Boys of Northumbria

by Alan Dwight

alantfraserdwight@gmail.com

“Always keep God’s peace and love among yourselves.”

– St. Cuthbert, reported by Bede in The Life of St. Cuthbert

Preface

In the era known to history as the Dark Ages, Northumbria, in what is now northeast England and southeast Scotland, was ruled by kings. Off the east coast was a tidal island, Lindisfarne, now also known as Holy Island. It was an island when the tide was in but was joined to the mainland at low tide and thus accessible for those who walked or rode horses.

In 635, King Oswald gave Lindisfarne to the Benedictines for the construction of an abbey, which was established under the direction of Bishop Anduin from Iona.

A dispute, mostly over the proper date for Easter but also over the powers of bishops, between adherents of the Roman Rite and those of the Celtic Rite was decided by the Synod of Whitby in 664. Brother Cuthbert as well as many other brothers who had been adherents of the Celtic Rite, accepted the decision.

Cuthbert was soon summoned to Lindisfarne as prior of the Abbey to aid in the transition to the Roman Rite. However, he preferred to live alone and in 676 he was given permission to settle on an island farther east.

In 685, he was recalled to Lindisfarne as bishop, a title which he did not seek but accepted.

Two years later, Cuthbert gave up the bishopric and resumed his life as a hermit on his island, where he died in May of 687. The monks of the abbey transported his remains to Lindisfarne and entombed them there.

Eleven years later, on the day of his translation (in the church, moving holy relics is known as translation) his tomb was opened and his body was found to be whole and undecayed. Pilgrims traveled to Lindisfarne to pray for healing.

On June 8, 793, Vikings raided Lindisfarne, slaying many men and boys and carrying others off to be sold into slavery. Thereafter the monks feared that other raids were imminent.

While they had sometimes gone to the mainland temporarily to avoid the danger, in 875 they departed Lindisfarne permanently, taking with them Cuthbert in his coffin as well as relics of a monk named Bede and other precious items.

Bede had written a biography of St. Cuthbert as well as a history of the area, naming the kings and telling of the monasteries in the region.

The monks wandered in Northumbria for seven years before settling at Conceastre (now Conchester-le-Street) in 882.

In 995, fearing another invasion, the monks moved St. Cuthbert to Durham, where trees were cut and a small wooden church was built as well as cells for the monks.

In 1093, the building of Durham Cathedral was begun on a peninsula surrounded on three sides by the River Wear. The construction was completed in 1133 and St. Cuthbert’s remains were placed in the Chapel of the Nine Altars behind the choir.

In the Dark Ages, each farming family was granted a plot of land large enough to support it for a year. The plot was called a hide. Ten hides made up a tithing; ten tithings made up a hundred, and the hundreds, approximately 10 of them, were organized to form a shire headed by an ealdorman, or after the Norman invasion, an earl. Below the ealdorman were reeves. The term shire-reeve eventually evolved into sheriff.

This story takes place during the moving─or translation─of St. Cuthbert from Lindisfarne to the mainland. The main characters are fictional as are most of the events of the story.

Part 1

Kenric lay moaning on his bed in the ealdorman’s cottage. He was very uncomfortable, having suffered from the bloody flux for several days. He knew that people could die of the flux, and he was afraid, particularly since he had not confessed or been shriven. He suffered from fever, weakness, abdominal pain, and a constant feeling of the need to defecate. A local gatherer of herbs had given him a draught which tasted terrible but did nothing for his cramps and the frequent explosions from his bowels. He ate almost nothing, but he drank great quantities of water.

Each night he feared death before sunrise and lay awake in the near darkness, often trembling from fright.

Death was a constant companion to people living in this, the ninth century. Kenric’s mother had given birth to three boys and two girls. Kenric was the only one to survive more than a year.

When he became aware of the early morning sunlight’s glow, he breathed thanks to his maker for protecting him through the night.

His father, Ricard, ealdorman of the shire, and his mother, Countess Alina, were unable to help him.

Alina had heard of a saint entombed on nearby Lindisfarne who was known to cure illness, and she suggested to Ricard that Kenric should be taken there to pray for a cure. Unable to leave the shire at such a busy time of year, Ricard agreed to send his son to the abbey there with the reeve of the manor, Galfrid, to seek the cure.

The boy was too weak to ride a horse, so Galfrid and his son, Sigfrid, loaded Kenric onto a pallet in a wagon which was pulled by a sturdy farm horse. The three made their way towards the coast. Galfrid drove the wagon while Sigfrid rode in it beside his friend.

Unlike Kenric, Sigfrid had three siblings, an older sister and two younger brothers. Two other siblings, a boy and a girl, had been born dead.

It was August, harvesting time. Sheep were on the hillsides munching grass and muttering to each other. Villeins, or peasants, worked in the fields, cutting wheat and barley with scythes. Usually, Kenric loved that aroma of freshly cut grain, but during his journey he was unable to enjoy it.

The ailing boy had to call a halt more than once on the journey to relieve himself in the woods. The last time, he was nearly too weak to return to the wagon even with Galfrid’s and Sigfrid’s help.

When they arrived at the coast, the tide was in, and it was not possible to cross over to the abbey. Not wishing to attempt a crossing in the dark, they camped nearby. Galfrid and Sigfrid laid Kenric’s pallet near the fire, for it would be a cold night.

Kenric had been born in the autumn and had seen twelve summers. Until he became ill, his life had been carefree. Although his father was the ealdorman, his manor home was simple, with a large communal room of wattle and daub, a central fire, and a hole in the thatched roof to let the smoke escape. There was another, smaller room which his father used for meetings and court.

Ricard taught Kenric the ways of managing the shire and the boy helped with the crops and the care of the animals his father owned. Other than that, Kenric was free to wander as he saw fit, although he was told from early on to stay away from the woods and the road, for it was not unheard of for brigands to wander and kidnap children of lords for ransom.

Kenric and Sigfrid had known each other their entire lives. Sigfrid’s mother, Julia, cooked for Ricard’s family, and Sigfrid’s father, Galfrid, acted as a reeve, tending Ricard’s lands and supervising those who worked on them.

Physically, the two boys were opposites. Kenric was lissome and fair, with a beauty of which he was unaware. Sigfrid was dark and solid; some might even say stocky. Both were strong and hardworking when they were engaged in planting or harvesting.

The boys were together whenever possible. Their favorite pastime was fishing, which they did in a small river flowing through the manor. On hot days, they stripped off their clothes and paddled in the river with the boys of the manor families. That was the closest to bathing that people did in those days.

Julia taught the boys how to clean the fish, cook them, and avoid the bones while eating the flesh.

On the second night of their journey, Kenric lay on his pallet while Galfrid and Sigfrid cooked their food. The sick boy had no interest at all in food, but he was terribly thirsty.

As his companions finished eating and stretched out near the fire to rest, Kenric knew he would be unable to sleep. He could see the sky over the water and wondered, as he often had, what the stars were and how they stayed up in the sky.

The full moon rose, and while it dimmed the stars somewhat, it was a welcome sight to the boy who felt not only weak and frightened but also lonely as he listened to the waves on the shore and to Galfrid snoring and Sigfrid breathing deeply.

Kenric was aware of other sounds in the forest behind him. He heard the scamperings of small animals and occasionally a cry as one was taken and eaten by a predator. The boy knew that there were bears and boars in the woods and he wondered anxiously if some beast would take him as he lay awake and vulnerable.

As the night passed slowly, the air grew cold and Kenric shivered. He had a brychan or rough wool blanket which was pulled up to his chin, but he was unable to stop shivering.

