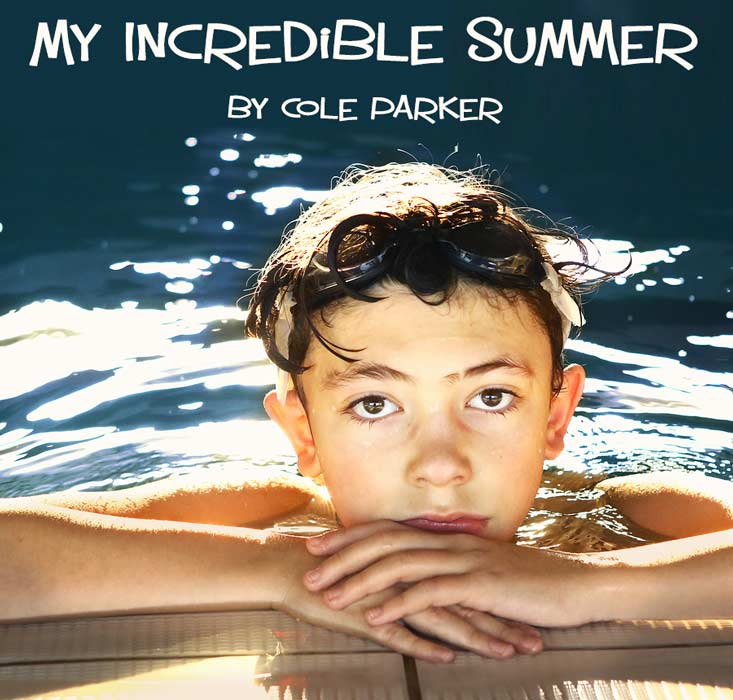

I want to tell you about my summer. It changed my life.

I guess as good a place to start as any would be what happened the first day of summer vacation. It was sort of exciting; a family was moving into the Gorsuch house just down the street. The Gorsuchs only moved out a few days ago. Dad had told me the housing market in the entire LA area was hot right now, and almost anything that went on sale was gobbled up quickly.

I watch as the moving van is being unloaded. Furniture and boxes are being hauled into the house. I guess because new people are moving in, we’ll be calling it something other than the Gorsuch house now.

I don’t know anything about the new people. No one I asked does. Of course, as I talked just to my family, it’s probably truer to say that no one in my family knows anything about them.

Not that we would. My parents didn’t socialize much with our neighbors. Or at all, really. Waving at them as they drove by would be about the extent of it. My mom was an attorney. She worked for a large firm and mostly did copyright-infringement work. That was a big deal in LA because of all the money in the movie industry and lawsuits over people stealing other people’s ideas for books and TV shows and movies and such. She was almost a partner; she expected that would happen in the next few years. That being the case, she worked long hours. Most almost-partners did that, looking to get a leg up on their competition. But a lot of the partners did, too, so maybe when the promotion occurred we still wouldn’t see much of her. We were used to that by now.

My dad was a banker and near the top where he worked. He also worked long hours, and his fervent wish was to become a vice president before he was 50. So, we didn’t see all that much of him, either.

Who is this we I keep mentioning? That was the rest of the family. There were the ’rents, then me and Joy. We are twins. Thirteen and left basically parentless for the past two years as my parents had decided we were mature enough to handle that abandonment. They, of course, didn’t use that term. We did. To us it was a de facto semi-abandonment. Though we think that decision was much more about them than us. They loved their careers. ’Nuff said.

They could have hired a nanny or a full-time sitter for us. They both raked in the dough, and we lived in a posh area of Arcadia. But they said because of that, because of the quality of the area and the fact our neighborhood was gated and had basically no crime at all, we’d be safe without needing an extra adult around all the time to see after us.

We weren’t entirely alone. We did have a maid service that came three times a week for a couple of hours. They weren’t there to look after us, though. Both mom and dad had the occasional need to entertain at home, and they wanted the place immaculate for those times. Image was everything in LA. This of course meant two thirteen-year-olds had to live in a house that was immaculate. You ever been thirteen and not make any messes? You ever try to be personally immaculate at that age? Yeah, like that. It was a good thing we had our own wing in the house that guests never entered. That part of the house was no more immaculate than I was.

We stayed out of the living and dining rooms and Dad’s study and Mom’s workroom. Yeah, they both had their own den or study or whatever you want to call those rooms. I did say the house was pretty large, didn’t I? But we avoided most of the downstairs. My room, however, was my room, and if it was messy, they could yell all they wanted. It was my room to keep as I wanted. If they had guests, the guests would have no reason to come upstairs into our part of the house, and anyway, I had a door on my room, and I could and did shut it. Even when they were home, however, they didn’t say anything about the shambles I called home. Live and let live, I guess.

Joy had her room as well. She wasn’t as messy as I was. But then, she wasn’t a thirteen-year-old boy, either. I’ve heard that some girls are just as messy as boys. Maybe so, but not in our house. I mean, she wasn’t a neat freak, but she threw dirty clothes into her hamper and sometimes even made her bed. Go figure! She said she liked walking into her room and seeing how nice it looked: orderly, clean, the bed made. I told her I liked to be able to plop down on the bed at night without bothering to have to pull the spread back. Saved a lot of time.

About the only thing we did downstairs was go into the kitchen. There was a breakfast nook, and we ate there. What did we eat? Well, Mom wasn’t a cook. She was an attorney. Not a cook. We’d been made very clear on that. Not a laundress, either; one of the maids did that task once a week. But about cooking . . . We were thirteen; how many kids our age are good cooks? Some, I guess. Joy had no interest in cooking, so that avenue was closed, too. Actually, I was taking a stab at learning how. Cooking seemed like an art form to me, an artistic craft at least, and I was into things like that, so I was learning. There were lots of videos on YouTube that showed how to make things, and I could lay my laptop on the counter and work along with the video, and some of the stuff I made was actually edible. But I only did this when I was in the mood, not every day, and I did like to eat every day. I didn’t want to make a career of cooking, just simply to know how so I could make things when the urge to be creative hit.

We needed both breakfast and dinner every day, and lunch, too, on the weekends and during the summer when we weren’t in school, where food was provided, and I didn’t want to spend that much time in the kitchen. So, to satisfy our feeding needs, Mom bought prepared meals from a couple of restaurants in town and had them delivered. We had two freezers, one for lunches, one for dinners—both full. All we had to do was heat up the meals up. That was easy enough to do as heating times and temperatures were taped on each dish. We didn’t starve and ate pretty well.

What did I do with my time? I’d love to say I spent it hanging with my friends, but I didn’t really have many of those. I guess you could say our house was where some of the rich people in town lived, and not many of them had kids our age. Maybe that’s why they were rich.

I could ride my bike around all the streets in our enclave, and I did, but I never saw any middle-school kids outside. I knew kids at school, but somehow I never made any close friendships there. Probably my fault. I wasn’t really antisocial but did have a problem. At least that’s what Joy said. She was very social; she did have friends, and sometimes even had them at the house. They were girl friends, though, and do you know what middle-school girls are like? You’re lucky if you don’t! They’re cliquish and gossipy and always trying to outdo each other and have the upper hand. They talk constantly about boys, and they’re really icky.

But I was about to talk about my problem, why I didn’t have friends. At least Joy said it was my problem, the friendless bit. “Jody,” she’d say, “you need to get out of your head. You’re constantly daydreaming, constantly thinking about things and not living in the real world. If another kid talks to you, you either ignore them or barely say two words. You have to make an effort with people.”

She doesn’t like it that I’m alone most of the time. I don’t mind. I don’t really consider it a problem. I’m fine. I use my time to think, to read, to imagine, to fantasize. And I do get out some. I ride my bike. I swim in our pool. And sometimes I even get Joy to do these things with me.

Joy and I are close. We’re not identical twins, but people think we are when they meet us. They don’t seem to realize that monozygotic twins are always the same sex. We’re dizygotic. Hey, I already told you I read a lot. Give me a break!

Some of that reading has been about twins. Well, why wouldn’t it have been?

Anyway, we’re close. Not all twins are. Some fight a lot. I’ve read that the ones who do are usually trying to establish their own identities. Joy and I have never done that. We’re fine together. She does have a more diverse social life than I do, but that doesn’t bother me at all. I like the way I am.

