Part 13 — Rendezvous with a Star

Tuesday, July 11, 1972

“Oh wow, Dr. Ellis. What do we have today?” I asked as I took a seat at the table in his office. It was Tuesday, and I was meeting with my mentor to discuss progress with my research project. My place at the table was set with a dinner plate and silverware. Arrayed in the center was a large platter with a host of different kinds of food.

“There’s a new Mediterranean restaurant in town. I thought we’d give it a try. We have Donner kabobs with beef, lamb and chicken, seasoned rice, dolmas, homemade pita bread, hummus, baba ganoush, tabbouleh, tahini, tzatziki and labneh. If you ask, I might even be able to tell you what some of those things are,” he added with a laugh.

Taking a little bit of everything, I said, “This reminds me of Greek food.”

“My Turkish students would point out that Greek food came from Turkey, and they wouldn’t be wrong. Mediterranean food comes from all over the Middle East and was spread across the Eastern Mediterranean and North Africa by the Ottoman Empire.”

“Everything’s delicious,” I exclaimed.

“I’m glad you like it,” the professor replied. “So, how are things coming with your programming?”

“It’s a slow process,” I admitted. “I wanted to be sure the calculation of π to 100 decimal places was accurate, so I found a book in the library with nothing but the values of π and e, to something like ten thousand decimal places. It took a lot of going back and forth, but I confirmed that my calculation was accurate.”

“You’ll be sure to list that book in references section of your final report,” Dr. Ellis reminded me.

“Of course,” I agreed. “Now for my program to calculate the value of e to 100 decimal places, I had a bit more difficulty with the series failing to converge. I’d made a really stupid mistake that resulted in an overflow error. I got back reams of gibberish that the guy at the service desk said was a core dump. My algorithm ran until it timed out, and then the entire contents of all of the registers were printed out — as if there was any way to figure out what they meant.

“I ended up adding a print instruction within the loop, so I could see what was happening. That’s how I found my mistake.”

“Sometimes the easiest way to track down a problem is to add diagnostic instructions to your program, even though it means running your program an extra time or two to get those diagnostics,” Dr. Ellis explained. “I didn’t even need to tell you that. You figured it out on your own.

“Any luck in generating a trig function table?”

“Yeah, my algorithm seems to work. The values calculated at zero, thirty, 60 and ninety degrees come out as they should, but those have exact solutions. Everything else is off a little bit from the numbers in the reference tables. Perhaps there’s a problem with rounding error or truncation error. Maybe I need to add greater precision.”

“You might want to check out some other reference tables,” my mentor suggested. “Some of the older ones were first published when the only computers were mechanical, like the old adding machines. For practicality’s sake, they calculated only some of the values and used interpolation for the rest, yielding numbers that aren’t as accurate. Even with subsequent editions, those inaccurate numbers are still out there.”

“Wow, I hadn’t even considered the possibility that the reference books are wrong,” I responded. “I’ll look into that.”

“I probably don’t need to tell you that you still have to write seven more programs, including the Fourier algorithm,” Dr. Ellis reminded me.

“Yes, I know that,” I acknowledged. “In some ways it’s getting easier each time, but I’m discovering new issues as the programs become more complex.”

“That’s to be expected,” he agreed, “but you do need to pick up the pace a bit, even if it means taking advantage of that key I gave you. Let’s hold off on that for now, but if you haven’t completed five of the ten programs by Friday, you’ll have to consider it.”

“I realize that,” I answered. “I’m putting in more time after hours now and I may need to come in on the weekends. I can’t come in this weekend, though. My friends and I are going to a double-feature on Saturday, and I’m going on a trip with the group to the Amish country on Sunday.”

“Your education should never come at the expense of having fun,” Dr. Ellis acknowledged. “If we have to, we’ll drop one or two of the problems, but the Fourier problem is essential and cannot be skipped.”

“I won’t let you down,” I replied.

