Sing to the Lord

by Alan Dwight

alantfraserdwight@gmail.com

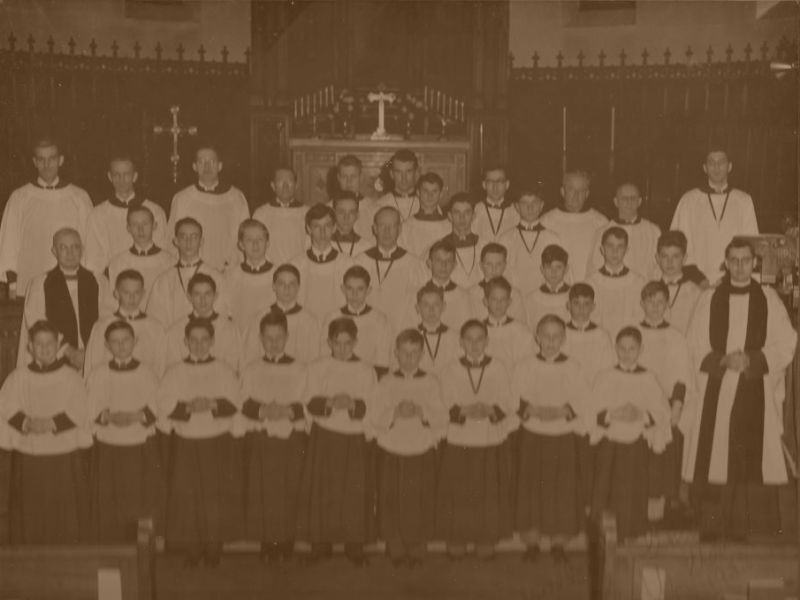

I was sitting in my recliner, ruminating. When one reaches the age of 80, sometimes there isn’t a lot to do other than ruminate. Oh, I watch an occasional movie on TV; I sometimes watch the Red Sox; I usually read a few hours a day. But this afternoon, I was sitting in my recliner, listening to the rain beat a gentle tattoo on my roof while music played quietly on my computer. Ruminating. My gaze moved lazily around the room and landed on a framed photograph on my wall. It was a picture of my cathedral boychoir dated January, 1953.

I struggled up from the chair, walked over to the wall, retrieved the picture, and returned to my chair. I had no trouble finding myself in the picture. I was standing two over from the dean of the cathedral, who was easy to find at the left of the group because he was wearing a stole. I was wearing a purple ribbon around my neck from which hung a choir cross. The cross was not visible in the picture, and I was very sad that I could no longer find it. The crosses were designed for the cathedral by a local silversmith. They represented leadership, good attendance, and length of service.

When the picture was taken in 1953, I was 14 and I had sung in the choir since the age of 10. I continued to sing in the choir until I graduated from high school and went away to college.

Now, at 80, as I looked at the picture, I wondered what had become of all those boys. Most of them I couldn’t even name. The boy I had felt closest to had left the choir when his voice changed before the picture was taken. All these years later, I was still sad about that. I wondered where he had gone and what he had done with his life.

I finally dozed off, still thinking about that choir and my life in it. Still ruminating.

********

I stood nervously before a man, Mr. Reynolds, who was at the piano. Looking at me, he asked, “How old are you, Michael?”

“Ten, sir,” I replied.

“Can you read music?” he asked.

“Yes, sir,” I answered.

“Well, let’s hear you sing a bit,” he said. “Let me hear you sing this on the syllable ‘ah’.” He demonstrated, beginning on the A above middle C and playing and singing from A down to D. I sang. The starting notes ascended by half steps until we got to D. Then we did it again starting on A and descending by half steps. After that he had me sing rising and falling arpeggios on do-mi-sol-do-sol-mi-do, the arpeggios climbing by half steps until I sang a high A.

Finally, he said, “Well, Michael. I’ll accept you as a probationary chorister and we’ll see how it goes for a little while. Todd,” he said to the boy behind me, “Michael will be number 23 for now. Show him where we keep the music and have him sit next to you.”

Todd showed me how to find my music from among the cubbies lining one wall and then directed me to sit next to him on the end of the first row of boys.

Todd was a year older than I. He had heard me sing at a scout talent show. I had sung “The Big Rock Candy Mountain,” having learned it from a recording by Burl Ives. I’m not sure how Todd decided that my singing a folksong qualified me to sing in a boychoir, but he had. His mother called my mother and made arrangements; on Thursday, she had picked me up after school and taken me to the choir rehearsal.

So there I was, in the Episcopal cathedral choir room, sitting next to Todd and having no real idea of what I was doing. Mr. Reynolds called the group to order and we went through several vocal exercises to warm up. Then he had us look up the hymns for Sunday in our hymnals and sing a couple of verses of each. Some of them were unfamiliar to me, so I struggled a bit at first, but usually by the second or third verse I had figured out the soprano line.