After what seemed like an interminable time, he observed the sky in the east beginning to lighten. He watched as the sun rose, painting the sky with myriad colors.

When the sunlight hit Sigfrid in the face, he groaned, rolled over and sat up. Looking at Kenric and finding him awake, he asked, “How did you sleep?”

“I didn’t,” his friend replied.

“You stayed awake all night?”

Kenric nodded, still shivering.

The boys’ quiet words woke Galfrid, who yawned, stretched, stood, and revived their fire.

The sun rose higher and began giving a little heat which together with the warmth from the fire stilled Kenric’s shivering.

The tide was just beginning to ebb, so they knew they would need to wait until nearly noon to cross to the abbey on Lindisfarne.

Sigfrid sat beside Kenric, who lay quietly near the fire. They said little, but they knew each other’s minds so well that nothing much needed saying. Sigfrid knew Kenric was afraid, and occasionally, when his father wasn’t watching, he held his friend’s hand to comfort him. He wondered if he too might get the flux, but he was young and healthy and optimistic, so he pushed that thought out of his mind.

As they waited, other pilgrims arrived to cross to the island. Several were either ill or in some way crippled, and they hoped the saint would cure them.

When the water had receded and the sun was high overhead, they all made their way across the sand and pebbles to the island. Outside the monastery they were met by a brother of the abbey who was appointed as a hospitaller. He directed them into the building and to the tomb of St. Cuthbert. Galfrid and Sigfrid carried Kenric into the abbey while a novice cared for the horse and wagon.

Lying on his pallet, Kenric waited as others approached the tomb, touching it in prayer. Some wept; some prayed aloud; some prayed silently, their lips moving with their supplications. When at last Galfrid and Sigfrid could move Kenric close enough to the tomb for him to touch it, he laid his hand on the cold marble and prayed silently to the saint for help. Tears coursed down his cheeks. Later he said that while he was praying, he felt the presence of the saint and believed that Cuthbert had reached out and touched him. He said it was then that his fear left him, he wept, and he knew he would be cured.

When he finished, Sigfrid and Galfrid were directed to take Kenric to the hospital, a part of the abbey where he was laid on a bed with clean sheets. Galfrid departed for his supper, but Sigfrid remained beside his friend, holding his hand all through the night.

The brothers in the hospital expected their patients to observe the canonical hours and prayers, prescribed services approximately every three hours. Kenric and Sigfrid were awakened for each service and were taken into the sanctuary for high mass.

Kenric was in and out of sleep throughout the night. When he was awake, he listened to the brothers move about silently tending to their patients. Despite the sounds of people praying frequently, it was a peaceful place, and Kenric felt cared for by the brothers, Sigfrid, and yes St. Cuthbert.

In the morning, he was a little better. He was able to take some broth and a little bread. Later in the day he returned to the tomb and prayed again, this time in thanksgiving for the beginning of his recovery.

Within a few days, he was able to take a few steps and was no longer suffering from diarrhea. Each day he went to the tomb and prayed to the saint. In another week, he felt able to return to his home. His pallet was burned and the hospitallers wished him well.

The return ride was much more joyful than the trip to the abbey. The boys rode in the cart, chatting amiably. It was during this journey that Kenric conceived the idea of becoming a monk and devoting his life to Christ. He thought of learning medicine and the care of the afflicted.

Once, they encountered a traveling party whose leader asked if he was on the right road to Lindisfarne. They assured him that he was. Since the sun was overhead, Galfrid stopped the horse and suggested that they all break bread together. As they ate, Kenric told the members of the traveling party about his illness and his cure.

Arriving home, Kenric was embraced by his mother and Julia. Over the evening meal, to which the family’s priest had been invited, the boy again told of his cure and of others he had witnessed.

“Were all the pilgrims cured?” his father asked.

“Oh, no. Many were not and left the abbey disappointed.”

“Why were some cured and not others?”

“I have no idea,” Kenric replied.

“Perhaps,” said the priest, “their souls were not pure enough. Perhaps they had committed some sin and the saint rejected their pleas.”

Many years earlier, in 788, a nobleman named Sicga, together with others, had murdered King Ælfwald of Northumbria. In 793, Sicga took his own life. Although he was guilty of both regicide and suicide, he had been buried in the abbey’s sanctified cemetery on Lindisfarne.

In June of that year, the abbey had been attacked by Vikings, who destroyed much of the building and slew many of the monks and novices, taking others to sell into slavery. Blood stained the abbey floor and walls, and those who tried to defend the valuable candlesticks, goblets, patens, and manuscripts were brutally slain.

Kenric’s family priest was horrified that such events had taken place, and while he didn’t directly blame the violence on the burial of Sicga, he believed it was blasphemous, and he advised the boy not to return to the abbey.

Nevertheless, Kenric was determined, and he discussed his desire to become a monk with his parents and the priest as well with Sigfrid. Being a monk was looked upon as an honor and a commitment, and many sons of noble families, often the younger sons, took the vows.

Kenric’s mother was saddened by her son’s decision, his father was resigned to it, and Sigfrid tried to talk him out of it.

“Why do you want to do that?” he asked. “You have a wonderful life here and in time you will inherit all your father’s holdings. Don’t you want to marry and have children?”

“I do,” replied Kenric, “yet I cannot forget the miracle which St. Cuthbert gave me, and I feel I want to thank him in the only way I know how.”

Part 2

So it was that when Kenric was 14, he journeyed again to Lindisfarne, this time with his father. Although he was young for a postulant, he wished to wait no longer. This time he was able to enjoy the journey and his surroundings─the budding trees and the blossoming early wildflowers, the aroma of spring in the air, and the sheep cropping grass in the meadows.

Kenric was examined by the abbot of the monastery, accepted as a postulant, and began his training.

Following the first of the three night Vigils, at about 9 P.M., the monks went to bed in the dorter, a long, unheated room on the second floor. Each brother was provided with a bed, a mattress, a brychan, a pillow, and a coverlet. Talking was prohibited.

The monastery kept track of time using a sundial in the daytime and a water clock at night. Both were accurate enough for the monks’ purposes.

For a time, Kenric lay awake, listening to the breathing and snoring of the monks. He missed his bed at home. He missed his parents and Sigfrid. He had just dropped off to sleep when he was awakened for prayers at midnight. Back in bed he fell asleep quickly, but was again awakened three hours later for Lauds, the third of the night Vigils.

At six in the morning the brothers were awakened for the canonical prayers of Prime, the service at the onset of daylight. Following the service there was breakfast with no talking while a brother read from scripture. That was followed by a meeting in the chapter house, and then the men dispersed to their assigned tasks.

One brother was assigned to Kenric and stayed with him throughout the day, teaching him his first lessons in becoming a monk.

Kenric was bright and he enjoyed much of his training. Having learned his letters from his mother, he soon gained the skill of reading. In addition, he was learning Latin. He studied the gospels and the breviary, a book of prayers and readings for the canonical hours. He had a steady hand and a good eye and was soon learning to copy the scriptures.

