Richie’s Outing

by

Cole Parker

colepark@gmail.com

The east wind off the ocean seemed to have teeth, even in late May. Richie shivered as he walked, pulling his arms in tight to his body, hunching over.

The weight in his pocket made his jacket sag to the right. Almost subconsciously, he gripped the gun more tightly, fitting his fingers around its body, lifting it a little so the jacket hung correctly, making the weapon less noticeable.

The church was just ahead. He turned to walk up the steps, and the wind now hit him obliquely. He was thankful when he opened the door and stepped inside. It was like walking into an oven even though the temperature inside was only in the high 60s. Being out of the wind made the difference.

Richie walked across the threadbare carpet to the church office and saw the church secretary/receptionist at her desk. He spoke to her softly, as was his manner. “Mrs. Saunders, could I see Pastor Franks?”

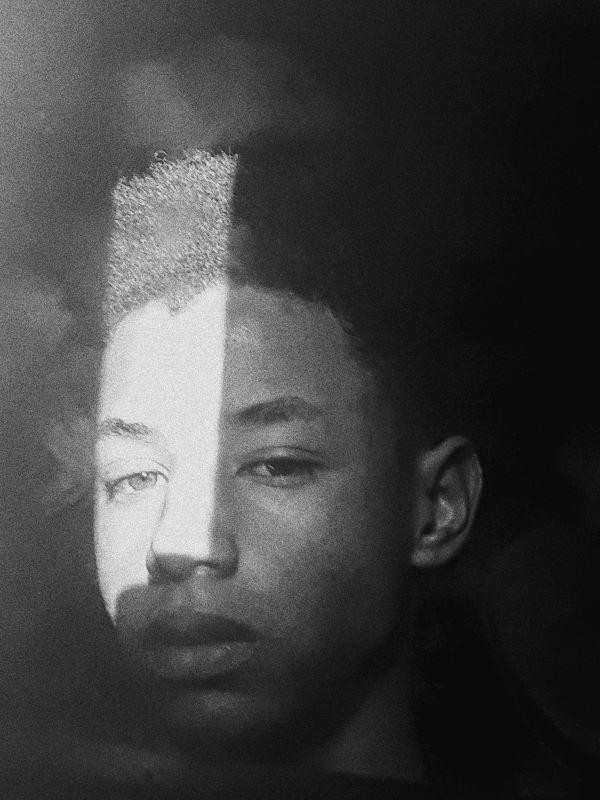

Cecilia Saunders looked up at the slight boy standing in front of her desk and smiled. She’d been working in the church office for 40 years. She’d seen pastors come and go. She’d liked some of them, disliked a few. She knew everyone in the church community and had her favorites there, too. Richie was one of them. She’d seen him grow from a sweet boy of six to his current fourteen and was well aware of the details of his troubled background and home. She could see some of that in his face as he stood before her. His skin was light brown: coffee laced heavily with cream. His face showed more anxiety than usual, and his full lips, pinched together now, looked as if they’d forgotten how to smile. Even so, he was a handsome boy.

His curly hair was cut close to his head. He wore a gray sweatshirt about a size too large, and his small frame seemed lost in it. His jacket, unzipped now, was too light for the penetrating cold of the late-spring weather.

There was worry and nervousness in his eyes that bothered her. She watched the small, shaky, twitching movements of his shoulders which seemed unrelated to the cold he’d left outside. She couldn’t see his hands because they were in his jacket pockets but thought that had she been able to, they might have been trembling. His face made her think he was reacting more to uncontrollable emotions than the season.

“Is everything all right, Richie?” she asked, her voice as soft as velvet, her eyes warm and solicitous.

He hesitated, looked into her caring face, seemed about to say something, then dropped his eyes. Glancing away, he said, “I need to see the pastor.” His voice, still soft, sounded strained, on edge.

Mrs. Saunders started to say something but saw the look on his face and changed her mind. She simply nodded and stood up from her desk. “He should be free right now. Let me just go check. I won’t be a minute.” Her concern showed on her face and in her eyes, but Richie didn’t notice, absorbed in his own world.

She rose slowly. At 75, she no longer stood nor sat swiftly. She crossed her small receptionist’s area, gave a quick knock on the door, and stepped into the pastor’s office behind it, glancing quickly back at Richie. She shut the door behind her. “Pastor, Richie Williams is here to see you again,” she said, and when he nodded, she stepped back into the reception area.

She’d indeed been gone so briefly that the second hand on her clock hadn’t made a full circle around its face. Richie apparently hadn’t moved in her absence. He still stood by her desk, his hands still in his jacket pockets. “He’ll see you now, Richie.” She tentatively reached out and touched his shoulder as he walked past her. He stopped briefly, looking up at her. She couldn’t read everything that was in his eyes but could see anguish there. Then he was gone, and she softly closed the door behind him, not pulling it quite to. She hesitated returning to her desk, wondering if there was anything she could do to help him. That he needed help was clear. And for Cecelia Saunders, it was a certainty that Pastor Franks wouldn’t be the one to provide it.

≈ ≈ 2 ≈ ≈

The pastor was a tall, thin man with jet-black skin and thick, snow-white hair. His face didn’t look old, however, and many people attending his church privately wondered if he was as old as his hair would suggest. He was wearing a severe black suit and a black tie. He always wore a black suit and tie. There was no nonsense in Pastor Franks, and no humor, either. He sat behind his desk. His Bible lay on it, the only thing on it. It lay in front of his clasped hands.