After the hymns, he had us turn to the back of the hymnal, where there were Anglican chants. Having always attended a Congregational church, I had never heard an Anglican chant. The music for four different settings of the chant was at the top of the page. Below that, were the words. I learned later that the marking above and between the syllables was called “pointing.” The pointing showed how the words were supposed to fit with the music. Mr. Reynolds played the chant through once and then the boys began to sing. While I could follow the words, trying to figure out the pointing, or I could follow the tune, I had great difficulty fitting the one with the other. Sometimes the boys sang several syllables on the first note before moving on to the others. Sometimes they sang two or three syllables on another note before moving on to the last note. At first, I had absolutely no idea what was going on, so I spent my time trying to figure it out.

After that, we moved to pieces of music which were in our folders. We rehearsed one for a while, with Mr. Reynolds sometime stopping us and pointing something out or having us repeat a passage. We did this for several anthems before it was time to go.

I put my music back in cubby 23. Before I followed Todd outside, Mr. Reynolds called to me and asked me how things went. I was pretty sure he already knew that because he had glanced at me many times throughout the rehearsal. I told him that the hymns and the anthems went okay but I had trouble with the Anglican chant. He smiled and told me not to worry, that I would soon catch on and that we sang those chants often. Then he reminded me to be at rehearsal Friday night at seven and let me go.

I followed Todd out the door to the quadrangle, where Todd’s mother was waiting. She asked how I had done, and I told her fine and that I was a probationary chorister, although I didn’t know what that meant.

Todd must have seen my confusion because he said, “It means that you’re kind of on trial for a little while to be sure that you can fit in. You’ll have no problem and when your probationary period ends, you receive your cotta.”

“What’s a cotta?” I asked.

Smiling, he said, “There are two parts to our robes. The first part is called a cassock, and it covers us from our shoulders down close to our ankles. Over that goes a white cotta which hangs down to our waist. So for the first few weeks you’ll wear only the cassock, and then you’ll be given the cotta to go over it. By the way, in case nobody tells you, you should wear polished shoes, not sneakers, and a white shirt and dark tie on Sunday.”

When we arrived at my house, I went in through the kitchen door. My mother asked me how it went, and I told her enthusiastically what had happened, reminding her that I had to be at rehearsal from seven to nine the following evening.

My father drove me to rehearsal Friday evening. When I went in, I found general chaos, which, I soon discovered, was typical. In addition to the choirboys there were men who sang tenor or bass. The boys were divided into sopranos, like me, and altos. Unlike English choirs, which I traveled to England to hear much later, we used boy altos instead of countertenors, and I learned to like that sound first. The first time I heard a boychoir with countertenors I really didn’t like the sound and it took me years to get used to it. But that’s getting ahead of my story.

Much as it had on Thursday, the rehearsal proceeded through the hymns and chants before moving to the anthems. When we rehearsed the chants, I did figure out a bit more about the little marks between and over some of the words, which showed how many syllables to sing on one note. I held my own in the anthems. Unlike the Thursday rehearsal, the Friday one stopped in the middle while the men took a 15-minute break so they could go into another room and smoke. Oh yes ̶ in the 1950s more people smoked than not. My father smoked a pipe and had done so since his teens. I was grateful that at least the men didn’t smoke in the choir room.

When the rehearsal ended, a little after nine, I went out to the quadrangle, where my father was waiting to take me home. It was after 10 o’clock when I fell into bed and immediately went to sleep.

I should explain about the quadrangle. Behind the cathedral there was a grassy rectangle surrounded by buildings with a driveway and sidewalk around it. On one side were the cathedral and a museum. The back of the public library was on another side and on the other two sides there were three more museums which had entrances on the quadrangle. Sometimes, after Thursday rehearsals, some of the boys played around a bit on the grass until Mr. Reynolds shooed them away, but I didn’t do that until later in my career because I always had a car waiting for me.

I didn’t want any of my friends in the neighborhood or at school to know about my singing in the choir, because I first wanted to be sure that I got in. So the next day, I played with my school friends, Allen and Teddy, but said nothing about the choir.

On Sunday, I arrived a little before 10 for the 11 o’clock service. There was a woman there who told me she was the “Choir Mother.” She showed me my locker, number 23, and helped me find a cassock which fit. It was purple and she explained that we wore purple because we were a cathedral choir. I retrieved my anthem for Sunday and my hymnal before sitting in my seat. The other boys and men, all robed, came in and sat down until the full choir was present. We had a warm up and worked on the anthem some before it was time to line up and process into the church. Then we waited in a little vestibule where we were joined by the dean of the cathedral and a couple of other clergy, as well as a man who carried the cross at the beginning of the procession and two boys called acolytes who carried tall candles.

Soon the organ began to play the processional hymn and we walked in singing, following the cross and the acolytes. This was all new to me, and I was so afraid I’d do something wrong that my heart was pounding in my chest. We processed down the side aisle and then up the middle aisle to the choir loft. When we got to the beginning of the choir pews, Todd turned to his left and went into the first one with me following. That put us nearest to the altar. From there I took my cues from Todd, standing when he stood, sitting when he sat, kneeling when he knelt.

In those days, most Episcopal churches only had communion on the first Sunday of the month. The services on other Sundays were Morning Prayer. We sang Anglican chants on the Morning Prayer Sundays. Of course, in the middle of the service, there was a sermon which I couldn’t have followed even if I wanted to because the pulpit was around the corner from the choir loft. At the end of the service I followed Todd as we recessed out again. Once in the vestibule, the dean chanted a short prayer and we all sang an amen.