So why does she think I have a problem? That’s kinda funny, in an odd sort of way. See, like a lot of twins, we have this telepathic link. It was really strong when we were younger, and while it’s less strong now, it’s still there. When younger, we could usually tell what the other was thinking. Now, we can still do that, but it’s more that we feel the emotions the other is feeling, especially when they’re strong. But then, if the thoughts we’re having are fraught with emotion, they’re easy to read as well. And Joy can do it better than I can, especially the feeling-emotions part.

My problem? Gee, I’m getting there. Hold your horses.

But, see, this is what I’m like. I go on diversions a lot, get sidetracked, let one thought lead to another and take a moment or two, perhaps even longer, getting back to where I was originally going, but I do get there. I’m not stupid. Maybe the opposite of that. Maybe that’s my problem! It’s not the one Joy complains about, though. What Joy’s problem with me is this: she says my thoughts and feelings are so wild, so scattered, so tumble-about messy, that she has a hard time focusing on her own thoughts; that my random scattershot thinking interferes with her concentration. My view of it? I think she just enjoys yanking my chain.

What I find ironic is that she says this is my problem! Hah! It really is hers. Anyone can see that. Or could if they knew about it. This is private stuff we have. We have quite a bit of private stuff. We’re twins, even if dizygotic ones. We spent nine months in a small womb, pressed together so that we couldn’t tell where one started and one ended. Is it surprising we still feel a great deal of comfort being together after all that?

So, no one really knew how much telepathy, how much sharing of feelings, we had. We didn’t let on. No one’s business but ours! Oh, we’d tried to tell our parents about it when we were young, but they pooh-poohed the idea. I don’t think my mom ever did get it. My dad? Well, maybe. Once, years earlier.

As is often the case, this ability of ours isn’t quite as strong now as it had been when we were younger. I already said this, I know, but I don’t know what your attention span is, and it bears repeating. Puberty is supposed to weaken that link, and that was probably what was doing it. We’d both learned how to block the other out of our heads, though neither of us had much reason to do that. We didn’t have any secrets from each other. We’d spent a lifetime sharing who we were. No reason to change. No reason to be embarrassed about anything.

OK, I know what you’re thinking. Maybe I can read your mind, too! You’re thinking boys my age do things that they don’t want anyone else to know about, not even twin sisters. And when boys are doing those things, their brain waves and feelings tend to be over the top, spewing out here and there and everywhere to anyone who’s capable of receiving and interpreting them.

So . . . Well, I’ll discuss this in greater detail later. I was talking about the people down the street moving in and my watching what was going on. The reason I was so interested was because one of the first things that came out of that moving van was a bicycle. One just like mine. Same size, same 21-speed gearing. Except mine was a trail bike, and this one had those really skinny tires. I guess you’d call it a racing bike. But it looked to me—it was easy for me to imagine—that it was a kid’s bike. Could there be a boy my age moving in down the street? I’d like that. Not that I expected, even if it were true, that I’d suddenly have a best friend. Most boys my age were quite athletic, and I wasn’t. Most boys were starting to feel intrepid and adventurous, and I wasn’t. Riding my bike and swimming were about the only physical things I did. It took very little actual courage to do them. So, the chances were, if the bike was a boy’s and he was thirteen, give or take, we’d be more acquaintances than friends. Still, though, there was a chance. And having someone to hang with would get me out of my head a little and give my fantasies some downtime.

School had just let out. It was the end of May. Although summer vacation had just begun, I was already lolling around the house bored. Joy had been with me some, but she did have friends and told me she’d be having them over this summer, and she was planning to go to their houses, so sometimes I’d be alone.

I liked being alone, really. No one to disturb my thoughts that way. Her thoughts and feelings didn’t bother me as much as mine did her. Maybe it was just that she was more nosy than I was, poking around in my head whenever; doesn’t that sound like a girly thing, being nosy? But I digress. Her thoughts tended to run to the practical; I thought about transitory, elliptical, fanciful things. And sex, of course. She didn’t think much about that. Perhaps that was one reason she wanted me to have friends, to be out of the house more. I suppose she could have chosen to block those images she borrowed from me, but the more we blocked each other, the more we weakened our bond. We both liked being able to tune in on each other.

I remember one time rather vividly that made a big difference for me. It was before we moved into this house. The old neighborhood we’d been in was more middle class. Both our parents were climbing the corporate ladders but hadn’t even reached the middle rungs at that point. There were more kids around in that neighborhood, of course, but I still tended to be a loner, wrapped up in my thoughts, isolated, really, but intentionally so.

There was a large vacant lot next to our house full of bushes and brambles and such. I was six, I think, or was I seven? Probably six. I was small enough to be able to make my way through the wild growth that covered that field without being seen. I liked it. I could imagine myself on adventures there. Because many of the bushes were taller than I was—hence the not-able-to-be-seen part—my sight lines were limited.

The day I’m talking about, a Sunday, I discovered something new. There was a large patch of raspberry bushes in that field I hadn’t ever found before. You know how raspberries grow, don’t you? On pricker bushes, that’s how. Those bushes are all brambly, thorny buggers, but when you have really ripe, sweet, juicy berries, the really sharp prickers take second place. I started picking and eating raspberries, hardly getting pricked at all. After a couple of mouthfuls, I decided to take a bunch of the berries home for my family. So, I pulled out the bottom of my tee shirt, pulled it up some to create a sort of basket, held it with one hand and used the other to pick berries and drop them in the basket.

I’d been working for some time and had lots of berries picked when I heard someone coming. I looked up, and there were two boys. They were both older than I was, maybe a year or so, and they were bigger.

“What’s this?” the bigger one said, seeing me. “Hey, you’re stealing our berries!”

I might only have been six, but I also knew the vacant lot didn’t belong to this boy—or his friend. I also saw the one who spoke look at his friend and grin. I knew he was lying.

“No I’m not,” I said, but my voice betrayed me. I meant it to sound strong and intimidating. It sounded instead like I felt: scared. I was small and alone and they were large and menacing.

“You have our berries. Nice of you to have already picked them for us. We don’t have to worry about the prickers this way. Now, give ’em to us. Tommy, do with your shirt like he did. He can dump the ones he has in.”

“No!” I said, still sounding scared, but also upset. I’d gone to a lot of trouble picking those berries, I’d been expecting my mom to be really happy with me when I brought them home, and now these two were planning to take them away, and that wouldn’t be fair.

Young boys are very big on what’s fair and what’s not.

The kid who’d spoken looked at me and frowned. Then he turned to his friend. “If we just take them away from him, he’ll spill most of them and we’ll have to pick them all up. They’ll be all dirty and we’ll get juice all over our hands. Whata ya think? How should we go about getting ’em?”

Evidently the other kid was the brains of the outfit. He looked at me, looked at the bushes, and smiled. “Look, kid,” he said, and I could see the smile wasn’t a happy one. It was like the evil ones I saw on TV cartoons that sometimes gave me nightmares. I had lots of nightmares from stories, TV, movies, all sorts of things. Mom said I was too sensitive.

He kept smiling. “Give us those berries and don’t spill any, or you know what? We’re going to pick you up and throw you into the pricker bushes.”

I had too good an imagination. Way too good. I could visualize them doing that, and I just knew how much it would hurt. I could even imagine getting prickers in my eyes and being blind from then on. I could see myself trying to wriggle out and just end up getting deeper and deeper into the prickers. They’d laugh as I screamed, then mosey off, and I’d be unable to get out. I’d die in that bush. Die hurting every time I moved, getting stabbed by those prickers.

I thought all this, saw it all clearly, and I started crying. The two boys didn’t care about that. They came toward me, ready to take those berries or maybe pick me up and throw me in the bushes. One or the other; maybe both.

I froze. I couldn’t run; I was too scared. And then an amazing thing happened. “Jody!” I heard myself being called, and the calling was coming from my dad. The two boys stopped in their tracks, and I thawed out enough to holler, “I’m here. I’m here!”

My dad and Joy came through the bushes, and the two boys ran away. “See,” Joy said to our dad, watching the boys flee, “I told you he was in trouble and needed you.”

My dad looked at the two of us. He’d never believed we could read each other’s minds, feel each other’s feelings. From then on, I think he did—at least a little. He probably never knew or understood just how well we could do that, but this incident proved to him that we had some capacity along that line. After all, there was not doubt that Joy’s ability to read the fear I’d been feeling had saved me.

And those berries on vanilla ice cream that night were about the best thing I’d ever eaten.