“Even if you can’t finish it, you won’t be letting me down,” Dr. Ellis stated emphatically. “Finishing the Fourier problem is as much for you as it is for me.”

<> <> <>

“What a circus,” Larry exclaimed. “In 1968, they had riots in the streets. But rather than try to restore sanity, they banished the party establishment and invited blacks, women and homos to fill the convention hall.” I noticed that Kyle, his roommate, winced on hearing that.

“Not that I like the idea of quotas, but blacks are a significant part of the Democratic base,” I noted. I almost added that he sounded like a racist but stopped short of that.

Our group of ten was lounging around in Larry and Kyle’s room rather than in Greg and Gary’s. For whatever reason, Larry had brought a TV with him. It was only a sixteen-inch black and white model similar to the Zenith set in my bedroom back home — the TV I inherited when Mom finally decided to buy a color TV for the family room. I’d not brought mine with me because there wasn’t any point. Only reruns were on in the summer.

But Larry brought his and we were watching the Democratic National Convention, such as it was, which had started on Monday. We could’ve watched it in the lounge, on a large 25-inch TV, and in color, no less. But we were a tight-knit group and watching it in private allowed us to speak our minds.

“I get that they’re tryin’ to have the delegates be more representative of the people who elected them,” Larry continued, “but they’re gonna need all the help they can get. The party establishment holds the purse strings, so where are they? It takes money to run a campaign. Hell, they banished all of the big-city mayors except for Lindsey of New York, a former Republican. And where are the labor unions? Those union endorsements would go a long way in helping McGovern to win. Sure, he appeals to the young, but none of us can vote yet.”

“It’s all just political theater anyway,” Greg added.

“So then why are most of the activities happening after their audience has already gone to bed?” Paul asked. “There’s not much point in televising it, once the networks have signed off the air.”

“Well, it’s a lot cooler in Miami Beach at night than during the day,” Brandon quipped. “Believe me, I’m from Nashville and I know about heat, but ours is nothing compared to Miami. Why they’d hold the convention there in the middle of the summer is beyond me.”

“The Republicans are holding their convention in the same convention hall in August,” I pointed out. “Do they actually think they can sway the voters in a Democratic stronghold like Florida by holding their convention there?”

“Nixon will win Florida,” Raj countered. “I guarantee it.”

“With these bozos running the show, you might be right,” Larry agreed.

The TV kind of faded into the background as we continued our conversation.

“So did you get the tickets for the Saturday matinee?” I asked, looking at Garry.

Shaking his head, he replied, “They were sold out. I hope you guys don’t mind, but I got us tickets to the evening double feature. It’s a dollar more at $3.50 a ticket, but at least we won’t hafta deal with a bunch of screaming kiddies.”

“What time does it start?” I asked.

“It starts at 7:00,” he answered.

“Fuck, that means it won’t end ’till around midnight,” Kyle responded. “Some of us have to get up early for the trip to the Amish country.”

“Shit, I forgot about that,” Gary related. “I just didn’t want to take a chance of losing out. How many of you are going on the trip?” I raised my hand, as did Paul, Kyle, Steve, Raj and Brandon.

“Damn, if you guys don’t wanna go, I’ll eat the cost of the tickets,” Gary suggested.

“What’s playing?” I asked.

“The first feature’s Little Big Man and the second is A Man Named Horse,” Gary answered. “They both got tons of critical acclaim.”

“What kind of movies are they? Are they westerns?” I asked. “I’m not a fan of westerns.”

“Yeah, but these aren’t supposed to be shoot-’em-up westerns. They’re revisionist westerns, viewed more through the lens of the Indians than the cowboys. Little Big Man has an all-star cast led by Dustin Hoffman. You remember him, from The Graduate?”

“‘I have one word for you: Plastics’,” Kyle said, quoting the well-known line from the film.

“And wouldn’t we all like to find a Mrs. Robinson?” Larry stated more than asked.

“Great music with one of the best soundtracks of all time. The lyrics from The Sounds of Silence are as profound as anything written by the great philosophers,” Greg added.