At the end of the month, Mr. Reynolds gave each of us an envelope with some money in it. That was the first I knew that we got paid, that we were professionals. My envelope had a quarter in it. It wasn’t much, but I could buy an ice cream sundae with it. Occasionally, over time, I received little raises. By the time I left the choir I was making more than $5 a month.

In the weeks that followed, I looked forward to the rehearsals and the services. There was something about being part of an all-male group which I really enjoyed. Even at the age of 10, I was finding myself rather attracted to some boys. In particular, David Walters, who I thought was especially cute, attracted me from the first day. He had dark hair, which he wore longer than most boys did in the late 1940s. He let it hang down over one eye, and his eyes, which were dark like his hair, sometimes sparkled with mischief. He had a cute nose, which turned up a little, and a heart-stopping smile. He was two years older than I and clearly the leader of the boys, even though some of them were older than he was.

Unfortunately for me, he sat at the other end of our row nearest to the congregation, and I seldom had a chance to say anything more than hello to him. I used to spend time trying to figure out how I could get to know him better, but I had little success.

In time, I received my cotta with a little ceremony at the altar rail. From then on, I was a full-fledged member of the choir.

As I mentioned, we couldn’t hear the sermons even if we wanted to, so the boys usually played paper-and-pencil games while the sermons droned on. Hangman was a favorite as was tic-tac-toe. But the most favorite was Battleships. I don’t know if the manufactured game of Battleships was around then, but it didn’t matter as we drew grids on paper, placed our ships, and played quietly.

One Sunday, I suppose it was the first Sunday of the month as it was a communion service and the bishop was present, most of us played our usual games, but I noticed that David was reading a comic book which he had smuggled into the church under his robe. At the end of the service, we recessed as usual with the clergy coming behind us. After we got into the vestibule and the bishop had said a closing prayer followed by our sung amen, he held up a comic book and asked if any of us had lost one. Apparently, the magazine had fallen out of David’s robe into the aisle between the two sides of the choir loft. The bishop had scooped it up and brought it with him. For a moment, nobody said a word, but finally, David held up his hand and stepped forward. “Isn’t it lucky you sing so beautifully?” the bishop said, handing David the comic book. Blushing furiously, David thanked him and accepted the book. Mr. Reynolds never said anything about the episode, but that was the last comic book to make it into the choir loft for a long time.

Since I had attended a Congregational church, I knew little about the Liturgical Year. I had joined the choir shortly after Christmas, and while I knew about Christmas and Easter, Lent was totally new to me. Hymns like “Forty Days and Forty Nights” or “The Glory of These Forty Days” were slower, more solemn, and often in minor keys.

Finally, after six weeks of solemnity, Easter arrived with hymns like “Welcome Happy Morning!” and “Jesus Christ Is Risen Today!” I immediately loved Easter morning for its bright, cheerful music. Easter was the only day when we sang two services, one in the early morning and the other at 11 o’clock. Between the two services, Mr. Reynolds walked us down the street to a cafeteria. I had never been in a cafeteria before, so I was quite excited and took more than I could possibly eat. I managed to sit next to David, who said, “Hi,” to me. I answered him, and then I said, “I really like your voice.” He thanked me and then started talking to the boy on the other side of him. I was rather embarrassed by what I had said; it seemed so ordinary. But I was in awe of him. I was tongue-tied and couldn’t think of anything else to say. When we finished, we returned to the cathedral rehearsal room and went over some things that Mr. Reynolds thought had not gone quite as well as they should have in the first service.

When the school year came to an end, the choir also ended for the summer. I went to overnight camp for a month that summer, another all-male environment except for the nurse. I had a good time, but I never did learn to swim. I started out in a group that was labeled “The Minnows,” and I was still in the same group when I went home.

Late in August I received a postcard announcing the first rehearsals for the choir, and Mr. Reynolds’s wrote on it that he hoped I would return. My birthday had been in May, so I was 11 by then.

At the first rehearsal, I looked around at the other boys, especially looking for David. Todd had decided that being in the choir took too much time and he didn’t really enjoy singing that much. I had moved up to the middle of the front row, so I could occasionally lean across and say something to David. Sometimes, he gave me that to-die-for smile and I felt my heart beating faster.

At the beginning of October, Mr. Reynolds asked me and my mother if I could come to rehearsals on Saturday mornings. I was worried. Wasn’t I doing well enough? Did I need extra practice? When I asked, Mr. Reynolds quickly explained that the Saturday morning rehearsals were for a few boys who were leaders or becoming leaders of the group. After that, I felt better and agreed to go.

The Saturday morning rehearsals went from 10 to 11:30. I always enjoyed them. They were more relaxed than the Friday evening rehearsals because we stood around the piano singing. My father gave me a ride that first morning, but I was to take the bus home. While I had been told a few times not to talk to strangers, there certainly was not the fear then of Stranger Danger. When I wasn’t in choir or at school, I roamed my neighborhood, playing outdoors. There was a vacant lot near us where my friends and I played endless games of baseball. Elementary school in my town went through sixth grade, and I always walked or rode my bicycle the three blocks to school. Later, I rode the two miles to my Junior High.