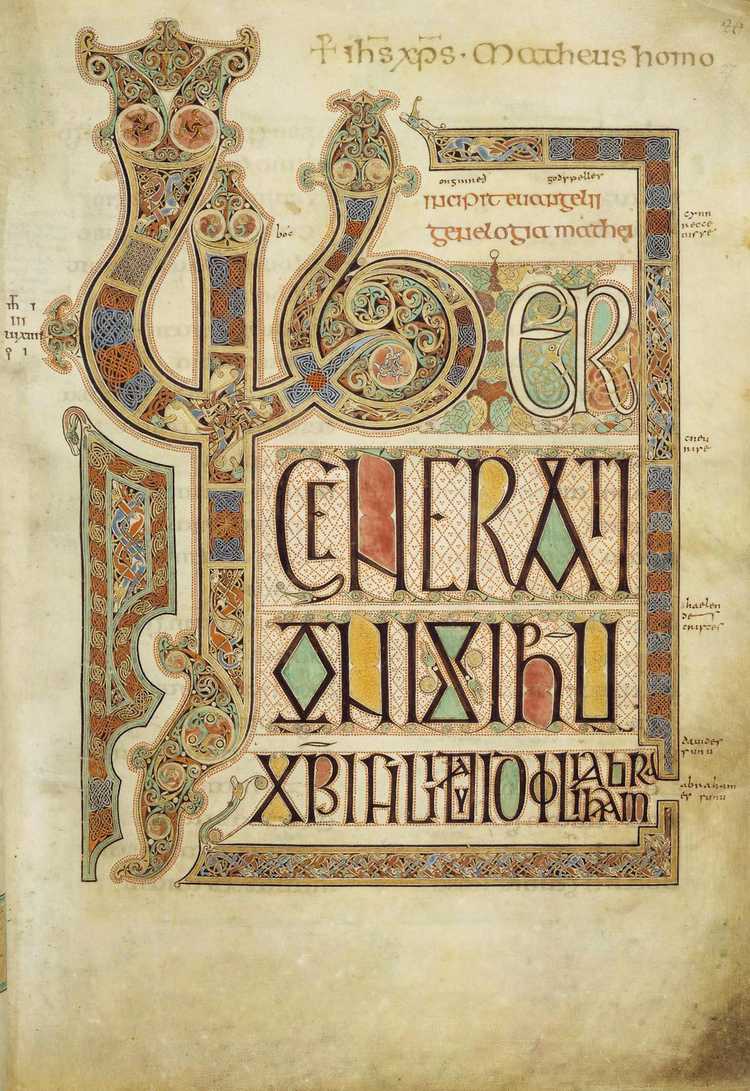

An illuminated or highly decorated and colorful copy of the gospels had recently been created at Lindisfarne (See the title page). The manuscript was shown to Kenric one day by the brother in charge of the scriptorium, and the boy yearned to learn the art of illumination.

One day, as he was copying Bede’s Life of St. Cuthbert in the scriptorium, he found something the saint had said when giving final instructions for his burial:

If necessity forces you to choose one of two evils, I would much rather you dig up the bones from my tomb and carry them away with you and stay with them wherever God sees fit.

Kenric stored this suggestion away, wondering why it would be necessary to move a saint’s tomb.

Postulants were generally advanced to novices after a short time, and remained novices for a least a year, after which they took some simple vows. It was only after more years of training that they took their final solemn vows.

This had all been explained to Kenric, and he looked forward to the day he would take his first vows.

He had a problem, however. Shortly before journeying to Lindisfarne, he had discovered the glories of masturbation. In the monastery it was difficult for him to indulge, for he was seldom alone. Moreover, whenever he succeeded in accomplishing the act, he felt sinful and guilty. At the time, he was unaware that others in the dormitory were similarly active. Although he was attractive, slight, and fair, he was never approached by an older man. He felt he should confess his sins but was afraid that if the abbot and others found out, he would be dismissed.

In some ways, Kenric thrived. While it took him time to learn to pray in the middle of the night, the food was simple but good, although not as good as Julia’s, and he enjoyed the outdoor work in the monastery’s gardens.

Often he appeared happy and productive, but he began to chafe under the discipline of the monastery. Most of the time, talking was prohibited, or at least discouraged. This boy who had known freedom to do as he wished from day to day was suddenly under a strict regimen of lessons and controls. He was expected to be obedient, which was one of the first vows a novice took and followed, the others being poverty and chastity.

He thought about running away, but he believed that he would be caught and returned to the abbey.

Over time he came to realize that he simply wasn’t devout enough to accept a lifetime of monasticism. What he had viewed as his passionate vocation became a burden and a source of sorrow. He missed his parents, and most of all he missed Sigfrid. He continued to feel guilty about his masturbation and particularly about thinking of Sigfrid when he did it.

In time he concluded that monastic life was simply not for him. He went to the brother who was assigned to him and tearfully told him of his decision.

“Why are you crying?” the man asked.

“Because I’m ashamed and discouraged. I thought that becoming a monk would be my way of repaying St. Cuthbert, but I am simply unable to continue.”

The monk said that he understood and that the novitiate was intended as a time of self-examination and reflection. “We recognize that the monastic life is not for everyone, and we don’t attach any shame to decisions such as yours.”

The man communicated Kenric’s decision to the abbot, who approved of the boy’s departure, saying that in many ways the novice had done well and would be missed. He told Kenric that he would send a message to the ealdorman to expect his son home soon.

On the day appointed for his leaving, Kenric thanked the abbot and the monk who had supervised him and departed for home.

Although Kenric would be traveling alone despite the possible dangers of ruffians on the road, the monastery was under no obligation to send someone to accompany him.

He camped at night in the woods just off the road and set off again at first light, accustomed as he was to rise at that time.

The following morning, he encountered three men on horseback. To Kenric they appeared rough, and each carried a weapon, either a dagger or a sword. At first, he was unconcerned. They were not the first people he had met along the way. The men reined in their horses and dismounted. As Kenric tried to pass them, one reached out and grabbed his arm.

“Why are you stopping me?” asked the boy. “I’ve done no harm to you.”

“And none will you do,” the man replied as the other two laughed. “Where are you bound?” he asked.

“To my home,” replied Kenric.

“And where is that?”

Kenric told him, still not suspecting that he was in danger.

“Aha,” said the man, who appeared to be the leader, “a son of an ealdorman. He might be worth a tidy ransom.” With that the other two grabbed the boy and bound his hands behind his back. Then the man hefted the boy up in front of his saddle, remounted, and they rode off.

Kenric was cold and trembling with fear. He was helpless and blamed himself for not being more careful. His father had warned him for years about going about alone, but he had felt very safe in the shire and had never truly considered the dangers of which his father warned.

The men halted for the night, camping in the woods. Kenric was thrown onto the ground and bound to a tree. The three men drank wine with their evening meal, offering nothing to their captive. Drinking quite heavily, they discussed what to do with the boy and how to collect the ransom. Kenric feared for his life but then reasoned that he’d be worth more alive than dead.

In time, the men stretched out, groaned, and slept. Kenric listened to their snoring and to the night sounds around him, trying to figure out how to escape.

When the moon was nearly down, Kenric heard a quiet sound in the woods which he couldn’t identify. It was followed a moment later by “Sssh,” whispered in his ear. He turned his head, and by the fading firelight he saw Sigfrid’s face next to his.

Sigfrid put a finger to his mouth, signaling for silence and very quietly used his dagger to cut the ropes holding Kenric to the tree and the one tied to his wrists. Then he motioned his friend to follow him.

As Kenric began to make his way through the woods, he stepped on a large twig which snapped loudly.

Instantly, his captors’ leader leaped to his feet, brandishing his sword. Sigfrid pushed Kenric aside and charged the man, burying his dagger blade deep in the man’s chest. The man screamed and the other two men awoke. They were groggy with sleep and were easy prey.

Kenric grabbed the leader’s sword and thrust it clean through one of the men while Sigfrid withdrew his weapon from the leader and stabbed the third man.

Kenric looked down at the three dead men with horror. He was shaking. He had never before slain a man. In fact, while of course he had seen dead people, he had never seen a man killed.

