He didn’t like the answer, but the judge’s frown caused him to move on. I’d hoped he was finished, but he wasn’t. He talked about the sheriff’s investigation and how it had found me liable for what happened, about how tragic it was that two young boys were now dead, and how negligent I’d been, doing what I did, all in the form of questions meant to sway the jury; I answered most of them by saying I didn’t know the answer to things like what the investigation had found and anything about tragedies.

Maybe those questions were posed to make me look uninformed and stupid. Then he repeated his first question. “You said you hated those two boys?”

“Yes, sir.”

“So you hated the two boys, they ran into your illegally stopped car, stopped in the middle of the road in front of them on a public highway and now they’re dead. The prosecution rests, your honor.”

“Objection. He’s testifying again! Nowhere in that diatribe is there a question that the defendant can answer. That last question was simply directed at the jury.”

“Sustained. The jury will ignore counsel’s last statement.”

}} {{

I thought it would now be my turn to testify again, this time with Fred asking the questions. Instead, Fred squeezed my shoulder and asked to have Mr. Vaughn called to the stand.

“Mr. Vaughn, the defense sympathizes with your loss. But we must move forward. How did your boys feel about gays?”

Mr. Vaughn opened his mouth, then closed it. He glared at Fred. Then Bailey stood up. “Objection. No foundation.”

The judge took a moment, then said, “Sustained.”

Fred nodded at her. “I was hoping to avoid embarrassing the witness, but if my opponent wants that, I’ll have to do what he wants.” He turned back to Mr. Vaughn. “What were your boys’ opinion of Ashley Cooper.”

“Objection. Calls for opinion.”

“Your honor, if anyone has personal knowledge of his sons’ opinion of the defendant, it would be their father, and their opinion of him points directly to motive for their actions and subsequently the defendant’s. The Vaughns’ actions are as germane to this trial as the defendant’s are. Not permitting those actions to be discovered would prevent the truth from being brought forward and so make a mockery of these proceedings.”

The judge thought again, then said, “Overruled. The witness may answer the question.”

“How did your sons feel about Ashley?” Fred asked, turning back to Mr. Vaughn.”

“They disliked him.”

“Wasn’t it stronger than that. Didn’t they bully him through school badly enough that a restraining order was needed to keep Ashley safe from them?”

“Objection! No foundation as to how this is relevant to this trial.”

“Overruled. Mr. Stewart, I’m allowing this course of questioning. Please don’t continue interrupting. The background to what occurred on that highway is indeed relevant to the case.”

“Mr. Vaughn?” Fred prompted.

“Yes, there was a restraining order.”

“And that was because of your sons’ bullying?”

“It was because the little fairy was too chicken to stand up to two decent, God-fearing, youths. Rather than stand up like a man, he ran to the police and the courts. Who does that? Huh? Huh?”

“So you agree they were bullying him. Was it because Ash was gay?”

“Objection. Speculation.”

“Overruled. The witness will answer.”

“Yes, my boys had no use for fairies.”

“And did they get that from you?”

Bailey stood up to object again, but Mr. Vaughn beat him to it.

“Damn right they did. We don’t need no fruitcakes in this town!”

“Thank you. Your honor, I’m finished with this witness.”

“Mr. Stewart?”

It looked to me like Bailey wanted to smooth troubled waters, but realized he’d probably make things worse. He shook his head, and the judge dismissed Mr. Vaughn.

My turn now. I walked to the stand and was reminded that I’d already sworn to tell the truth.

Fred took me through my history with the Vaughn boys. How they’d done what they’d done to me, how much I feared them, how they’d affected my youth. I told about the restraining order, how it had saved me recently, keeping them away from me, and how much they’d resented it.

That got an objection from Bailey.

“Objection. That’s opinion, not fact!”

“Your honor, I specifically asked for the defendant’s opinion of how those boys reacted to the restraining order. Ash certainly has an opinion of that based on how they acted when they saw him.”

“Overruled.”

Fred smiled at me. “So, on the day of the car crash—” never once did Fred call in an accident “—what was going through your mind when you saw them driving behind you.”

“I thought they’d decided that no one would know they were violating that order they so hated. They could hurt me out in the country and no one would know it was them.”

“And tell us in your own words what they did.”

Testimony that had been heard so far about the crash had come from the sheriff’s deputies who’d done the investigation. They’d simply said evidence showed I’d stopped in the roadway ahead of them and they’d been unable to stop and ran into the back of me. This was my chance to set the record straight.

“I knew they hated me. I thought it was because I was gay, but to me the reason for their hatred was immaterial. They hated me and wanted to hurt me.

“I was in trouble because their car was much faster and heavier than mine; no way could I get away from them. What they did was to race up behind me, then almost crash into me but slow down just in time. They did that several times, and then they actually nudged me, first very soft, the next time hard enough I had to fight the steering wheel to stay on the road. I could see them laughing, knowing how frightened I was.