At the first Saturday rehearsal, in addition to David and me, were Brian Masters and Mark Coggeshall, who were both altos, and Billy Downing, who was another soprano. As we rehearsed, Mr. Reynolds taught us a lot about pronunciation, voice placement, and even how to pronounce Latin. Sometimes, we took turns singing solos, but I always knew that David was the soprano soloist and Brian was the alto soloist. Mr. Reynolds explained that he wanted us to practice the solos anyway so one of us could fill in if either David or Brian was ever sick. Brian had a lovely, mellow voice. David’s voice was simply the best boy soprano voice I had ever heard. To this day I’ve never heard a better one. It had a richness to it that I was to learn was rare in a boy’s voice. Billy, who was younger than the rest of us, had a lovely, untrained soprano voice. Even when I later heard recordings of boychoirs and went to England to hear cathedral choirs, I never heard a voice as good as David’s.

After the Saturday rehearsals, I usually went out onto the quadrangle and played around with the other boys a bit before I took the bus home. One day, Brian, Mark, Billy and I were in the quadrangle when Billy suddenly yelled, “Look out!” Before I had time to react, I was tackled from behind. I fell to the ground with David on top of me, punching my back.

“What’s your problem?” I yelled, crying, because his blows really hurt.

“You’re tryin’ to steal my solos. That’s my problem. But now it’s yours.”

Before I could even process what he was saying, I felt his weight lifted off my back. Rolling over, tears pouring down my face, I saw that Mr. Reynolds had pulled David off me and was holding him from behind, pinning his arms to his side.

I got up off the ground and faced David, who was also crying. “I don’t know what you’re talking about,” I said between gulps and sobs.

David began to answer, but Mr. Reynolds said that the three of us should go back inside. Then he told the other boys, “The fun’s over. You need to go home.” He didn’t let go of David as he headed for the door with me following.

In the choir room, Mr. Reynolds plopped David into a chair saying, “Stay there and don’t move.” I took a chair a couple of places away from David, fearing to get any closer. Mr. Reynolds pulled up a chair facing us and asked, “Now, what’s going on?”

Neither of us said anything. Both David and I were gulping and trying to hold back our sobs. At first, I was afraid that if I said something, David would get me, either then or later. But finally I couldn’t stand the silence any longer.

“I don’t know,” I gulped. “David tackled me from behind and pounded on my back. Then he said something about me trying to steal his solos.”

“Well?” Mr. Reynolds asked, looking at David. David still said nothing.

At last, I looked at David and said, “I’m not trying to steal your solos. I’d never do that. You have the most beautiful voice I’ve ever heard. Why would I try to replace you? I can never do that, and I don’t want to.”

“I just thought you were,” David finally said. “You’ve got a really good voice and Mr. Reynolds was praising you today while he kept criticizing me.”

Mr. Reynolds looked shocked. “Is that what you were thinking, David?” David nodded. “Well, I can tell you that you totally misread what was going on. Yes, I was praising Michael because he’s made a lot of progress and I want to encourage him. But I wasn’t criticizing you. I was just making suggestions. Both of you can keep learning about singing for years to come and you will always need to take and use suggestions. But it never entered my mind that you thought you were being criticized or replaced. That won’t happen.”

David was silent for a time before he turned to me and said, “Sorry I hit you.” He offered his hand which I shook. Then he said, “And I know it was wrong to attack you from behind. Only cowards do that. Can you forgive me?” I nodded and said that I never thought he was a coward.

Mr. Reynolds nodded and asked, “Why don’t I take the two of you to lunch and we can mend fences?” I told him my mom was waiting for me for lunch, so he called and cleared it with her.

We climbed into Mr. Reynold’s station wagon and he drove up State Street to a little restaurant called Friendly’s. We had one in the town where I lived, but the one we went to that day was the original. All my family had been there when they lived in the city, but they had moved to a suburb before I was born, so it was my first time.

We sat at the counter and had hamburgers and milkshakes while we chatted, laughing and giggling. I learned that day that Mr. Reynolds could be quite funny when he wasn’t in choir mode.

When we left, Mr. Reynolds took us home. He went to David’s house first, which was a triple decker in a rather rundown part of the city. David got out of the car, thanked Mr. Reynolds, gave me a friendly little punch on the shoulder, and ran up the steps to the door, disappearing inside.

Mr. Reynolds knew how to get to the suburb I lived in. Once we arrived there, I could give him directions to my house. As we drove, he said quietly, “Don’t tell him I told you this, but, you know, David doesn’t have a very easy life and the choir is kind of an escape for him, so try to be understanding. He needs friends.”

“I like him,” I said, “but he’s older than me and I’ve been just a little awed by him. I’d love to be his friend.”

When Mr. Reynolds dropped me off, I thanked him and went to our kitchen door, where I let myself in. Mom was in the kitchen. I didn’t tell her about being tackled and punched, but I did tell her about going to the original Friendly’s.

Sunday morning, David met me at the choir room door. “Are we okay, now?” he asked. I nodded. “Can we be friends?” I nodded again. He put his arm around my shoulder and a little thrill went through me as we went into the choir room together. He must have said something to Mr. Reynolds, because, from that day on I sat next to him.