“Take that chair, Richard,” he said in his deep, stentorian voice. He never softened it, even when he was sitting five feet from the person he was speaking with. He was proud of his voice, liked the sound of it, and saw no reason to modify it.

Richie sat down. Now that he was near the man, he began trembling. He tried to stop, but couldn’t.

Pastor Frank seemed oblivious to the boy’s apparent distress. “Back so soon? How can I be of further help today?” He was either unable or felt no need to completely mask the unctuous tone he so frequently adopted when speaking to people who called on him.

Richie slowly raised his eyes to the pastor. “I don’t think you can.”

“Then why are you here?” the pastor asked, and chuckled.

Richie slowly shook his head and grimaced. Then he sat up straighter. “You remember what we talked about when I was here earlier?”

“Of course,” Pastor Franks replied. He settled back in his chair and crossed his ankles. “It was only a few hours ago. I gave a sermon last Sunday on homosexuality, how it is a sin from within, how we must face up to it if it afflicts us, how we must admit to it, how it will bring eternal damnation to those who suffer from it, how those who have fallen into its evil grasp must announce to the world the demons inhabiting them, make their suffering known so that their friends and neighbors can help rid them of this scourge, this damnation.”

His voice rose as he went through his litany, and in the wood-paneled office it bounced off the walls. That his voice pleased him was reflected in the ruddy glow in his cheeks as he spoke.

Richie sat still, watching him. When the pastor finished his oration, he came back to himself and looked at Richie. Once Richie saw that the pastor was again focusing on him instead of picturing himself in church, preaching to his congregation, he said, “That was your sermon. But, do you remember what we talked about?”

“Certainly.” A little annoyance at being questioned by one so young crept into his tone. “You said you thought you were homosexual, and that you simply had to tell someone, and you couldn’t tell your mother. You assumed that she’d never understand.”

“That wasn’t all I said,” Richie said, interrupting him before he could go on. “I said she couldn’t know, she just couldn’t. I made it clear that you mustn’t, that you couldn’t tell her.”

Pastor Franks nodded. “Yes, you did say that. But you’re a child. A mother has a right to know everything about their children, and it was my duty to tell her about your sickness so you could be cured. I couldn’t begin the aversion therapy you’ll need without her knowing. So I called her and told her. Now that she knows, we can work together to rid you of this . . . this pestilence.” He smiled, smug in the awareness of his own rectitude.

Richie didn’t waver. He always deferred to adults when he spoke to them, but his anger had been growing as he listened to the pastor pontificate, and it gave him courage. “But I also told you why she couldn’t know, why you couldn’t tell her. What did I say? Were you even listening, or had you already made up your mind you were going to out me to her? Were you already thinking that you’d look like a hero to the congregation for setting a gay boy on the path to his ‘salvation’?” His voice rose, his face flushed. “Tell me what I said. What did I say would happen if you told her?”

Pastor Franks didn’t like a young boy practically yelling at him in his own office. He was a man of God, and this young punk, this young homosexual punk, had no right to question him!

And then he saw Richie’s right hand come out of the pocket of his jacket. The pastor gasped. A pistol! The boy had a pistol! Richie set the gun in his lap but didn’t take his hand off it. The boy’s eyes were focused on his own. Pastor Franks gulped, and then in a voice that was thin and frightened and not one he’d ever have been proud of, asked, “What’s that?” It was a stupid question, but his brain suddenly seemed fuzzy. Sweat broke out on his forehead. His eyes were frozen on the gun.

“I want you to answer my question. What did I say would happen if you told my mother my secret?”

“Uh, well . . . ” Pastor Franks said and stopped. His heart was racing, and he couldn’t think. The truth was he had no idea what Richie had told him about how his mother would react to the news she had a perverted, homosexual son. He hadn’t listened at all to the boy at that point, instead thinking of the aversion-therapy sessions he would be conducting. That was exciting in itself. And then he’d pictured the claps on the back he’d be getting from the church council for turning a homosexual boy straight, the elevation of his status that would bring. But mostly, he’d been thinking of the process of the aversion therapy.

Now, he looked at the boy sitting in front of him, a pistol in his lap. And he could picture that gun being raised, being pointed at him, the boy slipping his finger inside the trigger guard . . . .

Richie broke into the pastor’s brief fugue to supply his own answer. “I’ll tell you what I said. Maybe you’ll hear it this time. Try to listen.” Richie’s anger colored his voice, making him sound older. And certainly much more frightening to the pastor. “I told you my mother would never accept me. She hates homosexuals, and if she knew I was gay . . . I told you she’d become violent. She can’t control her temper. I don’t think she wants to. I live in constant fear of her becoming angry with me, as she has in the past. I told you that if she learned I was gay, not only could I no longer live there, but maybe even my life would be over.”

Pastor Franks heard Richie this time. He wasn’t sure how to respond. Somehow, platitudes, saying ‘now now, it won’t be that bad,’ didn’t seem appropriate, not with the way Richie looked or was acting. And then, there was the gun. So the pastor did the wise thing. He said nothing.