Sadly, I’d never seen the movie, ’cause my parents thought I was too young when it came out. I was very familiar with Dustin Hoffman and the music of Simon and Garfunkel, though. Who wasn’t? I answered, “Okay, you can count me in, for the double feature and the trip. I guess I’ll just hafta sleep on the bus.”

“Yeah, same here,” Paul chimed in, and soon everyone agreed.

<> <> <>

Sunday, July 16, 1972

Both movies were fantastic and watching them with friends was the best. I tried to sleep on the bus, but the ride to the Amish country was short. I was tired, but I wasn’t complaining. I’d made decent progress on my research project during the past week but yesterday was a real revelation. Since we didn’t go to the movies until after dinner, I decided to spend some time in the computer lab after the weekly research symposium let out. The turn-around times at the computer service window were less than ten minutes. During the week, it took over an hour to get my printouts back.

Only three of the problems remained, and then I’d need to write up the results and prepare them for presentation in a formal setting. The first problem that remained was writing a program that could print a graph of two arbitrary functions. Although useful by itself, the graphics program could be used to produce plots of all my results. Unfortunately, the IBM 360 installation lacked a graphic plotter. I’d have to use the line printer to make crude approximations. It would be a bit like using a typewriter to produce a facsimile of the Mona Lisa.

Most books, including my Fortran textbook, used what is often called a ‘quick and dirty’ approach, but that resulted in the x and y axes being reversed. I knew how to invert a matrix, so why couldn’t I undo the reversal of the axes in my graphics? However, considering the limited time remaining, perhaps it would be best to stick with a conventional approach. I could always revisit the graphics routine after I finished everything else, if there was still time.

The bus stopped in what, to a city boy like me, looked like the middle of nowhere. As we got off the bus, we could see that we were in a small village, with a few houses, some barns and other farm buildings, and endless fields as far as the eye could see. There were horses grazing nearby and farm implements that looked like they were from a century or two ago.

We were greeted by a group of men with long beards, wearing broad hats and suspenders, and women wearing scarves on their head. Children, who were similarly dressed, scampered about. These people were Amish. We had Amish communities back in Indiana and we sometimes passed through their communities when we went hiking in our state parks.

We were shepherded into some sort of communal hall, where our hosts told us a little about their history and explained the philosophy of the Amish people. Their religion played a role in every aspect of everyday life. The Amish originated in what is now Switzerland, at the time of the Protestant reformation. They diverged from both the Catholics and the Protestants in several key ways and were never more than tenant farmers in their native lands. They split into two, often contentious groups, the Amish and the Mennonites. Starting in the 17th century, they immigrated to America for the promise of land ownership and religious freedom, and spread out from their original settlements in Pennsylvania to much of the U.S.

After a demonstration of Amish methods of farming, we were shepherded back onto our buses and drove for a bit, getting out in what appeared to be another Amish village, but this one had a series of large buildings. More modern farm implements were in evidence, including tractors and pickup trucks. We were shepherded into one of the large buildings and my jaw just about dropped. It was a factory building. All of the equipment was idle but there were lathes, drill presses, band saws, and just about every kind of modern woodworking machinery I could imagine. The wood shop in my high school was pathetic by comparison.

As we explored the factory, a guide explained how the building of furniture had become a major source of income for the Amish. Originally, everything they made was built by hand, but in more recent years they’d come to accept that modern implements only amplified what they could do with their hands, rather than replacing them. Over time, the Amish adapted modern furniture making techniques but with an eye to detail that made Amish furniture a prized addition to any household. Amish furniture was so well made that people were willing to wait months for fabrication of a custom piece and pay a premium price for it.

Although the Amish made the concession of using power tools, the one concession they wouldn’t make was to utilize power from outside their community. They weren’t connected to the power grid. Their philosophy of self-reliance dictated that they had to generate their own power, which meant using diesel generators. Although burning diesel oil is much less polluting than coal, I couldn’t help but wonder about the effects of diesel fumes on their health.