David never invited me to his house and I never invited him to mine. Sometimes after Saturday rehearsals we went to lunch together and occasionally to a movie. I’m pretty sure he spent most of his choir money that way. The more I got to know him, the better I liked him.

There was an arcade in town, with lots of games and blinking lights and ringing bells. I had always wanted to go there, but it was in the North End, literally on the wrong side of the tracks, and my mother forbade me from going.

One day, David suggested we go there. When I told him I wasn’t allowed to, he asked, “Who’s gonna know?” I thought about that a bit and then agreed to go with him. It was my first real taste of disobedience and, while I felt guilty, I also felt excited to be going on an adventure with him. Had it been night time, I probably wouldn’t have gone, but it was broad daylight. Of course, nothing happened. We did meet a few older boys whom David knew, and they ragged on us a bit, calling us, “Pretty little choirboys,” and the like, but it was all in good fun and we just laughed it off. We had a good time playing several of the games until our money ran out.

As David and I grew closer, we shared more of ourselves with each other, but I always felt there were things that he never told me, things that made him sad. Perhaps it was his family. He did tell me that he had two younger brothers and a younger sister, but he never told me anything about them. He seldom mentioned his parents at all.

As I said earlier, David had a gleam of mischief in his eyes. I only occasionally saw the actual mischief, but he did like to play pranks. One day he put one of those bells that have a little plunger on top under the pedal of the choir room piano. When Mr. Reynolds began to play the piano, every time he pressed down on the pedal, the bell rang. At first Mr. Reynolds couldn’t figure out where the sound was coming from. When he did figure out and retrieved the bell, he couldn’t hide his smile as all the boys laughed.

Mr. Reynolds was notorious for dismissing the Friday evening rehearsals late. Sometimes, this annoyed the parents waiting to pick up their sons. One night, right at 9:00, we heard an alarm clock go off. It kept ringing and ringing, so, of course, the rehearsal stopped. Mr. Reynolds and some of the men in the choir concluded that the sound was coming from one of the over 500 boxes of sheet music along the wall over our cubbies. It took them nearly 15 minutes to track down the clock. While nobody admitted to the prank, I asked David later if he had done it and he gave me one of his devilish smiles.

One Sunday, before the service, David passed a note among the boys telling us to bring water pistols to the next Thursday rehearsal. I learned later that this was a trick David had begun a couple of years earlier and it had become a tradition. At rehearsal that Thursday, when Mr. Reynolds turned away from the choir towards the piano, twenty or more streams of water shot across the room. Soon, we were all very damp, but we didn’t mind because it was a warm day. Mr. Reynolds, however, pretended to not find it amusing. He grabbed a water pistol from one of the boys and broke it across his knee. Of course, he hadn’t counted on the fact that there was still water in the pistol, and the water ran down his pant leg, occasioning much hilarity among the boys. At that point, Mr. Reynolds couldn’t keep a straight face. He burst out laughing.

Services continued through fall until we came to Advent. Fortunately, that season’s hymns weren’t quite as lugubrious as those during Lent. On the Sunday before Christmas, instead of a Morning Prayer service, we had a special service of Lessons and Carols. I didn’t know it at the time, but the service was patterned closely on a similar one at King’s College, in Cambridge, England. The lessons didn’t vary from year to year, but the readers and the music did. Each reader represented a group in the cathedral. One represented the deacons, one represented the Altar Guild, and so forth. There was one boy from the choir who read the lesson about Adam and Eve. That year and every Christmas until he left the choir, David was the reader. He read the passage flawlessly and with expression, although I’m not sure he or any of the boys who read it after him really understood it.

The service always began with the processional hymn, “Once in Royal David’s City.” The first verse was sung by one soprano, and of course the soloist was David. There were tears in my eyes as we processed, and I had trouble seeing the words to the hymn. Between the lessons there were hymns or anthems. I thought the service was beautiful and looked forward to it each year.

Our next service began at 11 pm on Christmas Eve. It involved candlelight, beautiful greens, and poinsettias. It was another service which enchanted me.

I didn’t get home until after 1 o’clock that morning. Because all the Christmas presents had been put under our tree, I was shooed straight up to bed. I didn’t even get a peek into the living room.

The rest of the year wasn’t particularly memorable except for when I got to sing a duet with David. The anthem, “I Waited for the Lord,” by Mendelssohn, included a soprano duet. David sang the first soprano and I sang the second. Needless to say, I was thrilled as was my mother, who was sitting in the congregation.

Mr. Reynolds owned a cottage on Lake Champlain in Vermont, to which he invited a few boys for a week each summer. That summer he invited me along with the other boys from our Saturday rehearsals. In May, I had turned 12. David, whose birthday was in the fall, was still 13. At first, my mother was reluctant to let me go, but I begged so much that she finally gave in.

So one Saturday, we loaded Mr. Reynolds’ station wagon with our gear and piled into the car. Of course, we were all wearing T-shirts and shorts. David and I sat next to each other in the front seat while the other three sat in the back seat. There were no seatbelts in those days, and we thought nothing of riding without them. David and I were close enough so that our legs were touching, which I found exciting.

