A Wash Ashore

Chapter 2

A Cape Cod Lifesaving Station

I watched the room grow slowly lighter and soon there was sunlight flowing through the window. Mother called us to get up and go down to breakfast.

“I’m not hungry,” Josiah said, turning towards the wall.

“Well, you have to eat anyway. You haven’t eaten a thing since you got here. C’mon, get up.” I took hold of an arm and a leg and pulled him out of the bed. He just flopped on the floor and curled up in a tight little ball, like Mother’s balls of yarn she used when she knitted.

“Leave me alone,” Josiah said.

“No,” I said, sitting down beside him. “You have to get moving. Lying on the floor’s not going accomplish anything.”

I stood, put my hands under his shoulders, and picked him up.

He was limp at first but then he stood, just looking at me, and asked, “What should I wear?”

“We usually wear our nightgowns and robes to breakfast. Let’s go down.” Josiah followed me down to the kitchen table, where Mother had laid out oatmeal and toast.

As we sat, Mother was busy kneading dough for the day’s bread, while Father added more wood to the stove.

My younger brother, Edwin, who had slept through the night’s tragedy, looked at Josiah and asked, “Are you Josiah?”

“He’s Josiah Parker,” I said, “and right now he doesn’t feel much like talking.”

“Oh,” said Edwin, and he turned back to his bowl.

We sat at the table with Edwin and my parents. We linked hands, all except Josiah, who didn’t understand what we were doing. I reached over and took his hand while mother took his other one. Then Father said a blessing.

Breakfast that morning was a quiet meal. Nobody except Edwin felt like talking and he soon picked up on the mood.

When we finished eating, we took our dishes to the sink. It was Edwin’s and my job to wash and dry them and put them away.

While we worked, Father smoked his pipe and looked at a two-day-old newspaper.

As we stood at the sink, Edwin whispered, “Is he okay?”

“He will be. I can’t talk about it right now.”

Mother produced some of my old clothes which she thought might fit Josiah. She never threw any of my clothes away, and poor Edwin inherited all of them. I don’t think he ever got any new ones.

When the dishes were washed and put away, Josiah and I went back up to my room, where I handed him the clothes.

Looking at me, he said very quietly, “Thank you. I couldn’t answer Edwin.”

“I know,” I said. “It’s hard to deal with his curiosity sometimes.”

“How old is he?”

“Eight, going on forty,” I replied. “He’ll be fine. Mother will explain to him what happened. You don’t have to say anything.”

Josiah nodded and began to put on the clothes. When we finished dressing, we went back downstairs and outside.

I stood, inhaling the delicious, fresh, salty air of the sea. Without saying anything, we went past our shed and onto the beach. Turning north, we walked slowly and silently along the sand.

After a time, I asked, “Did you say you had no relatives?”

“Not quite. I said I had nobody to live with. My grandmother, Mother’s mother, is alive but just barely. She has to have someone stay with her all the time and I guess Father thought that was a job I shouldn’t do. Anyway, I don’t know where I can go now. I suppose that’s another reason I’m sorry I was rescued. Any one of those men would have been of more use than me.”

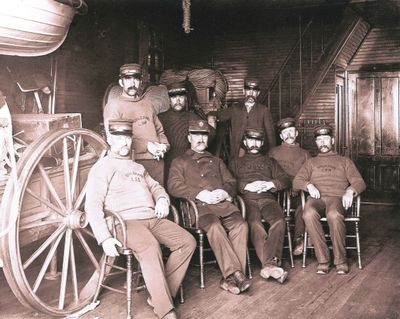

A Lifesaving Crew

I put an arm around his shoulder. “That’s not true, Josiah. You can accomplish a lot as you grow up. We walked, silently. Eventually we came to the lifesaving station. There were lifesaving stations all along the coast, spaced out about every four or five miles.

“I think I should go in and thank the men,” Josiah said.

“Is that a good idea? You’re not going to tell them you wish they hadn’t saved you are you?”

“No, he answered. “I’m just going to thank them for trying to save the others.”

Inside the station, the men were at their regular morning chores. They looked up as we drew near and then went back to work.

“Josiah has something he wants to say,” I announced.

The men turned and looked at us. I could see they were upset at not having had much success in rescuing the crew.

“I just want to thank you for what you did the other night,” Josiah said. “Of course, I wish that everyone could have been saved, but I know you tried hard and went into danger. So, thank you.”

Josiah turned and walked out of the building. I followed behind, but he was walking quickly, and it took me some time to catch up to him.

“That took a lot of courage,” I said. “I’m sure the men appreciated it.”

He turned his tearful face towards me and nodded. As we walked back along the beach, he took my hand. I wondered if it was a younger boy seeking support or something else I couldn’t fathom.

That night as we prepared for bed, Josiah stood looking out the window. When he spoke, it was as though he was talking to himself.

“What would happen if I just walked out into the sea and never came back? Then the pain would be gone, and I could be with Father and Mother.”

Turning to me, he asked, “Do you believe in God?”

It had never occurred to me not to, and I assured him that I did.

“If God was there, why didn’t He save everyone? Why did they have to die?”

I thought about his question for a minute before I said, “I don’t know. I guess we can’t understand why God does what He does. That doesn’t mean that He’s not there or not caring.”