One of the girls in our group asked why the factory wasn’t in operation. An Amish woman answered, “Dear, it’s Sunday. This is the Lord’s day. We don’t work on Sunday. We go to church.”

Once we were back on the buses, we drove for a bit more until we came to the town of Amana, which was much more substantial than the villages we’d visited. There were real businesses and facilities oriented to tourists, including a museum, a hotel and a number of shops. We got out in front of an enormous factory building and proceeded to head inside. Although idle, what we saw inside didn’t square in any way with the Amish we’d just visited — not even with those who operated the furniture factory.

This factory was where Amana appliances were made. Although I was familiar with the Amana brand name, I’d never actually associated it with the town of Amana, nor with the Amish people. The Amana Refrigeration Corporation was founded way back in 1934. More recently, the brand had branched out, producing a full line of kitchen appliances. Arrayed before us were enormous assembly lines with refrigerators, dishwashers and stoves in various states of assembly. When our guide took us to the area where microwave ovens were being assembled, I was astounded. I’d forgotten that it was Amana that had introduced the Radarange, with its space-age touch controls.

I only knew one person whose family owned a Radarange. It was my friend, Mitch Townsend, whose father owned a chain of dry cleaners. Mitch was a good friend, but we traveled in different circles. His family was loaded and could easily afford a $500 appliance that cut cooking times by three-quarters. You could get a decent used car for that. No, a Radarange wasn’t something most people could afford. Yet they were being assembled in a factory by men whose wives baked their bread from scratch. What a contrast!

After touring the factory, we walked to a communal restaurant where we were to be fed a traditional Amish meal. It was already after 3:00 and I was beyond starved. They sat us at long tables and placed large serving dishes in front of us, filled with a variety of traditional foods. We had meatballs, fried chicken, mashed potatoes, green beans, fresh rolls and a host of other dishes that we passed around so that each of us could take a little of everything. The food was quite tasty, but nowhere near as nice as the fare I’d enjoyed at the Pennsylvania Dutch restaurants we had in Indiana.

I was a bit disappointed to begin with, as I suspected most of us were, and I didn’t appreciate the rather stoic behavior of the women who served us. They never smiled, hardly ever talked and behaved as if they didn’t want us there. In retrospect, they probably weren’t happy to be serving a boisterous group of teenagers on what was supposed to be a day of prayer. Regardless, I thought they should’ve treated us with respect.

When they served us dessert, they brought us each a slice of Dutch apple pie… and they set down a piece of paper next to it for each of us. Turning it over, I was surprised to see that it was a dinner check for $4.95. Everyone seemed to be upset as we all saw the checks at the same time. Flagging someone down, I asked, “Excuse me, but we already paid for dinner. We were told that dinner was included as part of the fee we paid.”

“I’m sorry, honey, but whoever told you that was mistaken. Each diner is responsible for paying for their own meal. If you were told otherwise, you’ll have to take it up with the tour operator.”

I was fuming. We all were. I was almost too angry to eat the apple pie, but I was paying for it, one way or another. Actually, the apple pie was the one thing that was exceptional, but it didn’t make up for the unfriendly service or the fact we were being made to pay for a meal that wasn’t nearly worth the price — a meal we’d thought we’d already paid for. Hell, for $4.95, I could’ve enjoyed a decent meal in one of the best restaurants in Indianapolis.

A woman came around to collect our payments and I reluctantly paid with a five. I got back a nickel in change, which I left on the table as a tip that was overly generous for the service received. I wasn’t the only one who left a one-percent tip. Most left nothing.

The moment we got back to our dorm, Paul and I, along with several of the others who’d been on the trip, marched right up to the floor supervisor. We told him what had happened and he insisted that dinner was included in the price of the trip. He asked if we had proof we’d been asked to pay, but none of us had thought to ask for a receipt. The only evidence I had was my empty wallet. At least he agreed to look into it.