But I don’t want to get sidetracked talking about Joy’s and my sensitivity to each other’s thoughts and emotions, and I already said I’d leave talking about sex till later, so I need to get back to where I started. I was talking about the movers. You see how sidetracked I get? That’s what I’m talking about. My mind goes helter-skelter all the time. Drives Joy crazy!

I kind of like that.

So, I decide to go outside and down the street and maybe meet the new people. See if they have a kid, maybe a boy, maybe my age, and maybe friendly.

Perhaps I should say something about our neighborhood. There were about 15, perhaps 20 streets behind those gates, I guess. I’ve never counted them. It was hard to do that because the streets were all curvy and had side streets running off them, with others running off those. There were numerous cul-de-sacs, some of them very short streets and some long. It was hilly, but most of the hills were long and gentle rather than short and steep.

The houses for the most part were quite large. Now you’d think, if you had a large house, it would be so you’d have room for lots of kids. Yet, I’ve already said that wasn’t the case. Or at least I hadn’t seen any young teens like me riding around. Maybe there were some, or even a lot, but if so, they stayed inside watching TV or playing on their phones all day.

You might think I’d know if there were kids because we’d all ride the school bus together. Wrong! Joy and I rode our bikes to school, or if it was raining, we took a taxi. Now that sounds extreme, I know, but we lived only a mile from the school, it almost never rains much in LA, and I liked the freedom I had riding my bike instead of waiting for a bus and then joining in with all the cretins who rode it every day. I hope you don’t get the idea from this that I’m aloof, or, if not that, that I’m not very courageous; you might not be totally wrong about that second part, but aloof is about the last thing I was. Anyway, this is meant to be a discourse about the bus, not my mettle. The bus came by well before I had to leave for school on my bike, and it arrived back from school in our area well after I got home on my bike. Those were the reasons why I preferred my bike. I also appreciated the fact bullies couldn’t have their way with me if I wasn’t within their grasp. Buses aren’t good if there are bullies on them. Boys who aren’t athletic or brave make great targets, and those buses are confined spaces.

But that’s beside the point. I was talking about houses. Big ones. Like ours. Ours was a little over 4,000 square feet. Well, actually more than a little over. It was closer to 4,500 than 4,000. But 4,500 sounds pretentious, and our house wasn’t that, at least not to me. It was just our house. The lawn was tended to by guys who came once a week and mowed and edged and raked and did all the stuff those guys do. Another two guys, gardeners, came every other week to tend to the gardens in the back yard. We also had a pool man who came weekly to check the chemical levels and the filter and heater and all. They kept the water sparkling and clear and warm year around. I guess if you count the maid service, we had quite a big staff helping us out. I was sure glad Dad thought I was as incompetent as he did or maybe I’d have had to do a lot of that.

The other houses in the enclave varied a bit in size. Some were a bit smaller, some a bit larger, but all were roughly similar size-wise. Most were two stories, like ours. One thing really nice about our house was that the back yard was quite private. Because building lots tend to be small in LA, most single-family houses had fences or walls between them and their neighbors. Walls were more common than fences, and most houses had cinder-block or slumpstone-block walls high enough to be difficult or impossible to see over without using a ladder. When someone lives cheek-by-jowl crammed next to people on all sides, he gets his separation and what little privacy he can when and how he can. Walls were popular.

We were lucky. Our house had a much larger back yard than most because we were on the back end of a cul-de-sac, and Dad had been smart enough or affluent enough to buy two lots and put our house in the middle of the two. We had room on both sides, and with our walls and bushes and trees, we had complete privacy from our neighbors on both sides. We also had a deeper back yard than most because of the way the land was shaped in our cul-de-sac. There was a hill behind us, and the house behind us was farther back than most.

The fly in the ointment is that Dad didn’t have the foresight or the money to buy the lot behind us, too. Or maybe, not being a kid like I was, complete privacy wasn’t that important to him. I mean, gee, all he’d ever do out back was sit in his shorts or bathing suit and read the Wall Street Journal. On the other hand, when I was alone or only with Joy, I liked to take advantage of all that privacy and swim as God intended boys to swim. That’s where that ointmented fly came in.

There was a house directly behind ours. As I said, it was a ways away, but still, its upper story overlooked our property. That was the bad news. The good news was, I was pretty sure that house was unoccupied. Let me explain. There are a lot of rich people in LA, and property values are always going up. I know, that isn’t possible forever. But try to buy a house in LA and decide they’re too expensive and that you’ll wait a year and buy one when a down market has hit and prices have fallen or are falling. Just try. You’ll see that the impossibility of prices always rising is kicking you in the nuts. House prices always go up here. So, because everyone is aware of that, some people—really rich people—buy houses just as an investment, planning to hold them for a time and then sell them for a profit.

Some of those people, of course, rent the houses out after buying them. But some don’t want to deal with tenants and inspections and damage and evictions and all that. They just let the houses they buy on spec sit empty, feeling their profit will more than cover their expenses. I thought that might be what was up with the house behind us. I’d never seen a light in any of the windows at night, and when I’d ridden my bike past it during the day, it had that dismal, vacant look unoccupied houses have. So, being brave as I am—well, in some things—I’d started swimming au naturel this summer. So far, I’d heard no screaming from behind us, and no SWAT teams with drawn weaponry had shown up to haul me away so as to protect the city’s modesty.

I especially liked swimming at night when the air was still, the water black and warm. Nature seemed to have a way of wrapping itself around a small, naked boy. Too, if there was anyone in that house behind us, I didn’t have to worry about being seen at night. Now and then I glanced that way just to be sure. Once I’d seen a glint in the window upstairs, but I was sure it was the moon reflecting off the glass. And that had only been once.

What does this have to do with visiting our new moving-in neighbors? Nothing. Other than saying going three houses down was farther than you might expect because of the size of the houses. Maybe I could have just said that.

So, I get on my bike and ride down to their house, stop and stand and watch. So far, only the moving-van guys seemed to be there, emptying the truck, taking furniture and some boxes inside, stacking some stuff in the garage. The overhead garage door is open to make that easier, and I can see the bike I’d witnessed coming off the truck now leaning against one wall.

Then a door from the house into the garage opens, and a girl steps out. She looks around, then at me. I look back. My heart speeds up just a little. Not out of sexual excitement. Yeah, she’s pretty, but that’s not the excitement I feel. What I feel is due to the fact that she has come out and is looking at me, and that means she’ll probably come over to talk to me. That’s how most people behave. Most people are friendly. But it’s difficult for me, meeting people, chatting with them. I never know what to say. I always feel they’re judging me, finding something missing in me. But mostly it’s because they’ll say something and not give me time to think about it. I’m supposed to respond when someone speaks to me. That’s how things usually work. But my mind seems to work differently. My mind tends to grab onto what the person says and then think about it, consider it, look into what it might mean, maybe even go off on a tangent because of something they said or a word they used, and I get so distracted doing all that that suddenly the person will be wondering if I’m either deaf or stupid or autistic or deranged. I’m not. I just don’t do idle chatter very well with people I don’t know yet. Or people I do know. So I get worried in a situation like this. I know I’m going to look bad.

OK, so why did I come over here, knowing all this? Good question.

It’s probably because I was hoping a boy would come out, not a girl, that he might be a pipsqueak like me, he might be shy, maybe even a little younger than I am, and that maybe I could get through meeting him without looking like a first-rate goober.

Not going to happen.

She sort of smiles at me and sort of doesn’t. She does approach me. She doesn’t speak, though. It’s her house, so her turn to speak, to introduce herself, to ask me about me and the neighborhood. Oh, yes, I know how it’s supposed to work. I’m just crapola at it. But she doesn’t speak, so now I know what to do. Unlikely, but I do.

She just comes up and stares at me, obviously expecting me to speak first. She is very pretty, but too old for me. I guess she’s already in high school, and I have one more year of middle school to finish. The pause gets pregnant enough for a baby to be delivered, and I blurt out, “Hi. I’m Jody. I live up the street. Just wanted to welcome you.”

It all comes out rather quickly, and I only meet her eyes briefly at the beginning and the end. It’s her turn now, and I can wait till the baby’s ready for preschool if that’s how long it takes her to say something.

“Missy,” she says, and yawns. “You’re young, aren’t you? Any older kids around here. Any cute boys?”

I note she doesn’t say any ‘other’ cute boys, so I guess I don’t qualify for that, although in my opinion I look OK. I realize I’m getting sidetracked and answer as quickly as possible. “Nope.”