“Well, if he’s there, I’m really angry at Him.” He sighed and we climbed into bed.

++++++++

Over the next few days, Josiah seldom spoke. He wasn’t rude; he was just silent.

The day after we went to the lifesaving station it poured rain, only abating in the evening. Edwin and I both grew restless, for there was little to do indoors except read or play games like checkers or cribbage. Edwin and I spent large parts of the day playing the games, but Josiah simply sat and watched or went upstairs and stared out the window, watching the waves pound the shore.

In the mid-afternoon, he came downstairs and said, “Someone’s been washed up on the beach. I’m going to look.”

Believing it wasn’t good for him to go alone, I hastily gave him a slicker, put on mine, and we went outside. The wind was blowing hard from the northeast and the rain was slashing into our faces.

We reached the body on the beach. It was lying face down. Some of its clothes had been torn off by the sea. Josiah and I turned him over. The man’s face was partly destroyed by the action of the waves and the sand as he floated in.

Josiah gave a little gasp. “That’s Father!” he exclaimed, tears streaming down his cheeks.

“Poor man,” I said, as I put my arms around Josiah. “I hope he didn’t suffer too much.”

We pulled his father up on the beach where he wouldn’t be washed out to sea again, before we walked to the lifesaving station to report our find. Some of the men returned with us and, placing the man on a stretcher, began to carry him back to the station.

“What will happen to him?” Josiah asked as we walked along beside the stretcher.

One of the men answered, “We’ll clean him up as much as we can and then he’ll be buried up in the graveyard, beside the other sailor who drowned.”

“Can you let me know when that’s going to happen?”

“Of course,” replied the man, “we’ll send someone for you.”

We returned home and got out of our soaking clothes. Then Josiah returned to his post at the window, perhaps hoping to see other men washed ashore.

The sun was shining the next morning when there came a knock at the door. Mother answered it and, returning, told us that the burial was about to happen.

Father didn’t open his store that day. My family and Josiah trudged up the hill to pay our final respects. The minister said a few prayers, and the body was lowered into the ground. I saw Josiah crying silently. He didn’t deserve this, I thought.

++++++++

In the middle of the night, I awoke and discovered that Josiah wasn’t in my bed. Looking out the window, I saw him standing on the beach right at the water line.

I raced downstairs, shouting, “Father! Help!” as I ran. I slammed open the door and tore across the beach.

At first, I couldn’t see Josiah, although the moon was just a little past full. Then I spotted him. He was standing out in the water with only his head above the surface.

“No, Josiah!” I yelled. He turned to look at me for a moment and then he disappeared.

I ran into the water and as soon as it was deep enough, I began to swim towards where I’d last seen him. I found him by pure chance as my head bumped into him. I wrapped one hand under his arm and around his chest and began trying to swim back to the beach, but the tide was going out and I felt I was making no progress at all.

What should I do? I wondered, desperately. Should I let go of him and save myself or should I risk drowning with him?

I couldn’t just abandon him, so I held on as tightly as I could. It seemed that a great amount of time passed as I struggled with him before I suddenly felt strong arms grab me.

“Hang onto him!” Father shouted over the sound of the waves. He began to walk us back to the beach.

On the shore, I stood but Josiah lay still, sprawled in the sand. He was pale in the moonlight, but I could see he wasn’t breathing.

“Is he dead?” I asked, not wanting to hear the answer.

Father didn’t reply. He turned Josiah over, picked him up, held him upside down with one hand, and began pumping his stomach hard with the other.

Nothing happened.

Father continued pumping.

After what seemed an eon, Josiah coughed, and sea water poured out of his mouth. Then he began to breathe.

Father laid him down on his back but turned his head so any sea water that came out wouldn’t go back down his throat.

Josiah lay there, not moving, his eyes closed.

After a long wait, he began to open his eyes. He looked up at me and Father and then at the sky.

“Why?” he asked, feebly.

“Why what?” I replied, kneeling beside him.

“Why did you save me? Why didn’t you just let me end it the way I wanted to? If you’d just left me alone, I’d be with Father and Mother now. I wouldn’t be sad any longer.”

“Josiah,” I said, “Your father and the other crew members gave their lives so you could live. Would drowning yourself be thanking them? They wanted you to live, Josiah. Your father wanted you to live. Don’t throw their sacrifice away.”

He looked at me, and I could see that tears were mingling with the sea water on his face. He reached his arms up. Father and I helped him to stand. We supported him as we walked slowly back to the house.

We helped Josiah up the stairs, removed his night gown, gave him a dry one, and told him to get into bed.

I changed my gown and climbed in beside him.

Father hadn’t said a word the whole time since he’d pulled us to shore. Looking down, he said now, “Caleb is right, Josiah. Accidents happen and people die, but occasionally they have a chance to save someone else. Don’t give up that gift.”

He went downstairs quietly, and I tried to snuggle with Josiah and warm him.

“I won’t say thank you,” he said. “But I will say you were very brave. Why do you even care?”

“I would care about anybody who tried to do what you were doing, but I do care more for you. I’d have been heartbroken if you’d died.” I surprised myself when I said that, but after thinking about it, I knew it was true.