On Monday we learned that the tour operator insisted dinner had been included and that we must be lying. Obviously, someone had pocketed our money. In the end, the tour operator admitted no wrongdoing and we were each given a voucher for twenty percent off our next tour, good for a year. Yeah, like I’d ever trust them again, even if I came back.

<> <> <>

I’d made a lot of progress but was having difficulties with my graphic print subroutine. When I met with Dr. Ellis on Tuesday over pizza, he suggested I table that effort for now, leaving it until the end to do if there was still time. I asked if I could stop attending the class on state machines, so I could focus more on my research project. A lot of the class time was spent going over the lab, which I wasn’t attending anyway. Besides which, now that I understood it, I could learn more from rereading my copies of Knuth’s books. Dr. Ellis was fine with that. I therefore spent yesterday afternoon working on the remaining two programs, before tackling the final one, the Fourier program.

When I wasn’t at my desk in the office I shared with Glen, or punching cards or trying to figure out what I’d done wrong that made my latest submission croak, I spent many of my waking hours, and some sleeping ones too, thinking about the Fourier program. Not that I didn’t still eat with my friends or shoot the shit with them, as Greg liked to say. However, my friends were beginning to comment that I was only half there. Only Paul was able to take my mind off my work. I still couldn’t get enough of making love to Paul.

The concept of the Fourier transform is simple. It converts a waveform from a function of time to one that is a function of frequency. Anyone who’s used a graphic equalizer can see the benefit of manipulating signals in the frequency domain. Complex differential equations in the time domain become simple algebraic expressions in the frequency domain. Fourier transforms make it easier for electrical engineers to solve complicated problems and hence to design things. However, there’s a big difference between the theory of the transform, which assumes infinite time, and numeric solutions that operate in the real world.

An ordinary sine wave at a single frequency transforms to a singularity at that frequency. A sine wave, truncated, sampled and quantized into a series of numbers, yields a vastly different result. I found entire books written about these things. At least I didn’t need to start from scratch. There were many existing algorithms to choose from. Given the time constraint, the most important thing was to keep it simple. Something told me my program was gonna take a stack of hundreds of cards.

<> <> <>

Wednesday, July 19, 1972

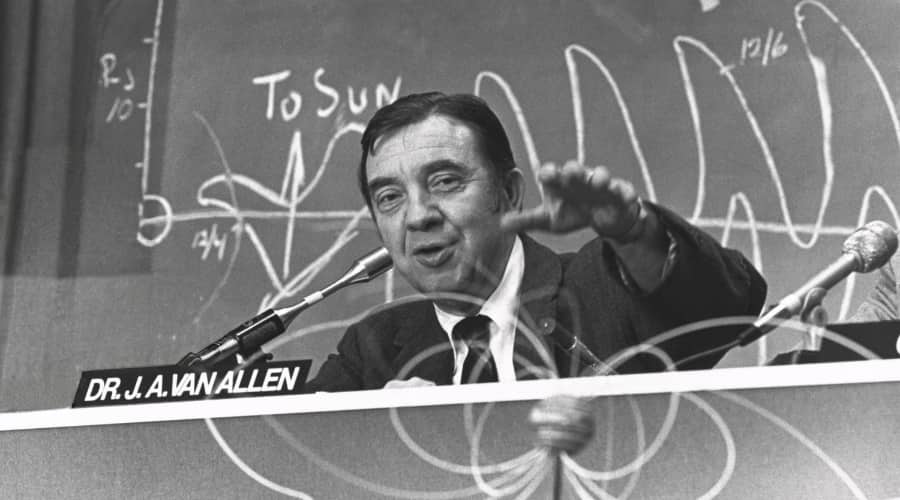

My friends and I were much more animated than usual as we headed across the river after dinner. We were on our way to Schaffer Hall for the weekly research seminar, but this one was different. The speaker tonight was James Van Allen, the chairman of the Department of Physics and Astronomy at The University of Iowa. He’d virtually founded the field of magnetospheric physics and was instrumental in the development of America’s space program. In 1960, he was Time Magazine’s Man of the Year. He discovered the vast radiation belts that surround the earth that bore his name. He was a legend on campus and a paragon of the scientific community.

