A tale from a strange and far off place, which has oftimes been mistook for some hidden dale in the high Pennines of Yorkshire.

Happen, at thirteen wee Georgie were physically well on his way to manhood. Indeed them as had seen Georgie and t’other boys from village skinny dipping in t'lake behind the Big House could have telled thee, there were nowt wee about him no more. Emotionally things was different. Although he were no cry baby, he would still run for his ma if he were upset by summat and gabble at her nineteen to dozen until she calmed him enough to slow down so as she could understand what were wrong.

The mean minded old biddies of the village would whisper in their gossip that Georgie were nobbut nineteen and six in pound and would ne’er grow up nor amount to much. Them as knew Georgie, knew better. He might appear dim but somehow Georgie allus got what Georgie wanted no matter who he asked it off. Mebee a better life skill than any bookish learning.

Not that he were spoiled: his parents had no brass to spoil him wi’ even if they wanted. Now, like all o’t’village, they were of opinion that a boy should have a pet: to learn what keeping a pet learns a boy. So some years ago Georgie, whose nature was to be different, set his heart on having a pet rabbit. Not a proper pet for boy thought his father, which should be a dog if you could afford it, which they couldn’t, or a ferret which they could and ferrets could be used for catching rabbits.

Georgie got a rabbit kitten which cost his father nowt ‘cos it were a feral orphan, it’s mother having found her way into the family’s cooking pot, and if Georgie lost interest in keeping the kit, it too could find its way to table.

But Georgie didn’t lose interest in his pet. He diligently saw to its needs: feeding it and regularly changing the bedding in its hutch, which his father had made for him as his ma weren’t having no rabbit running round in t’house. Georgie worked his magic on the animal and soon had it tame enough to handle and groom, summat not easily done with a feral kit. It had cost Georgie a few painful nips, but no more than he would have had from a ferret.

His father was sufficiently impressed with Georgie’s efforts that when he suggested his pet needed another rabbit to keep it company, he was happy to find another orphan kit for Georgie.

Of course with two rabbits, it weren’t long before Georgie caught ’em doing what rabbits do and his father had to explain that one mun be male and one mun be female. The now tame rabbits were upended so as Georgie could see the difference in their anatomy. Living in a rural community Georgie already had some idea from watching the beasts and pigs and sheep in the fields around the village.

Georgie also knew some of these animals were sold for slaughter to bring money into the village and put food on peoples’ plates. So when t’ litter arrived a few weeks later, he weren’t surprised to get a talk from his father on animal husbandry and how rabbits was bred for market before townsfolk had gotten squeamish about eatting ’em.

“The breeders would geld t’ bucks,” his father had said. “It helped ’em put on mooar weight, and also made ’em less aggressive. Some used to call the geldings ‘lapins’, from the French. If tha’ doesn’t want to breed from ’em, tha’ should geld t’ bucks when big enough. Ah can tell thee how to do’un.”

Since the doe were soon pregnant again, Georgie reckoned it were also a good idea to geld all bar one of t’ bucks to stop being o’er run wi’ rabbits. To keep bucks apart from does, Georgie helped his father build a second hutch for t’ bucks. To help keep numbers down, oftimes Georgie’s father would say that a fox had gotten into one o’ the hutches and killed a rabbit, usually a doe, and the family would have rabbit pie for supper those nights. Georgie were getting suspicious that the fox were actually his dad which it were — when he happened to see a fox lookin’ in t’doe hutch and one of rabbits drop dead from fright.

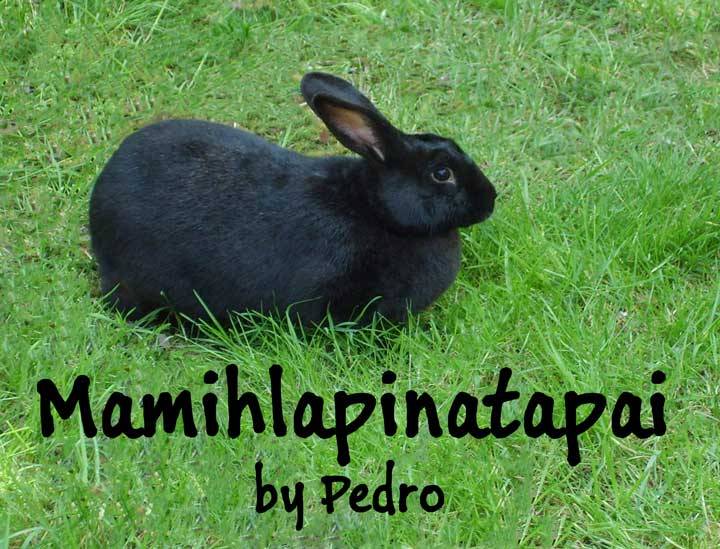

By a quirk of genetics, one of the litters produced a buck rabbit that were all black instead of usual grey wi’ brown ticking. Georgie wanted to know how that happened. It got him another talk from his father, this time about blood lines and why it weren’t a good idea to mate it with any of Georgie’s does which were all its sisters and half-sisters. It were agreed it would be gelded along with t’other bucks.

His black buck growed into a fine specimen and Georgie spent extra care on him and trained him to be used to being out of the hutch and to follow him around. In fact Georgie lost interest in his other rabbits. Not to the point of neglect mind, but to where he no longer wanted to breed from ’em and was no longer upset by the predations of the fox or his father. So by the time Georgie was thirteen he were down to t’ black buck and a couple of does.