“Come,” said Sigfrid, “we need to get away from here.” He gathered the swords and led Kenric to a clearing where he had left his horse with the men’s horses. He brought one of the horses to Kenric and told him to mount, while he mounted his own horse and led the other two. Quietly, they rode out of the woods.

When they were once again on the road to the ealdorman’s cottage, Kenric asked, “How did you find me?”

“I was riding towards the monastery to accompany you home,” Sigfrid replied. “I saw the three men ahead of me also heading towards the abbey, so I slowed and followed them. I watched them take you, but I could do nothing against three armed men, and I knew you were unarmed. I pulled back into the woods and you all passed me as you headed towards your home. I trailed you back to where they camped and waited for them to sleep.”

Because Kenric had eaten nothing since leaving the abbey, they halted in a grassy field, let the horses graze, and shared food that Sigfrid had brought. As they rose to remount, Kenric took Sigfrid in his arms, breathed a quiet, “Thank you,” and kissed his mouth firmly. At first, Sigfrid was startled, but then he responded, returning the kiss, and they held each other for several moments.

Finally breaking the kiss, Sigfrid murmured huskily, “We should go.” Kenric nodded. They gathered the horses and were once again on their way.

Each boy was thinking quietly to himself. While they had been friends for life, they had never shown physical affection other than occasionally hugging or holding hands, and only that when they were alone together. Each knew that the kiss was a new step in their friendship, and each wondered what it meant. Neither had ever heard of men loving men, but they could not deny their own feelings.

They rode in silence for a long time before Kenric said quietly, “What happened in the field, our kiss, must forever remain secret with us.”

Sigfrid nodded. Yet he longed for more. He wanted to hold his friend, to kiss him and to love him. He wondered if he was somehow perverted.

Having grown up on a farm, he and Kenric both knew that in other species, males sometimes mounted other males, and they wondered if men were different. Kenric also wondered if his yearnings were against the will of God. He remembered his need to masturbate at the monastery and his visions of Sigfrid as he did so. Was this natural?

Towards dusk, they arrived at the ealdorman’s cottage. As Kenric dismounted, he was enveloped in his mother’s arms, and he realized that she was crying. His father stood by smiling, while Galfrid and Julia looked on.

Over supper with the four parents, the boys told their tale of kidnapping and escape as the adults listened attentively.

Kenric expressed contrition over the slaying of the three men, but his father told him that he should not feel badly as he had simply done what he had to do. Then he said he would notify the shire reeve of the men’s whereabouts and what had happened.

That night as Kenric lay in bed with no fear of discovery, he brought himself to a powerful climax as he pictured Sigfrid, naked and loving beside him. When he finished, he lay, still with his eyes open, and said a prayer for the souls of the men who had kidnapped him and who now lay dead in the woods.

Part 3

Kenric and Sigfrid quickly settled back into the routines of home. They continued to work on the ealdorman’s land, mostly during sowing and harvesting times. They took part with the men during times of birthing, and when necessary, castrated male pigs, bulls, and sheep, thus controlling the size of their herds and producing fattened animals for food or sale.

On the orders of the ealdorman, the shire reeve had investigated the deaths of the kidnappers. He interviewed the two boys and searched the scene, finding it just as the boys had described it.

Kenric went to his priest to confess the killing, but the priest told him there was nothing to confess.

From time to time they swam or sat on the bank of the river flowing through the property, dangling their feet in the cool water and fishing. One day, as they lay on the bank drying themselves in the sun, Kenric looked about and seeing no one, leaned over and kissed Sigfrid, who responded lustily. Again they agreed that silence was necessary.

After their travels to and from Lindisfarne, the boys wished to explore more of their surroundings, and with the ealdorman’s and Galfrid’s blessing, they began venturing from the manor on horseback, always going armed and never encountering problems. When they had wandered far afield, they ate and stayed in inns which were slowly increasing in number, particularly in the larger towns and growing cities.

Whenever they traveled, they took advantage of being alone to continue exploring their passion. At first they only kissed, but in time they began fondling each other, bringing their friend to exciting climaxes.

The Vikings continued to raid settlements on the east coast of Britain but didn’t return to Lindisfarne.

Once the boys rode to the monastery, for Kenric wanted to visit St. Cuthbert again. He sat beside the saint’s tomb with his hand on the marble and again thanked the saint for his cure.

It was at Lindisfarne that they learned the monks, fearing more devastation from the Vikings, decided that the monastery was too vulnerable and planned to leave it, heading inland away from the danger. Kenric immediately remembered what he had read in Bede’s Life of St. Cuthbert and believed that the saint had been truly prophesying. When Kenric and Sigfrid asked if they could ride with the monks, they were assured that armed protection would be welcomed.

So it was that, when the boys were 16, they rode with their fathers, Ricard and Galfrid, back to the island. There they waited while the brothers prepared the saint’s coffin for transportation, placing it and other valuables on wagons. They took as much with them as they could, including sheets of canvas to protect the saint and their valuables. Although they had no specific destination, they didn’t intend to return.

In 875 they set out for the mainland. Because of the tides, it took more than a day for everyone to cross.

Other armed men, some of them knights sworn to lords, joined the ealdorman and his party as the monks made their way slowly inland, stopping at night to rest themselves and their horses. At all times there appeared to be sufficient men to discourage opportunists from attacking the brothers.

Through the weeks and months that followed, they wandered about Northumbria, traveling as far south as Ripon and north beyond Durham as far as Jarrow, accepting food as alms from generous lords and villeins.

As the men wandered from one place to another for seven years, some left the group of escorts and others joined. The ealdorman and his party returned home from time to time. It wasn’t until 882 that the monks settled at Conceastre, a town north of Durham, where a small wooden church was built along with cells for the brothers. The church was the seat of the Bishop of Lindisfarne, so it became in fact a cathedral. There the saint and monks remained for more than a century as new brothers joined the monastery.

However, after the traveling party arrived at Conceastre, the ealdorman, his manor reeve, Kenric, and Sigfrid returned permanently to their homes. Nevertheless, the boys traveled yearly to Conceastre to pay homage to the saint.

Despite the work on the manor and the fact that there always seemed to be others about, the boys found ways to be alone, sometimes near the stream where they fished, sometimes in a clearing in the woods where they created a resting place.

Alone, they immediately turned to each other, hugged, and kissed. They were aware of their physical arousal and in time began masturbating each other.

One warm day, as they lay in their clearing, talking idly, Sigfrid rolled over, hugged Kenric, and kissed him, first on his mouth, and then on his ears and neck.

Both boys became hard and wrapped their hands around each other’s erections.

“Should we be doing this?” asked Kenric.

“Perhaps you should consult St. Cuthbert,” replied Sigfrid.

“But how would the saint tell us?”

“We’d need to look for some sign of blessing.”

So it was that they decided to consult the saint on their next visit to Conceastre.

On that day, however, their decision in no way prevented them from completing their lovemaking.

As they had no particular duties at the moment, they set out a few days later for the town. On the second day they found themselves confronted by two mounted men with drawn swords.

The boys drew their own swords, then turned back the way they had come, as they had no desire for conflict. They found three more men who had come up behind them.

Turning again to face the first two, Sigfrid began counting very quietly. When he said, “Three,” the boys spurred their horses and charged the men, challenging them. Steel clashed, cries rang out, and the boys were quickly past their adversaries and racing down the road.

Looking back, Kenric saw that they weren’t being pursued. He reined in his horse, calling to Sigfrid to stop. Sigfrid halted and turned, and Kenric saw that his friend’s left arm was bleeding.