At the cottage we unloaded our gear and went in. In addition to Mr. Reynolds’ room, there were a larger bedroom with three beds and a smaller one with two. Somehow, David and I wound up in the room with two beds.

Of course, the first thing we wanted to do was go swimming, so we quickly changed into our bathing suits and took our towels to the front porch of the cottage. While I still hadn’t really learned to swim, I could keep afloat and dog-paddle. The shore of the lake was rocky and there was no real beach, but there were a couple of flat rocks where we could sit and from which we could step into the water. The water was cold until we had gotten in all over, but soon we were laughing and splashing, ducking each other, and throwing each other about. Mr. Reynolds sat on his porch watching us. We knew he’d come into the water immediately if any of us got into trouble, but of course we never did.

When we had finished swimming and climbed out, we sat on a little bit of grass in front of the cottage and let the sun dry us off. Lunch was sandwiches, cookies, and milk. By the time we had finished all the sandwiches and cookies, we were ready to go back in the water. In those days, however, we were supposed to wait for an hour after we’d eaten before getting in the water, so we lazed about telling jokes and stories. Mr. Reynolds produced a beach ball which we tossed back and forth until finally he said we could go back in the water. We spent most of the rest of the afternoon in the water playing, swimming, and using the beach ball to play a game of modified water polo. We were kids, and we thoroughly enjoyed being kids.

In the evening, supper was hotdogs, tossed salad, potato chips, and milk. Mr. Reynolds had a portable barbecue grill in the cottage which he brought out and set up to cook the hotdogs. When we’d finished them and the coals had died down some, we found sticks and toasted marshmallows. Towards sundown the air began to cool, so we went inside and fetched our T-shirts. There were several boardgames in the cottage, and we played happily until about ten o’clock, when Mr. Reynolds suggested that we should go to bed.

Neither David nor I had brought pajamas, thinking we would just sleep in our underwear. We took our turns in the bathroom, peed, and brushed our teeth before climbing into our sleeping bags. It was still warm in the cottage, so we unzipped our sleeping bags and slept on top of them.

Nobody woke up until about eight o’clock the next morning. Because we had used some muscles the day before which we weren’t used to using, we were all a little stiff, but we quickly loosened up. There was a shower in the cottage, but Mr. Reynolds said that we could bathe in the lake later, so nobody bothered with the shower.

After a breakfast of dry cereal and milk and fruit, we fooled around until it was time for us to get in the lake. We took two bars of soap to share, plunged into the lake, and ducked down so that we were in over our heads. Then we quickly washed ourselves. The question of what we should do about our privates came up, but we decided that since we were in water up to our waists at that point, we could pull our bathing suits down far enough to wash down there too. So, giggling and splashing, that’s what we did. We made little jokes which in those days we thought were very daring.

The rest of the day was much like the first one, with swimming and splashing, eating, and, when we were out of the water, playing board games. Mark Coggeshall and I knew how to play chess and we were quite competitive. After a while the other boys and Mr. Reynolds gathered around us to watch. I was finally able to checkmate Mark and we shook hands when the game was over. The other boys asked us to teach them to play, so during the evening, we showed them the moves of the pieces. There were two sets, so Mark supervised Billy Downing and Brian Masters while David and I played. As we progressed, I showed him a little about how to think through his strategy. Sometimes he would make a move and then see it was a mistake and of course I let them take it back, although I advised him that eventually when he made a move and took his hand off the piece, he wouldn’t be able to change it.

About ten o’clock, we started getting ready for bed. Because it was still warm in the cottage, David and I again opened our sleeping bags to sleep on top of them.

Just as I was falling off to sleep, I heard a little sniffle coming from David’s bed. I listened for a minute, and then I heard more sniffles and some gulps. Getting up from my bed, I walked the few steps over to him. Standing beside his bed, I could hear him quietly crying. I sat on the edge of his bed and put my hand on his shoulder. That startled him and he turned quickly towards me. He tried to hide his tears but in the dim light from our nightlight he wasn’t successful.

“What’s wrong, David?” I asked.

“N…n…n…nothing,” he said.

“Well something’s wrong,” I said. “Are you feeling homesick?”

“No.”

“So,” I asked very gently, “why were you crying?”

I thought for just a moment that he was going to try to deny it, so I reached over and wiped a tear from his cheek. That really got him going! He cried and cried, sobbing and shaking. I told him to move over and when he did, I climbed into his bed with him and hugged him.

Finally, the sobs lessened, and at last he said, “I’m so embarrassed.”

“You don’t need to be,” I said. “It’s just you and me, and we cried together once before. Remember?” He nodded and tried to smile a little at me. “So tell me why you’re crying,” I said.

He was silent for a few seconds before saying, “You wouldn’t understand.”

“Try me.”

Again he was silent before he said, “I’m going to turn 14 this fall.”

“Yeah, so why are you crying about turning 14?”

He gave a deep sigh and said, “Because someday soon my voice will change and then I’ll be out of the choir. I’ve never told you what the choir means to me. It’s the one place where I’m happy. I’m not happy at home, and I’m not happy in school, and I’m certainly not happy in my neighborhood after school. The choir means everything to me, and when I have to leave, I don’t know what I’ll do.”