Every year the village held a fete on t’green. There were no fixed date: it were allus held on first dry day in August which meant it were oftimes held toward end of September. In spite of its impromptu nature, it were a grand affair, well a grand affair for t’village, with competitions for best home-made cakes and jams or home grown vegetables. There were livestock classes for local farmers and small holders and a pet show for under-fifteens. All-comers would bring a picnic and spread themselves around spare areas of the green, enjoying the day. Sir Henry from the Big House would lay on a barrel of beer for all his tenants and workers.

Georgie decided to enter the black buck in the pet show. It were now about fourteen month old. He groomed it to look its best. His father told him not to be disappointed if he didn’t win. Sir Henry would be judging and Sir Henry were a dog man. A dog, usually a gun dog, had won every year since Sir Henry had taken over judging from his late father.

The surprise was that Sir Henry did not do the judging. He thought somebody nearer the contestants’ age should judge and handed over the job to his son Thomas. Thomas were also thirteen, but not quite as far through puberty as Georgie. He were however emotionally more mature and self-assured. Serving time at a second tier boarding school had given him that confidence.

Georgie had seen Thomas in the village when he were not away at school, but although he thought he would like to know more about the boy it was not his place to start a conversation with someone from the Big House. Similarly Thomas had seen Georgie around but had lacked some excuse for talking to him. They had shared looks before as though wanting to start something, but now Thomas had a chance to talk, a very good chance.

Thomas took his judging seriously, and asked meaningful questions of each contestant and inspecting the pets carefully. He spent the longest time talking with Georgie about his rabbit, inspecting not just the animal but Georgie as well. So long that Sir Henry, who was there just in case, had to cough discreetly to get Thomas to move on to the next pet.

The buck won Georgie a commendation for best rabbit, but didn’t win the overall prize. That went, not to a dog, but to a nicely turned out and obviously well-kept ferret with unusual markings. Sir Henry was heard to mutter something about ‘choosing a bloody ferret over all those lovely dogs.’

Georgie and his rabbit were headin’ for where his parents were sat, when he was intercepted by Thomas.

“I’m sorry I couldn’t give the prize to your beautiful sable buck,” he said to Georgie. “I would have been accused of favouritism. I used to keep rabbits myself before I was sent away to school.”

“That’s alreet,” replied an uncharacteristically bashful Georgie. “It were a grand ferret what you chose.”

Thomas suggested they sit down and they fell into talking abaht rabbits, but it were one of those talkings punctuated by long pauses where each were thinking t’same and it weren’t abaht rabbits.

They were disturbed by a loud shout from the man of the family picnicking next to where they was sat.

“Get away from them pies you thieving black boogger.”

The boys looked round to see the sable with the remains of a small pie in its forepaws being brushed away from a plate of pies by back o’ the man’s hand.

Georgie was starting to apologise to t’man and gather up his rabbit when it dropped dead from shock of being shouted at an’ cuffed. Upset, Georgie upped and ran for his ma.

“Mamihlapinatapai,” he wailed to her as she took him into a comforting hug. “Anaman cuffeditanits deyd!”

His ma calmed him enough to get him to repeat what he’d said only slower.

“Oh Ma,” he said, “mi lapin ett some man’s pie, so ’ee cuffed it awa’ an’ now its deyd.”

By now Thomas had mollified t’man as had shouted at the rabbit o’er his lost pie — cheese an’ spinach it were — picked up the corpse and found Georgie and his ma in t’ throng.

Thomas was able to reassure Georgie that the man had meant his rabbit no harm, an’ these things happen to rabbits if they gets o’er stressed an’ the fete would have been stressful.

For them as were watching they would have seen that by time Thomas had finished talking he were holding Georgie by the hand and were leading him off to bury the corpse in t’garden behind Georgie’s cottage. Georgie’s father were thinking it were a waste of a good rabbit, but Ma told ’im not to say owt. There were still the two does.

From that day on, whenever Thomas weren’t away at school, he and Georgie would oftimes be together. The biddies would say in their gossip that Georgie were different, and Thomas, being from Big House, were different from ordinary folk by definition. If they were being different together they weren’t disturbing other folk.

Just how different they were was showed up when Thomas reached the age to take a wife to ensure the blood line. He found one with a friend who would make a wife for Georgie who by then had a job in the Big House. More than one maid was telled to keep her trap shut when she questioned why the two husbands shared one bedroom and the two wives another. Both men did their duty by the blood line — heir an’ spare but the biddies had more to talk abaht when Thomas’ second looked like Georgie an’ Georgie’s second took after Thomas.

An’ when Thomas inherited, Georgie became his chief steward. Not bad for a boy who was thought would ne’er amount to much.

.oOo.

The End

If you enjoyed reading this story, please let me know! Authors thrive by the feedback they receive from readers. It’s easy: just click on the email link at the bottom of this page to send me a message. Say “Hi” and tell me what you think about ‘Mamihlapinatapai’ — Thanks.

This story is Copyright © 2018-2024 by Pedro; the image is Copyright © 2018-2024 by Colin Kelly. They cannot be reproduced without express written consent. Codey’s World web site has written permission to publish this story and to use the original image. No other rights are granted. The original image is by Xosema [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)] from Wikimedia Commons.

Disclaimer: All publicly recognizable characters, settings, etc. are the property of their respective owners. The original characters and plot are the property of the author. The author is in no way associated with the owners, creators, or producers of any media franchise. No copyright infringement is intended.

This story may contain occasional references to minors who are or may be gay. If it were a movie, it would be rated PG (in a more enlightened time it would be rated G). If reading this type of material is illegal where you live, or if you are too young to read this type of material based on the laws where you live, or if your parents don’t want you to read this type of material, or if you find this type of material morally or otherwise objectionable, or if you don’t want to be here, close your browser now. The author neither condones nor advocates the violation of any laws. If you want to be here, but aren’t supposed to be here, be careful and don’t get caught!