A Wash Ashore

Chapter 5

Provincetown Harbor with the Mackerel Fleet Heading Out

Josiah and I worked together all through the summer. We were never paid a lot, but it was enough to cover our rent and food. To save money, we washed our clothes in the kitchen when it wasn’t being used by Mrs.Trumble. There were clotheslines outside where our clothes could dry.

From time to time, we continued to look for work in the stores, but found nothing until one day in September, I found a job which had been vacated by summer help. I worked in a chandlery while Josiah returned to school in Provincetown. Our income dropped of course, but I was making a little more, so we were able to scrape by.

Chandleries were stores which sold all sorts of equipment for ships and boats, including ropes, tar, hammers, nails, caulking, pulleys, fishing nets, even dried food for the schooners which sailed to the Grand Banks. I likened them to hardware stores for ships.

As we were talking with Mac Trumble one day in early October, he told us that there was a man in town looking for us.

Josiah and I looked at each other and exclaimed in unison, “Father!”

Mac said he hadn’t told the man where we were but had said that, if he met us, he’d tell us about him. When Mac asked, the man had told him he was staying at a local inn.

After discussing what to do, Josiah and I decided that we had to meet him eventually, so we shouldn’t put it off.

The next evening, after I had cleaned myself and changed clothes, we went to the inn and asked for Jacob Tyler. We were referred to room 7, which was on the second floor. We climbed the stairs and walked down a corridor until we found the room. I knocked.

The door opened and there was Father, standing tall as always. It was difficult to tell from his expression what he was thinking.

“Come in, boys,” he said.

We stepped into the room, and he motioned for us to sit on a small settee, while he sat in the only chair.

“Well,” he began, “you boys gave me quite a runaround.”

When we didn’t respond he went on, “Your mother and I were very upset when you left, and Edwin was inconsolable.”

“I’m sorry,” I said quietly.

“I first thought you might have gone to Chatham, so I traveled there and asked around for you, but nobody had seen you. Then I began to wonder, if I were running away from home, where would I go? In the middle of the night I thought, ‘Provincetown’. This is my third trip here. I found a few people who said they had seen you around, but either they couldn’t or wouldn’t tell me where you were. Of course, if I had spoken Portuguese it might have helped. Who told you I was here?”

“The man whose house we’re staying in,” answered Josiah.

“Mr. Trumble?”

“Yes, sir,” he replied.

“I wondered if he might actually know where you were when he asked me where I was staying. So, here we are.”

“Are you angry with us?” asked Josiah quietly.

Father thought a minute before saying, “No. I was angry at first, partly because you had defied me and partly because you hurt all of us, especially Edwin. But as time passed, so did my anger. I think I understand now why you did it, and in fact I realized I had inadvertently planted the idea in your heads. So, tell me about yourselves.”

Between the two of us, we told him about our journey to the town, finding a room to rent, and getting jobs. We talked about working at the fish pier and then my getting a new job while Josiah returned to school.

When we finished, Father said, “It sounds as though you were both resourceful and fortunate.”

“Yes, sir,” I said.

“There is the issue that I am still Josiah’s guardian as well as your parent. I don’t know just what the law has to say about that. At least for now I won’t do anything about it, but since you’ve been away for a while, do you think you might be able to return home?”

“No, sir,” we both answered.

“Not under the same terms we were living under before,” I said. “We’re doing fine and we’re happy. Of course, we both miss the family, and maybe someday we’ll travel home for a visit, but we both want to stay here.”

Father nodded and said, “I suppose I’m not surprised. Are you continuing your depraved behavior?”

We both nodded, and then Josiah added, “But, sir, we don’t consider it depraved. We simply love each other.”

“Do people here know about that?”

“Well,” I answered, “the bedsprings do make quite a racket, so the Trumbles may know, but if they do, they haven’t said anything. They’ve been nothing but kind to us.”