Richie used the silence to continue. “She confronted me when I got home.” Richie had stopped trembling when his anger had taken hold. He paused, and Pastor Franks saw an opening, and hopefully a way to calm the situation, to become engaged again with the boy and maybe regain the upper hand.

“Ah, and so she’s sent you back to me? For counseling,” he said.

Richie shook his head. “No, that wasn’t what happened at all. She didn’t send me back here. She tried to kill me.”

Richie put his hand on the gun in his lap and start moving it, apparently casually and unthinkingly, but moving it so the barrel pointed this way and that. First it was pointed at the windows. Then it stopped when it was pointed at the pastor.

Pastor Franks began trembling. He was no longer leaning back in his chair with crossed ankles and a proud glow on his face. The boy in front of him seemed too angry, to determined, for the man to think somehow or other this wasn’t going to end badly. He began sweating again.

Richie picked the gun up off his lap and fit his right hand around it, moved his finger inside the trigger guard. He looked at it, then back up at the pastor. He looked into the man’s eyes and saw no signs of the smug condescension that had been there earlier.

Richie spoke slowly and deliberately. “She tried to kill me,” he said, “and I shot her. Then I came to see you.”

≈ ≈ 3 ≈ ≈

When Richie had left his meeting with Pastor Franks earlier that day, he’d been badly shaken. He’d gone to the pastor, a man he didn’t like but an authority figure he assumed he could trust, because he’d been feeling more and more that he needed to be open about his sexual orientation. Hiding who he was felt like a lie, and it was becoming more and more difficult to keep it all inside. Furthermore, he didn’t see how he’d ever have a happy life if he couldn’t find someone like himself, and if he stayed in the closet, how would he do that? The urge to find someone had been getting stronger and stronger. He saw other kids at school finding partners and starting relationships. But it was all boys finding girls and girls finding boys. That he couldn’t do the same was eating at him, making him feel there was something wrong with him.

He saw boys in school he was very attracted to, but just seeing them and not being able to do more than that was killing him.

His ‘community’ of black boys was thoroughly disgusted by gays, and totally intolerant of them. They made that very clear. He’d seen effeminate boys beaten badly and ostracized. If he came out, he was sure he’d be shown the same treatment, he’d feel fists and shoes and unremitting catcalls, he’d see backs turned on him, but he knew he could survive all that. He was a black boy growing up in a predominantly black, lower-income neighborhood. He’d been in many fights. He knew he’d get beaten, but it had happened before, and he’d survived. He would this time, too, and then, maybe then, other gay kids would know he was one of them and he’d be able to find someone who’d share his feelings. He couldn’t see any other route to happiness. He’d have to be strong, but he could do it.

His real problem wasn’t with his peers. Instead, it was what he faced in his own home. His mother was something else. There were only the two of them. His father had left over a year ago and he’d not heard anything from him since. The hurt from his abandonment was enduring, still sharp and painful. He’d loved his dad, and had been sure his dad loved him. Then, bang, he was gone, and that was it. No calls, no letters, just no dad. His mother said he’d never loved them and good riddance. Richie wanted to know why—he didn’t believe his father hadn’t loved him—but she simply stopped talking about it and told him to stop asking. But, with or without explanation, his father was gone. Richie was still trying to get over that. There was a vast emptiness inside him when he thought of his father.

If his mother refused talk about something, she simply refused, and there was nothing he could do about it. His mother was a larger-than-life figure. She was a huge woman, well over 250 pounds, maybe over 300 pounds for all he knew, and she had a furious temper. When she was mad, Richie had learned to make himself invisible. She had a baseball bat, and she broke things with it when she was mad. She’d beaten him with her fists and whipped him with a belt when he was younger. His dad had had to save him on numerous occasions. Yet even he, a full-grown man, couldn’t defend himself entirely against her when she was in one of her angry rages.

But now his dad was gone. Now, if Richie saw she was getting mad, he got out of the apartment, if he could. On more than one occasion, he’d ended up on a friend’s doorstep, looking for a place to sleep. Luckily, since his father had left, she hadn’t attacked him in one of her furies. He really didn’t know what he’d do if it happened again.

He was worried, walking home after meeting with Pastor Franks and outing himself. He’d told the pastor how important it was that his mother couldn’t know his secret. He’d told him about her frenzied anger and how she felt about gays. He’d said he’d be in serious danger if she knew, and explained why, when he’d felt he just had to tell someone about himself, about how he couldn’t keep it to himself any longer and wanted help figuring out what to do, he’d told him, the pastor, instead of his mother. But, the pastor hadn’t seemed to take what he’d said seriously. The man seemed to be on a different wavelength—sometimes thinking of other things or going off into some internal reverie when someone was talking to him, not really listening, and Richie wasn’t sure the man had really heard what he’d been saying.

Richie had walked into the apartment after seeing the pastor, feeling very uneasy if not actual fear. Everything had been silent as he’d entered. He’d taken a deep breath, trying to let some of his worries go. “Ma?” he’d called, still standing by the door. No response. He’d walked farther in and looked around. She hadn’t seemed to be home. Which was strange because she most always was. She was on a disability pension even though she wasn’t disabled, just fat. However, he knew there was lots of muscle and rage mixed with that fat. He had scars to prove it.

He’d just entered his bedroom when he’d heard a bellow and then the phone in her bedroom being slammed down. His eyes opened wide, and he thought of running, but then she was there at his bedroom door, and she was holding her baseball bat.