James Van Allen was everything I aspired to be. I might not yet know what I wanted to do with my life, but I aspired to greatness nevertheless. I might not be a genius like Paul or have the opportunities afforded to kids like my friends back home, Andy Trainer and Mitch Townsend. Still, I knew I was fortunate to have an analytical mind and that I picked up knowledge much more quickly than most of my classmates. No matter how difficult the path ahead, I was determined to make something of my life.

“I wonder how someone of his fame ended up here,” Gary mused as we walked.

“He was born here,” Kyle pointed out. “He grew up on a farm near Mount Pleasant.”

“Where the fuck’s Mount Pleasant?” Larry asked. I couldn’t help but notice how much more colorful our language was becoming as we spent more time away from our parents.

It’s a small town in the southeastern corner of the state,” Greg replied. “According to his bio, he went to college there too. He got his undergraduate degree from Iowa Wesleyan College…”

“I never heard of Iowa Wesleyan College,” Brandon interrupted.

“I don’t think it exists anymore,” Greg said. “It was located in Mount Pleasant. Anyway, he got his Ph.D. right here at the University of Iowa and then he was a Carnegie Research Fellow.”

“At Carnegie Mellon?” I asked.

Shaking his head, Greg replied, “I don’t think there was any connection except for the name. The Carnegie Institution for Science is headquartered in Washington, D.C. Both were probably funded by Andrew Carnegie. Anyway, he was appointed to the National Defense Research Committee and when World War II broke out, he was transferred to the Applied Physics Laboratory at Johns Hopkins. He was a commissioned officer in the Navy, achieving the rank of lieutenant commander.”

“So how’d he end up here?” Steve asked.

“He returned to APL after the war and became involved in upper atmospheric research. Then he became a research fellow at the Brookhaven National Laboratory. I don’t need to tell you, that’s a big deal. A year later, in 1951, he was offered the position here.”

“How do you remember all this stuff,” I asked.

“Call it a gift or a curse, but I have a photographic memory,” Greg explained.

“Remind me not to compete against you on Jeopardy,” Larry exclaimed.

“‘Famous Scientists’ for fifty,” Kyle said in a perfect parody of Art Fleming. “Co-winner of the 1962 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, he currently serves as the director of the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory.”

“Give me a break,” Paul responded. “Who is James Watson?”

“Correct!” Kyle replied. “And now, the Daily Double.”

We were approaching Schaffer Hall and so our silly chatter came to an end as we took our seats in the lecture hall. We’d left early, hoping to get front row seats, but we weren’t the only ones who’d had that thought. We ended up in the second row, which was still within spitting distance of the stage, as my mother liked to say. With time to kill, I zoned out and thought about my Fourier program as my friends chatted among themselves. If anything, the room was much louder than usual, as everyone anticipated the appearance of the world-famous scientist.

Right on time, Dr. Ratcliffe walked into the lecture hall. With him was a rather ordinary-appearing, older man. I could have easily passed by him while walking around the campus and never known it. I’d read he was something like 57, which was getting up there. Then again, some of the top scientists in the world worked into their seventies and even eighties. Albert Einstein was still at it when he died at the age of 76. He didn’t die from old age, either — it was from a ruptured aneurism. That was the year before I was born.

Dr. Ratcliffe gave a lengthy introduction, and then Dr. Van Allen began to speak. He wasn’t at all what I’d been expecting. For one thing, he didn’t bother using the microphone. Rather than stay behind the lectern, he walked around on the stage and spoke loudly and clearly enough that everyone could hear.

