The Binary Planet

A Science Fiction Adventure by Altimexis

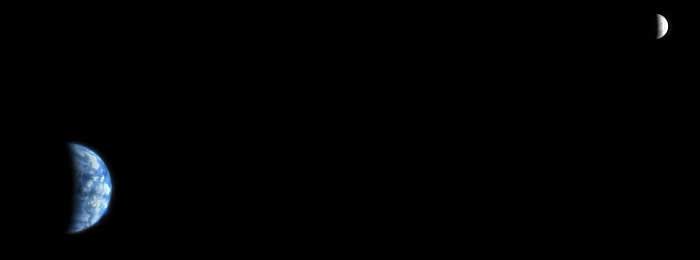

The binary system of Earth and its moon as seen from Mars © NASA

Part 1 — Escape

Had it really been a year? A year of living alone on this desolate red rock — a year of not even hearing my name, Lansley? Yes it had been a year — well, what passes for a year on this planet anyway. At least the length of the day is about the same as back home, but it takes more than four times as along — more than 668 days — for this place to complete a revolution around its star. Back home I’d be 34 years old, but here I was only 8. Either way I was just a kid — a very lonely kid.

I may be just a kid, but oh what I’ve seen in my short life. I barely remember what life used to be like back home. My parents told me what life was like before the invasion — before the Cerenians came. Sankar was only eight years old — Loran years, that is — and my other parent, Warskin, was nine when the trouble began. They were only toddlers. We had lived a peaceful existence on Loran — the last war had been fought nearly 350 Loran years before I was born; no one could even conceive of the need to fight for one’s freedom.

When our people first ventured into space, we’d assumed that the notion of a war between planets was the stuff of science fiction. The realities of space travel, in which it could take several lifetimes to reach the nearest habitable planet, made the conduct of war totally impractical. Why set off to fight a war when it would end up being your grandchildren that would be left to fight it?

That was before we encountered the Cereneans. For one thing, they had a very long lifespan and were exceptionally patient. It didn’t matter to them that it took over 450 Loran years to reach our world — not when they lived to be five times that age. Further, they could tolerate longer, more intense periods of rapid acceleration than we could. At best, it took us two Loran years to accelerate to near the speed of light, but the Cereneans could do it in half the time without affecting their physiology. Over the course of a 100-year journey that might not add up to much, but it was the competitive edge they had over us that made it nearly impossible to escape their clutches.

We were totally unprepared to fight them. They had weapons whereas we had none, and we had no technology to protect our spaceships from attack. The Cereneans were able to pick our ships off like ducks in a shooting gallery. They were able to subjugate a planet of more than ten billion people with a force of only fifty thousand souls. Loran was theirs after just forty days and they wasted no time in exploiting our resources, and enslaving us.

To this day I cannot fathom why they went to war with us. The galaxy is overflowing with natural resources. There are plenty of lifeless rocks out there with more mineral wealth than anyone could ever use. Life, however, is a precious commodity. Fewer than five percent of all stars harbor planets capable of supporting life and, of those, only a fraction of a percent actually do contain life forms of any kind.

The Cereneans were the first intelligent civilization we had encountered besides our own and we now know that the Cereneans have encountered — and subjugated — only two other civilizations besides ours. That’s only four intelligent species out of thousands of star systems explored so far. Why did the Cereneans feel the need to dominate every intelligent species they encountered? Wouldn’t it have been better to trade knowledge with one another - to allow us to continue our natural growth for their own benefit?

Too late we realized the Cereneans didn’t think like we did. To them, interacting with other intelligent species meant dominating them and, at that they were swift, ruthless and struck without warning.

No longer were we allowed to attend school, to travel as we pleased or to practice our religion. Everyone from the oldest members of our society down to kids as young as my parents had been were told what they had to do and how they were expected to serve the empire. To fail in our responsibilities in any way brought swift punishment. Kids they’d gone to nursery school with were gunned down, right in front of their eyes for nothing more than crying when they were supposed to be working. Life on Loran had become a living hell.

One day when I was thirteen Loran years old, my parents took me away in the middle of the night. I did not really understand what was happening — after all, I was just thirteen and would have only been in the first grade if the Cereneans allowed us to go to school — and only later did I learn the truth of what my parents had done, and were doing for our future.

Unbeknownst to me at the time, they were in the Loran resistance movement. Their objective was simple enough, but it was not an easy one. They were to try to escape in a Cerenean ship and find a new home for us. Once they had established an outpost on some distant world, free from the influence of the Cereneans, they would send back a coded message revealing our coordinates so that others might follow.

Because it was much less likely the Cereneans would pursue a small ship with a handful of occupants, we departed alone, just the three of us. Other families departed as well that night, but only six attempts could be made at a time. A larger number might have improved the chances of success, but the Cereneans would have undoubtedly noticed a large-scale operation and the chances of success without loss of life would be much lower. The preservation of all life was important to us.