“You’re not my son!” she screamed. She swung her bat, smashing it into the wall. “You’re a fucking faggot!” Another wild swing, another crash and a framed, glass-covered picture lay shattered on the floor. “There aren’t any queers in my family! There never will be!” And without pause she swung the bat at him.

He was quicker than she was and was scared for his life. He dodged at the last second as the bat crashed into the wall where he’d been standing, cracking the plaster, punching a hole in the wall underneath it. She roared, freed the bat and raised it again, and he knew it was only a matter of time before she hit him with it. When she did, it would be all over. Because he also knew just hitting him wouldn't be enough for her; she wouldn’t stop.

His only chance was if he could get her away from where she was standing, blocking the door. If there was any opening at all, he might be able to escape. He might be hit by the bat; he might not get away, but a desperate hope was all he had now.

He leaped onto his bed, and she was after him just that fast. He knew he couldn’t trap himself. He waited for the next swing of the bat, and as it came, he jumped off the bed and up against the wall on the far side of it. The swing just missed, and he raced from behind the bed before she could set herself. She was still between him and the door, however.

She roared again, her anger not subsiding. She used the bat to smash across his dresser and the things on it, sending them flying. Another swing and the dresser itself fell over. Then she demolished his mirror.

He had no place to go! No place at all! After hitting the mirror a second time, sending shards of glass flying everywhere, she turned to look directly at him, then took a step toward him. He stumbled backwards as she advanced on him. Back, back, until he was against the closet door, one which folded inward and opened when pressed on. He backed into it hard enough that it opened, and he lost his balance and fell into the closet.

He knew he was dead. She’d slam the bat down on him, split his head open, and then hit him again and again, and he’d die before her fury was spent.

She saw him lying there, and her advance became more deliberate. The mad glare on her face, devoid of reason or sanity, never wavered. “I will not have a faggot for a son!” she screamed. She raised the bat as she approached, holding it directly over her head.

Richie tried to slide back, farther away. He was lying on something hard, and trying to slide made it dig into his kidney. He immediately realized what it was even as he was anticipating, dreading, the blow from the bat. With his father gone, Richie had realized his mother could go berserk at any time. He’d waited till she was out of the apartment and then searched the place, looking for the pistol he knew his father had owned. His father had left, taking nothing. No clothes, no shoes, no coats, nothing from the bathroom. He had simply gone. So, Richie’d thought, maybe he’d left his gun, too. His father had shown the gun to Richie when he first got it, showed him how it worked, and told him he’d bought it because the neighborhood they lived in had so many burglaries; he needed it to keep the family safe, and Richie needed to know how to use it in case his father was away and there was a break-in.

The thought of his mother having access to it had scared Richie enough that he’d searched for it, and he’d found it, high up in his father’s closet under some boxes of letters and documents. He’d taken it, then wondered what to do with it. He didn’t want to throw it away. The neighborhood was still unsafe, and his dad wasn’t there to protect them. But he didn’t want it where his mother would find it, either.

What he’d ended up doing was simply putting it on the floor of his closet and dropping an old shirt over it. He’d read some stories by Edgar Allan Poe in English last year and remembered The Purloined Letter. He decided a simple hiding place was better than a really clever one if his mother ever did look for it.

His mother never came into his closet. He had to do his own laundry, had been doing it since he was 12. She made him pick up his room himself, too, and he did so by throwing clothes into the closet, onto the floor, until it was time to wash them. She’d never look under that pile, even if she was hunting for the gun. Who’d hide a gun by simply putting it on the floor? No one would be dumb enough to do that.

Now, he realized it was the gun he was lying on. And that he probably had two more seconds before that bat descended on him.

She was right there, right then. He reached under him, grabbed the gun, pointed it at her, and as he saw her begin her downswing, he pulled the trigger.

≈ ≈ 4 ≈ ≈

“You shot her?” Pastor Franks looked dumbfounded.

“Yes, then I came to see you. I told you what would happen if you told her. You didn’t listen. I’m lucky I’m not dead. Except for being lucky, way lucky, I would be.”

“But why come here?”

Richie just looked at him, his eyes unreadable. He still held the gun in his hand, and looked down at it, then back at the pastor, and locked his eyes on the man’s face.

Pastor Franks began sweating again. “Surely you’re not going to shoot me! You’d go to prison. Maybe the gas chamber.”

Richie didn’t blink. “Maine doesn’t have the death penalty. But, so what, anyway? I don’t have any parents any longer. I’m an orphan, a black, 14-year-old orphan—who’s gay. Who shot his mother. My life is over, whether I shoot you or not. My life was bad before this, but because of you, now everything I had is gone. You’ve ruined it. Why not shoot you? Then me?”

“But . . . but I didn’t do anything wrong!”

“You outed me! You’re the reason I had to shoot my mother! I told you not to out me. I told you what would happen if you did! You ignored me, if you even bothered to listen to what I was saying. You ruined my life. Why shouldn’t I end yours?”

He steadied his aim, directed at Pastor Franks’ stomach.

“NO!” the pastor screamed. “No! Don’t shoot me! Please!”

Richie’s aim remained steady. His thoughts were scrambled in his head. But he never had a chance to straighten them out. He heard a sound from the outer office, and then the door burst open. Richie turned.