“Oh,” she says, then turns around and walks back into the house. Even her stride is haughty. Maybe living in this neighborhood makes being standoffish not that surprising, though neither Joy or I is. In the doorway, she has to turn sideways because a boy is walking out. “Watch it, Ken,” she says, annoyed when he bumps her. He ignores her.

He’s younger than she is, I can see that right off. Probably my age. But bigger than I am. I’m real slender. My legs and arms are appropriate to my slenderness: they look something like the PVC water lines I’ve seen lawn guys installing for sprinkler systems. This guy looks like he does weights or something. His body is sturdy, his arms and legs muscular, not all that common in guys who are thirteen. He’s wearing a pair of shorts, tight short shorts that come halfway up his legs between his knees and crotch and nothing else but sandals. He has a thin sheen of sweat on his torso. He was probably unpacking inside or setting up his weight bench or doing that other thing I referred to earlier that boys do. All those could account for the sweat.

See how my mind works? It’s all over the place. By the time I snap out of it, he’s standing in front of me. So close I can smell him. He smells like a young teen boy who’s been sweating, and something else, too. Probably some scented body wash. He’s staring at me.

“Who’re you?” he asks. He asks it rather aggressively, like maybe I shouldn’t be here in his space, like maybe I’m interloping.

“Jody,” I say.

“Jody? Hah! That’s a girl’s name!” There’s almost a sneer in his voice now, no friendliness at all. He doesn’t tell me his name, but I know what it is now. He runs his eyes up and down my body, lingering on my arms. I take the time to do the same. The most noticeable thing to me is that the shorts have a bulge in them, right where you might expect one to be. I don’t have any bulge in my shorts, and they come down to my knees. His makes me think he really might have been doing that thing that can make a boy both sweat and bulge. Of course, it is a warm day, so maybe it’s not from that.

He’s still looking me over, so I think I might say something to distract him. “I just came over to say hi to you guys. Welcome you. I live up there.” I point to our house.

“You going into eighth grade this year like me?” he asks.

“Yeah,” I say, trying to keep my mind on what he says and not the bulge. “You’ll like the school. It’s nice.”

“Huh,” he says, wrinkling his face like he smelled something that’s off a bit. “I go to Hillcrest. It’s a private school. I’m on the soccer team, a forward. Top scorer. You don’t play anything, do you? You sure don’t look like it.” He says this with that sneer, too, and looks back at my arms and legs.

How should I answer? I hate being on the defensive, and that’s what he’s doing, questioning first my name and then my athleticism. I figure out what to say, though. I’m proud of myself! “I swim.”

He looks disgusted. “Bunch of fags on the swim team. You a fag? We don’t tolerate fags at my school.”

My heart starts beating harder. It sped up when he came out of the house, faster than when Missy was there. Now if it gets any faster, it’ll be setting a land-speed record. I fumble for words, and then I hear, “Jody, come here. I need you right now.” Joy is calling from our front yard.

“Got to go,” I say and push off on my bike. He watches me all the way home, or is he just looking at Joy? I don’t know, but when I look back, there he is, staring. I realize he never did tell me his name, though I did hear say it—Ken. I also realize this is another boy that I’ll never be friends with. I don’t feel bad at all about that.

I thanked Joy when I got home. She just smiled at me. Then I went swimming. I needed to calm down, and swimming was the best way I had to accomplish that. Riding my bike worked, too, but what if Ken saw me and rode out to join me, to make sure I wasn’t gay, and to knock me off mine if I were? I was safe swimming.

I walk outside and strip. It always felt funny doing that in broad daylight, but I am still upset, and this takes my mind off my confrontation, and I ignore the feeling. I do glance up at the house behind us. It is quite a ways back, maybe 50, 60 yards. Our back yard is deep and has fancy gardens and trellises and decorative bushes artistically arranged. There are tiny lights on them and sometimes my parents entertain back there at night, and it’s really beautiful then. There is a slumpstone block wall at the very back of the property. It’s over six feet tall, and I can’t see over it. I can’t even see over it into the back yard of the house behind us from my upstairs bedroom window because of the hill.

Glancing up showed me the same thing it always did. The windows I could see were black. I thought there probably were blinds or curtains inside covering them because they always looked black. I didn’t see anyone or any movement. I decided that if anyone—if there was anyone there—wanted to see me naked badly enough, as long as I wasn’t aware of it, well, so what? Besides, most of the time I was in the water and they’d only be able to see the backside of me when it was above water. Could my backside be all that interesting? I couldn’t imagine how.

I was sort of hoping Joy would come out and join me, but she didn’t. While I was swimming, I looked for her in my mind and found her upstairs reading. She liked to read, just as I did, but she liked romances, YA romances, and I liked Sci-Fi and fantasy. Seeing what she was reading didn’t interest me at all, and I moved on. I swam until I was tired, hoping that would help me sleep that night and forget about Ken.

I couldn’t help but eventually let my mind fantasize about my earlier meeting with the boy. All sorts of situations arose in my head; none of them ended well. That was one problem with an active mind. Sometimes you ended up more depressed or upset than when you started thinking. I knew this wouldn’t bode well for tonight.

I read when I got in bed, just like always, this time after pulling out a humorous Sci-Fi book I’d enjoyed before, hoping it would elevate my mood. I knew it was hopeless, that even if it performed its magic, it wouldn’t make a difference later, but when I eventually shut off the light and dropped off, I did feel a lot better.

I woke up a while later sweating, with my heart thumping like it was trying to find a way out of my chest. Another nightmare. A new one this time. The boy I’d met, Ken, had been featured. He had me in his house lying on my back, arms and legs stretched out to the sides, tied up in that position. I was wearing what I’d worn when we’d met. He was lifting a barbell with heavy weights on it, up and down, up and down, holding it right over my head. His huge biceps were bulging; they weren’t the only thing. He had short shorts on, and they were even shorter than before. Sweat was dripping off his forehead and body onto my face. He began threatening to drop the barbell on me if I didn’t admit I was a fag. And he said when I did admit it, he’d drop it anyway because that was what should happen to fags. His sister was egging him on. She was naked for some reason that didn’t make sense to me. She was naked, he had shorts on that made his bulge much more pronounced, grossly pronounced. I woke up as the bar was beginning to slip out of his hands and he was laughing and saying, “Oops!”

I get up and walk to Joy’s room. I know what to expect. This happens a lot. My nightmares wake her up the same as they do me. I can just make her out in the dark sitting up in her bed. I see her nightwear on the floor; she’d taken it off when she knew I was coming. I am naked, too. I always sleep naked. She doesn’t unless I’m there.

I walk over to her bed and get in and roll onto my side, looking away from her. She is behind me and slides over so she’s got her front pressed against my back. She drapes one arm across my torso, the other hand rests on my shoulder. She holds me, we’re tightly together, and for the first time since the afternoon, I can relax. I suddenly feel whole, like there’s nothing missing from me. Like I’m not less than a full person.

When I wake up in the morning, she’s still holding me. I twist my head and see her eyes are open. I get up. I don’t have to thank her. She knows how I feel.

Most boys would be embarrassed, standing up naked in front of their sister in the state boys are in of a morning. I’m not. Embarrassed, I mean.

About the state I’m in? Yeah. Every morning. But she’s seen me naked all my life—and the other way around, too. There’s nothing sexual between us. We’re just two very close siblings, two halves of a whole, and while I need her comfort and strength many nights, she gets something out of it, too. She sleeps better when I’m in bed with her. I know that’s true. I read her as well as she reads me. We don’t lie to each other. No reason to. She knows what’s in my head, and I know what’s in hers. Lying would be silly and accomplish nothing. Not lying helps keep us close.

After breakfast, she comes swimming with me. She swims naked just like I do. I love the way the water feels, sliding along my body, and I feel the same pleasure coming to her. The house behind us is still, the windows black. The day is pleasant, warm but not hot.

I want to ride my bike afterwards, but I’m afraid Ken will come out. I don’t want to see him or him to see me. “Don’t be like that,” Joy says. “You can’t stay inside all summer because of him. He can’t do anything to you without getting in trouble. You want to ride, so go ride.”

Easy for her to say. She doesn’t have to worry about her head or chest being squashed by a ton or so of sweaty metal. But I go out and don’t see any activity at Ken’s house, so I get on my bike and take off. I know the streets here well. They’re deserted like always. Adults are at work by now, and if there are any kids, they’re all inside. Joy and I didn’t get up till late, which is usual when I have a nightmare, and then we swam after breakfast.