“You’re hurt!” he exclaimed.

“It’s just a flesh wound,” Sigfrid replied. “It’s nothing to stop us from going on.”

That evening they camped south of Durham, spreading their brychans on the ground. In the night, Sigfrid began to groan and toss about.

Awakening, Kenric asked, “What’s wrong?”

“Just my arm,” Sigfrid replied. “When we arrive at Conceastre perhaps the brothers can fix it. If not,” he said smiling ruefully, “maybe St. Cutbert can.” He continued to be restless for the remainder of the night.

At first light, the boys arose, mounted their horses, and rode to Conceastre, where they sought out the monks. One hospitaller examined his arm and asked what had happened. When they told him, he said they were lucky to get away, for the five men were outlaws and being hunted by the shire reeve.

He made a poultice and placed it on Sigfrid’s arm, then wrapped the poultice and the arm in some clean linen.

The boys went to the small cathedral to seek out St. Cuthbert. There they found the coffin, covered with an elaborate cloth. Sigfrid placed his hand on the cloth and prayed for healing.

As they exited, they stopped a brother and enquired how the saint would communicate if they asked him a question.

“With your eyes closed,” the man replied, “open a gospel and, place your finger at random on a page. Your finger will point to your answer.”

“I don’t believe my Latin is good enough to translate accurately,” said Kenric.

The man offered to accompany them. They thanked him and returned with him to the cathedral, where they found the gospels on a stand. Shutting his eyes and taking a deep breath, Sigfrid opened a gospel as directed and pointed with his finger on the right-hand page.

“You’re in Matthew,” the monk said. Then he read, translating, “And the second is like unto it. Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself.” Sigfrid looked at Kenric, wondering whether that meant if he loved his body he could also love Kenric’s.”

Kenric understood Sigfrid’s confusion and shook his head. “Let me try,” he said. He too took a deep breath, opened a gospel and pointed.

The brother said, “You’re in Luke. It says, ‘And as ye would that men should do to you, do ye also to them likewise.’”

Puzzled, the boys thanked the monk and departed. When they were down the road a bit, Kenric asked, “What do you think?”

“I think that the saint may be challenging us to think for ourselves. We could take these readings literally and miss his point. St. Cuthbert himself was certainly not involved with physical love of either gender, but he doesn’t seem to be saying that we should not love each other physically.”

Neither of them was satisfied, but they could not think of what to do next, so to pass the time, they wandered about in the small town.

That night they stayed in a small dwelling belonging to the abbey. Again, Sigfrid’s arm hurt him and he was restless.

In the morning they returned to the hospitaller. Sigfrid’s arm was now swollen, but the man applied a new poultice and said that when the swelling had gone down, he would stitch up the wound. “To stitch it before that is to invite an infection which could be fatal.”

They spent a week in Conceastre, and when the swelling at last went down, the hospitaller said he would stitch the wound. Stitching proved to be very painful. Sigfrid was given a piece of thick, hard leather to bite down on. As the stitching progressed, he moaned and tears flowed down his face.

When he finished, the hospitaller said, “You should return to me in three days’ time to let me examine the wound. If you see any redness or pus before that, come back immediately.”

The boys spent the three days strolling in the nearby woods with nothing else to do. They did hear the good news that the five men who had attacked them had been captured and sent to the ealdorman for judgment and, most likely, hanging.

When they returned to him, the hospitaller examined the wound carefully, remarked that Sigfrid would always have a scar on his arm, and instructed him to return in a week to have his stitches removed. He dismissed Sigfrid with the warning to keep the wound clean until it had completely healed.

The following week, the hospitaller was clearly pleased with his work. As he removed the stitches, he said that Sigfrid should have no further problems from the wound.

Brothers at the monastery had cared for the boys’ horses. The two paid for the horses’ food and gave a donation to the cathedral for their care.

The first day of the ride home was uneventful. That night the boys spread their brychans in the woods near the road. When all was quiet, Sigfrid leaned over Kenric and kissed him hard on the lips. Then he kisssed Kenric’s ears and neck. Returning to his friend’s mouth, he caressed Kenric’s lips gently with his tongue. Kenric opened his mouth and Sigfrid’s tongue went in, moving about inside Kenric’s mouth and gently engaging his tongue while his hand sought his friend’s cock.

“Oh,” murmured Kenric, “that’s wonderful.”

When they had both climaxed, they slept soundly.

The second day of their journey went easily. In the evening, the two boys were both ready for kisses, hugs, and tonguing. As they loved each other, they quickly grew hard and once again masturbated each other before sleeping peacefully.

On the third day, they arrived at the manor stables, where they met the ealdorman bearing the sad news that Kenric’s mother, Alina, had died from a sudden fever.

The ealdorman, as well as Galfrid and Julia, had been very concerned when the boys hadn’t returned on time. The two men were about to set out to find them when the young men rode into the stable yard.

Over a subdued supper, Kenric and Sigfrid described their adventure saying that they had truly been very lucky to escape with their lives. Ricard, Galfrid, and Julia agreed.

The next day, there was a service for Alina in the nearby church before she was buried in land set aside as a family cemetery where Kenric’s forebears as well as his siblings were laid.

After waiting for what he thought was a respectful time, two months, Kenric announced that Sigfrid was going to sleep with him in the manor house.

“Is that wise?” asked the reeve.

“Why would you do that?” enquired Julia. ”You should be thinking about marriage, settling down, and providing heirs.”

“I’m not interested in marriage,” answered Kenric. “Yes, I would like children, but not at the expense of my freedom.”

“Are you certain of this?” asked Ricard. “You have an obligation to the family and to the people who will be under you when I die and you inherit the manor.”

“When and if that time comes, I’ll deal with it then. Meanwhile, I will remain with Sigfrid.”

The ealdorman looked at them, nodded slowly, and suggested they sleep in the main room, since he would be in the smaller meeting room.

That night, on pallets spread on the floor, the boys engaged their mouths once more. This time, when they were hard, they pulled up their jerkins and pulled down their trousers. Kenric lay on top of Sigfrid, placing them face to face, and ground himself onto his friend’s cock. They both exploded, their essence wetting their stomachs and chests.

“Oh, yes!” exclaimed Kenric. “How I’ve waited for this moment.”

“Me, too,” agreed Sigfrid.

They cleaned themselves with a piece of old wool, rearranged their clothes, and slept, holding hands.

Part 4

Kenric was certain that his father knew what he and Sigfrid were doing at night, and he was quite sure that Galfrid knew as well. After all, they were both worldly men, and they understood the needs of young men.

They knew that there were daughters of neighboring lords who would be eligible for marriage. For that matter, there were plenty of peasant girls who would be eager for a romp in the hay, but the boys were not interested in the available girls, and their fathers had no stated reservations about the boys’ activities. The ealdorman had no idea what the church would say, but he was not about to consult their priest. Let well enough alone was his motto, and without ever saying anything to each other, Ricard and Galfrid silently agreed.

Winter came, and that year it was a very harsh season. Each night, Kenric and Sigfrid warmed one another as they snuggled in the cold cottage. Peasants died from the cold, as did some sheep and cows, even though some of the animals were taken into the cottages. Fortunately for the ealdorman, the horses survived. Most of the older pigs had been slaughtered for food in the autumn, while the younger ones survived the winter. There was plenty of wood for fires available in the shire’s forests, but deep snow prevented men from venturing far into the woods to gather it. Of those who did, a few didn’t return and weren’t found until after the snow melted. They were buried as soon as the thaw began.