He couldn’t believe his eyes. “Dad? DAD?”

He was suddenly on his feet, the gun falling to the floor. He took a couple of hesitant steps, and then he was running to his father, who opened his arms, and Richie fell into them.

“Dad!” was all he could mumble, and then he was crying, sobbing, the tension of the past few hours gone in a spasm of relief.

Their hugging was brought to a brutal end. Mrs. Saunders, standing in the doorway, said, “Robert . . . .”

Robert Williams looked up from his son’s head and saw Pastor Franks standing, holding the gun, pointing it at Richie and his father. “Cecilia, call the police. This young man was going to shoot me. I want to see him in handcuffs and marched out of here.”

Richie loosed himself from his dad’s embrace and turned around, but stayed pressed against his dad. “I wasn’t going to shoot you,” he said, his voice raw. “I wanted you to feel some of the fear I was feeling. The main reason I came was to give you the gun. Then I was going to have Mrs. Saunders call the police. If they came and I still had that gun, well, everyone says they have no reluctance to shoot black teenagers. I didn’t want them to have an excuse.”

Pastor Franks scoffed, a bitter sound. “Yes, of course you were. Maybe after you shot me!”

“I’d have had a hard time doing that,” Richie replied. “The gun isn’t loaded.”

Pastor Franks looked surprised, but quickly regained his balance. “Doesn’t make any difference. You admitted you shot your mother. The police still need to be called. You’re a young punk, and homosexual, too, and should be behind bars.”

Robert squeezed Richie’s shoulder, then stepped away from him and over to the pastor. “That’s my gun, and I’ll take it.” He held out his hand. Pastor Franks looked undecided but eventually handed the gun to Robert. He in turn handed it to Mrs. Saunders who was still standing in the doorway, watching.

“Please put this in your desk for when the police ask for it. I’m not real eager to be shot, either!” Then he grinned sympathetically at Richie.

Richie wasn’t smiling back. “Uh, Dad? What the pastor just said? That I’m gay? I didn’t want you to find out that way. He told Mom, too, and she went crazy. I had to shoot her; she was about to hit me with her bat.” After saying that, he began trembling again.

Robert knelt down and took the boy in his arms again. While hugging him he asked gently, “Did you kill her?”

“No,” Richie said. “I hit her in the shoulder, and she looked more surprised than anything. She staggered back and landed sitting on my bed, holding her shoulder and looking dazed. I ran out of the room, then called 911 before coming here.”

“I know your mom. When she gets in her rages, she’ll do anything. There’s no doubt it was self-defense. But we’ll need to talk to the cops. We probably should do that right now.”

Holding Richie close, he turned and spoke to Mrs. Saunders. “Thank you, Cecilia. For everything.”

≈ ≈ 5 ≈ ≈

The police station was three blocks from the church, and they walked to it. On the way, Richie, still confused and shaky at the way things were happening, asked his dad the most important thing he had on his mind. “Dad? Why? Why’d you disappear? Why haven’t you ever come to see me, or called?”

Robert stopped walking and knelt down so he’d be eye to eye with his son. “I didn’t want to go, Richie. It killed me, doing that. But your mother . . . she thought I was having an affair because I was being secretive. You know her. She gets an idea in her head and that’s that. The day I left, you were at school. We had a big fight. She kicked me out. And when I said I was going to get custody of you, she got an attorney, told him that I’d been abusing you, and he got an immediate restraining order. I wasn’t allowed to contact you at all. I wanted to call, wanted to write, but I couldn’t. If she found out I’d done that, she’d have taken me to court, and what I was trying to do for you and for me, well, it wouldn’t have worked. I was trying all along to get set up so I could take you away from her.

“But I wasn’t in a position to take chances. I was being secretive because I was getting a loan to start a business and didn’t want anyone to know till it had gone through. Banks can be reluctant to take chances on black men, but I’d found one that would. They were in the process of vetting me. Any sort of problem would have resulted in the loan request being denied. If your mom was questioned about me, I’d never have been approved. Which of course meant I couldn’t contact you at all. Your mom would have made a huge stink and my chances of getting custody of you would have vanished.”

Robert reached out and pulled Richie to him. “It really hurt me, knowing you were on your own with no idea why I’d left. I’m sure it hurt you, too. I’m so sorry. But you couldn’t know. If you had, you might have run away to find me, or you might have confronted your mother, and I couldn’t take a chance on that. I’ve worried about you ever since leaving, though. You have no idea.”

“It did hurt, Dad. But I knew you loved me. Even though Mom said you didn’t, I never believed that.”

Robert smiled and rubbed his son’s head. “I did the only thing I knew how to do. It would be temporary, I knew that. I didn’t have any money, but if I got the loan, I could get the business started, and then I could afford to get an attorney to get the restraining order withdrawn and at least have joint custody and visiting rights. But I wanted more than that, Richie. I wanted you to come live with me.

“I did keep track of you. I was afraid of her having one of her fits and hurting you. What I did was . . . I’ve known Cecilia Saunders forever. She was a friend of your grandmother, before she passed. I had her keep a watch over you. That’s why I showed up today. She could tell something was wrong when you came back to see the pastor again, and peeked into his office and saw you had a gun. She heard what you were saying and called me. I got there as quickly as I could.”