I ride for some time and end up passing by the house behind us. It’s as vacant looking as always. I ride on, and when I turn the next corner, I brake as quickly as I can. Halfway down the block, I see Ken. He’s on his bike, and he’s confronting another boy, one I’ve never seen before. Ken seems to be in the boy’s face. He’s looming over him, encroaching in his space. As I watch, Ken drops his bike and takes hold of the boy’s arm.

“I asked you a question, numbnuts. Where do you live? Are you deaf?” He’s talking loudly enough that I can hear him clearly from where I stand.

The boy is my size; Ken is significantly bigger. The boy looks Asian to me, with very black hair, sepia-colored skin and a face that is distinctly not built like mine. I can’t really see the expression on his face, but it appears to me that Ken is squeezing his arm hard enough to cause pain.

I have to do something to stop this! But what can I do? I’m the world’s biggest wimp. If I go up there and say something, Ken’ll probably attack me.

Then I figure it out. I take my phone out of my pocket and yell down the street. “Hey, Ken! Look—you’re on Candid Camera!” I start taking a video of him.

He lets go of the boy and turns to look in my direction, then yanks his bike off the ground, jumps on it and heads towards me. Shit! I doubt I can outride him, even with him a ways back from me. He can catch me, and then what? I’m too scared to consider it and fumble with my pedals trying to get started while turning around to ride away.

I’m very aware that he’ll catch me easily. Then I hear a voice. Ken hears it too and looks back. The Asian boy has a phone out, too, and is also apparently taking a video. He stops to yell at Ken. “You can catch one of us, but not both. One of us will have a video to show the police. You’ll be in deep shit!”

Ken stops. He looks back and forth between us. While he’s doing that, I take the opportunity to ride away. Looking back, I see the Asian boy walking down a driveway and alongside a house. Ken is still on his bike, not moving, obviously not knowing what to do. I laugh but don’t slow down. I ride as fast as I can home.

That evening, Joy and I swam. We did that a lot when the ’rents were gone. We didn’t talk in the water as I was thinking hard. She wasn’t listening to what was going on in my head, just enjoying the water and the night. The water felt even better at night for some reason. It was silky enough to feel erotic. With no light, the water was dark and felt mysterious. Even while I was thinking other things, I let it stimulate me. Joy laughed at me. She was in tune with me enough to know. She found the way I reacted to things silly. She was not nearly as sensitive as I was to whatever ambience we were experiencing.

Later, when we were sitting on the edge of the pool, enjoying the warm intermittent breeze as it kissed our wet skin, I caught a glint from the window of the house behind us. This was the second time it had happened. The other time there’d been a full moon, and I’d thought that was what had caused it. Tonight, the moon wasn’t up yet; the night was pitch black.

I didn’t say anything. I was quiet for a moment, immersed in the nighttime atmosphere, the peacefulness, the quietude. Then I got up and grabbed a towel. Joy did the same, aware of my mood; we got dressed without saying a word. She knew what I was going to do; she’d decided to do it with me.

We had a decent walk ahead of us, but the gentle night made it pleasant. I heard a dog bark in the distance, and occasionally a car purred past us. Some of our walk was uphill, but we were meandering rather than marching; we were in no hurry.

We finally arrived at the house that stood sentinel behind ours. I didn’t hesitate. I was never so timid when Joy was with me, and tonight, for some odd reason, I almost felt whole all by myself. I walked up and rang the doorbell. The house was dark, and I wondered if the electricity was turned off; maybe the doorbell wasn’t working. I didn’t hear anything when I pressed it, and no one was coming to the door.

There was an old-fashioned knocker mounted on the door, probably more as a door decoration than anything else, but I made use of it, rapping it loudly four times. That got the same response as the doorbell did. The house appeared dead.

So, I rap again, and this time call out, “I know you’re in there. We need to talk.” And I use the knocker again.

The door opens a crack. An eye peeps out. It’s the same height from the ground as mine. My two eyes and the one in the crack stare into each other from about three inches away. The inch of face surrounding the single eye seems sepia-colored, but in the dark it’s really hard to tell.

The eye stares at me. I’m sure it belongs to a boy. The boy doesn’t say anything.

“We need to talk,” I repeat. I’m surprised at how forceful I sound. Usually I make declarative statements that sound like questions. Apologetic questions. Joy said I have the least aggressive voice she’s ever heard.

More staring, then, “Why?”

“Because I want to know two things.” I’m not hesitant at all. “One, why you saved me today. And two, why you watch us in our pool.”

He doesn’t say anything but doesn’t close the door, either, so I wait. His move. Finally, he opens the door a little farther, as far as the chain on it allows, and I can see it’s the boy I thought it was, the Asian-looking boy Ken was bullying earlier today.

Finally, he speaks. “I can’t let you in.” His English is fine. Just like it was when he called out to Ken when he saw him starting to chase after me. He’d saved me. And then, he’d saved himself by fleeing. All this was after I’d saved him. I was sure that’s what he’d done, used the same trick I had used. It had saved us both.

Though he has a slight Asian accent, his words are perfectly clear; he sounds very much like an American kid. He is still looking through the mostly shut door so I can’t see him properly.

“Why can’t you let us in?” I ask.

“It’s complicated,” he says.

I pause to think, and Joy beats me to the punch. “You can come to our house,” she says. “No one’s home but us. Our parents are both staying in town tonight. We have the house to ourselves. We can talk there. We don’t have to come in.”

He’s silent again for several moments, and so she prompts him. “You were staring at both of us when we were naked. You’ve done it before. Don’t you think you owe us an explanation—or an apology or something?” Then I’m surprised, not because she didn’t sound mad, but because she smiles at him. She has an awfully pretty smile, and he’s our age. How can he help but be seduced by that smile?

He hesitates, then says, “OK. But you can’t come in. Go back to the sidewalk. I’ll meet you there.”

Joy and I back off from the door, go down the two front steps and walk back to the sidewalk. I guess he’s afraid if he opens the door and we’re right there, we might barge in. When we’re on the sidewalk, he closes the door and I can faintly hear the safety chain being slid off its plate. He opens the door, steps out, pulls the door fast, checks to see that it’s locked and comes to where we’re standing.

“I’m Jody,” I say. “This is Joy.”

“I was wondering what your names were,” he says. “You’re twins.”

“Duh,” Joy says. I laugh, and he does, too.

“I’m Li Cheng,” he says. “Spelled L - I, but pronounced Lee.”

“Are you Chinese or Japanese or something else?” I ask. That’s not rude, is it? I don’t think it is.

Joy responds before he can answer. “Let’s walk. We can talk while doing that. Otherwise, we’ll be standing here all night.”

So we walked. Walking beside Li, I didn’t have much chance to really look at him. It was dark, and I only had him in profile. He was just my size. I found out that he was thirteen like me and that he’d been living in the house behind us for a couple of weeks, ever since his school in China had been dismissed for the summer.

“Do the owners know? Did you break in? Are you all alone? Did you run away? Do your parents know where you are? How are you getting food to eat?” I had a hundred more questions, and they mostly had something to do with the fact he’d been here a few weeks, yet I’d never seen him till this afternoon, and the house had always appeared empty; he was thirteen yet seemed to be living on his own.

He giggled. I guess he thought the way I ran those questions at him all at once was funny. “I’m alone. I’ll tell you about it when we get to your house. I can’t see your faces out here, walking like this, and I want to be able to see how you react to what I tell you.”

“How come you speak English so well if you’ve just come from China?” I asked. Maybe he’d answer that while we walked. And it was only one question.

“Partly because they teach it in the school in China but mostly because I lived here in the U.S. before. I lived here for four years—from ages five through nine—and I learned English then.”

“You speak it very well,” Joy said. I told her in my head not to be a kiss-ass. She snorted in her head.

We finally got back to our house. We went in and sat in the kitchen, and he was finally able to see me as well as I could see him. He was cute! I don’t know why that surprised me so much, but maybe it was because I’d never met any Chinese boys before who were nearly as cute as Li was. Seeing him up close and personal, I was having a hard time not staring at him.

I hadn’t really seen him except from a good distance when he was with Ken. Now I could study him. His hair was long, and to me it seemed to be cut more in an American style than a less-chic Chinese one. While admiring him, I asked him why he was here and why alone.