Armed with access codes and Cerenean weapons obtained from the Cerenean ‘fifth column’, my parents quickly located a small spacecraft and dispatched its crew. That was the easy part. Although the proper access codes allowed them to control the ship and launch into space, it didn’t take long for the Cerenean authorities to discover that our flight wasn’t authorized. In mere moments we were under attack. Fortunately, our ship was well shielded and well armed, but my parents concentrated on evasive maneuvers, using the weapons only to slow our pursuers down. A full-scale attack would have only resulted in a response in kind and we would have been blown to bits in no time. Obviously the Cereneans wanted their ship back intact if possible and, in retrospect, they probably wanted us alive, the better to make an example of us.

Skimming the surface of our star, we ultimately managed to throw their sensors off and eventually they broke off the attack. They undoubtedly assumed we’d crashed into our star and burned ourselves up in the process. Unfortunately, the stellar radiation severely damaged a number of our ship’s systems, some of them beyond repair. However, we didn’t discover the extent to which the ship was damaged until we were well underway.

Even though I was only thirteen at the time, I will always remember my parents’ conversations in the days following our escape from Loran.

“Navigation is off-line,” Sankar explained to my other parent, Warskin. “Propulsion is functional as are long-range sensors, but life support is marginal at best.”

“How marginal is marginal?” Warskin asked.

“It could fail at any time but, even if it holds up, I don’t think we can survive more than ten years, maybe fifteen at the most,” Sankar replied.

“Shit, that would still leave us within Cerenean space!” Warskin protested.

“Actually, we may be able to double or even quadruple our range,” Sankar countered.

“How so, Sank?” Warskin asked.

“The propulsion system on this ship is much more robust than that on a Loran ship,” Sankar started to explain. “Our ships are designed only to accelerate to and cruise at near-light speed, and then decelerate at a similar rate. That’s four years of propulsion. This ship can operate under continuous propulsion for more than a hundred years.”

“But how does that help?” Warskin asked. “We can’t go any faster than the speed of light.”

“From the vantage point of the outside observer, that’s certainly true,” Sankar agreed, “but as we approach the speed of light, relativistic effects begin to kick in. The passage of time will slow for us. From our vantage point, relative to our destination, wherever that might be, it will seem as if we are able to accelerate to several times the speed of light. By slowing the passage of time, ten years on this ship could become twenty or even sixty if we push it.”

“Ah, I see exactly what you’re getting at,” Warskin exclaimed. “If you figure it’ll take us two years to accelerate up to light speed and another two years to decelerate, that still leaves six years during which we can slow the passage of time on board by continuing our acceleration. But how do you figure twenty or sixty years in total?”

“We’re used to accelerating at the rate of Loran’s gravitational acceleration, but this ship is designed to operate at twice that.”

“But we are not designed to live in a two graviton environment,” Warskin countered.

“No, but we can survive 1.5 gravitons long term if we have to,” Sankar explained. “If we do that, we can accelerate and decelerate to and from light speed in only three years instead of four, and the slowing of time will be even more profound at the higher acceleration. The only question is where we should go.”

“I had a number of potential destinations scoped out,” Warskin related, “but the closest one is some eighty Loran light years away.”

Shaking his head, Sankar responded, “Chances are very slim we could make it that far. I wouldn’t want to chance it. Are there any prospects a little closer to home, but not too close?” he asked.

“There is a binary planet system around Arkenza, about 56 Loran light years away. Arkenza 3b is a small, lifeless rock that lacks any atmosphere or useful resources. Arkenza 3a, on the other hand, is a viable option. It’s larger than Loran with a gravitation field of 1.5 gravitons. The atmospheric pressure at the surface is 2.8 Loran atmospheres, but the oxygen concentration is only 21%, so the partial pressure of oxygen is nearly the same. The remainder of the atmosphere is primarily nitrogen so, although it’s marginal, it should be capable of supporting us except…”

“Except what, Warskin?”

“Except that the carbon dioxide concentration is much higher than I would expect for a planet of its size and composition. We already know it more than likely harbors life — photosynthesis is virtually a prerequisite for such high concentrations of oxygen — but photosynthetic processes almost always soak up virtually all the carbon dioxide around. As we ourselves learned the hard way, however, it’s only too easy to overcome the photosynthetic capacity of a planet by burning fossil fuels. My concern is that Arkenza 3a might harbor a pre-fusion society.”

“That’s absurd,” Sankar challenged. “Life is an extreme rarity, and Arkenza is too young. Intelligent life evolves late in the lifecycle of a star if at all. Besides, wouldn’t we be able to detect their communications signals?”