Nodding he changed the subject, and to our surprise, asked, “Have you two had dinner yet?” When he learned that we hadn’t, he took us to a very nice restaurant, much nicer than we could afford ourselves.

We talked back and forth over dinner. When I asked after Edwin, Father said that he thought he was still a little sad but otherwise he was fine.

“Tell him I’m sorry he was upset, and I think of him often, as I do you and Mother. Perhaps we can visit sometime over the winter.”

Father suggested we might want to visit over Christmas, and we said we’d try. We also said that we’d try to write frequently.

With dinner over, we walked with Father back to the inn. Standing at the door, he hugged us both. He said that he loved us despite his disapproval of what we were doing. He added that he was glad we were doing well. With that, he went inside, and we returned, well-fed, to our room.

Over a simple Thanksgiving dinner a few weeks later, we discussed going home for Christmas. Josiah had been to the railroad station and found out what the trip would cost us. We had saved nearly enough money and thought we could save the rest before the holiday, so we resolved to go.

++++++++

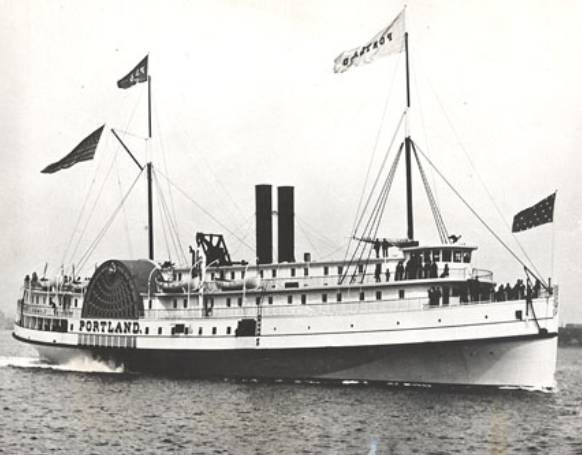

The Portland

On the Saturday after Thanksgiving, the skies turned an odd shade of yellow, what Cape natives called ‘greasy skies’, but the day was calm until the evening, when the winds began to increase. As we lay in bed that night, having enjoyed our usual exploits, we listened to the winds, which had begun to scream, and I thought once more of banshees. It took us a long time to go to sleep.

In the morning, we were awakened early by the storm which was continuing unabated. We looked out on an eerie scene. Two ships, the Jordan L. Mott and the Lester A. Lewis, had sunk in the harbor. Both had men clinging to the rigging. From where we were, we were unable to determine whether they were dead or alive.

During the day, men from the Land’s End life-saving station out on the coast were miraculously able to drag their surfboat and equipment through deep snowdrifts and across a tidal inlet to the town.

Climbing the rigging, the rescuers cut men from the Mott’s lines. Captain Dyer and the ship’s boy barely survived. The captain’s father and the steward perished.

There were four frozen men in the rigging of the Lewis. Since they were clearly all dead, they weren’t cut down until the next day, when it was safer to do so after the wind had died down to a gentle gale.

Braving the wind, Josiah and I walked to the wharves. Although the harbor was well protected by land, in all, some twenty vessels were either sunk or washed ashore. Derelict wharves which had not been maintained had been washed away, their debris and that from buildings on the harbor having been blown to the western side of the harbor.

In the following days, we learned more about the devastation. Since telegraph lines had been blown down along the Cape, we were temporarily isolated. We learned that train tracks had also been washed away in one place, so our thoughts of going home for Christmas were dashed.

Talk began to circulate around town that a large, side-paddlewheel boat, The Portland, had been lost at sea. If that was so, all the passengers and crew were lost. Later we heard that a few bodies and wreckage had been washed up on the Outer Cape. Oddly enough, many of the bodies wore wristwatches which had stopped at 9:15, but nobody knew whether that was AM or PM. In all, nearly 200 souls on the ship were lost, and the gale became known as ‘The Portland Gale’.