“It’s what my parents decided for me. It’s hard to get into a good college in China. There are too many people and not enough good colleges. The government has some say in who goes, too. There’s a very hard test you have to take called the gaokao to qualify. Thousands of kids don’t get accepted. In the U.S., anyone who’s qualified and can afford it can go. But it’s better if you’ve gone to school here, speak the language like an American, know the culture, all that stuff. It not only helps in your admission selection but with the coursework, too. Lots of kids from China and Japan come here for high school just for this reason. My parents sent me here.”

“But all alone? You’re the same age I am.”

“And you’re almost alone, too. I’ve spent a lot of time watching you. You’re alone a lot. You get by OK.”

I wanted to talk about him, not us. “How do you eat? Do you cook?”

“Yeah, but mostly rice,” he said, and grinned. Oh, my God. That was the first time I saw him grin or smile. It transformed him from a sober, formal, mature-looking person into a kid. A happy-looking kid with sparkling eyes and a sense of humor. Wow! He went on, saying, “I eat mostly rice because it’s cheap and anyone with half a brain can cook it. So that’s my diet. With the occasional hotdog and salad, too.”

“You can’t,” I said. “You’d have to go shopping to get that stuff, and I’d have seen you. Yesterday was the only day I ever saw you. How come you never go outside?”

He grinned again. He had to stop doing that. It was affecting me in ways I didn’t want to be affected. Joy looked at me, raised both eyebrows and grinned. Damn!

“You think I’m lying to you?” He asked it in a funny way, not a belligerent or aggressive one. I had to grin, too.

“No. Well, maybe. I’d have seen you riding your bike if you have one.”

“Well, I don’t. Going outside is . . . well, I have to be careful. But food—there’re ways to get food. All I do is call the store and have it delivered.”

Joy said, “Duh,” for the second time and pointed at me and laughed. I hate it when she does that. But I knew why she did; we got all our pre-cooked meals the same way—by delivery. Then she said, “You’re skinny. You need better food than just rice and hotdogs. I’m going to fix you a meal.”

I thought he’d argue. Most kids would argue out of pride, would insist they were fine. He didn’t. He smiled at her and said that was awfully kind of her and that he was almost always hungry. I understood that; I was like that, too. She heated up one of our frozen meals; he ate it, every scrap of it, making moaning sounds now and then. I guess he liked it. While eating, we learned more about him.

The house he was living in belonged to his parents. His mother’s father had been here and bought it a few years back. He’d passed it on to Li’s parents. Back then, before the population boom, houses had been cheaper in LA and especially in the outer suburbs. His parents had known long before it happened that they’d be sending Li over here when he was thirteen and able to take care of himself. He said, however, that they’d told him he had to be careful. He couldn’t go outside; he couldn’t let people know he was here.

“Why not?” I asked

“Because kids my age aren’t supposed to be living alone. If the authorities find out, I’d probably be put in a foster home. Then I’d have no control over my life, and my parents would get in trouble for abandoning me. So, I’ve been kind of hiding in that house.”

“But what about school, then? How can you enroll without a parent being involved?” Joy asked him.

“When I flew here at the beginning of the summer, my mom came with me. She enrolled me while she was here and made sure I had what was needed at the house. But even there, I’m not supposed to leave any—what’s the word you have for it? Oh, yeah—footprint at all. It’s supposed to look empty. No one will be suspicious that way. They told me to only use my room downstairs, the bathroom and the kitchen. I’m not supposed to go upstairs at all. I’m not supposed to go into the back bedroom up there, or look out the windows from there.”

He grinned then and said the last part looking at me rather than Joy.

“So, you admit you were looking at us. Even in the day when you could see . . . ” I stopped and blushed.

He still was grinning, and he nodded. “I need to tell you something else. Another reason I’m here. I don’t know how true it is, but my parents think that college-admission people in China often discriminate against gay kids. They think I might be gay. Father isn’t OK with that; my mom is a little bit iffy about it but would rather I not be. See, in China, sons are supposed to carry on a family’s good name and reputation and are supposed to marry and have sons of their own. If I’m gay, they know neither of these will happen. In many parts of China, homosexuality isn’t approved of.

“They’re not sure of me but have seen me watching boys. Dad says if I am gay now, I’ll grow out of it. In fact, he insists I do that! However, in any case, they want me to go to college. They’re starting a business and want me to take it over when I’m ready. That means I’ll go to work with them when I have a college degree.”

Wow! I was staring at him without blinking, and he was staring back now. As I watched, the grin faded. I didn’t know what to say, so didn’t say anything and eventually looked away.

Joy wasn’t so squeamish. And she even had some humor in her voice when she spoke. “So that’s why you were looking. You are gay?”

He moved his eyes from mine to hers and had the same laughing tone of voice she had when he answered. “I’m thirteen. Like you guys. And I’m gay. I think about sex a lot. Don’t you guys?”

She nodded and pointed to me. “Especially him.”

I blushed. I won’t say what I communicated to her silently.

Li talked some more about his parents and the business they were starting in China. They both had to be there to get it off the ground; otherwise, his mother would have stayed here with him. They were working long hours and didn’t have much money. They now saw the house as an investment—both an investment and a place for Li to live in the U.S. while finishing his education.

I was still thinking about what we’d just learned. Joy took over the questioner role I’d been filling. Her questions were different from mine. “Aren’t you awfully lonely?” she asked him.

He finished the last bit of his meal, drank some milk, and said, “I am. I spend a lot of time watching you guys when you’re out back. That helps. I feel like I know you and fantasize that we’re friends.”

“We’d like to be,” I said, coming out of my reverie. “And you did save me from Ken.”

“You were trying to save me first,” he countered. “I really liked that.”

Joy looked at the clock. “It’s time for bed. You can sleep here tonight. No reason to walk all the way back. We’ve got lots of rooms, and you can wear some of Jody’s clothes tomorrow. OK?”

He nodded. It looked like he was happy to be asked. He probably really was lonely, and that might have been why he accepted the invitation to sleep at our house so readily. Maybe that was even more important than not having to trudge all the way back home. I felt a rush and had to hold onto myself. He was going to sleep here! We’d never had anyone sleep over before. And certainly not a boy. Not one with a devilish grin that gave me strange feelings.

We both got him settled in one of our spare bedrooms, just down the hall from me. I asked if he wanted pajamas, and he said he didn’t use them. He didn’t even blush like I would have if I’d been asked that. He was certainly more self-assured than I thought I’d ever be. I wondered if living alone for a few weeks had been part of that or if he’d always been this way.

I slept well that night. No nightmares at all. And when I got up in the morning, Dad and Mom were there. They’d come home late the night before.

Mom had actually tried to fix breakfast. She’d way overcooked the scrambled eggs; they were brown on the bottom and tasted nasty. The bacon still had some flabby fatty places; I like mine crisp. I looked at what she was putting on the table, got up and made myself a bowl of cereal. OK, OK, don’t get on my case. I know, she did try. Too little, too late, and badly done; that’s not how to make my heart respond with warm feelings in the morning.

Joy and Li weren’t down yet. That was good. I could broach the subject of Li without him listening.

Dad was reading his paper. He hardly looked up. Mom was pouring them both coffee that smelled a little burned to me. I spoke to her. “We have a guest. A boy slept over last night. He and Joy will be down in a minute or so, I’d guess. I haven’t seen them yet today.”

OK, after saying that, I realized I could have worded it a little better, been a little less ambiguous over last night’s sleeping arrangements. I could hear what I’d sounded like, and so could Dad. It got him to lower the paper enough to see over the top.

It was Mom who spoke, however. “Sleepover? A boy? With Joy?” Those last two words were spoken in a louder, higher-pitched voice.

I broke in before she could go any further. “Not with Joy. He slept in the spare room. I guess. Well, no, I shouldn’t say ‘guess’. We put him in the spare room. I’m sure he slept there. I didn’t hear anyone sneaking around, and I slept really well. Uh, I mean, I usually sleep pretty lightly, and last night nothing disturbed me. Like it would have had someone been changing bedrooms. Or groaning.”

I probably shouldn’t have added that last bit, which was meant to be funny but brought a look of horror to Mom’s eyes. I could tell by both their expressions I wasn’t doing a very good job of alleviating any worries I’d caused them. I was about to tell them that Li was gay so there was no problem but then realized that might not help at all, especially if I wanted him to sleep here again, which I did. Or would they worry just as much if it were I they’d be worrying about rather than Joy? I had no idea.