Richie took that in, and they got up and walked silently for an entire block before Richie said, “Uh, Dad? What about, uh . . . what about what Pastor Franks said? That I’m gay.” He stopped and looked up at his dad, his worry clear on his face.

Robert stopped and looked down into his son’s eyes. His own eyes were full of love. “Richie, I don’t care if you’re . . . you’re . . . an Andalusian, whatever that is. I’ve missed you so much! What I want is to have you with me. You can help with my new business. It’s been open for two weeks now. What’s more important is we’re back together, and you don’t have to be afraid of your mom any longer. After what she did today, no judge in the world would give her custody.”

Richie had a big grin on his face and could feel some of his prior, ingrained fear slipping away. “Uh, Dad? I think an Andalusian is a dog or a horse or something.” And then he laughed, and so did his dad, and they embraced. Richie couldn’t remember ever feeling so happy.

Robert roared with laughter. “Well, maybe it is, smart ass, but I think it’s some sort of human, too. A Spaniard, I think.”

When they reached the police station, Robert gave his name and said he was the husband of the woman who’d been shot and that his son had been the one who’d shot her, in self-defense, and the one who’d called 911 to report it.

The sergeant looked through some papers on his desk, then said, “Would that be Mrs. Eula Williams, 409 Rockport Avenue?”

“Yes, that’s her.”

The sergeant looked over his glasses down at Richie. “And this is the boy who shot her?”

“In self-defense, yes. She goes crazy when she gets mad. She was going to hit him with a bat. She tried to.”

The sergeant nodded. “I don’t think you’ll have any problem convincing anyone about what happened. When the police arrived along with the EMTs in response to the 911 call, she started yelling at them, then picked up a bat. She broke one of the officers' arms before they knew what was happening. Then she went after the other one. They had to use a taser on her. Even then, it took both the EMTs and both cops to subdue her. They finally got the cuffs on her, but she was practically frothing at the mouth by then. They said one of the bedrooms looked like a war zone. Just my opinion, but I don’t think there’s going to be any problem over your son’s involvement in this: if this boy was trying to save himself from her and she had that bat, shooting her was certainly appropriate. I’d have done the same thing myself!”

≈ ≈ 6 ≈ ≈

The following week Pastor Franks ranted a strong sermon about the evils of homosexuality again, how homosexuals were contaminating the nation’s youth, and how everyone must be vigilant and aggressive in discovering and saving young people beguiled by those sinful, depraved, disgusting sexual urges. During his sermon, he publicly denounced Richie Williams by name to the congregation, and he spoke about how the evil homosexual urges the boy had led him into violence.

There was murmuring from the congregation when his sermon was finished. The people attending that church knew Richie. They’d watched him grow up. When Pastor Franks returned to his office, the four-man church elder’s council was there to greet him.

“Gentlemen!” He greeted them with a smile on his face and pride in his heart. He’d delivered a beautiful and moving sermon and was still feeling the glory of his achievement.

“Pastor,” said the oldest member of the council, his voice somber, “we’ve had a very alarming call. We’ve learned that Richie Williams was in to see you, told you things in confidence, and that you then promptly broke his trust. We understand he was almost killed because of that. Then, today, you named him in church. You outed a young boy, a minor, with no thought to the consequences this might have for him.”

Pastor Franks turned to hang up his robe. He had no worries here. What he’d done was thoroughly justified. Besides, these were old men. They were raised as he’d been raised. They understood that homosexuality couldn’t be allowed to flourish, and certainly not in their, well, in his church.

He turned around to explain this and was preempted. “We want a pastor who has love and compassion. Christian virtues. You have neither and cannot be trusted. We’ll have your resignation today. Without it, we’ll fire you. And I’d recommend against using us as a reference. What we’d say wouldn’t be of help to you. I just hope we can ameliorate the damage you’ve done here.”

≈ ≈ 7 ≈ ≈

It was two months later. Rich was living with his father. His mother was in jail awaiting trial on multiple charges.

He had a part-time job working with his dad. When school was back in session, he was going to try to continue working, but for some odd reason, his dad seemed to think his schoolwork would be more important than helping out. Rich was still trying to think of good arguments to refute that.

He and his father lived in a better part of town now than where Rich had been living, and he was making friends. His life seemed so much better. The only problem was, even though he was no longer keeping it secret that he was gay, he still hadn’t found someone special. He had resigned himself to waiting till summer was over and then seeing what would happen at school.

Their apartment was close enough to where he was working that he could walk there in the morning. It was a glorious day, and he was in a happy mood, something that was normal for him now. The wind off the ocean still carried a chill, but he was used to that. He was sure anyone living in Maine was accustomed to the wind.

When he arrived at his dad’s shop, he stopped before entering, as he always did, to read the sign.

Robert’s* Coffee House

• Choice selection of coffees from around the world

• Large selection of teas from the Orient

• Finest Pastries

• Full Breakfast and Lunch menu

And featuring

• Our special French Toast with assorted flavorful syrups

*and son!

Rich always smiled when he saw it. The ‘and son!’ had been added at the bottom—obviously added, as the rest of the sign had bright yellow lettering on a midnight-blue background. The ‘and son!’ was in white, and the letters were larger than the rest, painted by hand. It made him proud to see. He’d told his dad that, and his dad had said it couldn’t have made him nearly as proud as he himself had been when he’d painted it on.