“With a pre-fusion technology, their ability to focus an electromagnetic beam would be crude at best,” Warskin explained, “and it’s unlikely they’d focus anything in our direction in any case. Conventional electromagnetic communications at this distance would be buried in the general background radiation of space. We’d never be able to detect it from here.”

“Well for better or worse, I don’t see that we have much choice,” Sankar countered. “Unless you have some place else to suggest, that is. Otherwise, I think we should set course for Arkenza 3a and hope for the best. If it turns out that Arkenza 3a is inhabited by intelligent life, we’ll either find an out of the way rock to settle on while we attempt to repair the ship, or we’ll hurl ourselves into their sun. The last thing we want to do is to contaminate their culture if they’re not ready for space travel, and we certainly don’t want to take a chance on leading the Cereneans to their world.”

Sighing, Warskin replied, “I agree completely, Sank. I don’t think we have another choice.”

And so we laid in a course for Arkenza 3a and began our journey into the future. Although I scarcely understood what my parents had been talking about at the time, I very quickly learned what it meant to travel at 50% greater than normal gravitational acceleration. Man, I felt like a total weakling!

We were all pretty banged up from our fight to escape the Cereneans, but it soon became apparent that Warskin was in much worse shape than Sankar and I. About two days into our journey toward Arkenza, Warskin started acting funny. He was slow, confused and unsteady on his feet. Sankar noticed it too and kept asking Warskin if he was OK. Warskin swore he was alright but, by the end of the day, he could barely remain awake.

Finally, Sankar convinced Warskin to let him run a medical diagnostic on him. We didn’t have a doctor on board, but we had a complete medical kit, with a portable MRI and a medical robot.

Sankar completed an MRI scan and then lovingly cradled my other parent. “War, you’ve got a sub-cranial hematoma. The diagnostic computer says you probably have an arterial leak and you’ll die if we don’t operate.”

“How bad is it?” Warskin asked.

“The computer recommends we get you to a hospital for emergency surgery,” Sankar answered, “but obviously that’s not possible. The medical robot can perform the procedure but, without the equipment of a full operating suite, the chance you’ll survive is less than fifty percent.”

“And it’s a Cerenean robot at that,” Warskin added, “but what choice do we have?”

I’ll never forget seeing tears in Sankar’s eyes as he told my other parent, his mate of twenty years, that he might die. Even I understood the implications and I cried, too.

“If I don’t make it,” Warskin went on, “promise me you won’t blame yourself. We had to escape, and I have complete confidence that you’ll be able to carry on the mission, even if I’m not by your side. Some things are worth dying for but please don’t blame yourself. I went into this willingly. I don’t think I need to ask you this, but take good care of Lansley. He’s my life, too.”

With fresh tears in his eyes, Sankar said, “I promise, War, but you’re going to make it. I know you will.”

The medical robot performed the operation but Warskin’s heart stopped twice during the procedure. Although the robot got his heart going again both times, Warskin never woke up after it was all over. He stayed in a coma for five days as we continued our journey, and then his heart just stopped and the robot couldn’t get it started again.

Sankar and I cried our eyes out for the next several weeks. We both loved Warskin so much. He was the love of Sankar’s life and the only parent I’d ever known besides Sankar. No matter how long I live, I will never forget the somber mood we shared as we jettisoned Warskin’s lifeless body into space.

“It’s just you and me, Lans,” Sankar said as Warskin’s body disappeared from sight. “Together, we must carry on. It’s what Warskin wanted us to do.”

Life wasn’t the same without Warskin, but no amount of crying could ever bring him back. Sankar and I continued our journey to Arkenza 3a, which was hopelessly far away. There wasn’t a whole lot to do on the journey other than to maintain the hydroponics bay, which provided our food and revitalized our air. Even then, most of the work was automated, so that left us with a lot of time on our hands, much of which was taken up by my education.

As the days became months, and the months became years, I took on more and more responsibility and a greater and greater share of the work as I matured. I was still just a kid but Sankar treated me pretty much as an equal, especially once I reached my twenty-fifth birthday in Loran years. Back home twenty-five is a milestone. There is usually a big ceremony and you receive lots of gifts. Twenty-five is also the point at which most of us enter puberty.

Going through puberty without any friends to share the experience left me feeling horny as hell. Without any connection to our home world, my access to, um, stimulating material was severely limited and I was forced to rely on my imagination when I got myself off. My favorite fantasy was getting it on with an alien from another planet. I imagined what it might be like to rub a forniculus that was three times as large as any a Loran had, or to taste the sweet nectar of a being from another world. Yeah, I got off plenty thinking thoughts of such things.

One year later we were on the deceleration phase of our journey, having gone well past the halfway point. If things went as planned, we would land on Arkenza 3a in just a little over four Loran years. We would be there before I even turned thirty and I was excited at the prospect of what we might find.