In Provincetown, people at once began to clear away the wreckage and help homeowners whose houses were damaged. It was a tedious process. The lost wharves were never replaced as fishing in the town had been a dying economy for some time. Fishing boats carrying ice and returning from the Grand Banks could head directly to Boston to unload their cod and other fish.

When at last communication resumed between Provincetown and the rest of the Cape, we wrote to our parents, telling them that we wouldn’t be able to get home for Christmas that year, but that barring further disasters, we hoped to get home the following December.

With many of the wharves gone and much of the fishing gone, businesses like the chandlery where I worked closed down, and I was out of a job, as were many others who lived year-round in the town.

People had begun to talk about a new venture ─ building the town’s economy through tourism. With the advent of the train from Boston to Provincetown, tourists had started to venture to the end of Cape Cod. Inns and rooming houses had multiplied. Of course, much of the tourism was in the summer, but there were tourists who came in the fall and the spring and even in the winter.

Some of those who began arriving in the summer were artists from New York City. They came for the daylight unspoiled by the dirt and grime of the city. They began to teach classes to summer tourists, many of the visitors being young ladies.

I was at last able to find a job working in one of the new inns. I took reservations and superved the desk and the other employees ─ mostly cleaning and maintenance people. I soon became indispensable to the owners, who were also running another inn.

++++++++

In the summer, Josiah got a temporary job working in the other Inn my bosses owned. He began talking from time to time with one of the artists from New York, who was living in the same inn. The man’s name was Morris. When Josiah learned that he was queer, the two grew quite close and spent a great deal of time together. I had no interest in Morris. After all, I had Josiah, or so I thought, but I began to wonder about our relationship. Was I losing him?

One night, Josiah didn’t return home. When he wasn’t there by supper time, I ate alone; when he didn’t return by bedtime, I slept alone. By then I was highly concerned. Not only did I worry about losing him, I worried about whether he was safe or lying injured somewhere.

In the morning, before I left for work, he returned. He looked at me and I looked at him. “What happened?” I asked.

“I don’t want to talk about it,” he said.

“Don’t you think I deserve to know?”

“Maybe later.”

I had to be satisfied with that. All day I worked, worrying about Josiah. One of the employees mentioned that I seemed to be lacking concentration and asked if I was okay. I assured him I was, although I knew I wasn’t.

When I returned to our room after work, Josiah wasn’t there. Again, I ate alone and went to bed alone. That went on for three nights. Each morning he returned but wouldn’t say where he had been.

In the middle of the fourth night, I heard steps on the stairs and Josiah entered very quietly.

He undressed silently and crawled into bed beside me. We lay side by side without speaking, but I could tell he was crying.

I rolled over and hugged him. He clung to me as though he was almost desperate, great sobs coming from him.

When at last his crying slowed, he reached over and still hugging, he kissed me hard on the lips.

He lay back and began to speak, so quietly that I could barely make out what he was saying.

“I’m so, so sorry, Caleb.”

“Can you tell me what happened?”

“I spent my nights with Morris.”

I asked fearfully, “Were you having sex?”

I felt him nod.

“Do you want the two of us to separate?”

“No,” he answered, “but I’m really confused. I love you, but Morris fascinates me, and he’s taught me things. I don’t know what to do.”

After thinking, I said, “Josiah, I don’t truly understand, but what I do know is that I can’t go on like this. Either we’re together or we’re not.”

“I know,” he said through further tears. “Can you give me a few days to figure it out?”

“I suppose so, but only a few. I need to know where I stand with you.”

“Certainly you do,” he said. “Can I stay here for the rest of the night?”

I assured him that he could.

In the morning we ate breakfast silently. Before I left, we kissed, but it wasn’t the kind of kiss I was accustomed to. I sighed and went to work.

There were other nights when Josiah wasn’t home. I knew he was trying to figure out what to do and say, but I grew impatient, and finally one morning when he was home I told him we had to talk.