‘Rich’. He’d asked his dad to call him that now; he’d tried Rick, but liked the sound of Rich better. Both sounded better than Richie, which he considered a kid’s name. He’d be 15 in another couple of months. Not a kid any longer. Rich entered the restaurant, the bell on the door tinkling its cheery greeting.

“Hey, Rich,” called his dad who was working at the counter, laying out set-ups for the lunch crowd.

“Hey, Dad,” he called back, shrugging out of his jacket. He’d put it on out of habit. Summer had arrived, and it was warm enough that even here in Maine he didn’t really need it.

“Big morning?” he asked. Rich came in at 10:30 and worked the lunch shift. He’d told his dad he’d work the morning shift, the time when they were busiest, but his dad had been adamant: boys needed their sleep. He’d got the coffee shop up and running without him and would continue without him—for breakfast. Rich hadn’t fought too hard. He hated getting up early.

“Yeah, it seems to be getting better all the time. We had a few people waiting for tables this morning, and it wasn’t the first time.”

Rich grinned. “Maybe you should think of buying up the store next door, knocking down the wall and expanding.”

His dad kept setting out place settings as they talked. “Yeah, well, that’s for you to do when you buy me out, hotshot!” he laughed. “I think I’ll just concentrate on making some money doing what I like doing and leave the entrepreneurship to the next generation. Besides which, there’ll be your college to pay for in a couple or three years.”

Rich stopped where he was. “College?”

“Of course. You’ll be the first one in the family to go.” He grinned at Rich. “Your grades are great. Just keep them that way and you can pick wherever you want to go. You can be whatever you want to be, Rich.”

Rich shook his head in wonder. Life was so different now. In only a few months, he’d gone from being a scared little boy living with a tyrannical and unbalanced primal force of a mother to being a secure kid in a loving home with his supportive father. The change was so remarkable that he still sometimes reeled from the effects.

One of the changes was that he was now out. Pastor Franks had made sure of that. Rich was sure it was retribution for what had happened in his office. Rich hadn’t really planned that. He had gone to the church to hand the pastor the gun when he first arrived. But the man’s smug attitude had pissed him off. He’d wanted to scare the man, make him understand what he’d done and punish him for it.

And the pastor had been scared. And then vindictive. Afterwards, when Richie and his dad had left, the fear had turned into anger. Pastor Franks had taken his first opportunity to let his congregation know that Richie was gay.

Rich didn’t attend that church any longer, even though he’d heard Pastor Franks was no longer there. And he didn’t live in that neighborhood, either. But he would be returning to the same school. He wasn’t sure what would happen there but was encouraged by what he’d heard. His dad had already spoken to the new principal coming to Rich’s school, and he had been assured things would be better there now. According to the principal, all kids were going to feel safe at school. Furthermore, a gay support group was being created, along with a promise it would be active.

There were a few kids who’d attended the school who, in the past, had been troublemakers, but the worst had been expelled. The principal had told Mr. Williams that, in general, old attitudes were being replaced with new ones across the country. Fewer parents and churches were teaching kids hatred and intolerance these days. Because of this there was a growing trend where the current generation of kids for the most part accepted gay kids as just another variation on a theme, the theme of being a kid. He said schools today were vanguards in this change, and he himself was a great proponent of what was happening and would be helping their school move into the future.

Rich was happy being out. It was what he’d wanted. Now, maybe, perhaps, he might find someone. He was looking forward to going back to school at the end of the summer.

Before going to work, he stopped to look at the place his dad had built. He thought it was amazing. It wasn’t just another storefront for a quick cup of coffee. It was a spacious room that was bright and cheery, but it also was much more. It oozed class and charm. It had white tablecloths and a vase with two or three fresh flowers on each table. Hardwoods, waxed, polished and shining, gleamed throughout. Stainless-steel silverware was used, but it was top of the line and looked it. The glassware and plates were top grade, too.

There was a counter that ran along the back of the main room with the grill behind it; a kitchen was located in a separate room in the rear. The stools at the counter all had backs, and the seats were covered in dark-maroon leatherette. The counter itself was mahogany. Greenery hung in ceiling baskets and plants stood on the wooden partitions that gave many of the tables a feeling of privacy. The lighting was changeable, bright in the mornings, muted at lunch. When anyone walked in, their first impression was: wow! Yet the prices were the same as any other coffee shop. The food and service, however, well exceeded the norm, and the coffee was outstanding. His dad had told Rich that if you gave great service and great product for the money, customers would find you and keep coming back.

Rich was still putting on his apron when the bell over the door tinkled its merry greeting. A boy about his age came in. Rich had seen him before, although as he always sat at the counter they hadn’t spoken. Rich was responsible for waiting on the tables and bussing them so didn’t have much to do with the counter.

A few tables still needed set ups. The tables had been cleared and wiped down from breakfast but not yet reset. Rich got busy doing that. He had to adjust his bow tie a few times. He was sure he’d get used to it eventually, but his starched white shirt and black bow tie, complemented by his dark maroon apron, still had him sliding a finger under his collar and scratching his neck before the end of his three-hour shift.

He was stacking glasses from the dishwasher onto the shelf where they were kept when his father came into the kitchen. “Rich, could you work the counter for a while? We’re having clam chowder for lunch today and I still have some work to do on it.”