He told us his story — about growing up on a farm and taking an early interest in the farm machinery and electrical devices. He told how he finagled his parents into subscribing to Popular Mechanics and Popular Science, and about how he spent his time in town at the library. All of this was listed in his biography, but Van Allen made it come alive. He told us not only what he did as a boy and a young man, but why.

He told us an anecdote about building his own Tesla coil and how it horrified his mother when she saw it making sparks and causing his hair to stand on end. However, he was grateful to have had understanding parents who encouraged his interests and let him follow a different path from their own. He related how having a small private college in town afforded the opportunity to further his education at an early age.

Van Allen told us all about his pursuits, meeting President Roosevelt, working with some of the top scientists in America, including the German rocket scientist, Wernher von Braun, considered the father of the American space program. He spoke of serving in the Navy and the humbling experience of being in command when so many lives were on the line. He credited the Navy with having broadened his horizons and how it prepared him for the greatest challenge he’d ever faced, next to marriage, becoming a department chair.

Van Allen told one humorous anecdote after another, entertaining us as no one else ever could. He went on to talk about the science behind his research and of the wonders of outer space. He spoke of the immense work still to be done, of the possibility of traveling to the stars and the potential to discover other intelligent life.

We were all mesmerized by his talk and could scarcely believe it when it came to an end. He’d spoken for an hour, yet it seemed like only fifteen minutes at most. He opened the session to questions from the floor and took many of them, sometimes expanding his answers into a plethora of additional information. Finally, Dr. Ratcliffe drew the discussion to a close, but invited anyone with additional questions to come to the front of the room.

When Paul made his way to the front, I followed him, rather than returning with our friends. There were a few others and so we waited another fifteen minutes before Paul was able to talk to Van Allen. He began, “Dr. Van Allen, I’m Paul Moore, I’m thirteen and a Junior at Lewis Central High School, in Council Bluffs. The one thing the SSTP has shown me is just how inadequate my high school is, compared to college.

“Here, I’m learning calculus, there, I’ll be taking trig and from what I’ve been told, it isn’t even the right kind of trigonometry. I’m in all advanced placement courses, but that still won’t make up for what I could’ve been taking here if I were in college. I know I need to finish high school in order to go to college, but it all seems like such a waste.”

Turning to Dr. Ratcliffe, Dr. Van Allen asked, “Did you explain to them about the opportunity for continuing their education here?”

“I haven’t gotten to that, yet,” the SSTP director replied.

Turning back to Paul, Dr. Van Allen asked, “Paul, what if I were to tell you you could start college in the fall as a freshman at the University of Iowa?”

“It would be my dream come true,” Paul answered, “but is that even possible?”

“Oh, it’s more than possible. When you applied to the SSTP, you were applying for admission to the University of Iowa as well. Most of the kids enrolled in the SSTP are more than capable of college work and for some of them, the need to finish high school is unimportant, particularly if they can get a bachelor’s degree in three years, at the age of nineteen or, in your case, sixteen.”

I could sense Paul’s rising level of excitement, but there had to be a catch. I asked, “Won’t he feel out of place as a thirteen year old among eighteen year olds? I asked.”

“I’m already a freak at my high school,” Paul countered. “College couldn’t be any worse.”

“Paul, could I ask you what areas of study interest you?” Dr. Van Allen asked.

“Astrophysics, full stop,” he replied. “I live near Offut Air Force Base and the Strategic Air Command. High altitude balloons and experimental aircraft are a fact of life around Omaha. I’ve always been fascinated by them, but they just scratch the surface, barely getting to the threshold of space. I want to be a part of exploring what’s out there, beyond the Van Allen Radiation Belts. One of the reasons I was so interested in the SSTP was because of you.”

It suddenly dawned on me that for all the time we’d spent talking about our lives, current events and our hopes and dreams, we’d never talked about what we wanted to do with our lives. Fuck, I’d had my tongue down his throat and his dick in my mouth. I wasn’t sure what I wanted to do with my own life just yet, but I’d never even thought to ask Paul what he wanted to do with his.

Was our relationship that shallow?