Spring was the usual time for planting. Each villein family planted wheat and barley in their hide. In addition, every cottage had a vegetable garden. There was a large apple orchard available for all the residents of the manor.

Since his mother had died, Kenric took over planting and cultivating the vegetables. He loved the fragrance of the newly dug earth. He found that he greatly enjoyed digging and weeding in the garden and watching the products of his labors emerge from the ground.

During the days, the boys saw less of each other than they had when they were younger, for Sigfrid now had work to do in his own family’s land, but they slept together nearly every night. Occasionally they would still find time to fish in the nearby stream and snuggle on the bank.

The summer was warm and sunny, and people soon forgot the harshness of the past winter. The men and boys worked in the fields, enjoying the sun’s warmth on their bare backs and arms. On the occasional days of rain, they enjoyed the enforced time off from their labors, gathering in groups to impart some gossip and drink barley beer.

The first harvest went well, unhindered by rain. The stalks dried in the fields before they were gathered and winnowed. The resulting grain was stored in wooden granaries raised on rocks to keep out vermin.

One night in autumn there was a violent thunderstorm. The boys lay together watching the display of flashing lightning through window openings, some flashes appearing to strike quite close. After one particularly close strike accompanied immediately by a deafening boom, they heard the chilling cries of, “Fire! Fire!” Hastening out of the house, they saw the cottage of one of the villeins ablaze, flames licking upward from the thatched roof and smoke pouring out of the building. While peasants were gathered around, there was nothing they could do but ensure that sparks from the fire didn’t ignite other buildings.

Lightning also struck in a nearby village, causing a fire that destroyed several homes and took three lives.

In the days that followed, neighbors helped the burned-out family rebuild their home. First they dug holes into which they drove posts. They framed the resulting rectangle with strips of wood which were then sealed with daub, or a mixture of wet earth, clay, and animal dung. Next they thatched the roof. Like the other cottages there was but one room in which the entire family lived and slept.

Through the next winter, Kenric and Sigfrid continued to enjoy one another at night, their passion generating sufficient heat that they didn’t suffer from nights of bitter cold.

Spring arrived, and with it the usual work on the hides. But word soon reached the ealdorman that a small band of outlaws was attacking, robbing, and sometimes killing travelers on the nearby roads.

Daegal, the shire reeve, who was responsible for enforcing the shire’s laws, gathered a group of armed men to patrol the roads in the hopes of capturing the offenders. Kenric and Sigfrid both volunteered.

The roads of the shire were often nearly impassable. While good roads had been built by the Romans in their time, they had not been well maintained once the Romans departed. Bridges were not always safe for men and horses. Many of the roads had become overgrown or sections had washed away.

As the summer wore on, volunteers grew weary of hunting the elusive outlaw band. Daegal often heard that the outlaws had been nearby, but he and his men always seemed to arrive too late to capture them.

Apparently there were four men in the band, and the small group was adept at disappearing into the nearby woodlands.

Then, in early August, Daegal’s luck changed. As he and his men were riding between villages, they suddenly encountered the outlaws, whom Daegal recognized from descriptions he had received from victims. The four were clad in rough wool cloaks with hoods partially hiding their faces.

The four men turned their horses and raced off. Daegal and his men swiftly gave chase. Kenric’s horse was the fastest of the group, but Sigfrid kept close behind him.

As the two young men pulled ahead of the other pursuers, the escaping band suddenly turned with drawn swords and confronted them. There was nothing for it but for the two to draw their own swords and engage in battle.

The bandits knew that if they were captured they would be hanged, so they fought desperately. Kenric slashed down on one of the horse’s hindquarters. The animal screamed and reared, dislodging its rider. This was before the age of chivalry, and Kenric’s goal was to win in any way possible.

When the man fell, one of the other horses shied away, throwing its rider.

The boys were now facing only two, one of whom was quite small and seemed unwilling to fight. This left one man for Kenric and Sigfrid to subdue, and it didn’t take them long.

By then, Daegal and the other men had arrived and were tying up each of the captives.

Kenric turned to the remaining bandit, pointing his sword at his throat. The person cried out in a treble voice, “Please don’t kill me! Please!”

“Throw down your dagger and dismount,” ordered Kendric. By then he was unsure whether they had captured a woman or a boy, but when the person threw back his hood, Kenric and Sigfrid both drew in their breaths.

Standing before them was a boy no more than twelve or thirteen. He had the most beautiful head of golden curls that either of the young men had ever seen.

“What is your name, lad?” asked Kenric, who could see the tears in the boy’s eyes.

“S─S─Seth, sir,” the boy replied, shaking with fear. “Are─are─are you going to hang me?”

“What happens to you will be decided by the ealdorman. Now put your hands behind your back.”

Seth was soon tied up along with the three men and all four were forced to walk towards the ealdorman’s manor while their horses were led by the reeve’s party.

At night the four were tied to trees while Daegal and his men ate and then prepared to sleep. A rotation was set so that there were men on guard duty through the night.

In due time they arrived at the ealdorman’s home. Since it was a warm day, the ealdorman held the trial outdoors. The four were brought before him. He asked Daegal to give evidence.

When he had heard the story, including the tales the witnesses had told the reeve, he asked the men if they had anything to say before he sentenced them.

“Sir,” one of them said, “the boy, Seth, was with us but he never fought or harmed anyone. He is here only because he is my brother, and our parents are dead. I ask you take mercy on him. He doesn’t deserve to hang.”

“But what will become of him if I let him go?” the ealdorman asked. “He is too young to be by himself, and if someone volunteers to take him, how do we know he won’t slit their throat in the middle of the night?”

“Oh, no sir, I wouldn’t do that,” protested Seth, tearfully.

Kenric looked at Sigfrid, who gave a little nod.

“We’ll take him, sir,” he said.

“But then he’d be in my house.”

“No sir, there’s an empty cottage which belonged to Odel before he died. Sigfrid and I can live with the boy there.”

“Well, I’m not sure it’s wise, but if you’re certain. . . “

“Yes, sir, we are.”

“Very well.” Turning to the other three he said, “You shall be hanged within the hour.”

Seth, whose hands had been untied, ran to his brother and hugged him. “Thank you for speaking up for me,” he said. Then turning to Kenric, he asked, “Do I have to watch the hanging?”

“No. Remember your brother as you have known him. You don’t need to see what happens.”

Seth hugged his brother tearfully again.

“Go,” his brother said. “I could not bear to have you witness my hanging.”

Reluctantly, Seth turned to Kenric as the three men were led away to a tree known locally as the hanging tree.

Kenric and Sigfrid took Seth with them to Odel’s former cottage. Thinking to keep the young boy busy, Kenric showed the lad the vegetable garden and taught him how to loosen the soil and pull the weeds. Then he went back to his father to thank him for showing mercy to Seth.

When Kenric returned, he found the boy naked but for a cloth undergarment covering his loins. He’s only a stripling, Kenric thought as he silently watched the boy. Seth’s lithe, strong body was well tanned, and his golden hair glistened in the sunlight. Kenric continued to watch Seth for a few minutes, reminded of what he had heard concerning angels.

“How old are you, Seth?” he asked.

“I’ve seen twelve summers, Sir,” the boy replied.

“You are a good worker,” Kenric said. He gave the boy a few more words of approval and went to find Sigfrid.

That evening, as the three sat around the fire eating, a subdued Seth asked, “Do you think he’s dead yet?”

Sigfrid and Kenric nodded.

“He wasn’t a bad man, really,” said Seth. “He never killed anyone just for the sake of killing, and he took good care of me from the time I was four, after our parents died of the coughing sickness.”