“I knew it was just a matter of time till they hit me. And I was scared because I knew it would knock me off the road. What scared me most was the thought I’d run into a tree or the bridge abutment that was just ahead. I knew I’d be hit. And the only choice I had was to have the crash happen where there was nothing on the side of the road for me to run into. Otherwise, I was sure I’d be killed.

“Then Tuff—he was driving—fell back farther than before, and when he sped up, it was clear what was coming. He’d build up more speed, as much as he could, so he could ram into me hard. He was trying to knock me off the road. It seemed to me that he was trying to kill me. Even if the crash didn’t, I’d be hurt and at their mercy.

“The Vaughn boys didn’t have any mercy in them when it came to me.”

I stopped to take a breath. Several in fact. Then I continued, my voice a bit shaky from remembering how I’d felt back then. “I saw him coming. I put on my brakes. Right where it seemed I was in the best place for this to happen. No trees, and the bridge was far enough ahead that I wouldn’t hit it. I’d probably flip over but not run into anything after that. I was going to release the brakes just before I was hit so the crash would be as gentle as I could make it. I knew it wouldn’t make much difference, but maybe it would help me just enough so I’d survive. But they came faster than I expected and I didn’t have time to release the brakes to soften the crash. I was so scared, I wasn’t thinking well. I’m surprised I didn’t pee myself.

“The prosecutor asked about my plan and about if I was happy about the boys crashing into me. That was crazy! I wasn’t thinking of them at all. I was thinking about doing the absolute best I could to survive the attack. I was only thinking about me and the situation I was in. They’d been trying to hurt me all my life, it seemed. This was just more of that, although killing me seemed likely this time. I thought they’d probably succeed this time. But that was where my mind was, not on any plan to hurt the Vaughns.”

Fred gave me a minute to compose myself, then asked, “What did you think when you were arrested, charged with their deaths?”

“I still can’t believe it. They ran into me. They meant to run into me. The whole crash occurred because they were trying to run me off the road, to hurt me. And then I get charged with their death? I still don’t believe it.”

“Thank you, Ash.”

The judge asked Bailey if he wished to cross examine me, and he said no. “The facts speak for themselves, your honor.”

“Does the defense rest, Mr. Washburn?”

“No, your honor. Please recall Deputy Meyers to the stand.”

When the deputy was again seated, Fred spoke to him from the defense table, meaning the deputy had to speak loudly in return.

“Deputy Meyers, you testified to the length of the skid marks from the defendant’s car. Did you also measure the skid marks made by the Vaughns’ car?”

“No.”

“Why not?”

“Because that car didn’t skid.”

“But it saw a stopped car in front of it! Of course it would brake, and as it was coming fast, it would have made heavy skid marks.”

“It didn’t.”

“And was there a bright sun shining in Tuff’s eyes, or heavy fog, or a curve in the road, anything so Tuff could have come on Ash’s car by surprise?”

“No, there was nothing to interfere with Tuff seeing the car stopped in front of him well in time to avoid it. Nothing at all was done to prevent the crash.”

“And in your expert opinion as an experienced traffic crash investigator, how do you explain that he took no action to avoid hitting Ash’s car? Did he at least brake at the last moment?”

“The brakes were not employed.”

“So in your opinion, the Vaughns’ car didn’t try to stop, and hit the defendant’s car in a way that had to be intentional?”

“Objection! Calls for opinion.”

“Your honor, Deputy Meyers is an expert. He gave his credentials when testifying for the prosecution. The question calls for his experienced judgment. He’s qualified to give it.”

“Overruled. The witness will answer.”

“The only logical explanation was the driver had no intention of stopping. He had time to avoid the crash by pulling around the car in front of him. He could have slowed down. He could have braked. He did none of these things. In my opinion, the only thing that makes sense is that it didn’t want to avoid hitting Ash’s car. That instead, he was trying to do just that. The crash was intentional.”

“Thank you. The defense rests, your honor.”

}} {{

My reason for breaking the law and stopping on the highway was totally ignored by Bailey in his closing statement. To him it was cut and dried. “This is a text book case of vehicular manslaughter. Mr. Cooper showed contempt for the law, breaking it twice by stopping in the middle of a highway and by leaving the scene of an accident which resulted in injuries. Because of his careless and illegal actions, two kids are dead. Do your duty and find him guilty of his crimes.”

Fred’s closing was much longer and heartrending. I’d had a childhood of abuse from those boys as had other people in town as testimony had shown. Their extensive police records and history of bullying had been detailed in the trial. It was clear what the source of their attitude was; it was supported by their father and his rabid homophobia. But the two were adults and their actions were their responsibility.

I, on the other hand, was a good kid—he really didn’t need to call me a kid, in my view—known and liked in the town where I’d grown up. I now had a job here. I was someone who never was in trouble with the law. I had been burdened by the actions of the two Vaughns, and their attitude had finally resulted in the disaster that was the cause of this legal proceeding. I was extremely fortunate to be alive. I’d feared that if I’d been injured and they hadn’t, that they’d have done to me what they always wanted; they’d shown they didn’t care if I were dead by ramming my car. So leaving the scene of the accident had been the reasonable thing for me to do, Fred acknowledged, and I’d called the police first thing when I finally felt safe from them.