Dad wasn’t having it as it stood, however. “Jody, you know what we think about you guys having people over when we’re not here. We’ve talked about this.”

At some point in a teen’s life, he has to argue with his parents. I never had, not once. Perhaps my response right then to what he had said had more impact because of that. What I said was, “Yeah, I know it was talked about. You talked, we didn’t say anything. And while your edict sounded reasonable from a couple of viewpoints, if you then look at what you meant by the phrase ‘when we’re not here’, and what that actually means is, we could rarely ever have any friends over because you’re rarely here, which would greatly diminish our ability to cultivate friends. Neither of you is too old that you don’t remember how important it is for teens, especially young teens, to have friends. Without them you’re isolated, often picked on, have low self-esteem, and often never learn any social skills. So, we decided if you’re not doing your part by being here to see to our well-being, we’ll have to take up some of the slack that causes and make some decisions on our own.”

Wow! Had I really said that? They both were looking at me like I’d suddenly grown antlers or my skin was on inside out. I got that. I rarely said more than three words in a row to them. I myself was a little surprised I got it all out.

As they seemed momentarily tongue-tied, I continued. “Li should be down any time now. Be nice. He’s my age and his parents are away on a business trip. I guess you understand how business interferes now and then with your home life. Li’ll probably be here for a couple of days. We’ll feed him, too. He’s too thin; he hasn’t been getting enough food. Just be pleasant to him. We’ve got this under control.”

Dad rolled his eyes, maybe just because he couldn’t believe this was me saying this, and he looked at Mom who was still staring at me. I added milk to my cereal and took a spoonful, acting like nothing out of the ordinary had happened.

“Jody?” my Mom finally said, sounding tentative. She never was tentative! She was a lawyer and used to engaging in verbal battles; a strong front and adversarial manner of speaking was her wont.

“Oh, another thing, Mom. Do you know how to file for a restraining order? There’s this kid . . . ”

“There’s no need for that.”

I looked up. Li had joined us. And he was speaking to my mom.

I have to say, he impressed me to the extent I was suddenly a bit nervous about him. I hadn’t been before; it had been as though we were equals when we met. I’d even bossed him around a bit. But now? He walked into that kitchen like he belonged there and spoke to my parents like he’d known them for years; he spoke like they all got along like gangbusters. Me? On meeting adults for the first time, I do a sweet imitation of a clam, my lips tending to stay as firmly closed as its shell. Nodding or shaking my head was about the best I could do. Here, he was speaking up, and not only that, telling my mother she could disregard what I’d just asked her about.

“I’ll talk to the kid Jody’s referring to,” he finished. “That’ll be the end of it. Jody will come with me. We’ll take care of it today.”

My mom looked nonplused. I hurried to say, “Mom, Dad, this is Li. We just met yesterday, but Joy and I like him and he’s going to stay with us a couple of days till his parents return from their business trip.” I looked at Li when saying the end of that. He needed to be clued in on the lie I’d already told the ’rents.

“Well,” my mom started but was interrupted when my dad stood up. I could read his face; he wasn’t happy. Li stepped over to him, however, and extended his hand. “Hi, Mister Jody’s dad! Sorry, I don’t know his or your last name. I’m Li. Li Cheng.” And he smiled. I didn’t think anyone could resist that smile, but it didn’t seem to affect Dad at all. Go figure. Dad was projecting the magisterial presence he often adopted with strangers. He didn’t get the chance to speak, however.

Joy chose that time to come in, and she preempted anything he was about to say. “Oh, you’ve both met Li,” she said, and I rushed into the breach that was about to appear, breaking in to say, “Yeah, and I told them how he’d be here for a few days till his parents finish up their business deal.”

Our two ’rents looked at each other, and then Mom said, “Well, we need to talk about this.”

I didn’t have any idea where my sudden personality change—my new chutzpah, in fact—came from, but I spoke up again. Yeah, me! I didn’t expect it, either.

“Uh, Mom, we already invited him to stay, and he reluctantly accepted because he knew it was best for him. We’re helping him out. That’s the way it’s going to be.” I finished and looked her in the eye, a challenging look, and just as incredible coming from me as the words I was saying. It certainly caught her off guard.

Then Joy sealed the deal. She was good at that, and it wasn’t unexpected, coming from her. “He’ll be in good hands. We’ll look after him, and he’ll be safe here. This way you won’t have to do all that work on a restraining order. I’m sure you have better things to do with your time.” She smiled at Mom.

Mom was being hit from both sides, and with conflicting plans for the problem either she or Li was going to solve and that she knew nothing about. I’d thought it unlikely Mom would look to Dad for help because that wasn’t what she was like. She didn’t think she ever needed help from anyone. That was why I’d chosen her to challenge about Li staying with us.

She had to make a decision or defer to Dad, and she wasn’t about to do that. That’s where Joy’s smile was so instrumental. That smile allowed her not to go on the defensive, and so she made a decision that was in line with what we wanted rather than having to defend her own position. Joy was subtle like that.

“OK,” Mom said and actually smiled at Li. Dad threw his paper on the table and walked out. I repressed a grin. Looking triumphant would have been exactly the wrong way to play it.

Mom had to have the last word, though. “What’s all this about a restraining order?” she asked, looking at me.

I shook my head, thinking it would help cover the lie I was about to tell. “That was for Li, not me. But it sounds like he doesn’t want it now. It’s his business, not mine.”

She stared at me for a moment, then switched her gaze to Li. He just smiled at her and looked down, trying to appear embarrassed.

She said, “Hrmph,” and that was the last that was said about it.

Mom and Dad had left, neither even having bothered to say goodbye, probably because their heads were already back in their offices. But I think Dad was pissed that we’d called the shots for once, and Mom was still wondering about my sudden transformation from a sad weed to someone who was standing up for himself. Mom did leave a note saying they’d both be entertaining clients that night and so both were staying in town. Even though Li was right there, I asked Joy, out loud, what had come over me. She often understood me better than I did.

She smiled. “I think you finally had something you felt strongly about, something to actually fight for for once.”

“Huh? What?”

She just laughed and walked off, saying she was going over to Jill’s house. Jill was her best friend. She said she wasn’t sure when she’d be back, but to have fun.

Then we were alone and Li was grinning at me, making my stomach feel like ants were building a nest in it. Too much had happened too quickly, and now I wasn’t sure what I felt but did know I was restless as hell. I said, “Let’s go swimming.”

He shook his head. “I don’t know how. And besides, I told your mom we needed to deal with Ken. Let’s do that.”

“We can’t! He’d kill us both.”

“Maybe not. Anyway, we can’t go the rest of the summer being afraid of him. That’s no way to live. So he’s bigger than we are. So what? We’ve got better minds than he has. I know that from talking to him for two minutes. Mind over matter; isn’t that one of your cockeyed expressions?” He snickered. I was going to say something just as confrontational about the Chinese, but I couldn’t think of anything. He knew much more about my country than I did about his.

Then something occurred to me: he’d come here rather than stay there, so obviously this country had more to offer him than his own did. His parents certainly thought so at least. But as I rehearsed a way to say something rude, I realized how mean it might sound, and how much it might make him defensive, and I didn’t want to do either. So, instead, I asked, “What do you want to do about Ken? Something that won’t get us killed, I hope.”

“Invite him over. Tell him we need to talk.”

“You think he’ll come?”

“I’m sure he will. Let’s go knock on his door.”

I was delighted, really delighted, thinking about doing that! Sure I was! Not! And why did we want Ken here? But Li was already headed for the door, and I wasn’t going to let him go alone.

We walk down to Ken’s house, and with no hesitation at all, Li goes up to the front door and rings the bell.

Missy answers, and Li asks to speak to Ken. When Ken appears, looking as muscular as yesterday, Li doesn’t beat around the bush. “Come over to Jody’s house. We need to explain the facts of life to you. When you’re feeling brave enough to face us, we’ll be waiting in the front yard.” Then he turns and walks away. You’d better believe I don’t wait to discuss the time of day with Ken. I am right on Li’s shoulder. It’s hard, but he doesn’t look back, so I don’t, either. When we are out of earshot of Ken, I ask, “Are you crazy?”

“Not a bit,” Li says with a giggle. “What? You thought I was going to politely ask him over to drink tea with us? No, I wanted him to come. Challenging him like that will bring him. Don’t you think?”

I don’t bother to answer. We are in my front yard by now, and I turn and see Ken coming. Li’s question has become moot.