I sat thinking for a while. How could I answer that? Could I invite him to visit at my house? I asked him that and he said, “No, my dad wouldn’t let me.”

“Well,” I suggested, “we could meet at the quadrangle on Saturdays and go have lunch and spend the afternoon together.”

“When I leave the choir, I won’t have any money to do that. The only reason Mom doesn’t take my choir money from me is because she doesn’t know about it.”

“That doesn’t matter,” I said. “I work at my town library a few days a week so with that money and my choir money we could do whatever we wanted to, and I’d be happy to pay.”

“I can’t ask you to do that,” he said.

“You’re not asking. I’m offering. Look, David, I really like you and I know if I never

see you, then we won’t be able to be friends anymore. Now, move over. It’s getting cool. I’m going to get my sleeping bag and we can use it like a blanket so we can sleep on yours and under mine.

And that’s what we did. I woke up once in the night, and he was spooning me with his arm across my chest and his hard pecker in my butt crack. I began to grow hard myself but thought about other things until I went soft. That was the closest to sex we ever came.

Of course, back then, sex between boys or men was almost never talked about, and at that point I didn’t even know it was possible. The word “gay” in its present meaning wasn’t known. We knew playground taunts like “queer,” and “homo,” but I don’t think any of us at that age really knew what they meant. They were just things we had heard older boys say so we thought they were cool. I learned later that many boys did, in fact, “fool around” together, but I didn’t know it then.

In the morning, I woke first and tried to get up without waking David, but he woke as soon as I moved. He looked confused for a moment as if he didn’t know where he was, but then he smiled and said, “Thanks for last night, and for your offer. I will think about it.”

After peeing, brushing our teeth, and dressing, we went into the living room and played a little chess until it was time for breakfast. It was a cool, overcast morning and not good for swimming, so Mr. Reynolds decided to take us for a ride. After breakfast, we made sandwiches, put on our jackets, and were off.

Mr. Reynolds let me and David follow the map as we went. The cottage was a little south of St. Albans. We took a bridge over to Grand Isle, which is sometimes called Big Hero Island. Stopping at a little town, Mr. Reynolds bought us all sodas. Of course, being boys, we had to see who could make the loudest belch.

Returning to the mainland, we drove south past Burlington to Charlotte, Vermont. There we caught a ferry across Lake Champlain. There was a camp bus on the ferry. The kids were not allowed off the bus, but we were allowed on to chat with them. They were all boys about our age. When they learned we were from a choir, they wanted us to sing something, so we sang part of Purcell’s “Sound the Trumpet.” We left the bus to wild applause.

From the ferry we could see some of the Green Mountains of Vermont as well as some of the Adirondacks of New York. They were pretty impressive to boys who had never really seen mountains before.

From the landing in New York State we drove south to Fort Ticonderoga through picturesque scenery of farms and green fields and woods. At the fort, we took a tour of the battlements. After we ate our lunches, we viewed a demonstration of a muzzle-loading musket and watched people dressed in eighteenth century clothing going about their tasks as they would have in the 1700s. We learned that the star-shaped fort was built by the French to cut off a narrow little river between Lake Champlain and Lake George. It was captured at the beginning of the American Revolution by a small band of Green Mountain boys and their leader, Ethan Allen. Since he was a distant relative of mine, I had learned about the capture and was thrilled to see where it had taken place. The cannons from the fort were hauled all the way to Dorchester Heights, which overlooked Boston Harbor. When the British realized there were cannons pointing down at them, they evacuated Boston.

That night and for the rest of the trip, I slept in David’s bed with him. We cuddled but never went farther, although I know both of us sometimes grew hard.

The next morning, Mr. Reynolds took us on a hike up a mountain. The sun filtering through the trees was hot and we soon had our T-shirts off. When we got to the top, we could see the amazing view through some of the trees. We ate our lunches up there and by the time we returned to the cottage, we were more than ready to swim.

The following day it was pouring rain. We decided to go swimming anyway, but we left our towels in the cottage. After we had been in the water for a while, there was a sudden flash of lightning followed closely by a boom of thunder. You never saw five boys move faster than we did getting out of the lake and onto the covered porch of the cottage, where we stood dripping. A wind came up and we stood shivering as the temperature dropped. Mr. Reynolds fetched our towels so we could dry off before we went inside. We spent the rest of the day playing board games. That night was the coldest we spent there, and David and I cuddled facing each other. We told a few jokes and giggled some but eventually fell asleep and slept until morning.

Our last day was really hot. Mr. Reynolds asked if there was anything special we wanted to do, but we just voted to swim all day. In the evening, it was still hot, so Mr. Reynolds suggested that we go skinny dipping to cool off before bed. I don’t know if any of the other boys had done that before, but I hadn’t, and I thought it was fun and very daring.

At bedtime, David and I enjoyed snuggling again. As we did the previous night, we told some jokes, but then we grew more serious, talking about how much we’d enjoyed the trip and getting to know each other better.

The next day, we were all sad to leave as we bundled into the car for the drive home. I think all of us dozed some on the way.