He had deprecating words for the sheriff’s department, too. He called the prosecution the jury had just witnessed a witch hunt, and that his investigation in this case had resulted in his gathering of evidence of homophobic acts by that department in the past; he was considering filing a law suit against that organization.

Then he dropped what to me was a bombshell.

“I’d like to leave you with a last thought. Mr. Stewart made a big deal out of Ash breaking the law and two people are dead. He repeated it over and over. He did it to make you believe that the two go hand in hand: break a law, and if people die, you must be guilty, and you must hold the law in contempt. Well, let’s look at that for a moment. Yes, Ash broke two laws, but both were to save himself when he was being threatened. Let’s look at who else broke the law when they weren’t being threatened, weren’t under any duress.”

He paused for a moment, maybe to let the jury members cogitate. Then he continued. “You know who it was. It was the two people who died! They broke the law themselves, a law invoked specifically to save them. The law says that drivers and passengers must wear their seat belts. Neither of the Vaughns had one on. Who is to say that they’d still have died if they’d worn one? It’s more likely than not that neither would have been injured at all if they’d been more concerned with their own safety and obeyed the law than they were when attempting to knock Ash’s car off the road and likely injure him.

“So, it is your job to determine whether they died because of Ash’s actions, or because of their own? We’ll never know for sure, but it’s clear that they were just as guilty for their deaths as Ash was, and in my mind at least, much, much more responsible. To repeat Mr. Stewart’s sentiment, because of their careless and illegal actions, two kids are dead.”

He then asked for a not guilty verdict, saying anything else would be egregious. He also asked that all costs inherent in this case should be paid by the prosecution. That this case should never have come before the court.

Fred was a very charismatic speaker. I could see the faces of the jury as he spoke, and that he was reaching them. When they looked at me now, still anxious and not able to hide it, they didn’t look as grim as they had when they’d first entered the box.

The wait for the verdict to be decided and then delivered was one of the worst times of my life. But it was shorter than even Fred thought it would be: I was found not guilty. It was a total surprise for me that the jury was out deliberating less than fifteen minutes! They asked the judge if they could assign punitive damages to the prosecution, and she asked for an amount. If I got what they specified, I’d never have to work again, but I liked my job with Tom and would just put the money in the bank. Well, I would have to buy a new car.

The judge said she’d consider it.

}} {{

I was at home that evening, still feeling unsettled by everything that had happened. When there was a knock on the door, I answered it. It was the policeman who’d taken my original statement. My heart leaped. Was I being arrested again? Was their some flaw in the trial?

“Hi, Ash,” he said. He sounded nervous. Why would he be nervous talking to me?! He was a town cop and I was a nobody. “Uh, can you come outside for a few minutes. Maybe we could sit on your porch and talk?”

So maybe I wasn’t being arrested. “Sure,” I said. “You’re name’s Sandy, isn’t it?”

He grinned. “I didn’t think you’d know. Sandy MacCalder. I, uh . . . this is hard!”

We sat on the old glider we had on the front porch. It had been there all my life. We each sat on one end. He didn’t speak, just took quick looks at me.

“Why are you nervous?” I asked. “I’m the one who gets nervous talking to guys I don’t know.”

“I’m nervous because I’ve never done this before. See, there aren’t many gay people in town. I kinda thought I might be the only one in town around my age, maybe the whole county. Then I learned in court that you’re gay, too. I didn’t know.”

He stopped and turned away, then twisted back to look at me, appearing to force himself to do so. “This is the nervous part: I’ve always kinda had my eye on you. Sort of hoping about you. About the gay thing. But I didn’t think . . . I didn’t think you were gay. Now that I know . . .”

He stopped and blushed.

I’d always given him a second glance, too, when I’d seen him in town. Slim, handsome, young cop in a uniform. Of course I’d looked!

Now I could see he was nervous and fidgety, unsure of himself but taking a chance. I was like that, too.

Funny how really bad things can also bring about serendipity.

THE END

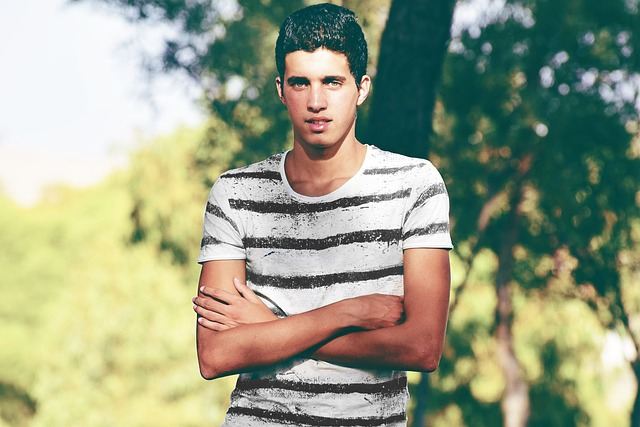

Photo credit: Pixabay.