Ken walks up to meet Li, who has stepped in front of me. I’m not complaining about that at all. Maybe Ken will wear himself out beating Li down—or at least bust up his knuckles a bit—and he won’t be able to hit me quite as hard if I go second.

Li steps forward to meet him. Ken doesn’t look like he’s about to stop, so Li puts out his hand like a traffic cop and says in a harder voice than I’ve heard him use before, “Stop right there!”

Ken says, “Huh?” but stops.

“You have to know what’s happening here before I kick your ass. Jody and I are untouchable this summer. You’re to stay away from us entirely. You see us, you pay us no attention at all. That’s what you’re going to do or you’re going to spend some time in the hospital, and that’s not a fun place to spend your summer, especially dealing with the pain. Now, I’ve explained this so you know what to do after this is over. So, that was the talking part. Now for the doing part, the part where I show you why you’re going to do what I just told you. I’m going to hurt you now but not very much. The very much comes if you ignore what I just told you. OK, enough of that. Now the ass-kicking. Let’s get it on.”

I think if I’d been an innocent bystander, I’d have laughed. Here’s this small, insipid-appearing Chinese boy talking trash to this solidly built American boy who probably outweighs him by 30 or 40 pounds and is at least four inches taller. Li beckons Ken to come get him with a wave of his hand. Standing relaxed, looking more like a target for Ken to do what he will to rather than any kind of worthy threat or opponent, it seems to me that Li is about to get killed. I take a couple of steps backwards, taking out my phone as I do. I dial 9 and 1 and leave my finger on the 1 button, ready to press it in a hurry when I need to. I don’t know if I’ll need the cops or the EMTs. Probably both. I’ll press the button when Ken strikes his first blow.

Ken smiles. Then he rushes forward, probably having decided a bull rush is his best move. How could Li possibly stand up to such a tactic when he’s outweighed by so much?

Ken rushes at Li, and when he gets there I can’t quite see what happens because it’s way too fast, but I catch a glimpse of Li sidestepping Ken’s rush and grabbing Ken’s shirt, of Li turning a bit sideways, of Li twisting away still holding the shirt, and then, suddenly, Ken flipping, soaring through the air and crashing onto his back on the lawn. Li stands over him, looking down. I move my finger away from the 1 button.

“Get up,” Li says. “You’re just winded. I’ll give you time to get your breath back before we go again. Fair’s fair.”

We have to wait a bit, but Ken does get up. Then he just stands still, looking at Li, confusion apparent.

“You chickening out already?” Li asks. “That wasn’t much of an ass-kicking if you ask me. Pretty weak. I barely hurt you at all. No surprise you’d want to stop, though. I figured you were more talk than action. Most of you over-muscled, small-brained bullies are.”

Ken stares at Li a little longer. I can see what he’s seeing: just how small Li is. He can also hear the derision in Li’s voice. It’s too much for Ken; he goes after Li again. This time he’s more cautious, though. No rushing, no charging and he puts his fists up as he moves toward Li cautiously.

When Ken’s within striking distance, he fakes a left-hand punch, then leans forward and throws a hard right at Li.

Somehow, it looks to me like Li pulls his head back a half-inch at the last moment and the punch sails by; like lightning, Li catches Ken’s wrist as it’s flying past and does something I can’t quite make out, but Ken shrieks in pain, really shrieks, and before I can believe it, he’s on his back again. This time, Li follows him to the ground, lands with both knees on Ken’s chest with a thump and flattens his right hand into a karate-chop shape, raises it high and strikes hard down toward Ken’s exposed throat.

I can see Ken’s eyes widen as the hand is coming down. Li stops the blow just as it touches Ken’s Adam’s apple. He stares into Ken’s eyes and says, “You’ve been warned. That pain you feel now in your wrist and shoulder would be much, much worse if I’d held on a half-second longer after I grabbed your arm. I’d have dislocated your shoulder. My karate chop, had I finished it, would have broken your voice box; had I, you’d be really lucky if you could ever speak again. You can ignore my warning, but I don’t believe in second chances. Now, beat it.”

Li gets off him, turns his back, and walks over to me. He winks at me. We both stand there as Ken gets up, favoring his right arm. He doesn’t look at us; he just leaves.

“What was that?” I ask. I don’t know whether to admire Li or be afraid of him.

Li isn’t even breathing hard. “It’s a combination of things. A little jiujitsu, a bit of aikido, and an almost chop of karate. I don’t think we have to worry about him. Now, you said something about swimming. Can you teach me?”

He was entirely unaffected by what had just happened. I was breathing like a racehorse after the Kentucky Derby, and I hadn’t even been involved. Fighting always affected me that way.

He was still waiting for me to answer, so I did. “Yeah, I can teach you. Swimming’s easy. And you can teach me how to do what you just did.”

He smiled. “That takes quite a few years to learn. My parents knew they’d be sending me here alone and so enrolled me in classes so I could learn how to protect myself. But I can teach you some easy stuff, and that’ll probably be enough. You saw how quickly I took the fight out of a kid who thought he loved to fight. He didn’t. He loved to intimidate kids and be a menace. It made him feel powerful. But he knew deep inside he wasn’t. And when he faced someone who wasn’t afraid of him, someone who knew how to handle himself, he saw the error of his ways. He learned that actually fighting someone who isn’t scared is something he wasn’t good at.”

We were in the pool. He was distinctly and unabashedly afraid of the water. I was amazed. He wasn’t a bit scared when a gorilla-sized bully was attacking him, but just trying to get him to hold his breath and lower his face into the water frightened him to death.

I wasn’t giving up, though. What I was doing . . . well, I was loving this, this teaching-him-how-to-swim business. I’d told him what the pool rules were: no bathing suits. He believed me because he’d watched Joy and me swim, and we never wore them when the ’rents were absent, which was most of the time.

I undressed for the lesson in the pool as though it was the easiest thing in the world, all the time afraid I’d bone up. Why I didn’t, I have no idea. Nerves, probably. He did throw a bone, maybe because he was gay or wasn’t nervous, and he blushed doing it. He was absolutely adorable.

I told him not to be embarrassed, that I got that way all the time, and if we talked about it any longer or if he kept staring at my lower half, there was no doubt that I’d do the same sooner rather than later. So, the rat, he kept talking about it and made his staring more obvious, probably to check if I was a liar or not. I wasn’t, but he didn’t get to see for sure because I ran for the pool, staying ahead of him and jumping in. He couldn’t do that himself because of his aforementioned fear. So, he stood on the edge, swearing at me, and I got a terrific view of him. Didn’t help my condition any, but at least what he was trying to see was underwater, and all I had to do was keep moving a little bit so the water would make anything he could see slightly blurry.

Finally, I got him to walk down the steps. It was only four-feet deep in the shallow end, so he had plenty of air between his nose and the water; no reason to be worried at all. I was five-feet tall, and so was he. Neither of us would make a scale reach triple digits.

I had him walk around in the shallow end, getting used to being partly submerged, to the resistance of the water against his movements, to the way the water bounced off the walls and so splashed against him from several directions at once. He took my hand while doing this. I didn’t object.

But he did not want to put his face in the water. I tried any number of enticements, but he just wouldn’t do it. So I tried the ultimate.

“OK, I’ll tell you what. Upstairs, you wanted to see me hard. You didn’t. And you can’t see much now because we keep moving and that moves the water and distorts whatever is underneath. But, if you put your face in the water and open your eyes, you can see pretty much everything that’s under there fairly clearly. So, here’s the deal. I’m still hard. Can’t help it. Somehow, you holding my hand and your bare hip rubbing against mine every other step you take keeps me this way. And if you want to see what you want to see, I’ll stand still. All you have to do is take a breath, hold it, and put your face in the water, and there I’ll be. Now, I have to tell you this to be fair: putting your face in the water disturbs it. So, you have to hold your face still under the water for a few seconds till the water settles for a really clear view.”

He looked at me, and I looked back. Then he grinned. If I hadn’t been hard, that alone would have done the trick. Damn, he was cute! Totally. Then he took a deep breath and without hesitation, shoved his face into the water. Not only that, he shoved his whole head in so as to get as near as possible to the object of his attention.

It was a little embarrassing, but sexy as hell, too. There was no chance I’d soften up anytime soon. None at all.

I had no need for embarrassment, though. I knew something he might not have. Things underwater get magnified somewhat. No, nothing to be embarrassed about at all.