At that, tears ran down his face and he fell into Kenric’s arms.

When he stopped sobbing, he asked, “Where will he be buried?”

“We’ll show you tomorrow,” Kenric replied.

In the night, Kenric and Sigfrid could hear the boy turning restlessly and weeping as he struggled to sleep. When they woke in the morning, he was gone.

“Well,” observed Sigfrid, “he didn’t kill us in our sleep, and if he’s fled, I suppose that’s his affair.” Stepping out of the cottage, he saw Seth in the sheep pasture, picking flowers. He called the boy, who returned to the cottage, clutching a small assortment of wildflowers.

“I want to put these on my brother’s grave,” he said.

After they had broken their fast, Kenric, Sigfrid, and Seth walked to a spot where newly turned earth lay near the hanging tree.

“Is this it?” asked Seth.

Kenric and Sigfrid nodded. Seth moved forward and knelt on the dirt. He closed his eyes and remained for many minutes, his lips moving silently. Then he placed the flowers on the earth before him.

Rising, he observed, “We never went into a church in all the time we were together. I don’t know anything about what comes after dying, and I don’t know anything about praying. Do you think my prayers will help him?”

“Nobody truly knows what comes after death,” replied Kenric, “but I certainly believe that people beyond us are helped by our prayers.” As the three walked back towards the cottage, Kenric told Seth of his faith in St. Cuthbert and how the saint had cured him. Seth continued to be sorrowful for the rest of the day, but in the evening he thanked Kenric for his tale of St. Cuthbert. “Perhaps someday I will go and pray to him,” he observed.

Sigfrid and Kenric looked at each other, a silent message passing between them.

Part 5

One evening as the three sat at their supper, Kenric asked, “Seth, what do you know of your name? Who gave it to you?”

“I don’t know, sir. Probably my mother, although I don’t truly remember her.”

“Were you baptized?”

“What does that mean?”

Kenric explained baptism to the boy, who said he had no idea.

“Do you know who the first Seth was?”

“No, sir.”

“I don’t either,” said Sigfrid.

“Well, Adam and Eve, the first man and the first woman, had three children, Cain, Abel, and Seth, so he’s named in the Hebrew Bible, but I think it’s time for you to have a new name to go with your new life.”

Seth looked at him in wonder. “Can you do that? Can you just change a person’s name?”

“I think if the person is willing, we can. I want to call you Gabriel.”

“Why Gabriel?”

“Gabriel is an archangel, and I think you are beautiful enough to carry that name.”

“I’m beautiful?”

“Yes, you are,” said Sigfrid, smiling, “and I agree it’s a good change.”

“Would you agree to the change?” Kenric asked.

“If you think it’s a good name,” Seth nodded. “It might help me make a new beginning.”

“Fine, I will contact the priest and get Gabriel baptized.”

When they finished eating, they spread brychans on the rushes scattered on the dirt floor and quickly fell asleep.

In the morning, Kenric went to the priest and enquired about baptizing Seth.

“Will you stand for him?” asked the priest.

“Sigfrid and I will, yes.”

It was arranged that the baptism would take place the following Sunday in the nearby village church.

Sunday morning, Kenric and Sigfrid dressed Seth in the finest of the clothes they had outgrown and the three walked to the church. It had snowed in the night. The three had nothing to cover their feet, but with all their work in the fields, their feet were tough, and they barely felt the cold.

When they entered the church, Ricard and Galfrid were already present. Seth looked about the church in awe.

“I’ve never been in one before,” he said. “Is God here?”

“Yes,” replied Kenric, “but God is everywhere, and I feel certain he watches over you no matter where you are.”

“Even when I was with my brother and his friends?”

“Even then.”

During the ceremony, when Seth was asked if he renounced the devil, he looked at Kenric, who nodded.

“Yes. Um. . . I do,” he responded. As the boy Seth had entered the church, at the end of the service the boy Gabriel departed it.

Sigfrid and Kenric, walking behind him, paused at the door for a word with the priest.

“You are right,” the man said, “he does look like an angel. May he have a long and blessed life.”

“Amen,” the young men responded.

In the nights, Kenric and Sigfrid continued their lovemaking. Since they rarely bathed, they enjoyed the strong male scents their bodies gave off. They had discovered oral sex and were sometimes quite loud in their passion. At first they were concerned about what Gabriel might think, but if he noticed, he never mentioned it. On the other hand, he had certainly experienced the glories of masturbation and brought himself to climaxes nearly every night. He was always interested in and envious of the older boys’ sexual equipment and took every available occasion to observe.

Once they began living together, Kenric and Sigfrid had adopted a dog, a large, friendly mongrel whom they named Orvyn. At first the dog needed to learn not to bother them when they were sleeping, but as nights grew colder, he began to snuggle either with them or with Gabriel.

Some nights, when a cold wind was wailing through the chinks in their walls and the fire could not keep them sufficiently warm, Kenric or Sigfrid invited Gabriel to sleep between them. They shared the warmth of their naked bodies. foregoing their sexual activities for the night, while Orvyn lay as close as possible to them. In the morning, they awoke inevitably tumescent. To them, their erections were a natural state and resulted in no embarrassment.

It was again a harsh winter, and sadly for Kenric and Sigfrid, Ricard, Julia, and Galfrid all died that year. The young men’s suppers became gloomy, although Gabriel tried to cheer them up. Kenric was appointed ealdorman by King Alfred, and Sigfrid became Kenric’s manor reeve. Kenric, Sigfrid, and Gabriel all moved into Ricard’s old cottage, giving the building they had occupied to a young couple.

In the warmth that spring brought, they plowed their land and did their planting. Gabriel had never planted anything before, and he was soon rewarded by new shoots pushing up out of the earth in the vegetable garden. He tended the plants, which he soon considered his, with great care, anticipating the time when he could harvest beans and melons, onions, and potatoes. When the days were warm enough, they returned to the river, joining the younger boys from the nearby hides and splashing about.

As summer approached, Kenric and Sigfrid began to think about a pilgrimage to St. Cuthbert, which had become an annual tradition for them. They asked Daegal to supervise their lands and rode off towards Conceastre with Gabriel, who was making his first pilgrimage. Orvyn always enjoyed an outing. The dog spent much of his time snuffling in the woods, exploring the scents, and occasionally killing and devouring a small animal.

Arriving in the village, they made their way to the abbey. They left Orvyn with the horses while they entered the abbey and knelt by St. Cuthbert’s tomb, praying for family members they had lost.

Outside the abbey, the young men met their friend the hospitaller and introduced him to Gabriel. The brother offered to show the boy around, so Kenric and Sigfrid left to walk in the town, knowing that their young charge was in good hands.

Later, as Gabriel talked about what he had seen, it was clear that he had been very impressed. He told about visiting the hospital and talking with some of the patients. More than a few thought at first that he was an angel, come to carry them off, but he assured them he was only a boy who had come to visit the saint’s tomb.

Several days later, as the three rode off towards home, Orvyn sniffing about nearby, Gabriel kept up a constant stream of conversation, telling about all his impressions of the abbey and the brothers. He had met the abbot, observed the brothers in the scriptorium, attended services, and marveled at the abbey’s gardens.

“I need to learn to read,” he said at one point. “Will you teach me?” Kenric assured him that he would.

Nearing the end of their journey, Gabriel asked Kenric to tell him what it had been like to be a novice in the abbey. Of course, the abbey’s location had changed and there were no stone buildings, but Kenric knew the lives of the brothers hadn’t changed very much, and he told in some detail what life was like for them.

“Do they do things in the night like you and Sigfrid do?” he enquired.