“Sure dad. We’re not busy yet, are we?”

“Nope. It’ll be easy. Just one customer.”

Rich set the last glass in place and, glancing in the mirror that hung just inside the kitchen next to the door to make sure his tie was straight and his hair in place, pushed through the door.

The restaurant was empty except for the boy at the counter, who looked up as Rich approached, then quickly looked down again. Rich set a glass of water with ice and a thin slice of lemon next to him and said, “Welcome to Robert’s Coffee House.” He handed the boy a menu, saying, “Breakfast is on the front, lunch on the back. I’ve seen you here before, so you know that.” He grinned at him, but the boy wasn’t looking up. “Have you decided what you’d like today, or would you like a few minutes? There’s no rush. We’re really not too busy right now.”

The boy glanced around, and Rich laughed.

The boy moved his eyes from the room to Rich, then moved them ever so slightly so he was looking past Rich instead of right at him. He mumbled an order nervously, cheeseburger and fries and a Coke, then looked down at the counter. Rich told him it would be up soon, then walked back into the kitchen.

“Cheeseburger and fries, Dad,” he said.

He dad looked up from the cutting board where he was working. “Why don’t you do it, and I’ll keep going with the soup. I want to finish mincing this garlic now that I’ve started, and the sooner it’s in the pot, the better.”

“Sure, dad. Hey, that customer? I’ve seen him come in before, but this is the first time I’ve spoken to him. I can’t believe how shy he is!”

His father looked up at him briefly, then picked up his knife again. “I’m not sure that’s entirely shyness.”

“Whatta you mean?”

His dad paused chopping garlic and looked back over at Rich, a smile on his face. “He comes in three or four days a week. You’ve seen him. He always sits at the counter. And he watches you. All the time. Whenever you start to turn toward the counter, he shifts his eyes, but pretty quickly he’s back looking at you again. I think you’ve got yourself a genuine, class A, through-and-through admirer. 'Course, I don’t blame him. In that outfit you’re wearing, you’re cute as a chipmunk.”

“Aw, Dad!” Rich didn’t want to hear that from his dad, but then again, maybe he did. But he didn’t want to be cute. Handsome, well, that was OK, but not cute. Cute was for little kids.

Rich looked at his father grinning at him, then shook his head. He pushed through the swinging door back to where the boy was sitting at the counter. Without looking at him, Rich grabbed a patty out of the refrigerator and slapped it on the grill. Then he turned.

“How would you like this cooked, sir?” he asked the boy, his eyes twinkling playfully. The boy, who’d been intently watching him, seemed caught unawares.

The boy’s eyes drifted away from Rich, and he said, “‘Sir?’” And then, “Oh, I, uh, I mean, medium, I guess.” Rich could see a blush infuse the boy’s cheeks.

Wow! This kid was either painfully shy, or he had it bad. And he was really cute. Well, OK, maybe ‘cute’ did apply, sometimes. Because it sure described this boy: short, straw-blond hair, rosy patches on his cheeks, thin body, handsome features—but he was white! Rich had never thought about dating a white boy. In his fantasies, the boy had never been white. But . . . why not? The kid was cute, and if the boy liked him, well... why not?

Rich flipped the burger and set a bun on the grill to brown. “What kind of cheese do you want, sir?” he asked, only partly repressing a grin. “We have cheddar, jack, Swiss, provolone and blue.”

The kid looked up, and their eyes met. As the kid started to drop his, Rich said, “Hey!”

The kid raised his eyes again. Rich let him see his grin, then said, “You don’t need to look away. You’re cute.” Trying to evoke something other than shyness, trying to get him talking.

The kid looked away really fast, but then slowly, as though he had to force himself, turned back, and a shy, tentative smile formed on his lips. “You are, too,” he said, very softly, and then his eyes, his bright blue eyes, opened wide in surprise, shocked at his own audacity, wondering at his courage, and his blush grew more obvious.

It was Rich’s turn to beam a full, delighted grin. He might not want to be called cute by his father, but from this kid? That was OK. No, that was good. Better than good.

Rich wanted the conversation to continue and was wondering how to manage that without the kid freezing up. Exchanging names—that would be a good place to start. Rich opened his mouth and then froze. The odor of burning meat and bread rose from the grill.

“Oh, crap!” he said and quickly scraped everything off the grill and into the trash. He turned to look at the boy and found the kid was laughing. Rich rolled his eyes at him in a plea for sympathy, and then, with little thought, threw two patties on the grill. He was hungry too, so, why not? It would be easier to talk over lunch if the kid was really that shy.

He dumped some fries in the basket, set it in the hot oil, then wiped his hands on the towel hanging by the grill and, suddenly feeling very good about himself, moved down the counter to where they could talk.

Rich was surprised by how it went. Shawn, which was the boy’s name, was certainly shy, but when they talked, the shyness seemed to drop away and conversing was surprisingly easy. Rich found himself fascinated by Shawn’s blue eyes. As they talked, more and more frequently Shawn raised his eyes, allowing Rich to look into them. Shawn couldn't seem to get enough of Rich’s dark and expressive brown eyes, either.

Two more burgers and buns had to be thrown away when they began smoking, but no one seemed to care.

The End

Photo by Raphael Brasileiro at Pexels.com