When we pulled into the quadrangle, my mom was there to meet us. All the other boys had parents there except David. I offered him a ride, but he looked really embarrassed. Mr. Reynolds saw what was happening and stepped in, saying that he was going David’s way and would drop him off. David and I said a shy goodbye and I got into our car. All the way home, I told my mom about the trip. That night I told it all again to Dad. For some reason which I didn’t understand then, I never told them about skinny dipping or sleeping and cuddling with David.

Summer passed, and in late August, I received the usual postcard from Mr. Reynolds. At the first Thursday rehearsal, Mr. Reynolds introduced a few new boys before we got down to business. I was so happy that day, being back where I felt I belonged, next to David and once again being part of that joyous sound.

I wondered if David might say something about what had passed between us at the cottage, but he never did.

The Saturday morning rehearsals continued, and, with the exercises and Mr. Reynold’s coaching, I could effortlessly hit a high C.

After one Saturday session, we were congregated on the quadrangle when David asked if I had ever been to the planetarium show in the natural history museum. I said that I had once, and it was fascinating. “Would you mind going again?” he asked. I quickly agreed and we found that the next show was at two o’clock. That gave us time to go down the street and get some lunch.

We entered the planetarium just before the show began. As the lights dimmed, eventually leaving us in total darkness, we became aware of stars appearing on the ceiling. We watched in awe as a man began to talk and, very slowly, the stars started to move. The man, using a light pointer, showed us various things in the sky – the Big and Little Dippers, Orion, Cassiopeia, etc. At one point, shooting stars flew across the heavens. I felt David take my hand and a little shiver went up my spine. His hand was a little sweaty and I wondered if he was nervous. I responded by gently holding his hand, and we sat that way through the rest of the program. After he took my hand, I don’t think I paid much attention to the last part of the show. When the lights began to come up, our hands automatically separated. We agreed that we both loved that show (“awesome” was not a word that kids used back then) but we never spoke of what happened that afternoon.

After Christmas, we began to work on an anthem which I loved – “Hear my Prayer,” by Mendelssohn. It was an extended work, about seven and a half minutes long. It was the longest piece we sang as an offertory anthem. David, of course, was the soprano soloist, but I also practiced the solos on Saturdays.

On a Sunday just before Lent, we sang it. David was in fine form that morning. His voice seemed to have grown even richer, and I loved the sound.

The piece begins with a long, flowing solo:

Hear my prayer

O God, incline thine ear

Thyself from my petition,

Do not hide.

In time it changes to a call and response between the soloist and the choir:

The enemy shouteth

The enemy shouteth

The godless come fast

The godless come fast

This continues for some time before the soloist finally sings:

Lord hear me call

Lord….

At that point, on a high G, David’s voice cracked, and I mean cracked! Nobody could have missed it. Fortunately, the choir came in for a few bars. As they were singing, David turned to me and said, “Sing, God dammit!”

At the next point where a solo began, I sang:

O for the wings

For the wings of a dove

Far away

Far away would I rove.

This was another long solo, sometimes supported by the choir, until we finally came to the last bars:

In the wilderness build me a nest

And remain there forever at rest.

For a few moments there wasn’t a sound in the building until the organ began modulating into the Doxology. By that time, both David and I were in tears. As we turned to face the altar, I took his hand and just held it while we cried. I know if he could have, he would have fled right then, but there was no way out that wasn’t very open and obvious.

We both managed to hold out until the end of the service and the recessional. When we reached the vestibule, David did flee, not waiting for the final prayer and the amen.

As soon as that was over, I was surrounded by choir members, old and young, congratulating me, while Mr. Reynolds stood in the background beaming.

When we finally returned to the choir room, David’s robe and books were on a chair. David was nowhere in sight.

Even though he had told me that when his voice cracked he was done with the choir, I kept hoping he would return, either on a Thursday or a Saturday, but he never did. In the late spring, one of the choristers who went to school with David, told me that the family had moved. The boy had no idea where. I asked Mr. Reynolds but he didn’t know either. He said he had tried to contact David throughout the spring, even going to his house a couple of times, but he was never able to connect with him. David had simply vanished.

I was promoted to head soloist, a position I had never coveted, and I continued in that role until, about a year later, my voice began to change. Then Billy Downing took over the role. My voice never really cracked, but my lower range began to go down, leaving a gap between that and my higher range. There was a time when I was singing soprano in the choir and baritone in the school chorus at the same time. Eventually, of course, I lost the higher range altogether while my lower range continued down to a low G. I continued in the cathedral choir as a baritone until I graduated from high school and went away to college. Oddly enough, when I was a senior in high school, my range began to go up again and I finally settled in as a tenor. I had been told that no two boys’ voices change in exactly the same way, but I thought my change was quite odd.

********

Slowly, I awoke from my doze. I was surprised to find that there were tears in my eyes. The Allegri “Miserere mei Deus” was playing on my computer. It was the old King’s College Choir recording, with Roy Goodman as the treble soloist.

While I could seldom remember dreams, I did remember that one in great detail.

Finally, I looked again at the picture in my hands. Where were all those boys now? Were any of them still living and singing?

I sighed, rose slowly from my chair, and rehung the picture on the wall before going into the kitchen to prepare dinner.

Many thanks to my beta readers/editors for all their help and suggestions.

~ AD