“No. It’s not allowed,” Kenric replied.

Gabriel grew silent and thoughtful. Sigfrid looked at Kenric, and one of their silent messages passed between them.

At home, Kenric began to teach Gabriel to read. The boy learned his letters quickly and was soon sounding out words. Ricard had owned a Saxon version of the Gospel of Luke, and by Christmas, Gabriel was devouring it. He learned for the first time the Christmas story of the birth of Jesus.

“Was Gabriel one of the angels who appeared to the shepherds?” he asked.

“The gospels do not tell us the names of the angels, but it was an important event and I imagine the archangels were present,” replied Kenric.

As usual in winter now, their sleeping arrangements called for the three occupants of the ealdorman’s cottage to snuggle together for warmth, joined of course by Orvyn and other animals. Kenric and Sigfrid never touched Gabriel sexually, and the boy never approached them to share his body.

It was only as spring began to arrive that Gabriel told the others his thoughts about becoming a monk.

“You know,” he said, “I have never really belonged anywhere. You have given me the closest thing to a home I have ever had, but I am attracted to the lives of the brothers, and I believe a life of good works and contemplation would suit me well.”

“Before you commit yourself,” cautioned Kenric, “think carefully about what you would be giving up. Perhaps you have not known us long enough to miss us as I missed my family, but I also felt confined and, by the way, unable to share my body with another boy as I wanted. It took me time to understand that God created sex. I believe he approves of my union with Sigfrid.”

“Being confined is also being secure,” said Sigfrid thoughtfully. “Perhaps that’s part of what Gabriel is seeking.”

“Yes,” the boy responded. “As for having a relationship like yours, I do not believe it means as much to me as it does to you. I’m willing to forego that.”

The discussion continued for several days. Kenric certainly did not try to talk Gabriel out of his decision but wanted to be sure that he entered the abbey with his eyes open and his mind thoroughly committed.

Seeing that Gabriel was determined to join the monastery, the three returned to Conceastre that summer and sought out the abbot. Gabriel and the abbot had several lengthy discussions, and the boy was in time accepted as a postulant.

So, three had journeyed to the abbey and two returned to their cottage. Kenric and Sigfrid planned to continue their yearly pilgrimages to St. Cuthbert and knew they would visit Gabriel each time.

In the monastery Gabriel felt as though he had finally found what he was seeking ─ peace and fulfillment. True, the first few days and nights were difficult. He was unaccustomed to waking for prayers in the middle of the night and to sleeping alone but in a dormitory with the other monks.

He knew he would never have the kind of relationship that Kenric and Sigfrid had, yet he felt very close to God and to St. Cuthbert. True, it was not a sexual closeness, but it was to him a loving one.

In his first days at the abbey, he was given a tour by Baldhelm, a novice three years his senior. He saw where the herbs were cultivated for the hospitallers, where the parchment was prepared and the manuscripts were copied and where the food for the abbey was grown. A part of every day was given to learning─to reading, Latin, writing, and arithmetic. Nearly all his reading was in the gospels, although in time he read other portions of the holy scriptures, including the creation story and the commandments. The only time he had for daydreaming was when he was working in the fields and orchards.

Gabriel’s period as a postulant was brief, and he quickly became a novice. He worked at memorizing the psalms, readings, and prayers found in his breviary, or service book. He was soon able to recite them with no reference to his breviary.

He was a hard worker. His efforts and abilities were quickly noted by the brothers who taught him, and they passed on their information to the abbot.

When he completed training as a novice, he took the Benedictine vows of Obedience, Poverty, and Chastity and settled into the lifetime commitment of a monk.

In time, Gabriel became a scribe, carrying on the tradition of the Lindisfarne Gospels.

The only issue he had was with brother Baldhelm, who grew jealous of the younger monk. Gabriel was given tasks and duties which never fell to Baldhelm, who eventually raised the issue with the abbot.

“Baldhelm,” the abbot said, “we give to each brother the tasks which we believe he will best accomplish.”

“Are you saying that Gabriel has abilities which I don’t have?”

“Of course. We each have our own abilities. Comparisons are not productive.”

“But I want to copy texts also.”

“Then you need to practice. Perhaps you will in time become sufficiently able to do so successfully.”

When Baldhelm departed he was angry, believing he was fully capable of being a scribe, but although he worked hard to develop his skill, he never truly succeeded.

Gabriel was aware that for some reason Baldhelm resented him, but he decided that the older monk’s resentment was simply the way of the world, and he went on with his work, ignoring the man.

Kenric and Sigfrid grew older, as people do. They managed their lands and the shire’s affairs. When Kenric was called on to judge men, he was always fair according to the laws of his time. As the king’s laws specified, Kenric collected the taxes in the shire and also as specified, kept a third of them for himself, turning the rest over to the king.

Orvyn too grew older. He found it more difficult to travel far. One day he took himself into the woods. Instinctively, he knew he was dying. He lay down, gave a deep sigh, and passed on.

The two men adopted other dogs, training each of them how to act as they traveled and slept together.

Sigfrid died in his 57th year and Kenric mourned him. That summer, he rode to the abbey alone. He met Gabriel, who had become sub-abbot, and told him of Sigfrid’s passing.

“I shall pray for him,” replied Gabriel. “But then, I have always prayed for you both.” They embraced and Kenric rode off home.

Often, like St. Cuthbert, Gabriel went out to villages preaching his faith and the word of God. As was the custom in those days, when a priest or monk arrived in a village to preach, word spread quickly and people from miles around ventured to hear him.

One day a young man who suffered frequent seizures was brought to him. Gabriel asked for a cup of water, blessed it, and told the young man to drink. That night the boy fell into a deep sleep. When he awoke in the morning, he was cured and never had another seizure.

Gabriel’s reputation as a miracle worker began to grow. When he was sought out, he prayed to cure whatever ailment was brought to him. Some people were cured; many were not. The monastery prior told him that the cure would depend on whether or not the supplicant truly believed that he would be cured.

Without his life partner, Kenric grew sad but knew that Sigfrid would want him to continue to prosper. Perhaps Gabriel’s prayers helped, for Kenric lived another 13 years, dying one warm summer day with his dog by his side. He had few expenses in his later days, and he left all he had as a donation to the abbey.

When Kenric did not arrive at the abbey that summer, Gabriel knew he had lost his friend and protector. With the abbot’s permission, he rode to the familiar cottage, found where Kenric and Sigfrid were buried, and remained by their graves for a fortnight of contemplation and prayer before returning to the abbey.

As he aged, Gabriel looked forward to the time when he would join his Lord and all the believers who had passed away. He continued to read about St. Cuthbert’s life, the miracles he worked, and his belief that he would be welcomed into heaven.

One day as Gabriel was walking with a novice to a village far from the monastery, he suddenly put his hand to his chest, said, “Oh,” and collapsed. The novice sent for the nearest priest, who arrived in time to administer the last rites to the dying man.

Gabriel died with a smile on his lined and weathered face, knowing he would soon be joining his brother, Kenric, Sigfrid, and all the other saints of heaven.

Many, many thanks to my editors without whom this story would have been nearly unreadable.

Also thanks to Mike for maintaining this wonderful website. Please consider making a donation to continue the site.

Image credit: Folio 27r from the Lindisfarne Gospels, incipit to the Gospel of Matthew. The main text contains the first sentence of the Gospel According to Saint Matthew: “Liber generationis Iesu Christi filii David filii Abraham” (“The book of the generation of Jesus Christ, the son of David, the son of Abraham”). See Lindisfarne Gospels for more information.